A lubok (plural lubki, Cyrillic: Russian: лубо́к, лубо́чная картинка) is a Russian popular print, characterized by simple graphics and narratives derived from literature, religious stories, and popular tales. Lubki prints were used as decoration in houses and inns. Early examples from the late 17th and early 18th centuries were woodcuts, followed by engravings or etchings, and from mid-19th century lithography. They sometimes appeared in series, which might be regarded as predecessors of the modern comic strip. Cheap and simple books, similar to chapbooks,[1] which mostly consisted of pictures, are called lubok literature or (Cyrillic: Russian: лубочная литература). Both pictures and literature are commonly referred to simply as lubki. The Russian word lubok derives from lub - a special type of board (secondary phloem) on which pictures were printed.

Background

Russian lubki became a popular genre during the last half of the 17th century.[2] Russian lubok was primarily influenced by the "woodcuts and engravings done in Germany, Italy, and France during the early part of the 15th century".[3] Its popularity in Russia was a result of how inexpensive and fairly simple it was to duplicate a print using this new technique.[3] Luboks were typically sold at various marketplaces to the lower and middle classes. Lubki production was concentrated in Moscow around Nikolskaya Street.[4] This type of art was very popular with these two social classes because they provided them with an inexpensive opportunity to display artwork in their houses.[5] Religious themes were prominent until 1890, when secular subjects became more prevalent. Production numbers of lubok reached 32,000 titles in 1914, with circulation numbers of 130 million.[6]

The original lubki were woodcuts.[7] The Koren Picture-Bible (1692-1696) established the most prominent style, an "Old Russian" rendering of international iconography and subjects, most closely related to the frescos of the Upper Volga.[8] By mid-18th century, however, the woodcuts were mostly replaced with engraving or etching techniques, which enabled the prints to be more detailed and complex.[9] After printing on paper, the picture would be hand-colored with diluted tempera paints.[10] While the prints themselves were typically very simplistic and unadorned, the final product, with the tempera paint added, was surprisingly bright with vivid colors and lines. The dramatic coloring of the early woodcut prints was to some extent lost with the transfer to more detailed engravings.[7]

In addition to the images, these folk prints also included a short story or lesson that correlated to the picture being presented. Russian scholar Alexander Boguslavsky claims that the lubok style "is a combination of Russian icon and manuscript painting traditions with the ideas and topics of western European woodcuts".[7] Typically, the lubok's artist would include minimal text that was supplementary to the larger illustration that would cover the majority of the engraving.

Lubok genres

Folklorist Dmitri Rovinsky is known for his work with categorizing lubok. His system is very detailed and extensive, and his main categories are: "icons and Gospel illustrations; the virtues and evils of women; teaching, alphabets, and numbers; calendars and almanacs; light reading; novels, folktales, and hero legends; stories of the Passion of Christ, the Last Judgement, and sufferings of the martyrs; popular recreation including Maslenitsa festivities, puppet comedies, drunkenness, music, dancing, and theatricals; jokes and satires related to Ivan the Terrible and Peter I; satires adopted from foreign sources; folk prayers; and government sponsored pictorial information sheets, including proclamations and news items".[7] Jewish examples exist, as well, mostly from Ukraine. Many lubki can be classified into multiple categories.

- Russian 'lubki'

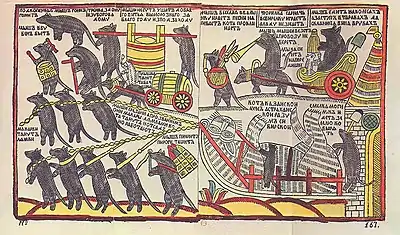

.jpg.webp) A Joker and His Wife. This 18th-century lubok is an adaptation of a German print.

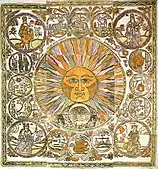

A Joker and His Wife. This 18th-century lubok is an adaptation of a German print. A depiction of the zodiac

A depiction of the zodiac The Goat and the Bear (late 19th century).

