_-_James_Tissot.jpg.webp)

The Lord's Prayer, often known by its incipit Our Father (Greek: Πάτερ ἡμῶν, Latin: Pater Noster), is a central Christian prayer which Jesus taught as the way to pray. Two versions of this prayer are recorded in the gospels: a longer form within the Sermon on the Mount in the Gospel of Matthew, and a shorter form in the Gospel of Luke when "one of his disciples said to him, 'Lord, teach us to pray, as John taught his disciples'".[1] Regarding the presence of the two versions, some have suggested that both were original, the Matthean version spoken by Jesus early in his ministry in Galilee, and the Lucan version one year later, "very likely in Judea".[2]

Didache (at chapter VIII) reports a version which is closely similar to that of Matthew and also to the modern prayer. It ends with the Minor Doxology.[3]

The first three of the seven petitions in Matthew address God; the other four are related to human needs and concerns. Matthew's account alone includes the "Your will be done" and the "Rescue us from the evil one" (or "Deliver us from evil") petitions. Both original Greek texts contain the adjective epiousion; while controversial, "daily" has been the most common English-language translation of this word.

Initial words on the topic from the Catechism of the Catholic Church teach that it "is truly the summary of the whole gospel".[4] The prayer is used by most Christian denominations in their worship and with few exceptions, the liturgical form is the version from the gospel of Matthew. Protestants usually conclude the prayer with a doxology (in some versions, "For thine is the kingdom, the power and the glory, for ever and ever, Amen"), a later addition appearing in some manuscripts of Matthew. Although theological differences and various modes of worship divide Christians, according to Fuller Seminary professor Clayton Schmit, "there is a sense of solidarity in knowing that Christians around the globe are praying together ... and these words always unite us."[5]

Texts

New International Version

| Matthew 6:9–13 (NIV)[6] | Luke 11:2–4 (NIV)[7] |

|---|---|

| Our Father in heaven, | Father, [Some manuscripts Our Father in heaven] |

| hallowed be your name, | hallowed be your name, |

| your kingdom come, | your kingdom come. |

| your will be done,

on earth as it is in heaven. |

[Some manuscripts come. May your will be done on earth as it is in heaven.] |

| Give us today our daily bread. | Give us each day our daily bread. |

| And forgive us our debts,

as we also have forgiven our debtors. |

Forgive us our sins,

for we also forgive everyone who sins against us. [Greek everyone who is indebted to us] |

| And lead us not into temptation, [The Greek for temptation can also mean testing.]

but deliver us from the evil one. [Or from evil] |

And lead us not into temptation. [Some manuscripts temptation, but deliver us from the evil one] |

| [some late manuscripts one, / for yours is the kingdom and the power and the glory forever. Amen.] |

Relationship between the Matthaean and Lucan texts

In biblical criticism, the absence of the Lord's Prayer in the Gospel of Mark, together with its occurrence in Matthew and Luke, has caused scholars who accept the two-source hypothesis (against other document hypotheses) to conclude that it is probably a logion original to the Q source.[8] The common source of the two existing versions, whether Q or an oral or another written tradition, was elaborated differently in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke.

Marianus Pale Hera considers it unlikely that either of the two used the other as its source and that it is possible that they "preserve two versions of the Lord’s Prayer used in two different communities: the Matthean in a Jewish Christian community and the Lucan in the Gentile Christian community".[9]

If either evangelist built on the other, Joachim Jeremias attributes priority to Luke on the grounds that "in the early period, before wordings were fixed, liturgical texts were elaborated, expanded and enriched".[10] On the other hand, Michael Goulder, Thomas J. Mosbo and Ken Olson see the shorter Lucan version as a reworking of the Matthaean text, removing unnecessary verbiage and repetition.[11]

The Matthaean version has completely ousted the Lucan in general Christian usage,[12] The following considerations are based on the Matthaean version.

Original Greek text and Syriac and Latin translations

|

Standard edition of Greek text[lower-alpha 1] 1. πάτερ ἡμῶν ὁ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς 2. ἁγιασθήτω τὸ ὄνομά σου 3. ἐλθέτω ἡ βασιλεία σου 4. γενηθήτω τὸ θέλημά σου ὡς ἐν οὐρανῷ καὶ ἐπὶ γῆς 5. τὸν ἄρτον ἡμῶν τὸν ἐπιούσιον δὸς ἡμῖν σήμερον 6. καὶ ἄφες ἡμῖν τὰ ὀφειλήματα ἡμῶν ὡς καὶ ἡμεῖς ἀφήκαμεν τοῖς ὀφειλέταις ἡμῶν 7. καὶ μὴ εἰσενέγκῃς ἡμᾶς εἰς πειρασμόν ἀλλὰ ῥῦσαι ἡμᾶς ἀπὸ τοῦ πονηροῦ |

|

|

Liturgical texts: Greek, Syriac, Latin

|

Patriarchal Edition 1904[lower-alpha 7] Πάτερ ἡμῶν ὁ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς, |

|

Roman Missal[15][lower-alpha 13]

|

Greek texts

| Liturgical text | Codex Vaticanus text | Didache text[16] |

|---|---|---|

| πάτερ ἡμῶν ὁ ἐν τοῖς οὐρανοῖς | πατερ ημων ο εν τοις ουρανοις | πατερ ημων ο εν τω ουρανω |

| ἁγιασθήτω τὸ ὄνομά σου | αγιασθητω το ονομα σου | αγιασθητω το ονομα σου |

| ἐλθέτω ἡ βασιλεία σου | ελθετω η βασιλεια σου | ελθετω η βασιλεια σου |

| γενηθήτω τὸ θέλημά σου ὡς ἐν οὐρανῷ καὶ ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς | γενηθητω το θελημα σου ως εν ουρανω και επι γης | γενηθητω το θελημα σου ως εν ουρανω και επι γης |

| τὸν ἄρτον ἡμῶν τὸν ἐπιούσιον δὸς ἡμῖν σήμερον | τον αρτον ημων τον επιουσιον δος ημιν σημερον | τον αρτον ημων τον επιουσιον δος ημιν σημερον |

| καὶ ἄφες ἡμῖν τὰ ὀφειλήματα ἡμῶν ὡς καὶ ἡμεῖς ἀφίεμεν τοῖς ὀφειλέταις ἡμῶν | και αφες ημιν τα οφειληματα ημων ως και ημεις αφηκαμεν τοις οφειλεταις ημων | και αφες ημιν την οφειλην ημων ως και ημεις αφιεμεν τοις οφειλεταις ημων |

| καὶ μὴ εἰσενέγκῃς ἡμᾶς εἰς πειρασμόν ἀλλὰ ῥῦσαι ἡμᾶς ἀπὸ τοῦ πονηροῦ | και μη εισενεγκης ημας εις πειρασμον αλλα ρυσαι ημας απο του πονηρου | και μη εισενεγκης ημας εις πειρασμον αλλα ρυσαι ημας απο του πονηρου |

English versions

.jpg.webp)

There are several different English translations of the Lord's Prayer from Greek or Latin, beginning around AD 650 with the Northumbrian translation. Of those in current liturgical use, the three best-known are:

- The translation in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England

- The slightly modernized "traditional ecumenical" form used in the Catholic[17] and (often with doxology) many Protestant Churches[18]

- The 1988 translation of the ecumenical English Language Liturgical Consultation (ELLC)

The concluding doxology ("For thine is the kingdom and the power, and the glory, for ever and ever. Amen") is often added at the end of the prayer by Protestants. The 1662 Book of Common Prayer (BCP) adds doxology in some of the services, but not in all. For example, the doxology is not used in the 1662 BCP at Morning and Evening Prayer when it is preceded by the Kyrie eleison. Older English translations of the Bible, based on late Byzantine Greek manuscripts, included it, but it is excluded in critical editions of the New Testament, such as that of the United Bible Societies. It is absent in the oldest manuscripts and is not considered to be part of the original text of Matthew 6:9–13.

