Dolores "Lola" Velásquez Cueto | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | María Dolores Velázquez Rivas March 2, 1897 Azcapotzalco, Mexico |

| Died | January 24, 1978 (aged 80) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Other names | María Dolores Velázquez Rivas de Cueto, Lola Velázquez Cueto |

| Education | Academy of San Carlos |

| Known for | painting, printmaking, puppet design |

| Spouse | Germán Cueto |

| Children | 2, including Mireya Cueto |

María Dolores Velázquez Rivas, better known as "Lola" Cueto (Azcapotzalco, March 2, 1897 – Mexico City, January 24, 1978) was a Mexican painter, printmaker, puppet designer and puppeteer. She is best known for her work in children's theater, creating sets, puppets and theatre companies performing pieces for educational purposes. Cueto took her last name from husband Germán Cueto, which whom she had two daughters, one of whom is noted playwright and puppeteer Mireya Cueto. Most of Cueto's artistic interest was related to Mexican handcrafts and folk art, either creating paintings about it or creating traditional works such as tapestries, papel picado and traditional Mexican toys.

Life

Cueto was born María Dolores Velázquez Rivas in Azcapotzalco (now part of Mexico City) on March 2, 1897, to Juan Velázquez and Ana María Rivas.[1][2]

Cueto entered the Academy of San Carlos when she was 12 years old. She was one of the academy's first female students, breaking social norms for women at the time.[3] She was part of a group of students that included David Alfaro Siqueiros and Andrés Audifred, which rebelled against the traditional teaching methods of the academy. It is believed that she was the first female student there to be allowed into classes drawing nudes.[2] Her studies at San Carlos were interrupted by the Mexican Revolution and later she entered the Escuela de Pintura al Aire Libre, also known as the Escuela de Barbizón created and directed by Alfredo Ramos Martínez.[1][2]

In 1919, she married vanguard sculptor Germán Cueto. The couple was prominent in the artistic and intellectual circles of Mexico City which included Diego Rivera, Lupe Marín, Ramón Alva de la Canal, Fermín Revueltas, Germán List Arzubide, Manuel Maples Arce and Arqueles Vela.[2] It was as this time she assumed her husband's last name as her own (not common practice in Mexico), becoming best known as Lola (diminutive for Dolores) Cueto.[1][2]

From 1927 to 1932, she lived with her husband in Paris, where both experienced critical moments in their artistic development.[2] While living in Paris, they had their first contact with puppetry and hand puppet design. Upon their return to Mexico, they founded a glove puppet theatre named "Rin-Rin."[4] With the support of the Ministry of Public Education, several groups were formed to perform the Cuetos' puppet shows in schools throughout Mexico, over a period of fifty years.[4] In 1936 the couple separated.[5] Lola and Gérman Cueto had two daughters, named Ana Maria and Mireya (b. 1922), who became a well-known puppeteer, writer and playwright, winning the Bellas Artes Medal for her life's work.[6] Mireya began her career helping her parents.[7]

Lola Cueto died on January 24, 1978, in Mexico City.[1]

Career

Lola Cueto was one a few working women artists in Mexico in the early twentieth century, at a time when the field was dominated by men.[8] Her contemporaries include María Izquierdo, Olga Costa and Helen Escobedo. Mexico City was a hub for art movements and collaborations in the 1920s. Among these were Stridentism, a popular multidisciplinary avant-garde movement. Although mostly male-dominated, a few women did manage to gain a foothold. One of then was Cueto herself, armed with a sewing machine. While her husband worked within the movement as a sculptor, she brought modernity to the art of tapestries by using her sewing machine. Her almost Pre-Columbian style was merged with folk depictions, all made possible with the use of a Cornelli embroidery machine.[9]

