Majd al-Krum

| |

|---|---|

Local council (from 1963) | |

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • Also spelled | Majd al-Kurum (official) |

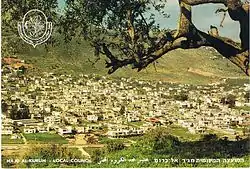

Majd al-Krum in the 1970s | |

Majd al-Krum  Majd al-Krum | |

| Coordinates: 32°55′14″N 35°15′10″E / 32.92056°N 35.25278°E | |

| Grid position | 173/258 PAL |

| Country | Israel |

| District | Northern |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5,400 dunams (5.4 km2 or 2.1 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)[1] | |

| • Total | 15,630 |

| • Density | 2,900/km2 (7,500/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | "Watch-house of the vineyard"[2] |

Majd al-Krum (Arabic: مَجْدُ الْكُرُوم, Hebrew: מַגְ'ד אל-כֻּרוּם Majd al-Kurum) is an Arab town located in the Galilee in Israel's Northern District about 16 kilometers (10 miles) east of Acre. Its inhabitants are primarily Muslim. In 2021 it had a population of 15,630.[1]

Name

The name Majd al-Krum translates from Arabic as "watch-house of the vineyard",[2] reflecting the town's fame for the quality of its grape vines,[3] and long history of growing grapes. Ancient ruins (located on the outskirts of the town), consisting of pits built into the rocks where the residents used their feet to press their grape crop to make wine.

Majd al-Krum has been suggested as being identical to Beit HaKerem (or Beth HaCerem), a Jewish Talmudic-period town mentioned in the Mishnah. Its Hebrew name means the same as its Arabic name.[4][5]

Geography

Majd al-Krum is an ancient site in the heart of the Galilee, situated in the northwestern end of the Beit HaKerem Valley, called al-Shaghur in Arabic, at the foot of Jabal Mahüz.[6][7] It is the largest Arab locality in the valley. It historically derived its importance from its position in the valley, which serves as the shortest and most accessible route between Acre in the west to the central Galilee, Safed, and Damascus to the east, and from its abundant spring.[8]

Archaeology

Ancient remains, including cisterns dug into the rock, have been found in Majd al-Krum.[6] In the center of Majd al-Krum, there is an ancient well, a spring, a Roman-era tomb and ruins dating to the Crusader period.[9]

History

Middle Ages

During the Crusader era, Majd al-Krum was known as Mergelcolon. It was part of Stephanie of Milly's inheritance.[10] Stephanie was the maternal grandmother of John Aleman, and in 1249 he transferred land, including Beit Jann, Sajur, Nahf and Majd al-Krum to the Teutonic Knights.[11]

Ottoman Empire

Incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517 with all of Palestine, Majd al-Krum appeared in the 1596 Ottoman tax registers as being in the nahiya (subdistrict) of Acre, part of the Safed Sanjak. It had a population of 85 households and five bachelors, all Muslims. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 25% on various agricultural products, including wheat, barley, olives or fruit trees, cotton, and goats and/or beehives; a total of 16,560 akçe.[12][13] The modern historian Oren Yiftachel, writing in the 1990s, noted that Majd al-Krum was "founded centuries ago by Muslim Arabs".[7]

During the period when the Zaydani family controlled the Galilee under their chief Zahir al-Umar (1730s–1770s), Majd al-Krum was a fortified village, with an unspecified number of towers built along its walls sometime during the same period. It was garrisoned by the local residents,[14] who were allied to the Zaydani family.[15] Oral accounts from Majd al-Krum maintain that the old mosque in the village and a cluster of homes around it date to this period.[15] Zahir was killed in his Acre headquarters by the Ottomans in 1775. When his Ottoman-appointed replacement, Jazzar Pasha, pursued Zahir's sons, who were holding out against the governor in their Galilee strongholds, the inhabitants of Majd al-Krum supported Zahir's son Ali.[15] The latter used Majd al-Krum and nearby Abu Sinan as his main strongholds, and launched raids against Acre, prompting Jazzar to mobilize his troops in the village of Amqa off the Mediterranean coast, north of Acre. Ali gathered the fighting men of Majd al-Krum, along with Abu Sinan and Deir Hanna, and besieged Jazzar's camp. Reinforcements from Acre dispersed Ali and his men, and defeated them at Abu Sinan. Jazzar himself then took lead of the army and led the assault on Majd al-Krum.[14] According to the historian Adel Manna, the fighting took place on the plain outside of the village, and Jazzar was victorious.[15] Once Majd al-Krum had fallen, Jazzar executed its defenders and sent their decapitated heads to the imperial capital at Constantinople as evidence of his success. He then proceeded against Ali, who had relocated his base to nearby Rameh.[14]