In the Byzantine Rite, whenever a priest is officiating, after the Lord's Prayer he intones this augmented form of the doxology, "For thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory: of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, now and ever, and unto ages of ages.",[lower-alpha 15] and in either instance, reciter(s) of the prayer reply "Amen".

The Catholic Latin liturgical rites have never attached the doxology to the end of the Lord's Prayer. The doxology does appear in the Roman Rite Mass as revised in 1969. After the conclusion of the Lord's Prayer, the priest says a prayer known as the embolism. In the official International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) English translation, the embolism reads: "Deliver us, Lord, we pray, from every evil, graciously grant peace in our days, that, by the help of your mercy, we may be always free from sin and safe from all distress, as we await the blessed hope and the coming of our Saviour, Jesus Christ." This elaborates on the final petition, "Deliver us from evil." The people then respond to this with the doxology: "For the kingdom, the power, and the glory are yours, now and forever."

The translators of the 1611 King James Bible assumed that a Greek manuscript they possessed was ancient and therefore adopted the phrase "For thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory for ever" into the Lord's Prayer of Matthew's Gospel. However, the use of the doxology in English dates from at least 1549 with the First Prayer Book of Edward VI which was influenced by William Tyndale's New Testament translation in 1526. Later scholarship demonstrated that inclusion of the doxology in New Testament manuscripts was actually a later addition based in part on Eastern liturgical tradition.

|

|

|

King James Version

Although Matthew 6:12 uses the term debts, most older English versions of the Lord's Prayer use the term trespasses, while ecumenical versions often use the term sins. The last choice may be due to Luke 11:4,[26] which uses the word sins, while the former may be due to Matthew 6:14 (immediately after the text of the prayer), where Jesus speaks of trespasses. As early as the third century, Origen of Alexandria used the word trespasses (παραπτώματα) in the prayer. Although the Latin form that was traditionally used in Western Europe has debita (debts), most English-speaking Christians (except Scottish Presbyterians and some others of the Dutch Reformed tradition) use trespasses. For example, the Church of Scotland, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), the Reformed Church in America, as well as some Congregational heritage churches in the United Church of Christ follow the version found in Matthew 6 in the King James Version, which in the prayer uses the words debts and debtors.

|

|

All these versions are based on the text in Matthew, rather than Luke, of the prayer given by Jesus:

|

|

Analysis

Saint Augustine of Hippo gives the following analysis of the Lord's Prayer, which elaborates on Jesus' words just before it in Matthew's Gospel: "Your Father knows what you need before you ask him. Pray then in this way" (Mt. 6:8–9):[29]

We need to use words (when we pray) so that we may remind ourselves to consider carefully what we are asking, not so that we may think we can instruct the Lord or prevail on him. When we say: "Hallowed be your name", we are reminding ourselves to desire that his name, which in fact is always holy, should also be considered holy among men. …But this is a help for men, not for God. …And as for our saying: "Your kingdom come," it will surely come whether we will it or not. But we are stirring up our desires for the kingdom so that it can come to us and we can deserve to reign there. …When we say: "Deliver us from evil," we are reminding ourselves to reflect on the fact that we do not yet enjoy the state of blessedness in which we shall suffer no evil. …It was very appropriate that all these truths should be entrusted to us to remember in these very words. Whatever be the other words we may prefer to say (words which the one praying chooses so that his disposition may become clearer to himself or which he simply adopts so that his disposition may be intensified), we say nothing that is not contained in the Lord’s Prayer, provided of course we are praying in a correct and proper way.

This excerpt from Augustine is included in the Office of Readings in the Catholic Liturgy of the Hours.[30]

Many have written biblical commentaries on the Lord's Prayer.[31][32][33][34] Contained below are a variety of selections from some of those commentaries.

Introduction

This subheading and those that follow use 1662 Book of Common Prayer (BCP) (see above)

Our Father, which art in heaven

"Our" indicates that the prayer is that of a group of people who consider themselves children of God and who call God their "Father". "In heaven" indicates that the Father who is addressed is distinct from human fathers on earth.[35]

Augustine interpreted "heaven" (coelum, sky) in this context as meaning "in the hearts of the righteous, as it were in His holy temple".[36]

First Petition

Hallowed be thy Name;

Former archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams explains this phrase as a petition that people may look upon God's name as holy, as something that inspires awe and reverence, and that they may not trivialize it by making God a tool for their purposes, to "put other people down, or as a sort of magic to make themselves feel safe". He sums up the meaning of the phrase by saying: "Understand what you're talking about when you're talking about God, this is serious, this is the most wonderful and frightening reality that we could imagine, more wonderful and frightening than we can imagine."[37]

Richard Challoner writes that: "this petition hold the primary place in the Lord's prayer, because the first and principal duty of a Christian is, to love his God with his whole heart and soul, and therefore the first and principal thing he should desire and pray for is, the great honor and glory of God."[38]

Second Petition

Thy kingdom come;

"This petition has its parallel in the Jewish prayer, 'May he establish his Kingdom during your life and during your days.'"[39] In the gospels Jesus speaks frequently of God's kingdom, but never defines the concept: "He assumed this was a concept so familiar that it did not require definition."[40] Concerning how Jesus' audience in the gospels would have understood him, G. E. Ladd turns to the concept's Hebrew biblical background: "The Hebrew word malkuth […] refers first to a reign, dominion, or rule and only secondarily to the realm over which a reign is exercised. […] When malkuth is used of God, it almost always refers to his authority or to his rule as the heavenly King."[41] This petition looks to the perfect establishment of God's rule in the world in the future, an act of God resulting in the eschatological order of the new age.[42]

The Catholic Church believes that, by praying the Lord's prayer, a Christian hastens the Second Coming.[43] Like the church, some denominations see the coming of God's kingdom as a divine gift to be prayed for, not a human achievement. Others believe that the Kingdom will be fostered by the hands of those faithful who work for a better world. These believe that Jesus' commands to feed the hungry and clothe the needy make the seeds of the kingdom already present on earth (Lk 8:5–15; Mt 25:31–40).

Hilda C. Graef notes that the operative Greek word, basileia, means both kingdom and kingship (i.e., reign, dominion, governing, etc.), but that the English word kingdom loses this double meaning.[44] Kingship adds a psychological meaning to the petition: one is also praying for the condition of soul where one follows God's will.

Richard Challoner, commenting on this petition, notes that the kingdom of God can be understood in three ways: 1) of the eternal kingdom of God in heaven. 2) of the spiritual kingdom of Christ, in his Church upon earth. 3) of the mystical kingdom of God, in our souls, according to the words of Christ, "The kingdom of God is within you" (Luke 17:21).[38]

Third Petition

Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven:

According to William Barclay, this phrase is a couplet with the same meaning as "Thy kingdom come." Barclay argues: "The kingdom is a state of things on earth in which God's will is as perfectly done as it is in heaven. ...To do the will of God and to be in the Kingdom of God are one and the same thing."[45]

John Ortberg interprets this phrase as follows: "Many people think our job is to get my afterlife destination taken care of, then tread water till we all get ejected and God comes back and torches this place. But Jesus never told anybody – neither his disciples nor us – to pray, 'Get me out of here so I can go up there.' His prayer was, 'Make up there come down here.' Make things down here run the way they do up there."[46] The request that "thy will be done" is God's invitation to "join him in making things down here the way they are up there."[46]

Fourth Petition

Give us this day our daily [epiousion] bread;

As mentioned earlier, the original word ἐπιούσιος (epiousion), commonly characterized as daily, is unique to the Lord's Prayer in all of ancient Greek literature. The word is almost a hapax legomenon, occurring only in Luke and Matthew's versions of the Lord's Prayer, and nowhere else in any other extant Greek texts. While epiousion is often substituted by the word "daily," all other New Testament translations from the Greek into "daily" otherwise reference hemeran (ἡμέραν, "the day"), which does not appear in this usage.

