Maria Dulębianka | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Born | 21 October 1861 |

| Died | 7 March 1919 (aged 57) |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Other names | Maria Dulembianka |

| Occupation(s) | artist, activist |

| Years active | 1881–1919 |

Maria Dulębianka (21 October 1861 – 7 March 1919) was a Polish artist and activist, notable for promoting women’s suffrage and higher education.

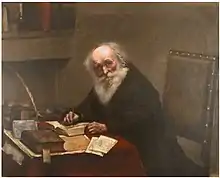

She studied art in Warsaw, Vienna and Paris, two of her works gaining distinctions in the 1900 Paris Exposition. Many of her paintings were portraits of her lifelong companion, the poet Maria Konopnicka. In 1908, Dulębianka stood for the Agrarian Party in the elections to the Galician Parliament, but was disallowed as a woman by parliamentary rules. When Polish women gained the vote in 1918, Dulębianka served as a delegate to the Provisional Government. She died of typhus, contracted while assisting prisoners in the Polish–Ukrainian War of 1919.

Early life

Maria Dulębianka was born on 21 October 1861 in Kraków, Grand Duchy of Kraków, Austrian Empire, to Maria of Wyczółkowscy and Henryk Dulęba.[1] Her family were landowning gentry[2] with her mother's family bearing the coat of arms of Ślepowron and her father's, the Alabanda coat of arms.[3] She attended the Maliszewska finishing school in Kraków and took private art lessons from Jan Matejko until 1872. Unable to gain admittance to the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts because she was a woman, Dulębianka went on to further her studies at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts,[1] where she studied with Leopold Horowitz.[1][4]

After two years, she moved first to Warsaw, where she trained with Wojciech Gerson,[1][4] and then in 1884 to Paris to train at the Académie Julian.[4][5] In Paris, she studied with William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Carolus-Duran, Jean-Jacques Henner, and Tony Robert-Fleury until 1886.[5][6] The majority of Dulębianka's paintings were portraits or scenes of women and children. After first exhibiting in Kraków, she participated in showings in Warsaw and later Paris.[1][4]

Career

Painting

In 1887, Dulębianka returned to Warsaw intent upon opening an art school for women.[6] A supporter of women's suffrage, she advocated for women to be admitted to the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts as early as 1885.[1] In 1889, she met Maria Konopnicka, a mother of eight children and a writer, who was living independently and separated from her husband, Jarosław Konopnicki. Dulębianka was almost 30 at the time,[3] and Konopnicka was 19 years her senior. The two became inseparable and from the time of their meeting, Konopnicka became the main subject of Dulębianka's paintings.[3][4] The nature of their relationship has not been conclusively settled by academics,[2][7][8][Notes 1][9] in part because after their deaths letters were burned by family members,[8] but also because Konopnicka was aware official censors might read her correspondence and rarely wrote about family matters even in her published works.[4][7] Krzysztof Tomasik, who wrote about Dulębianka in Homobiografie (2008), confirmed that she had had other relationships with women and that the couple had friends who were known lesbians, though the term was not in use at the time.[10][Notes 2]

Konopnicka became a strong influence on Dulębianka, who increasingly became involved in social welfare projects and activism for women's rights.[3] In 1890, the couple left Warsaw and began traveling. They visited Germany, Italy, France, and health resorts in Austria and the Czech regions of Austria-Hungary, rarely returning to Poland.[3][16] They traveled by bicycle and Dulębianka attracted attention for her manner of dressing. She shunned women's attire, instead wearing trousers or a long, straight skirt; cuffed-shirts and ties; a frock coat; and flat-heeled shoes. She also cut her hair short and always wore a monocle or pince-nez glasses.[3][4][17] Konopnicka called Dulębianka Piotrek or Pietrek and wrote to her children of their adventures, always referring to things "we" did, rather than "I" did.[3][4]

Wherever they were living, Konopnicka made sure that Dulębianka had a studio to enable her to continue painting.[3] She presented her works at exhibitions and participated in events in Dresden, Kyiv, London, Lviv, Munich, Paris and Prague.[6] In 1900, at the Paris Exposition, two of her paintings — Na pokucie (On Penance) and Sieroca dola (The Orphan's Fate) — were honored with distinction and a third, Studium dziewczyny (Girls' Studio) was purchased, while still on display, by the National Museum in Kraków.[1][17]

Activism

In 1897, Dulębianka joined the Emancipation Center in Lviv and successfully pressed the city to establish a women's high school, enabling girls to access higher education.[1][4] She published articles on women's issues in the feminist journal Ster[4] (The Rudder) and worked as an editor for Głos Kobiet (Women's Voice) and the Kurier Lwowski (Lviv Courier).[3] In 1901, Dulębianka gave a lecture in Zakopane called Dlaczego ruch kobiecy rozwija się tak powoli? (Why is the Women's Movement Developing so Slowly?). The following year, she gave a talk about women's artistic activity and in 1903 published the article O twórczości kobiet (About Women's Creativity) in Głos Kobiet.[1] Dulembianka fought for the admission of women to the ranks of the students of the Kraków School of Fine Arts and for the creation of a female gymnasium in Lviv. She was also regularly published in the feminist magazine "Ster", published by Paulina Kuchalska-Reinschmidt.[18]

