| Industry | Glass manufacturing |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1887 |

| Founder | Leopold Mambourg, Charles Foster |

| Defunct | 1893 |

| Headquarters | |

Key people | Leopold Mambourg, Charles Foster |

| Products | window glass |

Number of employees | 60 (1888) |

Mambourg Glass Company was a window glass manufacturer that began production on October 26, 1887. The company was the first of thirteen glass manufacturers located in Fostoria, Ohio, in the United States, during northwest Ohio's gas boom. The plant was managed by Leopold Mambourg, a Belgian immigrant and experienced glassmaker. Much of the company's work force was also from Belgium. Former Ohio governor Charles Foster was president of the company and a major financial backer. He was also a major investor in other businesses and two additional Fostoria window glass companies: the Calcine Glass Company and the Crocker Glass Company. Mambourg was the chief operating officer for all three of Foster's window glass companies.

The startup for Mambourg Glass Company went well, and the company was busy producing high quality window glass. A capacity expansion was finished in January 1890. The company continued to hire glassworkers from Belgium to meet its need for more skilled workers. By mid-1891 the plant, and other factories in Fostoria, was plagued by fuel shortages as northwest Ohio's natural gas that was used to power the glass company furnaces began to be depleted.

In the summer of 1892, Leopold Mambourg left town to start another glass company near Columbus, Ohio. During the Panic of 1893 Foster could no longer meet his financial obligations. In May his three window glass companies were closed and Foster assigned control of the three companies (and others) to his creditors. The Mambourg Glass Company plant was leased from the creditors and restarted in December 1893 as an employee-owned co-op. However, after it closed for the summer stop on June 19, 1894, it never reopened.

Background

Window glassmaking in the 1880s

Glass is made by starting with a batch of ingredients (mostly sand), melting it, forming the glass product, and gradually cooling it.[Note 1] The batch is placed inside a pot or tank that is heated by a furnace to roughly 3090 °F (1700 °C).[1] During the 1880s, window glass was made using the hand–blown cylinder glass method.[3] A crew led by a glassblower started the process of shaping the glass. A gatherer removed a glob of molten glass (called a gob) from the furnace using a blowpipe.[4] The blowpipe, with its gob, was then passed to a glassblower, who would blow into the pipe to start the creation of a hollow cylinder. The glassblower would enlarge the cylinder, sometimes with the assistance of a wooden mold.[3] Periodically the glassblower would reheat the cylinder to keep it elastic. The reheating was done at a section of the furnace called the glory hole, which was a small hole in the side of the furnace that was often at right angles to the main gathering hole.[5] A typical cylinder was up to five feet (1.5 m) long.[6] The cylinder was cooled and then cut at both ends (the "caps") by a craftsman called a cutter.[6] The cylinder, now a tube, was then cut lengthwise to prepare it for flattening.[7]

Glass products must be cooled gradually (annealed), or else they can become brittle and possibly break.[8] A long conveyor oven used for annealing is called a lehr.[9] In the case of window glass, a combination flattening oven and lehr could be used.[10] The glass tube was placed in the oven with the slit side up. Workers known as flatteners make sure the reheated cylinder unfolds into a flat sheet.[7] After the flat glass has moved from the hot end of the oven to the cool end, which can take hours, it is inspected, cut to the desired size, and packed.[11] The size of each piece of window glass varied, but was limited by the size of the cylinder. Statistics for unpolished window glass imported into the United States in 1880 show that about half of the tonnage consisted of glass above 10 inches (25 cm) by 15 inches (38 cm) in size and below 24 inches (61 cm) by 30 inches (76 cm).[12]

Most glass factories had a summer stop where the production was shut down for about six weeks.[13] This was done because the summer heat combined with the heat of the furnace to make the work environment almost unbearable for workers in the hot end (near molten glass). The summer stop also allowed time to perform maintenance on the facility without disrupting the production process.[13] Window glass workers spent more time adjacent to furnaces and ovens because they reheated their product, so some companies had summer stops that lasted from the beginning of May until the end of August.[6]

