Paleontology in South Dakota refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of South Dakota. South Dakota is an excellent source of fossils as finds have been widespread throughout the state.[1]: 254–255 During the early Paleozoic era South Dakota was submerged by a shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures like brachiopods, cephalopods, corals, and ostracoderms. Local sea levels rose and fall during the Carboniferous and the sea left completely during the Permian. During the Triassic, the state became a coastal plain, but by the Jurassic it was under a sea where ammonites lived. Cretaceous South Dakota was also covered by a sea that was home to mosasaurs. The sea remained in place after the start of the Cenozoic before giving way to a terrestrial mammal fauna including the camel Poebrotherium, three-toed horses, rhinoceroses, saber-toothed cat, and titanotheres. During the Ice Age glaciers entered the state, which was home to mammoths and mastodons. Local Native Americans interpreted fossils as the remains of the water monster Unktehi and used bits of Baculites shells in magic rituals to summon buffalo herds. Local fossils came to the attention of formally trained scientists with the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The Cretaceous horned dinosaur Triceratops horridus is the South Dakota state fossil.

Prehistory

No Precambrian fossils are known from South Dakota, so the state's fossil record does not begin until the Paleozoic. At the start of the Paleozoic South Dakota was submerged by a sea. The state's Cambrian life left behind a rich trace fossil record. Paleozoic marine life of South Dakota included brachiopods, cephalopods, and corals. The sea temporarily withdrew from South Dakota during the Ordovician period.[2] But, in the middle or late Ordovician, ostracoderms swam over South Dakota. Similar ostracoderms were preserved near Canon City, Colorado.[1]: 258 Later, during the Carboniferous period, sea levels again began to rise and fall. Marine life from this time included brachiopods and corals, but the rock record preserves evidence for local brackish and freshwater environments as well. The sea withdrew from the state altogether during the Permian and local sediments began being eroded rather than deposited.[2]

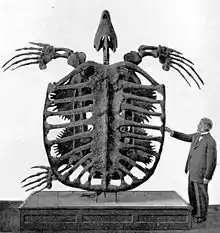

During the Triassic period sedimentation resumed. The geologic record reveals that South Dakota was moist coastal plain at that time. Seawater once more covered South Dakota during the Jurassic. This sea was home to creatures like ammonites, clams, crinoids, and starfish. As the sea retreated South Dakota became a terrestrial environment dotted with lakes, streams, and swamps. The state was covered again by the sea during the Cretaceous period.[2] This sea was called the Western Interior Seaway.[3]: 5 This sea was home to many invertebrates, aquatic birds, and marine reptiles.[2] The Cretaceous life of South Dakota was similar to that of Wisconsin.[1]: 256 Some of South Dakota's ammonites were very unusual for the group.[1]: 256 During the Late Cretaceous the region now occupied by the Black Hills of South Dakota may have attracted long necked plesiosaurs from hundreds of miles away as a source of gastroliths.[4]: 137–138 Short-necked plesiosaurs like Dolichorhynchops also lived in the Western Interior Seaway of South Dakota during the Campanian. They were fast swimmers who fed on contemporary small fish and cephalopods. Most short-necked plesiosaurs were relatively small, with body lengths of less than ten feet. However, one South Dakotan individual was 6–7 meters (20–23 ft) long.[4]: 129 More shark species are known from the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway deposits of South Dakota than other states with rocks from the same environment like those of Kansas.[5]: 66 Otherwise these two states had similar shark communities.[5]: 69 During the Late Campanian, South Dakota was home to the colossal sea turtle Archelon ischyros. The first specimen was 3.5 meters (11 feet) long.[6]: 108 Archelon is the largest known turtle in history. Its size is comparable to that of a small car.[6]: 114 Also during the Cretaceous, geologic uplift was forming the Black Hills in the western part of the state.[2] Local dinosaurs included the armored Edmontonia, duck-billed Edmontosaurus, the ostrich dinosaur Ornithomimus, Pachycephalosaurus, Triceratops, and Tyrannosaurus.[7]