Jerome by linguistic parsing translated "ἐπιούσιον" (epiousion) as "supersubstantialem" in the Gospel of Matthew, but as "cotidianum" ("daily") in the Gospel of Luke. This wide-ranging difference with respect to meaning of epiousion is discussed in detail in the current Catechism of the Catholic Church in an inclusive approach toward tradition as well as a literal one for meaning: "Taken in a temporal sense, this word is a pedagogical repetition of 'this day', to confirm us in trust 'without reservation'. Taken in the qualitative sense, it signifies what is necessary for life, and more broadly every good thing sufficient for subsistence. Taken literally (epi-ousios: 'super-essential'), it refers directly to the Bread of Life, the Body of Christ, the 'medicine of immortality,' without which we have no life within us."[47]

Epiousion is translated as supersubstantialem in the Vulgate Matthew 6:11[48] and accordingly as supersubstantial in the Douay–Rheims Bible Matthew 6:11.[49]

Barclay M. Newman's A Concise Greek-English Dictionary of the New Testament, published in a revised edition in 2010 by the United Bible Societies, has the following entry:

ἐπι|ούσιος, ον (εἰμί) of doubtful meaning, for today; for the coming day; necessary for existence.[50]

It thus derives the word from the preposition ἐπί (epi) and the verb εἰμί (eimi), from the latter of which are derived words such as οὐσία (ousia), the range of whose meanings is indicated in A Greek–English Lexicon.[51]

Fifth Petition

And forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us;

The Presbyterian and other Reformed churches tend to use the rendering "forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors". Roman Catholics, Lutherans, Anglicans and Methodists are more likely to say "trespasses… those who trespass against us".[52] The "debts" form appears in the first English translation of the Bible, by John Wycliffe in 1395 (Wycliffe spelling "dettis"). The "trespasses" version appears in the 1526 translation by William Tyndale (Tyndale spelling "treaspases"). In 1549 the first Book of Common Prayer in English used a version of the prayer with "trespasses". This became the "official" version used in Anglican congregations. On the other hand, the 1611 King James Version, the version specifically authorized for the Church of England, has "forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors".

After the request for bread, Matthew and Luke diverge slightly. Matthew continues with a request for debts to be forgiven in the same manner as people have forgiven those who have debts against them. Luke, on the other hand, makes a similar request about sins being forgiven in the manner of debts being forgiven between people. The word "debts" (ὀφειλήματα) does not necessarily mean financial obligations, as shown by the use of the verbal form of the same word (ὀφείλετε) in passages such as Romans 13:8.[53] The Aramaic word ḥôbâ can mean "debt" or "sin".[54][55] This difference between Luke's and Matthew's wording could be explained by the original form of the prayer having been in Aramaic. The generally accepted interpretation is thus that the request is for forgiveness of sin, not of supposed loans granted by God.[56] Asking for forgiveness from God was a staple of Jewish prayers (e.g., Penitential Psalms). It was also considered proper for individuals to be forgiving of others, so the sentiment expressed in the prayer would have been a common one of the time.

Anthony C. Deane, Canon of Worcester Cathedral, suggested that the choice of the word "ὀφειλήματα" (debts), rather than "ἁμαρτίας" (sins), indicates a reference to failures to use opportunities of doing good. He linked this with the parable of the sheep and the goats (also in Matthew's Gospel), in which the grounds for condemnation are not wrongdoing in the ordinary sense, but failure to do right, missing opportunities for showing love to others.[57][58]

"As we forgive ...". Divergence between Matthew's "debts" and Luke's "sins" is relatively trivial compared to the impact of the second half of this statement. The verses immediately following the Lord's Prayer, Matthew 6:14–15[59] show Jesus teaching that the forgiveness of our sin/debt (by God) is linked with how we forgive others, as in the Parable of the Unforgiving Servant Matthew 18:23–35,[60] which Matthew gives later. R. T. France comments:

The point is not so much that forgiving is a prior condition of being forgiven, but that forgiving cannot be a one-way process. Like all God's gifts it brings responsibility; it must be passed on. To ask for forgiveness on any other basis is hypocrisy. There can be no question, of course, of our forgiving being in proportion to what we are forgiven, as 18:23–35 makes clear.[61]

Sixth Petition

And lead us not into temptation,

Interpretations of the penultimate petition of the prayer – not to be led by God into peirasmos – vary considerably. The range of meanings of the Greek word "πειρασμός" (peirasmos) is illustrated in New Testament Greek lexicons.[62] In different contexts it can mean temptation, testing, trial, experiment. Although the traditional English translation uses the word "temptation" and Carl Jung saw God as actually leading people astray,[63] Christians generally interpret the petition as not contradicting James 1:13–14: "Let no one say when he is tempted, 'I am being tempted by God', for God cannot be tempted with evil, and he himself tempts no one. But each person is tempted when he is lured and enticed by his own desire."[64] Some see the petition as an eschatological appeal against unfavourable Last Judgment, a theory supported by the use of the word "peirasmos" in this sense in Revelation 3:10.[65] Others see it as a plea against hard tests described elsewhere in scripture, such as those of Job.[lower-alpha 16] It is also read as: "Do not let us be led (by ourselves, by others, by Satan) into temptations". Since it follows shortly after a plea for daily bread (i.e., material sustenance), it is also seen as referring to not being caught up in the material pleasures given. A similar phrase appears in Matthew 26:41[66] and Luke 22:40[67] in connection with the prayer of Jesus in Gethsemane.[68]

Joseph Smith, the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, in a version of the Holy Bible which was not published before his death, used: "And suffer us not to be led into temptation".[69]

In a conversation on the Italian TV channel TV2000 on 6 December 2017, Pope Francis commented that the then Italian wording of this petition (similar to the traditional English) was a poor translation. He said "the French" (i.e., the Bishops' Conference of France) had changed the petition to "Do not let us fall in/into temptation". He was referring to the 2017 change to a new French version, Et ne nous laisse pas entrer en tentation ("Do not let us enter into temptation"), but spoke of it in terms of the Spanish translation, no nos dejes caer en la tentación ("do not let us fall in/into temptation"), that he was accustomed to recite in Argentina before his election as Pope. He explained: "I am the one who falls; it's not him [God] pushing me into temptation to then see how I have fallen".[70][71][72] Anglican theologian Ian Paul said that such a proposal was "stepping into a theological debate about the nature of evil".[73]

In January 2018, after "in-depth study", the German Bishops' Conference rejected any rewording of their translation of the Lord's Prayer.[74][75]

In November 2018, the Episcopal Conference of Italy adopted a new edition of the Messale Romano, the Italian translation of the Roman Missal. One of the changes made from the older (1983) edition was to render this petition as non abbandonarci alla tentazione ("do not abandon us to temptation").[76][77] This was approved by Pope Francis; however, there are no current plans to make a similar change for the English translation as of 2019.[78] The Italian-speaking Union of Methodist and Waldensian Churches maintains its translation of the petition: non esporci alla tentazione ("do not expose us to temptation").[79]

Seventh Petition

Translations and scholars are divided over whether the final word here refers to "evil" in general or "the evil one" (the devil) in particular. In the original Greek, as well as in the Latin translation, the word could be either of neuter (evil in general) or masculine (the evil one) gender. Matthew's version of the prayer appears in the Sermon on the Mount, in earlier parts of which the term is used to refer to general evil. Later parts of Matthew refer to the devil when discussing similar issues. However, the devil is never referred to as the evil one in any known Aramaic sources. While John Calvin accepted the vagueness of the term's meaning, he considered that there is little real difference between the two interpretations, and that therefore the question is of no real consequence. Similar phrases are found in John 17:15[81] and Thessalonians 3:3.[82][83]

Doxology

For thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory,

For ever and ever. Amen.