Because most glass plants melted their batch in a pot during the 1880s, the plant's number of pots was often used to describe a plant's capacity. The ceramic pots were located inside the furnace, and contained molten glass created by melting the batch of ingredients.[14] Tank furnaces, which were less common than pots in the 1880s, were essentially large brick pot furnaces with multiple workstations. A tank furnace is more efficient than a pot furnace, but more costly to build.[15] One of the major expenses for the glass factories is fuel for the furnace.[16] Wood and coal had long been used as fuel for glassmaking. An alternative fuel, natural gas, became a desirable fuel for making glass in the late 19th century because it is clean, gives a uniform heat, is easier to control, and melts the batch of ingredients faster.[17]

Belgian glassmakers

During the 1880s, Belgium was known for its window glass manufacturing, and about two thirds of the window glass it made was exported.[18] The window glass workers were skilled as glassblowers, gatherers, flatteners, and cutters—and these skills were learned in long apprenticeships.[19] Many of its window glass works, over 130 operating furnaces, were located in Charleroi, which is not far from the border with France.[20] In 1886, approximately 30 percent of the Belgian glassworkers were unemployed because of strikes and a recession.[21]

In America, natural gas was discovered in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana during the 1880s and 1890s—causing economic "gas booms". Politicians and businessmen in these American communities took advantage of the newfound fuel source to entice manufacturers, including glass makers, to locate their plants near the low–cost fuel sources. The glass manufacturers also needed skilled labor for their plants.[22] Thus, the American window glass plants needed skilled labor, and a good supply of skilled labor was available in Belgium. The Belgian window glass workers that came to America around this time made their product using the hand–blown cylinder method.[19][Note 2] Among the Belgian glass workers that came to America was Leopold Mambourg (1860–1929), who started his American career at Pittsburg Plate Glass Company.[25]

Ohio glass industry

In the 1870s Ohio had a glass industry located principally in the eastern portion of the state, especially in coal-rich Belmont County. The Belmont County community of Bellaire, located on the Ohio side of the Ohio River across from Wheeling, West Virginia, was known as "Glass City" from 1870 to 1885.[26] In early 1886, a major discovery of natural gas (the Karg Well) occurred in northwest Ohio near the small village of Findlay.[27] Communities in northwestern Ohio began using low-cost natural gas along with free land and cash to entice manufacturing companies (especially glass makers) to start operations in their towns.[28] The enticement efforts were successful, and at least 70 glass factories existed in northwest Ohio between 1886 and the early 20th century.[29]

The city of Fostoria, already blessed with multiple railroad lines, was close enough to the natural gas that it was able to use a pipeline to make natural gas available to businesses.[30] Eventually, Fostoria had 13 different glass companies at various times between 1887 and 1920.[31][Note 3] The gas boom in northwestern Ohio enabled the state to improve its national ranking as a manufacturer of glass (based on value of product) from 4th in 1880 to 2nd in 1890.[34] However, northwestern Ohio had serious problems with its gas supply by 1891, and the glass industry had over–expanded.[35][Note 4] Some local companies, such as Fostoria Glass Company, decided to move elsewhere to be near better fuel supplies.[36]

Early years

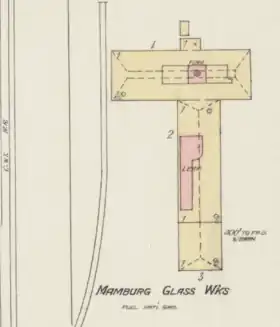

The Mambourg Glass Company was incorporated in Ohio during August 1887 with capital stock of $25,000.[37] Charles Foster was named company president, and J. E. Wilkison became secretary and treasurer. Those two officers were also directors, as were Leopold Mambourg, J. J. Bastin, and B. B. Barry.[38] Ground had already been broken for the new glass works on July 20, 1887, and construction began in mid–August.[39] The new glass works would have a 13 pot furnace.[40][Note 5] Mambourg (the company's namesake) was the company's general manager, and he supervised the plant's construction—Fostoria's first glass works.[43] Although Fostoria Glass Company was incorporated before Mambourg Glass Company, it did not start construction of its plant until September 12, 1887—and it did not start production until almost two months after the Mambourg Glass startup.[44]