During the early part of the Cenozoic, central and eastern South Dakota was still covered by the sea. The uplift responsible for the Black Hills continued to elevate their topography.[2] As the Cenozoic continued the sea shrank away from the state. In its place, grasslands formed and were roamed by herds of grazing mammals.[2] Later, during the Oligocene, at least part of South Dakota was covered in seawater.[1]: 256 The White River Formation was being deposited in the White River badlands as the sea gradually receded.[1]: 255–257 The Oligocene flora left behind few fossils, but among them were hackberry seeds and petrified wood.[1]: 256 Although plant fossils are scarce, these deposits preserve one of the best Tertiary mammal faunas in the world.[1]: 255–257 More than 175 different kinds of animals were preserved from this time.[1]: 256 The local mammals included the three-toed horses, pig-like animals, the camel Poebrotherium, Protoceras, rhinoceroses, rodents, saber teeth, tapirs, and titanotheres.[1]: 255–256 Contemporary birds also left behind bones and even an egg. These are significant because bird fossils are very rare.[1]: 256 Many streams carried even more sediment into the region from the young Rocky Mountains and Black Hills.[1]: 256–257 At the time South Dakota consisted of plains dotted with marshes and shallow lakes and split by wide streams.[1]: 257 Some of the local Oligocene wildlife left behind footprints that would later fossilize. The Brule Formation preserves one of only seven Oligocene fossil tracksites in the western United States.[8]: 260 Volcanic activity sporadically showered the state with ash.[2] During the Ice Age, glaciers scoured the state. As they melted, they deposited sediments that would preserve the fossil remains of creatures like bison, horses, mammoths, and mastodons.[2]

History

Indigenous interpretations

Fossils feature in some of the legends of local people. The Sioux believed that in the first creatures in creation were the insects and reptiles, who were ruled by the Water Monster Unktehi. Reptiles were very diverse and came in all shapes and sizes, but they became violent and bloodthirsty until they were petrified by lightning sent by the Thunder Birds. The physical bodies of the Thunder Beings killed by the lightning, including Unktehi, also ended up being buried. The Sioux believe that earth has a history of four distinct ages. These events occurred during the Age of Rock. This portrayal of the Thunder Birds may have been influenced by associations of fossils of the Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon with marine reptiles of the same age in the western US.[9]: 221

Local people also employed fossils in ritual. Plains Indians like the Blackfeet and Cheyenne have a tradition of using Baculites fossils to summon buffalo herds. When used this way the fossils are called "buffalo-calling stones" or Iniskim. This practice derives from the complex shapes of the fossil's internal structure, which can sometimes bear shapes resembling buffalo. Iniskim have been discovered in South Dakota archeological sites. Archeological evidence exists for the buffalo-calling stone tradition that is at least 1,000 years old.[10]: 227

One interesting South Dakota fossil was actually found not far from the Gobernador ruins in New Mexico during the 1980s. It was the jawbone of an Oligocene mammal endemic to South Dakota. This means someone would have had to transport the bone for 800 miles from the place it was discovered. The Blackfeet engaged in regular trade with the Cliff Dweller and Navajo peoples of the southwest, which may explain how the fossil ended up so far from its place of origin.[11]: 165–166

Scientific research

On September 10, 1804, four members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition recorded in their journals a fossil discovery along the banks of the Missouri River in what is now Gregory County of south-central South Dakota. The find was a 45-foot-long articulated vertebral column with some ribs and teeth associated that was located at the top of a high ridge. The men interpreted the remains as originating from a giant fish, but today scientists think the specimen was probably a mosasaur, or maybe a plesiosaur. The expedition sent back some of the fossils, but these were later lost.[12]: 15 Later, in 1847, Dr. Hiram A. Prout published a description of a fragmentary titanothere jaw discovered in the White River Badlands in the American Journal of Science. Not long afterward, Joseph Leidy described the Oligocene camel Poebrotherium, which was discovered in the same general region as Prout's titanothere jaw. The government responded to these discoveries by dispatching an expedition into the area. In 1850 the Smithsonian sent its own collectors into the area. The Tertiary deposits of the White River Badlands was active for decades and still ongoing in 1920 when the South Dakota School of Mines published its Bulletin No. 13. This publication summarized the results of all the paleontological fieldwork done in the White River Badlands.[1]: 255 In 1877, the United States Geological Survey published a report on the ancient plants and invertebrates of South Dakota.[1]: 255–256