A map from Napoleon's invasion of 1799 by Pierre Jacotin showed the place, named as El Megd El Kouroum.[16] In 1838, Majd al-Krum was noted as a Muslim village in the Shaghur subdistrict, which was located between Safed, Acre and Tiberias.[17] In 1875, the French explorer Victor Guérin visited and described Majd al-Krum as being divided into three quarters, each with a different sheikh. The total population was 800 Muslims,[18] In 1881, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine described it as a village built of stone and surrounded by olive trees and arable land, inhabited by 600–800 Muslims.[19] A population list from about 1887 showed that Majd al-Krum had 1,075 inhabitants, all Muslims.[20]

British Mandate

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Majd al-Krum had a population of 889, of which 885 were Sunni Muslim, three Shia Muslims and one Christian.[21] In the 1931 census, Majd al-Krum had 226 occupied houses and a population of 1,006 Muslims.[22] In the 1945 statistics, Majd al-Kurum had 1,400 inhabitants, all Muslims.[23] They owned a total of 17,828 dunams of land, while 2214 dunams were public property.[24]

During the 1936–1939 Arab revolt against British Mandatory rule and increased Jewish settlement in Palestine, Majd al-Krum was one of the first villages in the Galilee to participate in the revolt with a resident, Abu Faris, claiming he was the first individual to take up arms in the Galilee during the revolt and the first to have his house demolished by the British as punishment for his participation. Abu Faris became the second-in-command of the revolt in the Galilee until 1938 when he refused an order to assassinate a Palestinian Arab supporter of the Peel Commission partition plan for Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. Abu Faris later left Palestine for Lebanon after a major political leader of the revolt, Amin al-Husayni, ordered his assassination.[25]

Israel

1948 Arab–Israeli War

Majd al-Krum was captured by Israeli forces in October 1948 during Operation Hiram. A unit of the Arab Liberation Army (ALA) that had been stationed there withdrew from the village upon the Israelis' approach. As he was departing, the ALA's Iraqi commander assembled the inhabitants around the village well and suggested that they not flee the village, but rather stay and surrender to Israeli officers that they knew. Accordingly, a group of Majd al-Krum's residents contacted Haim Auerbach, an Israeli intelligence officer based in Nahariya (who a group of villagers had previously defended from an attack near Acre). Auerbach arranged for Majd al-Krum's surrender and pledged no harm would come to the village.[26]

However, on 6 November, an Israeli Army unit, unaware of the village's surrender, entered the village and confronted the other Israeli unit already present in the village. The two sides realized their mistake after a brief exchange of fire, and the latter unit was replaced by the incoming unit. The new unit ordered the residents to hand over their weapons within 30 minutes despite having already surrendered their arms a week prior. Before the deadline was reached, the commanding Israeli officer ordered the demolition of a home and gathered five residents, blindfolded them and executed them by gunfire to demonstrate their seriousness. They gathered another five residents to execute but were stopped by a known Palestinian Arab informant from Damun, Shafiq Buqa'i. Buqa'i requested the Israeli officers free the residents by explaining to them the earlier agreement made between the villagers and Auerbach.[26]

During the 1948 War, the village of Sha'ab was largely depopulated and most of its residents settled in Majd al-Krum, some permanently and others temporarily.[27] Many people who fled Majd al-Krum settled in the Shatila refugee camp in Lebanon.[28] A former fighter from the village, Abed Bishr, leased a small plot of land outside Beirut and founded the Shatila refugee camp and gathered other refugees from Majd al-Krum to settle there. According to historian Julie Peteet, the role of Majd al-Krum and its refugees "was foundational in its [the camp's] establishment."[29] According to Yiftachel, Majd al-Krum "experienced tremendous upheaval" during the 1948 war, with about half of its inhabitants becoming refugees in Lebanon while becoming home to about 300 people from nearby villages,[7] mainly Sha'ab, Damun and Birwa.[30]

Land expropriation

Prior to the 1948 war, Majd al-Krum's land area consisted of 20,065 dunams (20.07 hectares), 69% of which was expropriated by the Israeli state between 1948 and the mid-1970s.[31] The majority of the land was expropriated on the basis of 1949 Absentees' Property Law from refugees who fled during the war, the remainder for "public purposes" or on the basis of lacking formal title (communal land as designated by Ottoman-era land laws).[31]