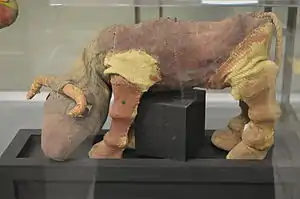

She is best known for her work in theatre, especially with puppets and marionettes for children. Germán had the idea to create marionettes and puppets when the couple lived in Paris, but it was Lola who pursued it.[7] Most of her theatre work was related to education.[10] She founded the Rin Run, El Nahual and El Colorín theatre companies which performed educational sketches in urban and rural areas.[1] One of her major theatrical works was with Silvestre Revueltas from between 1933 and 1935, with a marionette ballet called “El Renacuajo Paseador.” It was presented at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in 1940.[8]

While she lived in Paris beginning in 1926, Lola Cueto began to see her work receive praise unlike any she'd seen for her paintings. The French, in particular, featured her prominently as one of the faces of the Mexican Renaissance within the L' Art Vivant journal in 1928. It was common knowledge both in France and among other Mexican artists that Cueto's tapestry work was exceptional and entrancing. And as it was in a 'timeless medium,' it reached more people than the high and mighty paintings and sculptures of fine artists ever would.[9]

In addition to puppets and marionettes, she had a strong interest in Mexican handcrafts and folk art, which influenced her art. Her earliest work in the early 1920s was the design and crafting of tapestry while she lived in Paris. The work received recognition at exhibitions in Paris, Barcelona and Rotterdam.[2]

Following the reforms and revolutions taking place in Mexican art and thought, List Arzubide and Leopoldo Mendez form ''Troka'' in 1932 to involve the teaching of other more varied art forms to children within educational institutions. They call each other friends they had made in France for their unique specialties to help form the group. Cueto was invited, and funding for her puppetry was provided.[11]

She created an early abstract sculpture.[1] José Luis Cuevas called her the first artist in Mexico to discover abstract art.[8]

At the end of the 1930s, she joined the Sociedad Mexicana de Grabadores and worked under Carlos Alvarado Lang. Her best work here was in mezzotint which stands out with its play on light and shadow.[2] She created the aquatints for a 1947 book by Roberto Lago called “Títeres Populares Mexicanos” (Folk Mexican Puppets).[8] Roberto Lago featured Cueto's puppetry in his 1941 book "Mexican Folk Puppets." She also contributed greatly to the book's illustrations, using a small yet vivid color pallette to depict popular and indigenous Mexican culture.[12]

She gave classes at Mexico City College. Her students included José Luis Cuevas.[1]

She was a founding member of the Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios, founded in her home.[10][13]

Unlike other artists of the era, particularly her female contemporaries like Frida Khaldo, she didn't generate much controversy nor, consequently, much criticism for her work. By embracing the traditional and gendered, she sacrificed conventional creativity. Yet she found expression though parody. Through figurines in puppetry and paper mache of cathedrals, rosaries, and other religious iconography, she poses social commentary on the complexity of things like faith and where it fits in an increasingly secular Mexico.[14]

She did not have many exhibitions of her work, but it was extensively written about by critics Paul Westheim and artist Jean Charlot.[6] Charlot was impressed by her work after dropping in on a chance visit, back when Cueto rented an apartment out to Diego Rivera right next door. She described the panels of embroidery to be both individual and discrete... and also distinctly Mexican.[15] There was an individual exhibition of her work shortly after her death at the Salón de la Plástica Mexicana. Thirty years after that, in 2009, there was a retrospective of her work sponsored by the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes.[3]

Artistry

Cueto is best known for her work in children's theatre, especially that aimed at basic literacy. Her career also included weaving, watercolors, drawings, graphic work, oils, gouache, along with the design of marionettes, puppets, theatre sets and traditional Mexican toys.[3][16] (trancendencia) She is recognized as a master and innovator in the creation of marionettes and children's theatre.[10]

Her early paintings are rigid, generally Impressionist style landscapes.[2] Her later visual work is focused on Mexican handcrafts and folk art both in imagery and handcraft techniques incorporated into them. A mark of the times was modern art and popular folk art. The fact that Cueto opted to focus on handcrafts was the true surprise.[14] One example are paintings of traditional Mexican toys, inspired by her concern of the rise of mass-produced toys in Mexico.[1][6]

