| Lubostroń Palace | |

|---|---|

Pałac w Lubostroniu | |

.jpg.webp) Lubostroń Palace

Lubostroń Palace (Poland)  Lubostroń Palace (Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship) | |

| General information | |

| Type | Palaces |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical architecture |

| Classification | Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship Heritage List Nr.604016, A/290/1-5 (March 10, 1933 and 1994)[1] |

| Location | Lubostroń, Poland |

| Address | Lubostroń, 37 |

| Current tenants | Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship |

| Construction started | 1780 |

| Inaugurated | 1800 |

| Technical details | |

| Size | Park 40 hectares (99 acres) |

| Design and construction | |

| Engineer | Stanisław Zawadzki |

| Known for | Classical concerts |

| Website | |

| http://palac-lubostron.pl/ | |

The Lubostroń Palace is a neoclassical palace, built in 1795-1800 by Stanisław Zawadzki, a leading architect of the time. Author, among others, of edifices in Warsaw and in the region of the Greater Poland, Zawadzki was commissioned by Count Fryderyk Skórzewski to realize the project on the location of the Piłatowo folwark. The complex has been registered on the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship Heritage List.

History

The Łabiszyn estate was brought in the dowry of Marianna née Ciecierska in 1762, when she married the count Franciszek Skórzewski (1709-1773),[2] a general of the Crown troops, supporting the Bar Confederation. Marianna was beautiful and brilliant, shining at the royal court in Berlin and at Sanssouci: King Frederick II even became the godfather of their first son, Fryderyk.[3] In spring 1772, she was visited by Franz von Brenkenhoff, mandated by Frederick II to collect demography data in the area, in the perspective of the First Partition of Poland.[4]

After he inherited the estate, Fryderyk Józef Andrzej (1768-1832) became a Count of the Prussian Empire, chamberlain of the court and Grand Cross in the Order of the Red Eagle.[5] He initiated the project to raise a palace there, on the territory of the village of Piłatowo. The name Lubostroń was forged by Fryderyk himself, in reference to the Polish wording Lube ustronie (English: Pleasant retreat).[6]

Fryderyk commissioned Stanisław Zawadzki (1743–1800) to realize this scheme. The latter was a famous architect of his time, educated in Rome. He was known for designing buildings in Warsaw, Kamianets-Podilskyi and palaces in Dobrzyca and in Śmiełów (region of Greater Poland).[7] Zawadzki's design at Dobrzyca brought him in contact with Skórzewski, as Dobrzyca's palace was owned by Fryderyk's sister, Aleksandra Augustynowa Gorzeńska.[8]

Most likely, the design aimed at recalling the famous Villa Rotonda near Vicenza, created in 1550 by the Italian architect Andrea Palladio.[9]

After the completion of exteriors, interiors decoration works took five more years to be achieved. Most of the columns in the Lubostroń Palace used material previously assigned to the building of the Temple of Divine Providence in Warsaw. Planned to become the place where people would vote for the Constitution of 3 May 1791, the edifice could not be erected because of the Third Partition of Poland.[7] The Temple of Divine Providence was eventually completed in 2016.

Designed as the new seat of the Skórzewski family, Fryderyk moved there in 1808, while the palace was not yet completed. The construction of the residential complex has undoubtedly been completed before 1815, as in November 1814, Count Fryderyk hosted there a wedding. The palace once completed became an informal seat of the representative authorities of the Duchy of Warsaw. Important personalities of the Napoleonic era stayed here. It became a manifesto of the ancestral patriotism of the family, complemented by decoration elements: busts of famous Poles and a painting gallery of Polish kings, princes and hetmans, such as Frederick Augustus - the Duke of Warsaw.[3]

Ignacy Chodźko (1794-1861), a Polish novelist and storyteller, commented in one of his work at the end of the 1830s:[9]

(...) Near the Noteć and the town of Łabiszyn in the Grand Duchy of Poznań, there is a palace in Lubostroń. Its location is stunning, the charm of its gardens and the beautiful architectural realisations designed under the direction of Stanisław Zawadzki make this property one of the most noteworthy in Poland (...)