Jurisdiction over expropriated lands subsequently came under the Israel Land Authority (ILA), which, because of a 1960 law prohibiting the sale of state lands, began a process of land exchange with Majd al-Krum's remaining inhabitants.[32] Accordingly, many residents of Majd al-Krum exchanged agricultural land they owned for expropriated land within the village proper, i.e. areas designated for residential use, in lieu of purchasing lands expropriated from the village.[32] The typical exchange rate entailed the residents' transfer of five dunams of their agricultural lands for one dunam of land within the residential areas of the village, and the ILA would normally keep a 10–25% ownership stake in the residential parcel.[32] The ILA minority ownership stake was not explicitly marked in surveys, thus guaranteeing the ILA control over the residents' right to build on their newly acquired parcels.[32] The process of land exchange was particularly active between 1965 and 1980, during which 15,860 dunams were transferred to the ILA in exchange for 3,010 dunams transferred to Majd al-Krum's residents.[33]

In 1964 about 5,100 dunams of land were expropriated by the state for the construction of the Jewish town of Karmiel, whose establishment was declared as an effort to Judaize the Galilee by Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol.[34] In 1966, efforts for a master plan began and were completed in 1978. However, the master plan was not approved by the authorities and while the population grew from 4,000 to 6,700 between 1966 and 1990, no new land was allocated to Majd al-Krum to cope with population growth.[35] Beginning in the 1970s, the Jewish Agency launched efforts to build around sixty small Jewish communities, then known as mitzpim (observation points), in between Arab villages in the Galilee to monitor and check Arab building activity.[34] Among these Jewish communities were Lavon, Tuval, Gilon and Tzurit, which all border Majd al-Krum.[34]

Several hundred residents of Majd al-Krum took part in the Land Day demonstrations of 1976, which protested another round of the state's expropriation of Arab-owned land, in which 2,100 dunams from Majd al-Krum were transferred to expand Karmiel.[36] Six Arab protesters were killed in nearby Arab towns and since then, mass expropriation of Arab-owned land by the state has virtually ended.[36]

From the late 1970s

In 1977, large anti-government demonstrations were held in Majd al-Krum and nearby villages to protest the demolition of a house in Majd al-Krum built near the road between Safed and Acre. One person was killed and several others injured as police attempted to disperse protesters. The incident prompted mayor Muhammad Manna to leave the Labor Party and join Hadash. Manna was subsequently reelected in 1986.[37] Tawfiq Ziad, a member of the Knesset, declared "as long as there are stones in the Galilee, we shall use them to stone those who try to destroy our homes."[38] The protest and the response of the state led to more assertive opposition by Israel's Arab community toward state policies.[37]

During the 2006 Lebanon War, over 40 Katyusha rockets landed in the vicinity of Shaghur, with the nearby city of Karmiel being the apparent target. Two men from Majd al-Krum, Baha' Karim and Muhammad Subhi Mana', were killed when a rocket struck near them.[39]

Local government

Majd al-Krum was declared a local council in 1963.[7] Members of the council are elected and the council is responsible for basic municipal services, although local planning has remained in the jurisdiction of the Central Galilee Local Planning Committee appointed by the central government of Israel.[40] In 2003 Majd al-Krum and the nearby local councils of Deir al-Asad and Bi'ina merged to form the city of Shaghur.[41] Shaghur was dissolved in 2009.[42]

Economy

The headquarters of Moona, an NGO that works to integrate Israeli Arabs into the high tech industry, are located in Majd al-Krum.[43]

Transportation

Israel Railways has proposed building an additional train station at Majd al-Krum on the Railway to Karmiel, although the dates for construction are not set.[44]

Notable people

- Adel Manna, historian and writer

- Ahmad Saba'a, former footballer

- Dia Saba, footballer, Israel national football team

- Haytham Dheeb, Footballer, Palestine national football team

- Mohammed Kna'an, footballer, Israel national football team

References

- 1 2 "Regional Statistics". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- 1 2 Palmer, 1881, p. 52

- ↑ Asser, Martin. Inside a Palestinian refugee camp. BBC News. 2008-05-17.

- ↑ Avi-Yonah, Michael (1976). "Gazetteer of Roman Palestine". Qedem. 5: 38. ISSN 0333-5844.

- ↑ בקעת בית כרם [Beit-Kerem Valley]. Jewish Encyclopedia Daat (in Hebrew). Herzog College.

- 1 2 Dauphin, 1998, p. 662.

- 1 2 3 4 Yiftachel 1998, p. 53.

- ↑ Haidar 1995, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Jacobs, p. 240.