Although she is not considered to be an artisan, she did work with a number of traditional crafts such as lacquer, papel picado designs, embroidery and the making of traditional toys and marionettes for theatre performances.[1][10]

Her notable creations include tapestries and other fabrics that have been machine embroidered. These include a series inspired by the stained glass windows of the Gothic cathedrals in Chartres and Bourges. She created a number of tapestries with religious themes such as primitive Christ and Virgin Mary images, rural altars as well as depicting indigenous people.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Tesoros del Registro Civil Salón de la Plástica Mexicana [Treasures of the Civil Registry Salón de la Plástica Mexicana] (in Spanish). Mexico: Government of Mexico City and CONACULTA. 2012. p. 62.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Gómez Haro, Germaine (August 2, 2009). "Lola Cueto en el Museo Mural Diego Rivera (I de II)" [Lola Cueto at the Diego Rivera Mural Museum]. La Jornada Semanal (in Spanish). Mexico City. 752. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Leticia Sánchez (April 13, 2009). "Rescatan del olvido a Lola Cueto" [Rescue Lola Cueta from oblivian]. Milenio (in Spanish). Mexico City. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- 1 2 "Cueto family". World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts. 2016-04-19. Retrieved 2020-02-29.

- ↑ Germán Cueto: la memoria como vanguardia. San Luis Potosí: Museo Federico Silva, 2006.

- 1 2 3 Oscar Cid de León (April 18, 2009). "Hacen justicia a Lola Cueto" [Do justice to Lola Cueto]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 18.

- 1 2 Julieta Riveroll (February 16, 2012). "Hacía títeres para ayudar a mis padres" [I used to make puppets to help my parents]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 19.

- 1 2 3 4 Rodrigo Ledesma Gómez (February 9, 2008). "Ellas rompen esquemas" [They break boundaries]. El Norte (in Spanish). Monterrey. p. 6.

- 1 2 Flores, Tatiana (2008). "Strategic Modernists: Women Artists in Post-Revolutionary Mexico". Woman's Art Journal. 29 (2): 12–22. ISSN 0270-7993. JSTOR 20358161.

- 1 2 3 4 ÁNGEL VARGAS (July 19, 2009). "Presentan catálogo de Lola Cueto: trascendencia mágica en el Museo Mural Diego Rivera" [Present Lola Cueto catalog: Trascendencia mágica at the Diego Rivera Mural Museum]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ Townsend, Sarah Jo (2015-09-01). "Radio/puppets; Or, the institutionalization of a (media) revolution and the afterlife of a mexican avant-garde". Cultural Critique. 91: 32–71. doi:10.5749/culturalcritique.91.2015.0032. ISSN 0882-4371.

- ↑ Vargas, George (1988). Contemporary Latino art in Michigan, the Midwest, and the Southwest (Thesis). hdl:2027.42/128292.

- ↑ ""Trascendencia mágica (1897-1978)", de Lola Cueto". Proceso (in Spanish). Mexico City. May 11, 2009. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- 1 2 Berdeja, Juan M. (2018-08-08). "El ojo microscópico: la relevancia de lo nimio y lo mínimo en el arte narrativo, pictórico y guiñol posrevolucionario". Cuadernos de Literatura (in Spanish). 22 (43). doi:10.11144/Javeriana.cl22-43.omrn. ISSN 2346-1691.

- ↑ Glusker, Susannah Joel; Brenner, Anita (1998-06-05). Anita Brenner A Mind of Her Own By Susannah Joel Glusker. ISBN 978-0-292-72810-3.

- ↑ "Buscan recuperar la vasta y polifacética producción artística de Lola Cueto" [Seek to recuperate the vasta and polyfaceted artistic production of Lola Cueto]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. April 25, 2009. p. 6. Retrieved September 20, 2012.