Production was ready to start on the evening of October 25, although it did not actually start until after midnight (October 26). It took another week before production was made at full capacity.[40] A state inspection report later noted that the glass works had 60 male employees and access to the Columbus and Toledo Railroad.[45] The window glass produced was such good quality that the company received more orders than it could handle, causing some orders to be refused.[40] Management soon decided it needed to increase capacity, and work began to accomplish that objective on August 1, 1888, after the beginning of the summer stop.[46]

In addition to managing this plant, Mambourg was also managing two other window glass plants controlled by Foster. Mambourg, Foster, and others started the Calcine Glass Company in August 1888.[47] Later in 1888, the Crocker Glass Company was started by Foster, Rawson Crocker (Foster's brother–in–law), and others. Mambourg managed all three companies.[43] The expansion work at the Mambourg Glass works was completed in late January 1890.[48] The plant expansion included a new tank furnace, flattening ovens, and an additional building.[49][Note 6] The expansion caused a need for more skilled glassworkers during a time when there was a shortage of that type of talent, so more experienced workers were hired from Belgium.[51]

Decline

The U.S. economy suffered through multiple recessions during the late 1880s and 1890s, making life difficult for manufacturing firms. The U.S. business cycle peaked during July 1890, and declined until May 1891.[52] Leopold Mambourg was managing three glass companies and facing the difficulty of Fostoria's natural gas shortages. Recessions plus periodic shutdowns caused by the fuel shortages caused all three window glass plants to have financial problems. To help the over–taxed Leopold Mambourg, management hired T. T. Lewis to manage daily operations at the three glass plants. In the summer of 1892, Mambourg left town to establish a new glass plant in Circleville, Ohio (near Columbus).[48]

An economic depression began in January 1893 and became known as the Panic of 1893, bringing deflation and a high unemployment to the nation.[53] In May the nation was shocked when Foster, who had recently completed his term as U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, failed financially and assigned control of his financial interests to his creditors.[54] The three window glass companies where Foster was a major investor (Mambourg Glass Company, Crocker Glass Company, and Calcine Glass Company) shut down and some banks and non-glass companies were also affected.[55] During the autumn, a group of former employees received permission from Foster's creditors to reopen the plant as an employee–owned co–op. Capital was raised and the plant was leased from the creditors.[56] Production started in December 1893.[57] After the June 19, 1894, summer stop, the plant did not reopen.[58]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ The batch of ingredients is dominated by sand, which contains silica.[1] Other ingredients such as soda ash, potash, and either red lead or lime are added.[2]

- ↑ Glassblowers and gatherers used in the window glassmaking process were made obsolete during the early 1900s by the Lubbers machine.[23] During the 1920s, the window glass making process changed dramatically because of inventions by Michael Owens, Pittsburgh Plate Glass, and a European method known as the Fourcault process.[24]

- ↑ The count of Fostoria glass companies varies depending on how restarts and reorganizations are counted. The Fostoria Ohio Glass Association lists 13 companies for 1887-1920.[32] Paquette discusses 15 companies plus four post-boom companies in Chapter V of his Blowpipes book.[33]

- ↑ Paquette notes that the pressure in gas wells was trending lower by late 1888, especially during the cold winters of 1888 and 1889. By early 1890, gas flow to factories was occasionally restricted and sometimes shut off completely.[29]

- ↑ Paquette's source for the furnace size of 13 pots is the September 1, 1887, edition of the Tiffin Daily Tribune.[41] An 1890 report by the state geologist says the plant had a 10 pot furnace.[42]

- ↑ Paquette's source for the plant expansion details is the December 19, 1889, edition of the Fostoria Review.[50]

Citations

- 1 2 "How Glass is Made - What is glass made of? The wonders of glass all come down to melting sand". Corning. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ↑ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 30