- ↑ RHC Lois II, 1843, p. 454; cited in Frankel, 1988, p. 253.

- ↑ Strehlke, 1869, pp. 78–79, No. 100; cited in Röhricht, 1893, RHH, p.308, No. 1175; cited in Frankel, 1988, p. 254.

- ↑ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 191.

- ↑ Note that Rhode, 1979, p. 6 writes that the register that Hütteroth and Abdulfattah studied was not from 1595/6, but from 1548/9.

- 1 2 3 Cohen 1973, p. 94.

- 1 2 3 4 Manna 2007, p. 74, note 20.

- ↑ Karmon, 1960, p. 166.

- ↑ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 3, 2nd appendix, p. 133

- ↑ Guérin, 1880, pp. 437-438, 444

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 150.

- ↑ Schumacher, 1888, p. 173

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Acre, p. 36

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 101

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 4

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 40

- ↑ Swedenburg, 2003, pp. 164–165.

- 1 2 Cohen, 2010, pp. 105–106.

- ↑ Cohen, 2010, p. 100.

- ↑ Peteet, 2011, pp. 113-114.

- ↑ Peteet, 2011, p. 114.

- ↑ Manna 2007, p. 69.

- 1 2 Yiftachel 1995, p. 140.

- 1 2 3 4 Yiftachel 1995, p. 141.

- ↑ Yiftachel 1995, p. 142.

- 1 2 3 Yiftachel, 1995, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ McDowall, p. 138.

- 1 2 Yiftachel, p. 152.

- 1 2 Reiter, p. 79.

- ↑ Reiter, p. 82.

- ↑ Civilians under assault, Case Studies: Karmiel, Majd al-Kurum and Deir al-Assad Human Rights Watch. August 2007.

- ↑ Yiftachel 1998, pp. 53, 60.

- ↑ Gutterman, Dov. Local Council of Majd el-Kurum (Israel). Flags of the World.

- ↑ Table 1 - Population of Localities Numbering Above 2,500 Residents. Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (ICBS). 2009.

- ↑ "Moona brings high-tech centers to Israel's Arab communities". The Jerusalem Post. 1 October 2021. Archived from the original on 26 November 2023. Retrieved 26 November 2023.

- ↑ "Karmiel - Akko railway line completed". Globes. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Beugnot, Comte de, ed. (1843). RHC Lois II (in French and Latin). Paris: R.H.C.

- Cohen, Amnon (1973). Palestine in the 18th Century: Patterns of Government and Administration. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press.

- Cohen, Hillel (2010). Good Arabs: The Israeli Security Agencies and the Israeli Arabs, 1948-1967. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520944886.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, C. (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). Vol. III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Frankel, Rafael (1988). "Topographical notes on the territory of Acre in the Crusader period". Israel Exploration Journal. 38 (4): 249–272.

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Haidar, Aziz (1995). On the Margins: The Arab Population in the Israeli Economy. London: Hurst and Company. ISBN 978-1-8506-5174-1.

- Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 3: Galilee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253.

- Manna, A. (Spring 2007). "From Seferberlik to the Nakba: A Personal Account of the Life of Zahra al-Ja'uniyya". Jerusalem Quarterly. 30: 59–76.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Peteet, Julie (2011). Landscape of Hope and Despair: Palestinian Refugee Camps. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812200317.

- Rhode, H. (1979). Administration and Population of the Sancak of Safed in the Sixteenth Century (PhD). Columbia University.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Reiter, Y. (2009). National Minority, Regional Majority: Palestinian Arabs Versus Jews in Israel. New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-3230-6.

- Röhricht, R. (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Strehlke, Ernst, ed. (1869). Tabulae Ordinis Theutonici ex tabularii regii Berolinensis codice potissimum. Berlin: Weidmanns.

- Swedenburg, Ted (2003). Memories of Revolt: The 1936–1939 Rebellion and the Palestinian National Past. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1610752635.

- Yiftachel, O. (1995). "The Planning of Majd el Krum: The Practice of Control". Progress in Planning. 44 (2): 139–158. doi:10.1016/0305-9006(95)90165-5. ISSN 0305-9006. Archived from the original on 2016-04-09. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

- Yiftachel, O. (1998). "The Internal Frontier: Territorial Control and Ethnic Relations in Israel". In Yiftachel, O.; Meir, Avinoam (eds.). Ethnic Frontiers and Peripheries: Landscapes of Development and Inequality in Israel. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-8929-1.

External links

- Majd al-Krum municipal website

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 3: IAA, Wikimedia commons

.svg.png.webp)