Leon Fryderyk Walenty Skórzewski (1845-1903), Fryderyk's descendant, invited in 1872 to the palace Erazm Rykaczewski (1803-1873), a famous Polish historian, translator and lexicographer, who died here a year later. Among the other famous people who visited the palace during the 19th century, one can mention:[10] Stefan Garczyński, Adam Mickiewicz in 1831,[11] Wincenty Pol, Gustaw Zieliński (1809-1881) or Emilia Sczaniecka (1804-1896).

The estate remained in the hands of various branches of the Skórzewski family until the outbreak of World War II. At the end of the conflict, it became initially a training centre of the District Council of Trade Unions in Bydgoszcz.[6] Afterwards, the place was managed by the local State Agricultural Farm and housed, among others, a center of the Employee Holiday Fund (Polish: Fundusz Wczasów Pracowniczych).

In the 1960s, Andrzej Szwalbe, then director of the Pomeranian Philharmonic in Bydgoszcz, took interest in the aging palace. Urging the voivodeship to carry out renovation, he decided to revive the monument via music performances. Hence, during the first Bydgoszcz Music Festival in 1963, concerts were organized in the rotunda of the Lubostroń palace with most of the audience brought from Bydgoszcz by buses.[9] One of the first recitals occurred on May 8, 1963, with a performance of the Bydgoszcz Chamber orchestra (Capella Bydgostiensis) directed by Stanisław Gałoński. During the following iteration of the festival, the palace housed Polish medieval compositions of Stanisław Moniuszko.

This tradition of concerts still lasts today, with various Polish and foreign artists, guests of the different Bydgoszcz Festivals (e.g. Musica Antiqua Europae Orientalis).[9]

In 1991, the State Agricultural Farm was liquidated and the estate was taken over by the state. The ensemble underwent major renovations, setting up a palace-and-park complex with a hotel and a restaurant, hosting diverse activities. Since January 1, 2013, the complex is managed by the Kujawsko-Pomorskie Voivodeship.[8]

Nowadays, music events are regularly performed by Bydgoszcz artists: musicians from the Pomeranian Philharmonic or the Opera Nova Bydgoszcz, as well as teachers and students of the Music Academy. In addition, the university of Bydgoszcz initiated a series of Sunday "Palace Concerts", consisting in particular of recitals, chamber ensembles and choirs or thematic performances.[12] The famous composer Krzysztof Penderecki planted a black pine tree in the park during a stay.[13]

In 2021-2022, the Bydgoszcz Music Academy planned to have a monthly performance in the palace.[14]

Furthermore, the Lubostroń Palace, as a cultural institution, houses other events, such as vernissages and theater plays in parallel with the activity of its hotel and restaurant. The palace ensemble has been listed in 1933 and 1994 on the Heritage registry of the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship.[15]

Architecture

The shape of the palace refers originally to Palladio's villas from the 1570s: Villa Capra "La Rotonda" (1571) and Villa Trissino in Sarego. In Poland, the Lubostroń Palace was preceded only by two realisations, Warsaw's Królikarnia by Domenico Merlini (1786) and Lubomirski Palace (1780s).[3] The Palace does not display an absolute symmetry in the layout of the rooms and the façades, so characteristic of the Palladio masterpiece. It has a square footprint with a circular three-storey hall in the center. Despite deviations from the rigid Palladian rules, the building gives the impression of a perfectly harmonious work, with a magnificent silhouette.

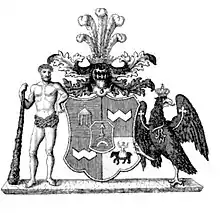

Stairs lead to the main portico boasting eight giant order columns. The portico is topped with a pediment bearing two coats of arms:[3]

- to the right Fryderyk Skórzewski's, as count of Prussia;

- to the left Garczyński's, referring to Antonina Garczyńska (1770-1824) Fryderyk's wife.