- 1 2 Kutilek 2019, p. 38

- ↑ Kutilek 2019, p. 38; Shotwell 2002, p. 219

- ↑ Kutilek 2019, p. 39; Shotwell 2002, p. 219

- 1 2 3 Kutilek 2019, p. 39

- 1 2 Kutilek 2019, p. 40; Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 50

- ↑ "Corning Museum of Glass - Annealing Glass". Corning Museum of Glass. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ↑ "Corning Museum of Glass - Lehr". Corning Museum of Glass. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ↑ Unknown 1906, p. 400

- ↑ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 50

- ↑ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, pp. 100–101

- 1 2 Shotwell 2002, p. 542

- ↑ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 35; Shotwell 2002, p. 440

- ↑ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 61

- ↑ United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce 1917, p. 12

- ↑ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 36

- ↑ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 73

- 1 2 Fones–Wolf 2002, p. 61

- ↑ Weeks & United States Census Office 1884, p. 74

- ↑ Fones–Wolf 2002, p. 64

- ↑ Fones–Wolf 2002, p. 67

- ↑ Fones–Wolf 2002, p. 70

- ↑ Chandler & Hikino 1990, pp. 115–116

- ↑ "Leopold Mambourg, Local Glass Manufacturer, Dies". Lancaster Eagle–Gazette (Ancestry). June 14, 1929. p. 1.

The deceased was nationally known as an authority on glass manufacture and was in great measure responsible for the development of the industry here.

- ↑ McKelvey 1903, p. 170

- ↑ Paquette 2002, pp. 24–25; Skrabec 2007, p. 25

- ↑ Paquette 2002, p. 26; Skrabec 2007, pp. 23–26

- 1 2 Paquette 2002, p. 28

- ↑ H. Sabine, Commissioner of Rail Roads & Telegraphs (1882). New Rail Road Map of Ohio prepared by H. Sabine, Commissioner of Rail Roads & Telegraphs (Map). Wapakoneta, Ohio: R. Sutton (Library of Congress). Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved August 5, 2023.; Paquette 2002, p. 173; Geological Survey of Ohio, Robinson & Orton 1890, p. 190

- ↑ "Fostoria Ohio Glass Association". Fostoria Ohio Glass Association. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Fostoria Ohio Glass Association". Fostoria Ohio Glass Association. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ↑ Paquette 2002, pp. 10–11 TOC

- ↑ United States Census Office 1895, p. 315

- ↑ Skrabec 2007, p. 55

- ↑ Paquette 2002, pp. 179–183; "About People - Daily Chronicle of the Movement of Individuals". Daily Register (Wheeling). January 12, 1892. p. 5.

W.S. Brady, of the Fostoria Glass Company, of Moundsville.... We will start up next Monday.

- ↑ "Incorporations". Cincinnati Commercial Gazette (NewspaperArchive). August 12, 1887. p. 4.

The Mambourg Glass Company, Fostoria, capital stock $25,000.

- ↑ "Fostoria's Glass Company". Cincinnati Commercial Gazette (NewspaperArchive). August 19, 1887. p. 5.

The Mambourg Glass Company, which recently located a window–glass factory in Fostoria, this afternoon elected the following officers....

- ↑ Paquette 2002, pp. 179–183

- 1 2 3 Paquette 2002, p. 176

- ↑ Paquette 2002, pp. 176, 496

- ↑ Geological Survey of Ohio, Robinson & Orton 1890, p. 191

- 1 2 Paquette 2002, p. 175

- ↑ Paquette 2002, p. 243

- ↑ State of Ohio & Dorn (Chief State Inspector) 1889, p. 65

- ↑ Paquette 2002, pp. 176–177

- ↑ Paquette 2002, pp. 194–195

- 1 2 Paquette 2002, p. 178

- ↑ Paquette 2002, pp. 177–178

- ↑ Paquette 2002, pp. 177–178, 496

- ↑ Paquette 2002, p. 177

- ↑ "US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions". National Bureau of Economic Research. Archived from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved 2023-03-31.