Content

The doxology sometimes attached to the prayer in English is similar to a passage in 1 Chronicles 29:11 – "Yours, O LORD, is the greatness and the power and the glory and the victory and the majesty, for all that is in the heavens and in the earth is yours. Yours is the kingdom, O LORD, and you are exalted as head above all."[84][85] It is also similar to the paean to King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon in Daniel 2:37 – "You, O king, the king of kings, to whom the God of heaven has given the kingdom, the power, and the might, and the glory".[86][85][87]

The doxology has been interpreted as connected with the final petition: "Deliver us from evil". The kingdom, the power and the glory are the Father's, not of our antagonist's, who is subject to him to whom Christ will hand over the kingdom after he has destroyed all dominion, authority and power (1 Corinthians 15:24). It makes the prayer end as well as begin with the vision of God in heaven, in the majesty of his name and kingdom and the perfection of his will and purpose.[88][89][90][91]

Origin

The doxology is not included in Luke's version of the Lord's Prayer, nor is it present in the earliest manuscripts (papyrus or parchment) of Matthew,[92] representative of the Alexandrian text, although it is present in the manuscripts representative of the later Byzantine text.[93] Most scholars do not consider it part of the original text of Matthew.[94][95] The Codex Washingtonianus, which adds a doxology (in the familiar text), is of the early fifth or late fourth century.[96][97] New translations generally omit it except as a footnote.[98][99]

The Didache, generally considered a first-century text, has a doxology, "for yours is the power and the glory forever", as a conclusion for the Lord's Prayer (Didache, 8:2).[87][100][101] C. Clifton Black, although regarding the Didache as an "early second century" text, nevertheless considers the doxology it contains to be the "earliest additional ending we can trace".[100] Of a longer version,[lower-alpha 17] Black observes: "Its earliest appearance may have been in Tatian's Diatessaron, a second-century harmony of the four Gospels".[85] The first three editions of the United Bible Societies text cited the Diatessaron for inclusion of the familiar doxology in Matthew 6:13, but in the later editions it cites the Diatessaron for excluding it.[102] The Apostolic Constitutions added "the kingdom" to the beginning of the formula in the Didache, thus establishing the now familiar doxology.[103][104][105]

Varied liturgical use

In the Byzantine Rite, whenever a priest is officiating, after the last line of the prayer he intones the doxology, "For thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory: of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, now and ever, and unto ages of ages.",[lower-alpha 18] and in either instance, reciter(s) of the prayer reply "Amen".

Adding a doxology to the Our Father is not part of the liturgical tradition of the Roman Rite nor does the Latin Vulgate of St. Jerome contain the doxology that appears in late Greek manuscripts. However, it is recited since 1970 in the Roman Rite Order of Mass, not as part of the Lord's Prayer but separately as a response acclamation after the embolism developing the seventh petition in the perspective of the Final Coming of Christ.

In most Anglican editions of the Book of Common Prayer, the Lord's Prayer ends with the doxology unless it is preceded by the Kyrie eleison. This happens at the daily offices of Morning Prayer (Mattins) and Evening Prayer (Evensong) and in a few other offices. [lower-alpha 19]

The vast majority of Protestant churches conclude the Lord's Prayer with the doxology.

Use as a language comparison tool

In the course of Christianization, one of the first texts to be translated between many languages has historically been the Lord's Prayer, long before the full Bible would be translated into the respective languages. Since the 16th century, collections of translations of the prayer have often been used for a quick comparison of languages. The first such collection, with 22 versions, was Mithridates, de differentiis linguarum by Conrad Gessner (1555; the title refers to Mithridates VI of Pontus who according to Pliny the Elder was an exceptional polyglot).

Gessner's idea of collecting translations of the prayer was taken up by authors of the 17th century, including Hieronymus Megiserus (1603) and Georg Pistorius (1621). Thomas Lüdeken in 1680 published an enlarged collection of 83 versions of the prayer,[106] of which three were in fictional philosophical languages. Lüdeken quotes a Barnimus Hagius as his source for the exotic scripts used, while their true (anonymous) author was Andreas Müller. In 1700, Lüdeken's collection was re-edited by B. Mottus as Oratio dominica plus centum linguis versionibus aut characteribus reddita et expressa. This edition was comparatively inferior, but a second, revised edition was published in 1715 by John Chamberlain. This 1715 edition was used by Gottfried Hensel in his Synopsis Universae Philologiae (1741) to compile "geographico-polyglot maps" where the beginning of the prayer was shown in the geographical area where the respective languages were spoken. Johann Ulrich Kraus also published a collection with more than 100 entries.[107]

These collections continued to be improved and expanded well into the 19th century; Johann Christoph Adelung and Johann Severin Vater in 1806–1817 published the prayer in "well-nigh five hundred languages and dialects".[108]

Samples of scripture, including the Lord's Prayer, were published in 52 oriental languages, most of them not previously found in such collections, translated by the brethren of the Serampore Mission and printed at the mission press there in 1818.

Indulgence

History

In the Catholic Church, a rescript of Pope Pius VII and subsequent decree of the Pro-Vicar Cardinal of 18 April 1809 introduced a 300-day indulgence for whom would recite with heart contrite and devoutly, on behalf of a suffering faithful, 3 Our Fathers in memory of the Passion and agony of Jesus and 3 Hail Marys in memory of the pains of the Virgin in the presence of her divine son. Furthermore, for those who have performed this pious practice at least once a day for a month, they granted plenary indulgence, and the remission of all sins on a day of their choice in which they had confessed, communicated and prayed according to the intentions of the Pope at the time. These indulgences "are perpetual" and can be applied to souls in Purgatory.[109]

After the Second Vatican Council

This type of indulgence was suppressed by the Indulgentiarum Doctrina of Pope Paul VI.