Moreover, the portico bears the inscription SIBI AMICITIAE ET POSTERIS MDCCC (English: To Myself, My Friends and Descendants 1800). Every other facades exhibit a wall portico supported by four giant order columns, topped with a triangular pediment.

The palace floor is richly adorned with marquetry depicting the Polish Eagle and the Coat of arms of Lithuania. In the side rooms (e.g. boudoir, library)[3] are displayed murals by Antoni and Franciszek Smuglewicz[10] or Jan Bogumił Plersch. The palace additionally comprises a private chapel and cellars (under the rotunda).[3]

Rotunda

The edifice is a two-storey building with a central three-level rotunda roofed with a copper sheet covered dome. The latter is crowned with a bronze figure of Atlas designed by Władysław Marcinkowski at the end of the 19th century.[7] Stuccoes of the rotunda hall were realized by Michał Ceptowski from Poznań.[10]

Under the dome, 10 metres (33 ft) large and 15.5 metres (51 ft) high,[3] runs a frieze depicting ancient sacrificial processions. Above it are placed four relief slabs, by Michał Ceptowski, illustrating local historical events:[8]

- King Władysław I Łokietek and Florian Szary at the Battle of Płowce (1331);

- Queen Jadwiga meeting Konrad von Jungingen, Grand Master of the Teutonic Order in Inowrocław (1397);

- the Battle of Koronowo (1410);

- Marianna Skórzewska, Fryderyk 's mother, presenting the plans of the Bydgoszcz Canal to Frederick the Great (1773).

The dome adorning is complemented by a huge brass chandelier hanging from the top. The capitals and bases of the columns standing in the rotunda originate from the then unbuilt Temple of Divine Providence in Warsaw.[16]

Other buildings and park

Next to the palace stand various edifices also designed by Zawadzki:[10]

- a neoclassicist old mansion which served as an outbuilding (end of 18th century);

- stables and coach house (19th century), which have been converted into a restaurant.

Additionally one can notice later neo-gothic farm buildings and a hunting lodge.[13]

The palace is surrounded by a landscape park covering approximately 40 hectares (99 acres) and partially integrated into the nearby forest. Its designer was Oskar Teichert.[17]

On the night of August 2, 2017, a storm destroyed about 200 trees including 4 monumental lime trees.[18] Another storm on the night of August 11, 2017, brought further destruction to natural monuments and damaged the orangery,[19][20] the administration office, the former coach house and the stables.[21]

Gallery

Bird eye view

Bird eye view Facade onto the park

Facade onto the park Atlas statue topping the dome

Atlas statue topping the dome.jpg.webp) Rotunda interiors

Rotunda interiors Relief depicting Marianna Skórzewska and Frederick the Great

Relief depicting Marianna Skórzewska and Frederick the Great Side room

Side room Chapel

Chapel Administrative office

Administrative office Palace orangery

Palace orangery Old stable and coach house

Old stable and coach house View of the park

View of the park

See also

References

- ↑ Załącznik do uchwały Nr XXXIV/601/13 Sejmiku Województwa Kujawsko-Pomorskiego z dnia 31 marca 2021 r

- ↑ redakcja autoflesz.com (2021). "Historia pałacu Skórzewskich w Lubostroniu – warto zwiedzić i poznać jego tajemnice". autoflesz.com. AutoFlesz. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jankowski, Aleksander (2019). Lubostrońska Villa Rotonda w XVIII–XIX w. Pałac "mieszkalny, ale do mieszkania niemiły". Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej 67. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Archeologii i Etnologii Polskiej Akademii Nauk. pp. 233–258.

- ↑ Spude, Franz (1880). Franz Baltasar Schönberg von Brenkenhof. Landsberg: Landsberg a. W.

- ↑ Hermann, Hans Otto (1830). Chateau de Lubostroń dans le Grand-Duché de Posen propriété du Comte Frédéric Skórzewski, chambellan et grand croix de l'ordre de l'aigle rouge. Berlin: Druck. von M.G. Helmlehner.