In 1895, George Wieland discovered YPM 3000, the nearly complete and articulated type specimen of the giant sea turtle now known as Archelon ischyros, which had been preserved in the Pierre Shale. The discovery was the likely instigator for Wieland's subsequent research into Late Cretaceous sea turtles that began the next year. After more work reconstructing the specimen, Wieland noticed that its plastron was very similar to that of Protostega gigas and he began to doubt that Archelon was truly distinct. Therefore, in 1898, he reclassified it as a species of Protostega, P. ischyros. After examining the pelvis and skull of "Protostega" ischyros, however, Wieland recovered his confidence in his original view that YPM 3000 belonged to a genus distinct from Protostega and reclassified "P." ischyros as Archelon ischyros again.[6]: 109

Later, in 1940, the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology collaborated with National Geographic on an expedition into the badlands. They uncovered tons of fossils from at least 175 different species of Oligocene life. The fossils were taken to the South Dakota School of Mines in Rapid City. Among the mammal discoveries were the remains of rhinoceroses, tapirs, three-toed horses, pig-like animals, and rodents. The team also uncovered some bird fossils, which are very rare. One of these was a fossil egg, which author Marian Murray has called "[t]he best find" of the entire expedition. Only a few plant specimens were discovered, but these included fossil hackberry seeds and petrified wood. Some of the fossils were so precariously located that the excavators had to use block and tackle to lower the fossils down from the tops of "slender pinnacles". The fossils were preserved in channel sandstones that had received little scientific attention prior to the expedition.[1]: 256 In June 1947 the South Dakota School of mines sent another expedition into the Badlands. They uncovered a wide variety of fossils preserved in the Oligocene White River Formation. Among the creatures discovered were rhinoceroses, saber teeth, giant pig-like animals, Protoceros, tapirs, horses and more.[1]: 256 In 1990, Sue Hendrickson discovered a new specimen of Tyrannosaurus rex that would later be nicknamed in her honor.[13] The specimen made headlines when a dispute over ownership rights raged for more than five years.[14] "Sue" was determined to rightfully belong to the owner of the property it was found on. The rancher put the specimen up for auction and was purchased by the Chicago Field Museum for 8.36 million dollars.[15]

In 1996 Bell and others reported the discovery of a mosasaur of the genus Plioplatecarpus in South Dakota's Pierre Shale. The specimen was important because it preserved several juvenile skeletons inside its pelvic region. Similar fossils have been put forward as evidence of live birth in other types of marine reptiles.[4]: 139

Protected areas

- Fossil Cycad National Monument (no longer exists)

- The Mammoth Site

National Register sites by region/county

It is intended that all National Register-listed archeological sites (places that have Smithsonian trinomials) in the state be listed here. This includes sites in counties of Fall River, Custer, Pennington, Meade, and Harding in the west of the state, and Corson, Stanley, and Jackson in next north-to-south swathe of states, and Campbell, Walworth, Potter, Sully, Hughes, Hyde, Hand, Buffalo, and Lyman in the next, and from Roberts, Spinks, Beadle, Jerauld, Sanborn, Davison, Hanson, McCook, Minnehaha, Hutchinson, Turner, and Lincoln in the last. This may not be complete; other sites might be included in large historic districts or listed under non-obvious names.

Numerous archeological sites in Fall River County were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in batches in 1982, 1993, 2005 and 2016. These were deemed significant for their information potential. The specific locations of these sites are not disclosed, but their general regions are. [These should be re-arranged into regions: southern Black Hills, north Cave Hills, Sandstone Buttes, etc.]

They are:

| NRHP reference | Smithsonian Trinomial | Archeological region County |

NRHP listing date | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 93000804 | 39FA86 | Fall River | 1993-08-06 | Rock art site, including Ponca, and including inscription(s) by member(s) of the 1874 Black Hills Expedition.[16]: 380, 603 |

| 93001040 | 39FA88 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site; rock shelter and cave site[16]: 392, 603 |

| 93000806 | 39FA89 | Fall River | 1993-08-06 | Rock art site[16]: 379, 603 |

| 93001041 | 39FA90 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site; rock shelter and cave site[16]: 379, 602, 603 |

| 93001042 | 39FA99 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379, 603 |

| 93001043 | 39FA243 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site; rock shelter and cave site[16]: 379, 391–2, 603 |

| 93001044 | 39FA244 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379, 603 |

| 93001045 | 39FA316 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site, including painted rock art (see images, Figure 88, page 375)[16]: 375, |

| 93001046 | 39FA321 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site, including Ponca[16]: 343 / II-278 |