In occasion of the 2020-2021 jubilee of Saint Joseph, Pope Francis signed a decree that granted the plenary indulgence to those who shall contemplate the Lord’s Prayer for at least 30 minutes.[110]

Comparisons with other prayer traditions

The book The Comprehensive New Testament, by T.E. Clontz and J. Clontz, points to similarities between elements of the Lord's Prayer and expressions in writings of other religions as diverse as the Dhammapada, the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Golden Verses, and the Egyptian Book of the Dead.[111] It mentions in particular parallels in 1 Chronicles.[112][113]

Rabbi Aron Mendes Chumaceiro says that nearly all the elements of the prayer have counterparts in the Jewish Bible and Deuterocanonical books: the first part in Isaiah 63 ("Look down from heaven and see, from your holy and beautiful habitation… for you are our Father"[114]) and Ezekiel 36 ("I will vindicate the holiness of my great name…")[115] and 38 ("I will show my greatness and my holiness and make myself known in the eyes of many nations…"),[116] the second part in Obadiah 1 ("Saviours shall go up to Mount Zion to rule Mount Esau, and the kingdom shall be the LORD's")[117] and 1 Samuel 3 ("…It is the LORD. Let him do what seems good to him."),[118] the third part in Proverbs 30 ("…feed me with my apportioned bread…"),[119] the fourth part in Sirach 28 ("Forgive your neighbour the wrong he has done, and then your sins will be pardoned when you pray.").[120] "Deliver us from evil" can be compared with Psalm 119 ("…let no iniquity get dominion over me.").[121][122]

Chumaceiro says that, because the idea of God leading a human into temptation contradicts the righteousness and love of God, "Lead us not into temptation" has no counterpart in the Jewish Bible/Christian Old Testament. However, the word "πειρασμός", which is translated as "temptation", can also be translated as "test" or "trial", making evident the attitude of someone's heart, and in the Old Testament God tested Abraham,[123] and told David, "Go, number Israel and Judah," an action that David later acknowledged as sin;[124] and the testing of Job in the Book of Job.

Reuben Bredenhof says that the various petitions of the Lord's Prayer, as well as the doxology attached to it, have a conceptual and thematic background in the Old Testament Book of Psalms.[125]

On the other hand, Andrew Wommack says that the Lord's Prayer "technically speaking… isn't even a true New Testament prayer".[126]

In post-biblical Jewish prayer, especially Kiddushin 81a (Babylonian).[127] "Our Father which art in heaven" (אבינו שבשמים, Avinu shebashamayim) is the beginning of many Hebrew prayers.[128] "Hallowed be thy name" is reflected in the Kaddish. "Lead us not into sin" is echoed in the "morning blessings" of Jewish prayer. A blessing said by some Jewish communities after the evening Shema includes a phrase quite similar to the opening of the Lord's Prayer: "Our God in heaven, hallow thy name, and establish thy kingdom forever, and rule over us for ever and ever. Amen."

Musical settings

Various composers have incorporated the Lord's Prayer into a musical setting for utilization during liturgical services for a variety of religious traditions as well as interfaith ceremonies. Included among them are:

- 9th–10th century: Gregorian chant

- 1565: Robert Stone – The Lord's Prayer[129]

- 1573: Orlandus Lassus – Pater Noster a4

- 1592: John Farmer – The Lord's Prayer

- 1625: Heinrich Schütz – Pater Noster[130]

- 1783: William Billings – "Kittery" (words from Tate and Brady)[131]

- 1854: Josef Rheinberger – Vater Unser

- 1878: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky – Otche Nash (Отче наш; Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, op. 41)

- 1883: Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov – Otche Nash

- 1906: Leoš Janáček – Otče náš

- 1910: Sergei Rachmaninoff – Otche Nash (Отче наш; Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, op. 31)

- 1919: Emil von Reznicek – "Vater Unser im Himmel" (A Choral Fantasy with Mixed Chorus and Organ)

- 1926: Igor Stravinsky – Otche Nash (Church Slavonic), arr. Pater Noster (Latin, c. 1949)[132]

- 1935: Albert Hay Malotte – "The Lord's Prayer"

- 1961: Bernard Rose – Lord's Prayer (as part of Preces and Responses)[133]

- 1973: Arnold Strals – "The Lord's Prayer" (performed by Sister Janet Mead)[134]

- 1975: Mark Alburger – The Lord's Prayer, Op. 5

- 1976: Maurice Duruflé – Notre Père

- 1985: Clive Strutt – XIII Paternoster in the Festal Eucharist in honour of Saint Olaf, King and Martyr

- 1992: John Serry Sr. – The Lord's Prayer for Organ & Chorus[135]

- 1999: Paul Field and Stephen Deal – "The Millennium Prayer" (performed by Cliff Richard)

- 2000: John Tavener – "The Lord's Prayer"[136]

- 2005: Christopher Tin — Baba Yetu

- 2016: Chris M. Allport — The Lord's Prayer

In popular culture

As with other prayers, the Lord's Prayer was used by cooks to time their recipes before the spread of clocks. For example, a step could be "simmer the broth for three Lord's Prayers".[137]

American songwriter and arranger Brian Wilson set the text of the Lord's Prayer to an elaborate close-harmony arrangement loosely based on Malotte's melody. Wilson's group, The Beach Boys, would return to the piece several times throughout their recording career, most notably as the B-side to their 1964 single "Little Saint Nick."[138] The band Yazoo used the prayer interspersed with the lyrics of "In My Room" on the album Upstairs at Eric's.[139]

Beat Generation poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti wrote and performed a "Loud Prayer" parodying the Lord's Prayer, one version of which was featured in the 1978 film The Last Waltz.[140]

In July 2023, Filipino drag queen and former Drag Den contestant Pura Luka Vega drew controversy online for posting a video of themselves dressing up as Jesus Christ and dancing to a punk rock version of Ama Namin, the Filipino version of the Lord's Prayer. The video was also condemned by several Philippine politicians and the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines.[141]

Images

18th-century painting of the Lord's Prayer, on the north side of the chancel of St Mary's Church, Mundon, Essex.

18th-century painting of the Lord's Prayer, on the north side of the chancel of St Mary's Church, Mundon, Essex. The Lord's Prayer, ink and watercolor by John Morgan Coaley, 1889. Library of Congress.

The Lord's Prayer, ink and watercolor by John Morgan Coaley, 1889. Library of Congress. Lord's Prayer fragment from Lindisfarne Gospels, f. 37r, Latin text, translated in Northumbrian dialect of the Old English.

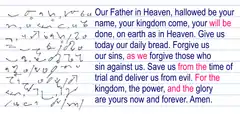

Lord's Prayer fragment from Lindisfarne Gospels, f. 37r, Latin text, translated in Northumbrian dialect of the Old English. The text of the English Language Liturgical Consultation version of the Lord's Prayer, written in Teeline Shorthand and in Latin script for comparison.

The text of the English Language Liturgical Consultation version of the Lord's Prayer, written in Teeline Shorthand and in Latin script for comparison. Lord's Prayer written in Syriac.

Lord's Prayer written in Syriac. Lord's Prayer, three versions from left to right: (1) from Codex Zographensis in Glagolitic script (1100s); (2) from Codex Assemanius in Glagolitic script (1000s); (3) from Gospels of Tsar Ivan Alexander in Bulgarian Cyrillic script (1355).

Lord's Prayer, three versions from left to right: (1) from Codex Zographensis in Glagolitic script (1100s); (2) from Codex Assemanius in Glagolitic script (1000s); (3) from Gospels of Tsar Ivan Alexander in Bulgarian Cyrillic script (1355).

See also

- Al-Fatiha

- Amen

- Baba Yetu – Theme song of the video game Civilization IV, Lord's Prayer sung in Swahili

- Church of the Pater Noster on the Mount of Olives, Jerusalem

- Discourse on ostentation, a portion of the Sermon on the Mount

- Five Discourses of Matthew

- Hail Mary

- High Priestly Prayer

- Prayer in the New Testament

- Rosary

- Didache, an early book of rituals which mentions saying the prayer three times daily

- Novum Testamentum Graece, the primary source for most contemporary New Testament translations

- Textus Receptus

- List of New Testament verses not included in modern English translations

Notes

- ↑ The text given here is that of the latest edition of Greek New Testament of the United Bible Societies and in the Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece. Most modern translations use a text similar to this one. Most older translations are based on a Byzantine-type text with ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς in line 5 (verse 10) instead of ἐπὶ γῆς, and ἀφίεμεν in line 8 (verse 12) instead of ἀφήκαμεν, and adding at the end (verse 13) the doxology ὅτι σοῦ ἐστιν ἡ βασιλεία καὶ ἡ δύναμις καὶ ἡ δόξα εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας. ἀμήν.