- 1 2 Podgóreczny, Józef (1971). Niedaleko Bydgoszczy leży Lubostroń. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 59–64.

- 1 2 3 Jaroszewski, Tadeusz. S. (2000). Pałace w Polsce (Przewodnik). Warszawa: Muza. pp. 94–99. ISBN 8372005850.

- 1 2 3 "Historia". palac-lubostron.pl. Pałac Lubostroń. 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Pruss Zdzisław, Weber Alicja, Kuczma Rajmund (2004). Bydgoski leksykon muzyczny. Bydgoszcz: Kujawsko-Pomorskie Towarzystwo Kulturalne. pp. 328–329. ISBN 8372005850.

- 1 2 3 4 Paweł Anders, Witold Gostyński, Bogdan Kucharski, Włodzimierz Łęcki, Piotr Maluśkiewicz, Jerzy Sobczak (1995). 123 x Wielkopolska. Poznań: Wojewódzka Biblioteka Publiczna. pp. 93–95. ISBN 8385811257.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Jucewicz, Jerzy Adalbert (1978). Mickiewicz gościem Samostrzela i Lubostronia. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 122–125.

- ↑ "Jubileusz Pałacu Lubostroń". kujawsko-pomorskie.pl. Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Kujawsko-Pomorskiego. 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- 1 2 Bejmajoanna, Joanna (22 January 2016). "Hr. Leon Skórzewski nie wróci do Lubostronia. To on wróci do niego?". plus.pomorska.pl. Polska Press Sp. z.o.o. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ↑ "KONCERT PAŁACOWY". amuz.bydgoszcz.pl. Akademia Muzyczna im. Feliksa Nowowiejskiego w Bydgoszczy. 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ↑ Załącznik do uchwały Nr XXXIV/601/13 Sejmiku Województwa Kujawsko-Pomorskiego z dnia 31 marca 2021 r

- ↑ AB (1 May 2021). "Majówka 2021. Nasze propozycje na długi majowy weekend. Warto zobaczyć te miejsca". pomorska.pl. Polska Press Sp. zo.o. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ↑ SOBERSKI, KAROL (2020). "Tajemniczy park w Czerniejewie". pojezierze24.pl. pojezierze24. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ↑ as (3 August 2017). "Pałac w Lubostroniu po burzy. 200 zniszczonych drzew". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ↑ as (12 August 2017). "Burza w okolicach Bydgoszczy. Oto obraz zniszczeń". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ↑ as (16 August 2017). "Tak wyglądał park obok Pałacu w Lubostroniu po burzy". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ↑ al (1 April 2019). "Zabytkowy park przy podbygoskim pałacu zostanie odtworzony". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

External links

Bibliography

- (in Polish) Pruss Zdzisław, Weber Alicja, Kuczma Rajmund (2004). Bydgoski leksykon muzyczny. Bydgoszcz: Kujawsko-Pomorskie Towarzystwo Kulturalne. pp. 328–329. ISBN 8372005850.

- (in Polish) Paweł Anders, Witold Gostyński, Bogdan Kucharski, Włodzimierz Łęcki, Piotr Maluśkiewicz, Jerzy Sobczak (1995). 123 x Wielkopolska. Poznań: Wojewódzka Biblioteka Publiczna. pp. 93–95. ISBN 8385811257.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - (in Polish) Jankowski, Aleksander (2019). Lubostrońska Villa Rotonda w XVIII–XIX w. Pałac "mieszkalny, ale do mieszkania niemiły". Warszawa: KWARTALNIK HISTORII KULTURY MATERIALNEJ. pp. 233–258.

- (in Polish) Stanisław Lorentz, Andrzej Rottermund, Henryk Białoskórski (1984). Klasycyzm w Polsce. Warszawa: Arkady. pp. 262–263. ISBN 8321330827.

52°54′25″N 17°52′53″E / 52.90694°N 17.88139°E