The Goat and the Bear (late 19th century). A Monster from Hell. A 19th-century Russian hand-coloured lubok

A Monster from Hell. A 19th-century Russian hand-coloured lubok A modern rural shed with lubok decoration

A modern rural shed with lubok decoration

War lubok

_%D0%9E%D0%B1%D0%BC%D0%B0%D0%BD%D1%83%D1%82%D1%8B%D0%BC_%D0%91%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%82%D1%8C%D1%8F%D0%BC_(Die_entschlossenen_Br%C3%BCder)._1918._103_x_68_cm._(Slg.Nr._475).jpg.webp)

The satirical version played an important role in the luboks from Russian wartime. It is used to present Napoleon in a satirical manner while portraying the Russian peasants as the heroes of the war. This also inspired other Russians to help fight the war by attempting to, "…redefine Russian national identity in the Napoleonic era" (Norris 2). The luboks presented a manner for the Russians to mock the French enemy, while at the same time display the 'Russianness" of Russia. "These war luboks satirized Napoleon and depicted French culture as degenerate" (Norris 4). The lubok was a means of reinforcing the idea of defeating the French invaders and displaying the horrible destruction Napoleon and his army caused Russia. To help rekindle the Russian spirit the luboks displayed "The experience of the invasion and subsequent Russian winter rendered Napoleon and his troops powerless, and the luboks illustrated this view by depicting the French leader and soldiers as impotent when confronted by peasant men, women, and Cossacks" (Norris 9). All the different representation of the Russian heroes helped define and spread the belief in Russian identity.

Russo-Japanese War lubok

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 began on February 8, 1904, at Port Arthur with a surprise attack by the Imperial Japanese Navy. At the time, "Russia was an established European power with a large industrial base and a regular army of 1.1 million soldiers. Japan, with few natural resources and little heavy industry, had an army of only 200,000 men".[11] Because of the staggering difference in military defense, Russia assumed itself to have the upper hand before the war ensued. Luboks depicting the overconfidence of the Russian army were created because censorship laws at the time did not allow satirical magazines to subsist.

With the use of satirical, often racist cartoons, luboks displayed pictures such as, "a Cossack soldier thrashing a Japanese officer, and a Russian sailor punching a Japanese sailor in the face".[12] These luboks, produced in Moscow and St. Petersburg, were anonymously created and recorded much of the Russo-Japanese War.

Perhaps due to the Russians' overconfidence, "During the battle, the Japanese generals were able to size up their opponent and predict how he would react under certain circumstances. That knowledge enabled them to set a trap and defeat a numerically superior enemy".[13] Therefore, the Russian government eventually stepped in with its censor laws and stopped the creation of more satirical luboks. All in all, around 300 luboks were created during 1904–05.

See also

References

- ↑ Lyons, Martyn. Books: A Living History. Getty Publishing, 2011, 158.

- ↑ Farrell, Dianne Ecklund. "Medieval Popular Humor in Russian Eighteenth-Century Lubok". pp. 552

- 1 2 Farrell, Dianne Ecklund. "The Origins of Russian Popular Prints and Their Social Milieu in the Early Eighteenth Century." p. 1

- ↑ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: a Living History. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Publications. p. 158. ISBN 9781606060834.

- ↑ Jahn, Hubertus F. "Patriotic Culture in Russia During World War I". Cornell University Press: Ithaca and London. p.12

- ↑ Lyons, Martyn (2011). Books: A Living History. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. pp. 158–159. ISBN 9781606060834.

- 1 2 3 4 Boguslawski, Alexander (29 January 2007). "Russian Lubok (Popular Prints)". Retrieved 2012-10-01.

- ↑ A.G. Sakovich, Russkaia gravirovannia kniga Vasiliia Korenia, 1692-1696, Moscow, Izdatelstvo "iskusstvo", 1983.

- ↑ Jahn, Hubertus F. "Patriotic Culture in Russia During World War I". Cornell University Press: Ithaca and London. p.12

- ↑ "Russian Lubok - The Russian Project". 29 January 2007. Retrieved 2012-10-01.

- ↑ Albro, Walk. "Russo-Japanese War's Greatest Land Battle." Military History 21.6 (2005): 58-65.

- ↑ Bryant, Mark. "The Floating World at War." History Today 56.6 (2006): 58-59.

- ↑ Albro, Walk. "Russo-Japanese War's Greatest Land Battle." Military History 21.6 (2005): 58-65.

Bibliography

- Adela Roatcap, 'Lubki The Wood Engravings of Old Russia', in Parenthesis; 10 (2004 November), p. 22-23

- Norris, Stephen. 'Images of 1812: Ivan Terebenev and the Russian Wartime Lubok', in National Identities; 7 (2005): pp. 1–15.doi:10.1080/14608940500072909

- Farrell, Dianne, 'Shamanic Elements in Some Early Eighteenth Century Russian Woodcuts', in Slavic Review; 54 (1993): pp. 725–744.