- ↑ The Classical Syriac vowels here transcribed as "ê", "ā" and "o/ō" have been raised to "i", "o" and "u" respectively in Western Syriac.[13]

- ↑ Three editions of the Vulgate: the Clementine edition of the Vulgate, the Nova Vulgata, and the Stuttgart Vulgate. The Clementine edition varies from the Nova Vulgata in this place only in punctuation and in having "ne nos inducas" in place of "ne inducas nos". The Stuttgart Vulgate has "qui in caelis es" in place of "qui es in caelis"; "veniat" in place of "adveniat"; "dimisimus" in place of "dimittimus"; "temptationem" in place of "tentationem".

- ↑ In the Nova Vulgata, the official Latin Bible of the Catholic Church, the last word is capitalized, indicating that it is a reference to Malus (the Evil One), not to malum (abstract or generic evil).

- ↑ The doxology associated with the Lord's Prayer in Byzantine Greek texts is found in four Vetus Latina manuscripts, only two of which give it in its entirety. The other surviving manuscripts of the Vetus Latina Gospels do not have the doxology. The Vulgate translation also does not include it, thus agreeing with critical editions of the Greek text.

- ↑ In Greek: Ὅτι σοῦ ἐστὶν ἡ βασιλεία καὶ ἡ δύναμις καὶ ἡ δόξα· τοῦ Πατρὸς καὶ τοῦ Υἱοῦ καὶ τοῦ Ἁγίου Πνεύματος· νῦν καὶ ἀεὶ καὶ εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων.

- ↑ The Greek Orthodox Church uses a slightly different Greek version. which can be found in many liturgical texts, e.g., the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom ( Greek Orthodox Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom), as presented in the 1904 text of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and various Greek prayer books and liturgies. This is the Greek version of the Lord's Prayer most widely used for prayer and liturgy today, and is similar to other texts of the Byzantine text-type used in older English Bible translations, with ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς instead of ἐπὶ γῆς on line 5 and ἀφίεμεν instead of ἀφήκαμεν (present rather than aorist tense) in line 8. Whenever a priest is officiating, he replies with this augmented form of the doxology, "For thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory: of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, now and ever, and unto ages of ages.",[lower-alpha 6] and in either instance, reciter(s) of the prayer reply "Amen".

- ↑ Matthew 6:11 and Luke 11:3 Curetonian Gospels used ʾammīnā (ܐܡܝܢܐ) "constant bread" like Vulgata Clementina used quotidianum "daily bread" in Luke 11:3; see Epiousion.

- ↑ Syriac liturgical text adds "and our sins" to some verses in Matthew 6:12 and Luke 11:4.

- ↑ Syriac "deliver" relates with "Passover", thus Passover means "deliverance": Exodus 12:13.

- ↑ "And" is absent in between the words "kingdom, power, glory". The Old Syriac Curetonian Gospel text varies: "for thine is the kingdom and the glory for an age of ages amen".

- ↑ Didache finishes the prayer just with duality of words "for Thine is the Power and the Glory for ages" without any "amen" in the end. Old Syriac text of Curetonian Gospels finishes the prayer also with duality of words "for Thine is the Kingdom and the Glory for age ages. Amen"

- ↑ The version of the Lord's Prayer most familiar to Western European Christians until the Protestant Reformation is that in the Roman Missal, which has had cultural and historical importance for most regions where English is spoken. The text is used in the Roman Rite liturgy (Mass, Liturgy of the Hours, etc.). It differs from the Vulgate in having cotidianum in place of supersubstantial. It does not add the doxology: this is never joined immediately to the Lord's Prayer in the Latin liturgy or the Latin Bible, but it appears, in the form quia tuum est regnum, et potestas, et gloria, in saecula, in the Mass of the Roman Rite, as revised in 1969, separated from the Lord's Prayer by the prayer, Libera nos, quaesumus... (the embolism), which elaborates on the final petition, Libera nos a malo (deliver us from evil). Others have translated the doxology into Latin as quia tuum est regnum; et potential et Gloria; per Omnia saecula or in saecula saeculorum.

- ↑ In editions of the Roman Missal prior to that of 1962 (the edition of Pope John XXIII) the word cotidianum was spelled quotidianum.

- ↑ In Greek: Ὅτι σοῦ ἐστὶν ἡ βασιλεία καὶ ἡ δύναμις καὶ ἡ δόξα· τοῦ Πατρὸς καὶ τοῦ Υἱοῦ καὶ τοῦ Ἁγίου Πνεύματος· νῦν καὶ ἀεὶ καὶ εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων.

- ↑ Psalm 26:2 and Psalm 139:23 are respectful challenges for a test to prove the writer's innocence and integrity.

- ↑ "For yours is the kingdom and the power and the glory unto the ages. Amen. (AT) [emphasis in original]"[85]

- ↑ In Greek: Ὅτι σοῦ ἐστὶν ἡ βασιλεία καὶ ἡ δύναμις καὶ ἡ δόξα· τοῦ Πατρὸς καὶ τοῦ Υἱοῦ καὶ τοῦ Ἁγίου Πνεύματος· νῦν καὶ ἀεὶ καὶ εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων.

- ↑ For instance, in Morning Prayer the doxology is included in the Lord's Prayer in the Introduction, but not in the Prayers after the Apostles' Creed because it is preceded by the Kyrie eleison.

References

Citations

- ↑ Luke 11:1 NRSV

- ↑ Buls, H. H., The Sermon Notes of Harold Buls: Easter V, accessed 15 June 2018

- ↑ See Ante-Nicene Fathers/Volume VII/The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles/The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles/Chapter VIII

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – The summary of the whole Gospel". Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ Kang, K. Connie. "Across the globe, Christians are united by Lord's Prayer", Los Angeles Times, in Houston Chronicle, p. A13, April 8, 2007.

- ↑ Matthew 6:9–13

- ↑ Luke 11:2–4

- ↑ Farmer, William R., The Gospel of Jesus: The Pastoral Relevance of the Synoptic Problem, Westminster John Knox Press (1994), p. 49, ISBN 978-0-664-25514-5

- ↑ Marianus Pale Hera, "The Lucan Lord's Prayer" in Journal of the Nanzan Academic Society Humanities and Natural Sciences, 17 (January 2019), p. 80―81

- ↑ Joachim Jeremias, The Lord's Prayer, chapter 2: The Earliest Text of the Lord's Prayer

- ↑ Ken Olson, "Luke 11: 2–4: The Lord's Prayer (Abridged Edition)" in Marcan Priority Without Q: Explorations in the Farrer Hypothesis. Bloomsbury Publishing; 26 February 2015. ISBN 978-0-567-36756-3. 5. p. 101–118.

- ↑ Leaney, Robert (1956). "The Lucan Text of the Lord's Prayer (Lk XI 2-4)". Novum Testamentum. 1 (2): 104. doi:10.2307/1560061. JSTOR 1560061.

- ↑ Muraoka, Takamitsu (2005). Classical Syriac: A Basic Grammar with a Chrestomathy. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 6–8. ISBN 3-447-05021-7.