- ↑ "The Depression of 1893". Economic History Association. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ↑ "Failure of Charles Foster (page 1 top center)". Indianapolis Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). May 27, 1893. Archived from the original on 2023-08-22. Retrieved 2023-08-22.; "Gave Up the Fight – Ex–Secretary Chas. Foster Fails (page 6, Other Concerns Fail)". Washington Evening Star (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). May 26, 1893. Archived from the original on 2023-09-26. Retrieved 2023-09-26.

- ↑ "Failure of Charles Foster (page 1 top center)". Indianapolis Journal (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). May 27, 1893. Archived from the original on 2023-08-22. Retrieved 2023-08-22.; "Gave Up the Fight – Ex–Secretary Chas. Foster Fails (page 6, Other Concerns Fail)". Washington Evening Star (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). May 26, 1893. Archived from the original on 2023-09-26. Retrieved 2023-09-26.; Paquette 2002, pp. 178, 193, 200–201

- ↑ Paquette 2002, pp. 178–179

- ↑ "Tickings of the Telegraph". Middleburgh Post (Snyder Co. PA) (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). December 14, 1893. Archived from the original on 2023-09-26. Retrieved 2023-09-26.

The Mambourg glass works, which has been idle for several months, has resumed, employing 75 men.

- ↑ Paquette 2002, p. 179

References

- Chandler, Alfred D.; Hikino, Takashi (1990). Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-67478-994-4. OCLC 20013290.

- Fones–Wolf, Ken (Winter 2002). "Immigrants, Labor and Capital in a Transnational Context: Belgian Glass Workers in America, 1880-1925". Journal of American Ethnic History. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press (JSTOR). 21 (2): 59–80. JSTOR 27502813. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- Geological Survey of Ohio; Robinson, S. W.; Orton, Edward (1890). First Annual Report of the Geological Survey of Ohio. Columbus, Ohio: Westbote Co., State Printers. OCLC 1026686144. Archived from the original on August 3, 2023. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- Kutilek, Luke (2019). "Flat Glass Manufacturing Before Float". In Sundaram, S. K. (ed.). 79th Conference on Glass Problems: A Collection of Papers Presented at the 79th Conference on Glass Problems, Greater Columbus Convention Center, Columbus, Ohio, November 4–8, 2018. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (issued by American Ceramic Society). pp. 37–54. ISBN 978-1-11963-155-2. OCLC 1099687444.

- McKelvey, Alexander T. (1903). Centennial History of Belmont county, Ohio and Representative Citizens. Chicago: Biographical Publishing Company. OCLC 318390043.

Centennial history of belmont county.

- Paquette, Jack K. (2002). Blowpipes, Northwest Ohio Glassmaking in the Gas Boom of the 1880s. Xlibris Corp. ISBN 1-4010-4790-4. OCLC 50932436.

- Shotwell, David J. (2002). Glass A to Z. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-0-87349-385-7. OCLC 440702171.

- Skrabec, Quentin R. (2007). Glass in Northwest Ohio. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-73855-111-1. OCLC 124093123.

- State of Ohio; Dorn (Chief State Inspector), Henry (1889). Fifth Annual Report of the Chief State Inspector of Workshops and Factories, to the General Assembly of the State of Ohio, for the year 1888. Columbus, Ohio: Office Chief State Inspector of Workshops and Factories (The Westbote Company, State Printers). OCLC 13049818. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- United States Census Office (1895). Report on manufacturing industries in the United States at the eleventh census: 1890. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 10470409.

- United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign and Domestic Commerce (1917). The Glass Industry. Report on the Cost of Production of Glass in the United States. Washington: Government Printing Office. OCLC 5705310.

- Unknown (December 1, 1906). "The First Machine for the Commercial Production of Window Glass by the Sheet Process". Scientific American. New York City: Munn and Company. XCV (22): 400, 403. OCLC 1775222. Archived from the original on September 26, 2023. Retrieved September 21, 2023.

- Weeks, Joseph D.; United States Census Office (1884). Report on the Manufacture of Glass. Washington, District of Columbia: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 2123984. Archived from the original on July 16, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2023.