| 93001047 | 39FA395 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Middle Archaic "Pecked Realistic" rock art (see images, Figure 81 & 82); a McKean rock shelter and cave site[16]: 143, 371, 391–2 |

| 93001048 | 39FA446 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 93001049 | 39FA447 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 93001050 | 39FA448 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site; rock shelter and cave site[16]: 379, 391 |

| 93001051 | 39FA542 | Fall River | 1993-10-25 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 93000801 | 39FA678 | Fall River | 1993-08-06 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 93001052 | 39FA679 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 93001053 | 39FA680 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 93001054 | 39FA682 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 93001055 | 39FA683 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site; rock shelter and cave site[16]: 379, 391 |

| 93001056 | 39FA686 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site; rock shelter and cave site[16]: 379, 391 |

| 93001057 | 39FA688 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site; rock shelter and cave site. See photo from 2006 in Figure 92, p385.[16]: 379, 385, 391 |

| 93001058 | 39FA690 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site; see photo from 2000 showing incised cattle brands and graffiti in Figure 91, p382.[16]: 379, 382 |

| 93001059 | 39FA691 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site, Late Prehistoric.[16]: 199, 379 |

| 93001060 | 39FA767 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site; rock shelter and cave site[16]: 199, 379, 391 |

| 93001061 | 39FA788 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 93000790 | 39FA806 | South Fork of the Cheyenne Fall River County |

1993-08-06 | Rock art site[16]: 379, 404, 535 |

| 93001062 | 39FA819 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | |

| 93001063 | 39FA1010 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | |

| 93001064 | 39FA1013 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | |

| 93001065 | 39FA1046 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | |

| 93000791 | 39FA1049 | Fall River | 1993-08-06 | |

| 93001066 | 39FA1093 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | |

| 93001067 | 39FA1152 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | |

| 93001068 | 39FA1154 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | |

| 93001069 | 39FA1155 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | |

| 93001070 | 39FA1190 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | |

| 93000792 | 39FA1201 | Fall River | 1993-08-06 | |

| 93001071 | 39FA1204 | Fall River | 1993-10-20 | |

| 05000690 | 39FA1336 | Fall River | 2005-07-14 | |

| 05000689 | 39FA1337 | Fall River | 2005-07-14 | |

| 05000691 | 39FA1638 | Fall River | 2005-07-14 | |

| 16000051 | 39FA2530 | Fall River | 2016-02-23 | |

| 16000052 | 39FA2531 | Fall River | 2016-02-23 | |

| 82004771 | 39FA7 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004765 | 39FA58 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004760 | 39FA75 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004772 | 39FA79 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004773 | 39FA91 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004774 | 39FA94 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004761 | 39FA277 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004762 | 39FA389 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004764 | 39FA554 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004766 | 39FA676 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004767 | 39FA677 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004769 | 39FA681 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004768 | 39FA684 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | Pecked rock art (see MPS Figure 10, p. 33)[17]: 19, 33 |

| 82004906 | 39FA685 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 82004770 | 39FA687 | Fall River | 1982-05-20 | |

| 05000587 | 39FA1303 | Fall River | 2005-06-08 | |

| 05000586 | 39FA1639 | Fall River | 2005-06-09 | |

| 93001039 | 39CU70 | Custer | 1993-10-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 93000803 | 39CU890 | Custer | 1993-08-06 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 99000679 | 39CU1619 | Custer | 1999-06-03 | "A very large stone circle camp" site, with cairn(s) and stone circle(s)[16]: 403, 424, 427, 601 |

| 16000047 | 39CU2565 | Custer | 2016-02-23 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 16000048 | 39CU3178 | Custer | 2016-02-23 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 16000049 | 39CU3393 | Custer | 2016-02-23 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 16000050 | 39CU4164 | Custer | 2016-02-23 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 82004759 | 39CU91 | Custer | 1982-05-20 | Rock art site known as Scored Rocks, identified by a historic marker as a Lakota site, at least partly of "proto-historic" era, as depicts guns.[16]: 379, 586 |

| 82004752 | 39CU510 | Custer | 1982-05-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 82004754 | 39CU511 | Custer | 1982-05-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 82004753 | 39CU512 | Custer | 1982-05-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 82004755 | 39CU513 | Custer | 1982-05-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 82004756 | 39CU514 | Custer | 1982-05-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 82004757 | 39CU515 | Custer | 1982-05-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 82004758 | 39CU516 | Custer | 1982-05-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379 |

