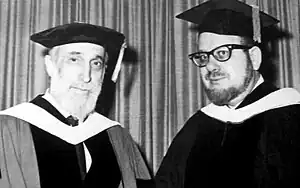

Louis Finkelstein (June 14, 1895 in Cincinnati, Ohio – 29 November 1991) was a Talmud scholar, an expert in Jewish law, and a leader of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTS) and Conservative Judaism.[1]

Biography

Louis (Eliezer) Finkelstein was born into a rabbinic family in Cincinnati on June 14, 1895. He moved with his parents to Brooklyn, New York as a youngster and graduated from the City College of New York in 1915. He received his PhD from Columbia University in 1918 and was ordained at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTS) the following year. He joined the JTS faculty in 1920 as an instructor in Talmud and went on to serve as an associate professor and professor of theology. He later became provost, president, chancellor and chancellor emeritus.

Chancellorship at JTS

Finkelstein was appointed chancellor of JTS in 1940 and remained chancellor until 1972. He positioned JTS as the central institution of Conservative Judaism, which experienced extraordinary growth during those years. Thousands of Jews living in America's cities moved to the suburbs and joined and built Conservative synagogues, and the movement emerged as the branch of Judaism with the largest number of synagogues and members. Finkelstein's leadership led Ari L. Goldman, in his obituary for Finkelstein in the New York Times, to describe Finkelstein as "the dominant leader of Conservative Judaism in the 20th century."[2] During the years of Finkelstein's leadership, the seminary flourished, growing from a small rabbinical school and teacher training program to a major university of Judaism. Finkelstein also established the seminary's Cantor's Institute, the Seminary College of Jewish Music, the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities (predecessor of the Graduate School), and a West Coast branch of the seminary that later became the University of Judaism (now the American Jewish University).

In a personal conversation, Finkelstein called the Conservative movement "a gimmick to get Jews back to real Judaism." His personal problems with the movement were reflected in his practice of coming to Conservative synagogues after having already prayed morning prayers, apparently regarding the synagogues' liturgical practices to be religiously flawed.[3]

Public outreach was among Finkelstein's top priorities. One of his signature programs was a radio and television show called The Eternal Light, which explored Judaism and Jewish holidays. Interfaith dialogue was a particular priority. Finkelstein established the Institute for Religious and Social Studies, which brought together Protestant, Roman Catholic and Jewish scholars for theological discussions. His efforts were considered so significant that an article about him was featured in Time Magazine including his picture on its cover on the edition of October 13, 1951. In 1986, the name of the institute was changed to the Finkelstein Institute in his honor.

Finkelstein's contacts went well beyond the religious community. He was an intimate of leading political and judicial figures and in 1957, enticed Chief Justice Earl Warren of the United States Supreme Court to spend a Sabbath at the seminary in the study of the Talmud. Finkelstein served as the official Jewish representative to President Franklin D. Roosevelt's commission on peace, and in 1963 President John F. Kennedy sent him to Rome as part of an American delegation to the installation of Pope Paul VI. He also offered a prayer at the second inauguration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Scholarship

Even at his busiest, Finkelstein left time for scholarship. Friends said he rose every morning at 4 A.M. to study and write until he went to synagogue at 7 A.M. He was the author or editor of more than 100 books, both scholarly and popular. He described the major influences upon his scholarship as Rabbi Professors Solomon Schechter, Louis Ginzburg, Alexander Marx and Saul Lieberman.[4]

Finkelstein authored a number of books, including Tradition in the Making, Beliefs and Practices of Judaism, Pre-Maccabean Documents in the Passover Haggadah, Introduction to the Treatises Abot and Abot of Rabbi Nathan (1950, in Hebrew with English summary),[5] Abot of Rabbi Nathan, (a three volume series on the Pharisees), and Akiba: Scholar, Saint and Martyr. He also edited a four volume series entitled The Jews: Their History, Culture and Religion in 1949; in 1971, it was renamed and published as three volumes, The Jews: Their History; The Jews: Their Religion and Culture; and The Jews: Their Role in Civilization. Among his other works were "New Light from the Prophets," published in 1969.

His major scholarly pursuits were works on the Pharisees, a Jewish sect in second Temple times from which modern Jewish tradition developed, and the Sifra, the oldest rabbinic commentary on the book of Leviticus, which was completed in Palestine in the fifth century. Even in his retirement he continued writing, working at the dining room table of his Riverside Drive apartment to complete several annotated volumes of the Sifra.

When he became frail in his later years and had trouble walking to the synagogue, his former students turned his home into a synagogue on Saturday mornings, assembling the quorum of 10 needed for prayer. After his death in 1991 this group evolved into Kehilat Orach Eliezer (KOE), which means "Congregation of the Way of Eliezer" (Eliezer Aryeh was Louis Finkelstein's given name in Hebrew), and became notable for being a large halakhic congregation that nevertheless strives to accommodate women's participation in public prayer services as much as possible within the parameters established by Jewish law as the group understands it. It meets on Manhattan's Upper West Side.[6] After Finkelstein's death, Rabbi Professor David Weiss Halivni served as rabbi of the congregation until emigrating to Israel in 2005.

References

- ↑ Glazer, N (1957) American Judaism, UCP.

- ↑ Goldman, Ari L. (30 November 1991). "Louis Finkelstein, 96, Leader of Conservative Jews". The New York Times.

- ↑ Jack Wertheimer, Jews in the Center: Conservative Synagogues and their Members, Rutgers University Press, 2002. Page 14.

- ↑ Introduction to his edition of Avot of Rabbi Natan, New York 1951.

- ↑ Hebrew: מבוא למסכתות אבות ואבות דרבי נתן (Mabo le-Massektot Abot ve-Abot d'Rabbi Natan). Table of Contents in two pages: 1 & 2.

- ↑ See "KOE :: Welcome Letter". Archived from the original on 2000-04-22. Retrieved 2007-02-09.

External links

- Bibliography of the Writings of Louis Finkelstein

- Section regarding Louis Finkelstein in "Conservative Judaism" excerpt

- Rabbi Michael B. Greenbaum's book on Louis Finkelstein And The Conservative Movement