Lu Shijia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Born | Lu Xiuzhen March 18, 1911 | ||||||||

| Died | August 29, 1986 (aged 75) Beijing, China | ||||||||

| Nationality | Chinese | ||||||||

| Alma mater | Beijing Normal University University of Göttingen (PhD) | ||||||||

| Spouse |

Zhang Wei (m. 1941) | ||||||||

| Scientific career | |||||||||

| Institutions | Beihang University | ||||||||

| Doctoral advisor | Ludwig Prandtl | ||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 陸士嘉 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 陆士嘉 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

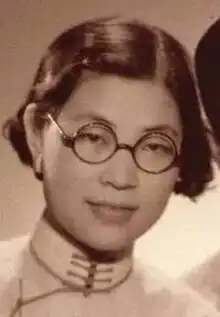

Lu Shijia (Chinese: 陆士嘉; March 18, 1911 – August 29, 1986), also known as Hsiu-Chen Chang-Lu,[1][2] was a Chinese physicist and aerospace engineer who helped create China's first high-speed wind tunnel. She founded and chaired the aerodynamics program at Beihang University, the first in the country.

Early life and education

She was born Lu Xiuzhen (Chinese: 陆秀珍; Wade–Giles: Lu Hsiu-chen) in Suzhou (Soochow) on March 18, 1911, the final year of the Qing dynasty.[3] Her ancestral home was Xiaoshan, Zhejiang.[4] Soon after she was born, her grandfather Lu Zhongqi, who served as Governor of Shanxi, and her father Lu Guangxi, were both killed by Yan Xishan during the Xinhai Revolution.[1][5] Her superstitious mother blamed the baby for her father's death, and gave her away to be raised by a paternal uncle.[1]

She attended the primary school and the High School Affiliated to Beijing Normal University, where Qian Xuesen and her future husband Zhang Wei were her classmates.[6] Inspired by Marie Curie,[3] she entered the Physics Department of Beijing Normal University as the only female student. After graduating in 1933, she taught at the Fifth Women's Normal School in Daming, Hebei, and Zhicheng Middle School in Beijing.[1]

With financial help from her maternal uncle, the renowned doctor Shi Jinmo, Lu went to study in Germany in 1937.[1] She studied at Göttingen University and received her Ph.D. in fluid mechanics in 1942. Her supervisor was Ludwig Prandtl, one of the founders of modern fluid mechanics. She was the only Chinese student and the only female graduate student of Prandtl.[4][6]

Career

After the end of the Second World War, Lu returned to China in 1946. She taught at Tongji University, the Aeronautics Department of Peiyang University, and the Institute of Hydraulic Engineering of Tsinghua University.[3][1] She joined the China Democratic League in 1951.[7]

In 1952, Lu became a member of the preparatory committee for the establishment of the Beijing Institute of Aeronautics (now Beihang University). In 1962, she founded Beihang's aerodynamics program, the first in China, and served as its first chair.[3][8] At Beihang she helped create China's first high-speed wind tunnel.[3][4]

When the Chinese Academy of Sciences resumed its election for academicians in 1980 after the end of the Cultural Revolution, Lu was nominated twice, but she declined both times and insisted on giving the opportunity to a younger scientist.[3][1]

She was a member of the first, second, and third National People's Congresses, the fifth and sixth CPPCC Standing Committees, the Standing Committee of the China Democratic League Central Committee, and the Executive Committee of the All-China Women's Federation. She also served as Vice Chair of the China Aerodynamics Research Association.[3]

Personal life

In 1941, Lu married scientist Zhang Wei, her elementary school classmate, in Germany.[1] Zhang was a member of both the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Chinese Academy of Engineering, and served as Vice President of Tsinghua University. The couple had a son, Zhang Kecheng (张克澄), and a daughter, Zhang Kequn (张克群). Kequn's son Gao Xiaosong is a renowned musician.[9]

Death and legacy

Lu died in Beijing in August 1986, and her husband died in 2001. According to their will, their children mixed their ashes together and dispersed them in the lotus pond on the Tsinghua campus.[5]

On the first anniversary of her death, Qian Xuesen presided over a scientific symposium held in her memory. On March 18, 2017, Lu's 106th birthday, Beihang University established the Lu Shijia Laboratory, the first university laboratory in China named after a female scientist.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lee, Lily Xiao Hong (2016). Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: v. 2: Twentieth Century. Routledge. pp. 387–388. ISBN 978-1-315-49924-6.

- ↑ Analysis of a Jet in a Subsonic Crosswind: A Symposium. Scientific and Technical Information Division, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 1969. p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sun Chenhui 孙琛辉; Jia Aiping 贾爱平 (November 27, 2017). "陆士嘉:做中国的居里夫人" [Lu Shijia: I want to be China's Madame Curie]. China Education News (in Chinese). Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- 1 2 3 中国近代航空工业史 (1909–1949) [History of Modern Chinese Aviation Industry (1909–1949)] (in Chinese). China Aviation Industry Press. 2013. pp. 354–5. ISBN 978-7-5165-0261-7.

- 1 2 Bei Jiang 北绛 (October 10, 2014). "陆张"双子星"". China Science News 中国科学报. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- 1 2 "与钱学森的莫逆之交". Guangming Daily. September 6, 2017. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ↑ "陆士嘉". Chinese Society of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics (in Chinese). January 1, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- ↑ "New Developments in Science & Technology: 60th Anniversary Special Issue Beihang University (BUAA)" (PDF). Sponsored Supplement to Science. 338 (6104): 39. October 2012. Bibcode:2012Sci...338S.274.

- ↑ Zhang, Kecheng (July 23, 2019). "他是高晓松的舅舅,钱学森管他的母亲叫"师姑"". Supplement to Beijing Daily. Retrieved December 1, 2019.