| 93001072 | 39PN376 | Pennington | 1993-10-25 | Rock art site known as "The Ice Cave" with red-painted handprints (see photo in Figure 117, p. 467); rock shelter(s) and cave(s) used in Paleoindian, Middle Archaic, Late Archaic, Late Prehistoric, and Historic eras[16]: 391–92, 467 |

| 82004778 | 39PN57 | Pennington | 1982-05-20 | Rock art site[16]: 379–80 |

| 82004775 | 39PN108 | Pennington | 1982-05-20 | Rock art site. See Figure 2, p58.[16]: 58, 379–80 |

| 82004776 | 39PN438 | Pennington | 1982-05-20 | Rock art site[16] |

| 82004777 | 39PN439 | South Fork Cheyenne region Pennington |

1982-05-20 | Rock art site[16] |

| 93000798 | 39MD20 | Meade | 1993-08-06 | Rock art site; has stone circle. Also listed as 39MD1, the site is in the eastern foothills of the Black Hills "lying in a deep arroyo"; the "rimrock above the arroyo contained a stone circle and a scatter of chipped stone artifacts"; the stone circle was "test excavated" and found, however, to have very little "chipping debris".[16]: 379, 397, 538 |

| 93000818 | 39MD81 | Meade | 1994-04-14 | |

| 93000797 | 39MD82 | Meade | 1994-04-14 | |

| 94000108 | 39HN1 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | Ludlow Cave, in North Cave Hills, a multiple-component ceremonial rock art site, stratified. See Figure 95: View of Ludlow Cave, p. 389. Had Early Archaic projectile points, but "these appear to be relics—that is, artifacts found and carried to a site by later people". Possible Late Archaic projectile points. See Figure 30: Late Historic projectile points, which are possibly of Avonlea complex but might possibly belong to Midle Missouri tradition, as the site includes some Mandan Tradition pottery, and was associated historically with Mandan and Hidatsa groups. Excavated using poor field methods, including that points from elsewhere may have mistakenly been mixed into its collection. It was "essentially cleaned out" in 1920 by W.H. Over. This is a McKean site. Has historic inscriptions. See Figure 95, p. 389. Late Archaic and Late Prehistoric and Historic rock shelter and cave site. Turtle effigies. Petroform. site; effigies now destroyed (p. 436). Late Prehistoric but not including rock art, and Protohistoric but not including rock art. Plains Village association. : 107, 202, 382, 383, 388, 389, 391, 433, 436, 487, 494 Visited by Custer etc. in 1874 Black Hills Expedition; location is known.[18]

It's an Avonlea Complex site. "See The Archaeology of Ludlow Cave and Its Significance", by W. H. Over, American Antiquity Vol. 2, No. 2 (Oct., 1936), pp. 126–129 (6 pages) (at JSTOR). |

| 94000109 | 39HN5 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 93000805 | 39HN17 | Harding | 1993-08-06 | |

| 94000088 | 39HN18 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000124 | 39HN21 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000123 | 39HN22 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000122 | 39HN26 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000121 | 39HN30 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000119 | 39HN50 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000118 | 39HN53 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000120 | 39HN54 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000117 | 39HN121 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000114 | 39HN150 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000115 | 39HN155 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000116 | 39HN159 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000113 | 39HN160 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000091 | 39HN162 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000093 | 39HN165 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000092 | 39HN167 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000129 | 39HN168 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000128 | 39HN171 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000127 | 39HN174 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000126 | 39HN177 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000125 | 39HN198 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000110 | 39HN199 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000095 | 39HN205 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000094 | 39HN207 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 93000794 | 39HN208 | Harding | 1993-08-06 | |

| 94000107 | 39HN209 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000106 | 39HN210 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000105 | 39HN213 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000104 | 39HN217 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000103 | 39HN218 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000102 | 39HN219 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000111 | 39HN227 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000112 | 39HN228 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000101 | 39HN232 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000100 | 39HN234 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000098 | 39HN484 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000099 | 39HN485 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000097 | 39HN486 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 94000096 | 39HN487 | Harding | 1994-03-07 | |

| 82003930 | 39HN204 | Harding | 1982-08-02 | Lightning Spring site in Sandstone Buttes area, in vicinity of Ludlow, a Middle Archaic occupation site. A McKean site.: 143 Also a Late Archaic and/or Plains Woodland site.: 144