- 1 2 Isaiah 45:7

- ↑ 2002 edition; 1962 edition, pp. 312–313

- ↑ Didache 8

- ↑ , Francis Xavier Weninger. A Manual of the Catholic Religion, for Catechists, Teachers, and Self-instruction. John P. Walsh; 1867. p. 146–147.

- ↑ 1928 version of the Prayer Book of the Episcopal Church (United States)

- ↑ "The Order for Morning Prayer". The Church of England's website. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ↑ USCCB. Order of the Mass (PDF).

- ↑ US Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2010

- ↑ "The Lord's Prayer".

- ↑ "Lord's Prayer". Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ Praying Together

- ↑ Also, cf. 1979 Book of Common Prayer of the United States Episcopal Church Holy Eucharist: Rite Two.

- ↑ Luke 11:4

- ↑ esv Matthew 6:9–13

- ↑ esv Luke 11:2–4

- ↑ "From a letter to Proba by Saint Augustine, bishop (Ep. 130, 11, 21-12, 22: CSEL 44, 63-64) On the Lord's Prayer". Adoratio Iesu Christi. 20 October 2015. Archived from the original on 18 July 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ↑ "Week 29 Tuesday - Office of Readings". www.liturgies.net. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ↑ "Tertullian on the Our Father - Patristic Bible Commentary". sites.google.com. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ↑ Wesley, John. "Commentary on the Lord's Prayer". CS Lewis Institute.

- ↑ "Verses 9–15 - Matthew Henry's Commentary - Bible Gateway". www.biblegateway.com. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ↑ "Matthew 6:9 Commentaries: "Pray, then, in this way: 'Our Father who is in heaven, Hallowed be Your name". biblehub.com. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ↑ Hahn, Scott (2002). Understanding "Our Father": Biblical Reflections on the Lord's Prayer. Steubenville, OH: Emmaus Road Publishing. ISBN 978-1-93101815-9.

- ↑ Augustine, On the Sermon on the Mount, Book II, Chapter 5, 17–18; original text

- ↑ "Religions - Christianity: The Lord's Prayer". BBC. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- 1 2 Challoner, Richard (1915). . The Lord's prayer and the Angelic salutation. SS. Peter and Paul.

- ↑ G. Dalman, The Words of Jesus (1909), 99. As cited in G. E. Ladd, The Presence of the Future (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1974), 137

- ↑ George Eldon Ladd, The Presence of the Future: The Eschatology of Biblical Realism, Eerdmans (Grand Rapids: 1974), 45.

- ↑ George Eldon Ladd, The Presence of the Future: The Eschatology of Biblical Realism, Eerdmans (Grand Rapids: 1974), 46–47.

- ↑ G. E. Ladd, The Presence of the Future (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1974), 136–37

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church 671".

- ↑ Hilda C. Graef, St. Gregory of Nyssa: The Lord's Prayer and the Beatitudes (Ancient Christin Writers, No. 18), Paulist Press (New York: 1954), n. 68, p. 187.

- ↑ Barclay, William (28 January 1976). The Mind of Jesus. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06060451-6.

- 1 2 Ortberg, John Ortberg. "God is Closer Than You Think". Zondervan, 2005, p. 176.

- ↑ "The seven petitions". Catechism of the Catholic Church. Archived from the original on 16 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ↑ Matthew 6:11

- ↑ Matthew 6:11

- ↑ Cf. Barclay M. Newman, A Concise Greek-English Dictionary of the New Testament, Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, United Bible Societies 2010 ISBN 978-3-438-06019-8. Partial preview.

- ↑ "Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, οὐσί-α". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ↑ Chaignot, Mary Jane. Questions and Answers. Archived 2013-01-22 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 11 Feb 2013

- ↑ Romans 13:8

- ↑ Nathan Eubank 2013, Wages of Cross-Bearing and Debt of Sin (Walter de Gruyter ISBN 978-31-1030407-7), p. 2

- ↑ John S. Kloppenborg 2008, Q, the Earliest Gospel (Westminster John Knox Press ISBN 978-1-61164058-8), p. 58.

- ↑ Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, Kittel & Friedrich eds., abridged in one volume by Geoffrey W. Bromiley (Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, Mich; 1985), pp. 746–50, gives use of ὸφείλω opheilo (to owe, be under obligation), ὸφειλή opheile (debt, obligation) and two other word forms used in the New Testament and outside the New Testament, including use in Judaism.

- ↑ Matt. 25:31–46

- ↑ Deane, Anthony C. (1926). "VI. Forgiveness". Our Father: A Study of the Lord's Prayer. Archived from the original on 3 December 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Matt. 6:14–15

- ↑ Matt. 18:23–35

- ↑ France, R. T. (1985). The Gospel According to Matthew: An Introduction and Commentary. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-0063-3.

- ↑ "Entry for Strong's #3986: πειρασμός". Study Light.

- ↑ Jung, Carl, "Answer to Job"

- ↑ James 1:13–14

- ↑ Revelation 3:10

- ↑ Matthew 26:41

- ↑ Luke 22:40

- ↑ Clontz & Clontz 2008, pp. 451–52.

- ↑ JST Matthew 6:14

- ↑ Padre Nostro - Settima puntata: 'Non ci indurre in tentazione' at 1:05.

- ↑ "Pope Francis suggests translation change to the 'Our Father'". America. 8 December 2017. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ↑ Sandro Magister, 'Pater Noster, No Peace. The Battle Begins Among the Translations' Archived 7 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine (7 March 2018).

- ↑ Sherwood, Harriet (8 December 2017). "Lead us not into mistranslation: pope wants Lord's Prayer changed". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ Hannah Brockhaus, "Holy See confirms changes to Italian liturgical translation of Our Father, Gloria" (Catholic News Agency, 7 June 2019).

- ↑ Daly, Greg (26 January 2018). "German hierarchy resists temptation to change Our Father translation". Irish Catholic. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ Pope Francis approves changes to the Lord's prayer, 3 June 2019.

- ↑ "Francis approves revised translation of Italian Missal". international.la-croix.com. 31 May 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ↑ "Holy See confirms changes to Italian liturgical translation of Our Father, Gloria".

- ↑ Innario cristiano (Torino: Claudiana), p. 18

- ↑ Exodus 12:13

- ↑ John 17:15

- ↑ 2 Thessalonians 3:3

- ↑ Clontz & Clontz 2008, p. 452.

- ↑ 1 Chronicles

- 1 2 3 4 Black 2018, p. 228.

- ↑ Daniel

- 1 2 Taylor 1994, p. 69.

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2855

- ↑ Charles Hope Robertson (1858). Gathered lights; illustrating the meaning and structure of the Lord's prayer. pp. 214–219.

- ↑ Robert M. Solomon (2009). The Prayer of Jesus. Armour Publishing Pte Ltd. p. 250. ISBN 978-981-4270-10-6.

- ↑ William Denton (1864). A Commentary Practical and Exegetical on the Lord's Prayer. Rivingtons. pp. 172–178.

- ↑ Nicholas Ayo (1993), The Lord's Prayer: A Survey Theological and Literary, University of Notre Dame Press, p. 7, ISBN 978-0-268-01292-2

- ↑ Clontz & Clontz 2008, p. 8.

- ↑ David E. Aune 2010, The Blackwell Companion to the New Testament (Blackwell ISBN 978-1-4051-0825-6), p. 299.

- ↑ Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland 1998, The Text of the New Testament (Eerdmans ISBN 0-8028-4098-1), p. 306.