Late Archaic: 488 With Middle Archaic, Late Archaic, Plains Woodland (part of Woodland period?) and Late Prehistoric era artifacts. It is "a complex, stratified site with Middle Archaic through Late Prehistoric levels. Lightning Spring is a based camp with at least 12 episodes of use.": 152 a Pelican Lake Complex site.: 152 An Avonlea Complex site : 154 A Plains Village Pattern site.: 216 "The Lightning Spring site is a Middle Archaic base camp that provides indirect evidence of communal hunts. A series of distinct occupation layers contained pronghorn, bison, bighorn sheep, and canid bone, with pronghorn dominating. Researchers hypothesized that the large amount of pronghorn bone resulted from large-scale communal game drives (Keyser et al.1984; Keyser and Davis 1985). More direct evidence for Middle Archaic meat and hide procurement comes from 39HN108. This is recorded as a very extensive kill and butchering site assigned to the Hanna Complex. The site has not been excavated."[16]: 414 "Excavations intended to stabilize the rapidly eroding Lightning Spring site (39HN204) revealed 14 separate layers dating to the Middle and Late Archaic periods (Keyser 1985; Keyser and Davis 1984, 1985; Wettstaed et al. 1991). The site was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1983."[16]: 414 With some Middle Missouri Tradition Middle Missouri pottery McKean phase lithic technology including stone axes ("bifaces") found; Duncan points Duncan phase Duncan projectile points found.[19] |

| 93000765 | 39CO39 | Grand Mareau Corson |

1993-08-06 | Cairn and rock art site[16]: 379, 425, 427, 643 |

| 86002737 | 39ST55 | Stanley | 1986-08-14 | Antelope Creek Site Antelope Creek Site (39ST55) |

| 86002736 | 39ST230 | Stanley | 1986-08-14 | Bloody Hand Site Bloody Hand Site (39ST230) |

| 76001756 | Stanley | 1976-04-03 | Fort Pierre Chouteau Site, a U.S. National Historic Landmark | |

| 88000732 | 39ST217 | Stanley | 1988-08-15 | Fort Pierre II Fort Pierre II (39ST217) |

| 75002104 | 39JK84 | Jackson | 1975-06-11 | Lip's Camp, in White River Badlands, in vicinity of Wanblee. Historic Period Lakota site of "Early Reservation Period", was occupied 1880-1904 by the Wazhazha band of the Upper Brule Sioux[16]: 613, 617, 619 |

| 97000342 | Campbell | 1997-02-18 | Vanderbilt Archeological Site, a National Historic Landmark | |

| 93000795 | 39MP3 | McPherson | 1993-08-06 | Archeological Site No. 39MP3: rock art panel likely depicting bison heads[17] |

| 86000834 | 39WW203 | Walworth | 1986-04-03 | Gravel Pit Site Gravel Pit Site (39WW203), in vicinity of Mobridge |

| 93000799 | 39PO205 | Potter | 1993-08-06 | in vicinity of Gettysburg |

| 93000800 | 39PO63 | Potter | 1993-08-06 | in vicinity of Gettysburg |

| 03000504 | Sully | 2003-06-02 | Cooper Village Archeological Site, vic. of Onida | |

| 84003297 | 39HU66 | Hughes | 1984-02-23 | part of the Petroforms of South Dakota Thematic Resource (TR) |

| 84003307 | 39HU189 | Hughes | 1984-02-23 | part of the Petroforms of South Dakota TR |

| 84003308 | 39HU201 | Hughes | 1984-02-23 | part of the Petroforms of South Dakota TR |

| 66000715 | Hughes | 1966-10-15 | Arzberger site, a National Historic Landmark, on bluff above McClure Site | |

| 86002732 | 39HU7 | Hughes | 1986-08-14 | McClure Site (39HU7), part of Big Bend Area MRA |

| 86002739 | Hughes | 1986-08-14 | Cedar Islands Archeological District | |

| 86002741 | Hughes | 1986-08-14 | Fort George Creek Archeological District, part of the Big Bend Area MRA | |

| 86002740 | Hughes and Lyman | 1986-08-14 | Medicine Creek Archeological District, has 21 contributing sites including a village site | |

| 86002731 | 39HU52 | Hughes | 1986-08-14 | Old Fort Sully Site (39HU52) |

| 93000793 | 39HE331 | Hyde | 1993-08-06 | Archeological Site No. 39HE331, in vicinity of Holabird |

| 84003296 | 39HD22 | Hand | 1984-02-23 | in vicinity of Danforth |

| 66000710 | Buffalo | 1966-10-15 | Crow Creek Site, a National Historic Landmark relating to Crow Creek massacre | |

| 86002738 | Buffalo | 1986-08-14 | Fort Thompson Archeological District presumably in or near Fort Thompson, South Dakota Fort Thompson | |

| 66000711 | Buffalo | 1966-10-15 | Fort Thompson Mounds, a National Historic Landmark District, in or near Fort Thompson | |

| 03000505 | Buffalo | 2003-06-02 | Talking Crow Archeological Site, vic. of Fort Thompson | |

| 86002735 | 39LM207 | Lyman County | 1986-08-14 | Burnt Prairie Site (39LM207) Burnt Prairie Site, vic. of Lower Brule |

| 03000501 | Lyman | 2003-06-02 | Dinehart Village Archeological Site, vic. of Oacoma | |

| 90001940 | Lyman | 1990-12-31 | Fort Lookout IV, vic. of Oacoma | |

| 86002734 | 39LM208 | Lyman | 1986-08-14 | Jiggs Thompson Site (39LM208) Jiggs Thompson Site, vic. of Lower Brule |

| 03000502 | Lyman | 2003-06-02 | King Archaeological Site (Lyman County, South Dakota) King Archeological Site, vic. of Oacoma | |

| 66000717 | 39LM209 | Lyman | 1966-10-15 | Langdeau Site, vic. of Lower Brule. A National Historic Landmark |

| 05000588 | 39RO71 | Roberts | 2005-06-08 | Also known as Thunderbird Rock, in vic. of Sisseton |

| 84003408 | 39SP2 | Spink | 1984-02-01 | vic. of Frankfort |

| 05000590 | 39SP4 | Spink | 2005-06-08 | vic. of Tulare |

| 84003403 | 39SP12 | Spink | 1984-02-01 | vic. Ashton |

| 84003405 | 39SP19 | Spink | 1984-02-01 | vic. of Spink Colony |

| 84003411 | 39SP37 | Spink | 1984-02-01 | vic. of Crandon |

| 84003413 | 39SP46 | Spink | 1984-02-01 | vic. of Crandon |

| 93000802 | 39BE3 | Beadle | 1993-08-06 | vic. of Wolsey |

| 05000589 | 39BE2 | Beadle | 2005-06-08 | vic. of Wessington Springs |

| 84003199 | 39BE14 | Beadle | 1984-01-30 | vic. of Huron |

| 84003201 | 39BE15 | Beadle | 1984-01-30 | vic. of Huron |

| 84003206 | 39BE23 | Beadle | 1984-01-30 | vic. of Huron |

| 84003208 | 39BE46 | Beadle | 1984-01-30 | vic. of Huron |

| 84003210 | 39BE48 | Beadle | 1984-01-30 | vic. of Huron |

| 84003212 | 39BE57 | Beadle | 1984-01-30 | vic. of Yale |

| 84003215 | 39BE64 | Beadle | 1984-01-30 | vic. of Yale |

| 84003336 | 39JE10 | Jerauld | 1984-02-23 | vic. of Wessington Springs |

| 84003337 | 39JE11 | Jerauld | 1984-02-23 | vic. of Gann Valley |

| 84003384 | 39SB15 | Sanborn | 1984-02-01 | vic. of Mitchell |

| 84003397 | 39SB18 | Sanborn | 1984-02-01 | vic. of Forestburg |

| 84003399 | 39SB31 | Sanborn | 1984-02-01 | vic. of Forestburg |

| 66000712 | 39DV2 | Davison | 1966-10-15 | Mitchell Site, site of a prehistoric Mississippian culture village, open to the public. |

| 84003260 | 39DV24 | Davison | 1984-01-31 | vic. of Mitchell |

| 84003275 | 39DV9 | Davison | 1984-01-31 | vic. of Riverside |

| 66000714 | Hanson | 1966-10-15 | Bloom Site, a National Historic Landmark, vic. of Bloom | |

| 84003290 | 39HS48 | Hanson | 1984-03-15 | Fort James (South Dakota), vic. of Rosedale Colony |