- ↑ Joseph M. Holden; Norman Geisler (1 August 2013). The Popular Handbook of Archaeology and the Bible: Discoveries That Confirm the Reliability of Scripture. Harvest House Publishers. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-7369-4485-4.

- ↑ Larry W. Hurtado (2006). The Freer Biblical Manuscripts: Fresh Studies of an American Treasure Trove. Society of Biblical Lit. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-58983-208-4.

- ↑ Michael J. Gorman (1 September 2005). Scripture: An Ecumenical Introduction to the Bible and Its Interpretation. Baker Publishing Group. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-4412-4165-8.

- ↑ David S. Dockery; David E. Garland (10 December 2004). Seeking the Kingdom: The Sermon on the Mount Made Practical for Today. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-59752-009-6.

- 1 2 Black 2018, p. 227.

- ↑ Richardson 1953, p. 174.

- ↑ Matthew R. Crawford; Nicholas J. Zola (11 July 2019). The Gospel of Tatian: Exploring the Nature and Text of the Diatessaron. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-567-67989-5.

- ↑ Alexander Roberts; Sir James Donaldson (1870). Ante-Nicene Christian Library: The Clementine homilies. The Apostolic constitutions (1870). T. and T. Clark. p. 105.

- ↑ Apostolic Constitutions, 7, 24, 1: PG 1,1016

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2760

- ↑ Orationis dominicae versiones praeter authenticam fere centum..., Thomas Lüdeken, Officina Rungiana, 1680.

- ↑ Augustin Backer, Alois Backer, Bibliothèque des écrivains de la compagnie de Jésus ou notices bibliographiques, vol. 5, 1839, 304f.

- ↑ Mithridates oder allgemeine Sprachenkunde mit dem Vater Unser als Sprachprobe in bey nahe fünf hundert Sprachen und Mundarten, 1806–1817, Berlin, Vossische Buchlandlung, 4 volumes. Facsimile edition, Hildesheim-Nueva York, Georg Olms Verlag, 1970.

- ↑ Giovanni Sacchetto (1837). Collection of prayers and pious works for which the Supreme Pontiffs granted the s . indulgences. p. 321.

- ↑ "Decree".

- ↑ Clontz & Clontz 2008.

- ↑ 1 Chronicles 29:10–18

- ↑ Clontz & Clontz 2008, pp. 8, 451.

- ↑ Isaiah 63:15–16

- ↑ Ezekiel 36:23

- ↑ Ezekiel 38:23

- ↑ Obadiah 1:21

- ↑ 1 Samuel 3:18

- ↑ Proverbs 30:8

- ↑ Sirach 28:2

- ↑ Psalm 119:133

- ↑ Verdediging is geen aanval, pp. 121–22

- ↑ Genesis 22:1

- ↑ 2 Samuel 24:1–10; 1 Chronicles 21:1–7

- ↑ Reuben Bredenhof 2019, Hallowed: Echoes of the Psalms in the Lord’s Prayer Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock.

- ↑ Andrew Wommack, 21 March 2007. A Better Way to Pray. Harrison House Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60683-074-1. Chapter 4: Our Father…

- ↑ Clontz & Clontz 2008, p. 451.

- ↑ Stern, David H. (1992). Jewish New Testament Commentary. Jewish New Testament Publications. p. 32. ISBN 978-965359011-3.

- ↑ "The Lord's Prayer (Stone) - from COLCD113 - Hyperion Records - MP3 and Lossless downloads". www.hyperion-records.co.uk. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ↑ "Pater noster, qui es in coelis, SWV 89 (Heinrich Schütz) - ChoralWiki". www.cpdl.org. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ↑ "Kittery (William Billings) - ChoralWiki". www.cpdl.org. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ↑ "Igor Stravinsky - Pater Noster SATB". www.boosey.com. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ↑ "Bernard Rose: Preces And Responses : SATB". www.musicroom.com. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ↑ "The Lord's prayer [music] / Music by Arnold Strals". trove.nla.gov.au. National Library of Australia. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Library of Congress Copyright Office.The Lord's Prayer, Composer: John Serry Sr., September 2, 1992, #PAU 1-665-838

- ↑ "Lord's Prayer" at Discogs (list of releases).

- ↑ Bee Wilson, 2012, Consider the Fork: A History of How We Cook and Eat, Penguin Books ISBN 978-0-141-04908-3.

- ↑ Keith, Badman; Bacon, Tony, 1954– (2004). The Beach Boys : the definitive diary of America's greatest band, on stage and in the studio (1st ed.). San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930818-4. OCLC 56611695.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ihnat, Gwen (30 June 2015). "A Yaz song proved that electronic pop could have soul". A.V. Club. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ↑ Ferlinghetti, Lawrence (11 September 2008). Last Prayer. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ↑ "Zubiri says 'Ama Namin' drag video 'blasphemous'; CBCP won't file complaint". ABS-CBN News. 13 July 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

Sources

- Albright, W.F. and C.S. Mann. "Matthew." The Anchor Bible Series. New York: Doubleday & Co., 1971.

- Augsburger, Myron. Matthew. Waco, Texas: Word Books, 1982.

- Barclay, William. The Gospel of Matthew: Volume 1 Chapters 1–10. Edinburgh: Saint Andrew Press, 1975.

- Beare, Francis Wright. The Gospel According to Matthew. Oxford: B. Blackwell, 1981.

- Black, C. Clifton (2018). The Lord's Prayer. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-1-6116489-3-5.

- Bossuet, Jacques-Bénigne (1900). "Day 22 - 27: The Lord's Prayer". . Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Brown, Raymond E. The Pater Noster as an Eschatological Prayer, article in Theological Studies (1961) Vol. 22, pp. 175–208: from the website of Marquette University; also reprinted in New Testament Essays (1965)

- Clark, D. The Lord's Prayer. Origins and Early Interpretations (Studia Traditionis Theologiae, 21) Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2016, ISBN 978-2-503-56537-8

- Clontz, T.E.; Clontz, Jerry (2008). The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh. Cornerstone. ISBN 978-0-9778737-1-5.

- Council of Trent (1829). "Part IV: The Lord's Prayer". . Translated by James Donovan. Lucas Brothers.

- Filson, Floyd V. A Commentary on the Gospel According to St. Matthew. London: A. & C. Black, 1960.

- Fowler, Harold. The Gospel of Matthew: Volume One. Joplin: College Press, 1968

- France, R.T. The Gospel According to Matthew: an Introduction and Commentary. Leicester: Inter-Varsity, 1985.

- Hendriksen, William. The Gospel of Matthew. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1976

- Hill, David. The Gospel of Matthew. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981

- Horstius, Jacob Merlo (1877). . The paradise of the Christian soul.

- "Lilies in the Field." A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. David Lyle Jeffrey, general editor. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans, 1992.

- Lewis, Jack P. The Gospel According to Matthew. Austin, Texas: R.B. Sweet, 1976.

- Luz, Ulrich. Matthew 1–7: A Commentary. trans. Wilhlem C. Linss. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress, 1989.

- Morris, Leon. The Gospel According to Matthew. Grand Rapids: W.B. Eerdmans, 1992.

- Richardson, Cyril C., ed. (1953). The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, Commonly Called the Didache. Vol. 1 Early Christian Fathers. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - Taylor, Richard A. (1994). The Peshiṭta of Daniel. Brill. ISBN 978-9-0041014-8-7.

- Schweizer, Eduard. The Good News According to Matthew. Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1975

- Underhill, Evelyn, Abba. A meditation on the Lord's Prayer (1940); reprint 2003.

External links

Text

Commentary

Music

- Free scores of the Lord's Prayer: Free scores at the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)