| 84003292 | 39HS23 | Hanson | 1984-03-15 | Sheldon Reese Site, vic. of Mitchell |

| 84003294 | 39HS3 | Hanson | 1984-01-31 | vic. of Mitchell |

| 93000796 | 39MK12 | McCook | 1993-08-06 | vic. of Bridgewater |

| 01000664 | Minnehaha | 2001-06-14 | Brandon Village, vic. of Brandon | |

| 84003320 | 39HT14 | Lower James Hutchinson |

1984-01-31 | vic. of Olivet. Mound site of Plains Woodland period.[16]: 162, 455, 710, 712 |

| 84003323 | 39HT27 | Lower James Hutchinson |

1984-02-01 | Mound site of Plains Woodland period.[16]: 162, 455, 710, 713 |

| 84003325 | 39HT29 | Hutchinson | 1984-02-01 | vic. of Clayton. Mound site of Plains Woodland period.[16]: 162, 455, 710, 713 |

| 84003327 | 39HT30 aka 39HT202 | Hutchinson | 1984-02-01 | vic. of Clayton. Randall Phase site. Mound site of Plains Woodland period.[16]: 162, 189, 455, 710, 713 |

| 84003417 | 39TU5 | Turner | 1984-02-23 | At Turkey Ridge, vic. of Freeman. Petroform site, includes a thunderbird effigy "said to mark the campsite of a leader named Swan, according to Northern Cheyenne oral tradition" in 1750–1825 era.[16]: 429, 749–50 |

| 70000246 | Lincoln | 1970-08-29 | Blood Run Site, on the Iowa/South Dakota border along the Big Sioux River, a National Historic Landmark |

Natural history museums

- The Journey Museum, Rapid City

- The Mammoth Site Museum of Hot Springs, SD, Hot Springs

- Museum of Geology, South Dakota School of Mines & Technology, Rapid City

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Murray (1974), "South Dakota".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 McCarville, Bishop, Springer, and Scotchmoor (2005) "Paleontology and geology".

- ↑ Everhart (2005); "One Day in the Life of a Mosasaur".

- 1 2 3 Everhart (2005); "Where the Elasmosaurs Roamed".

- 1 2 Everhart (2005); "Other Times, Other Sharks".

- 1 2 3 Everhart (2005); "Turtles: Leatherback Giants".

- ↑ Weishampel, et al. (2004); "3.15 South Dakota, United States", pages 585-586.

- ↑ Lockley and Hunt (1999); "The Puzzle of Miocene Tracks in the Oligocene".

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "The High Plains: Thunder Birds, Water Monsters, and Buffalo-Calling Stones".

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Buffalo-Calling Stones".

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Archaeological Evidence of Ancient Fossil Collecting".

- ↑ Everhart (2005); "Our Discovery of the Western Interior Sea".

- ↑ SUE at the Field Museum "SUE's Discovery".

- ↑ SUE at the Field Museum "The Dispute Over SUE".

- ↑ SUE at the Field Museum "The Purchase of SUE".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 Linea Sundstrom April 2019. South Dakota State Plan for Archaeological Resources, 2018 Update (PDF). South Dakota State Historical Society.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Linea Sundstrom (February 25, 1993). "National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation: Prehistoric Rock Art of South Dakota MPS". National Park Service. Retrieved February 28, 2021. (with 11 rock art sketches) (from partly NPS-funded project directed by Linea Sundstrom)

- ↑ Waymarking site

- ↑ James D. Keyser; John L. Fagan (1993). "McKean Lithic Technology at Lightning Spring". Plains Anthropologist. 38 (145): 37–51. doi:10.1080/2052546.1993.11931644. JSTOR 25669181.

References

- Everhart, M. J. 2005. Oceans of Kansas - A Natural History of the Western Interior Sea. Indiana University Press, 320 pp.

- Lockley, Martin and Hunt, Adrian. Dinosaur Tracks of Western North America. Columbia University Press. 1999.

- Mayor, Adrienne. Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 0-691-11345-9.

- McCarville, Kata, Gale Bishop, Dale Springer, and Judy Scotchmoor. July 1, 2005. "South Dakota, US." The Paleontology Portal. Accessed September 21, 2012.

- Murray, Marian (1974). Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. p. 348. ISBN 9780020935506.

- "SUE's Journey: From Field to Field Museum." Sue at the Field Museum. Accessed 11/06/12.

- Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.