In 1902, Konopnicka's 25-year career as a writer was celebrated and as the highest honor that could be bestowed at the time, she was given a home in Żarnowiec as a national gift. From 1903, she and Dulębianka spent their springs and summers at the manor house, but continued to travel the rest of the year.[16][19] Dulębianka began campaigning for women to gain the right to vote in Galicia in 1907.[2] She emphasized the absence of political rights for women at the Warsaw Philharmonic,[17] explaining that women had only the power of attorney, but no real active or passive rights.[20] The following year, she campaigned as a candidate of the Agrarian Party for the Galician Parliament.[2][20] Supported by the People's Election Committee and the Progressive Women's Education Club, she launched her campaign with a pre-election speech on the ideal of equality.[1][4][17] Her booklet, Polityczne stanowisko kobiety (Woman's Political Stance), criticized political parties for ignoring women and pandering to the whims of public opinion, whipping up support with class and nationalist agendas.[21] Though she received 511 votes from male voters, her name was struck from the voting list because women were not eligible to serve in Parliament and her supporters' votes were nullified.[1][3][20]

In 1909, Dulębianka spoke on behalf of the Stronnictwo Jutra (Party of Tomorrow), outlining a platform which demanded social equality, Polish independence, and the cooperation of Poles and Ukrainians.[3][17] When Konopnicka's health began to fail in 1910, the couple moved permanently to Lviv, where they could gain treatment for her at the Kisielki Sanatorium.[1][17] Konopnicka, Dulębianka's companion for two decades, died on 8 October 1910 and Dulębianka organized a funeral which was attended by thousands of mourners.[3][17] In 1911, she founded the Women's Electoral Committee to press for women's inclusion in the Lviv City Council[21] and spoke out about the annexation of Chełmszczyzna by the Russian Empire.[17]

Continuing her work to secure rights and help the poor, Dulębianka founded the Związek Uprawnienia Kobiet (Union of Women's Rights), the Liga Mężczyzn dla Obrony Praw Kobiet (Men's League for the Defense of Women's Rights) and the Komitet Obywatelskiej Pracy Kobiet (Women's Civic Work Committee).[1] Leading the Civic Work Committee, she established kitchens for the poor, children's nurseries and Klub Uliczników (Street Children's Club), providing help for street children and orphans.[1][17] When the Rifle Association was formed in Lviv, Dulębianka balked at custom and became one of its first members.[17] In 1914, she urged Civic Work members to support Piłsudski's Legions, when Lviv was occupied by the Imperial Russian Army. She and the Civic Work Committee provided aid to troops and civilians while the city was under Russian authority.[2][17]

In 1918, when Poland regained its independence women were finally given the right to vote.[2] Dulębianka served as a delegate to the Provisional Government Committee and was elected Chair of the Women's League.[1] When the Polish–Ukrainian War broke out in November, she joined the Polish Red Cross, organized the Polish sanitary service, and participated in the defense of Lviv. Initially she worked as a nurse, but gave up the post to serve as a messenger.[1][17] She organized relief efforts for Polish soldiers interned in Ukrainian prisoner-of-war camps.[1][2] Traveling on irregularly-running trains, as well as on foot and horseback, Dulębianka and two hospital workers, Teodozja Dzieduszycka and Maria Opieńska, made their way through the snow to the camp at Mikulińce.[17] In the camp, she contracted typhus and the group returned to Lviv.[1][2][3]

Death and legacy

.jpg.webp)

Dulębianka died on 7 March 1919 in Lviv and was buried in Konopnicka's tomb in Lychakiv Cemetery.[1][10] The funeral was widely attended as a patriotic event, attracting women's movement activists and single mothers, as well as residents of shelters and the residents' guardians.[1][3] Dulębianka's remains were later re-interred in a separate grave.[10]

Dulębianka, like many women's activists, disappeared from history books until the resurgence of feminism in the 1990s.[2] She is recognized for her pioneering work on women's rights, for helping to gain admission of women to the Academy of Fine Arts, and for establishing the first girl's high school in Lviv.[17][22] Her historic campaign in 1908 is remembered as a milestone in the struggle for women's suffrage in Poland.[20][22] In 2018, a film, Siłaczki by Marta Dzido and Piotr Śliwowski was released. It described the struggle of Polish women to gain equal rights and Dulębianka was portrayed by Maria Seweryn.[23]

Notes

- ↑ Tomasik wrote: "Wciąż na zbadanie i opracowanie czeka zarówno homoseksualizm pisarki, jak i kwestia jej zaangażowania feministycznego". [The homosexuality of the writer [Konopnicka] and the question of her feminist involvement are still waiting for investigation and development.][8]

- ↑ Scholars on women's and LGBT history in Poland agree that inadequate investigation has been done into women's relationships at the turn of the 19th century.[11][10][12] Very little is known of lesbian relationships,[12] in part because of stigma associated with homosexuality and in part because accusations of same-sex attraction could be weaponized to discredit ideological or political rivals.[13] Piotr Oczko wrote that scholars of Polish history "tend to be conservative, patriarchal, and deeply traditionalist in their views and consequently show a much greater tendency toward homophobia".[14] Iwona Dadej concurs there has been little written on the topic in Poland and researchers avoid scholarship on women's friendships as not "worthy" enough to document.[11] Relationships which today would be called "lesbian" rarely are labeled as such historically. Instead they are depicted as deep friendships with emotional bonds, which make it difficult to determine whether the couple who were joined in a Boston marriage had romantic attachments or simply lived together for mutually economic benefit.[11][15] Dadej typifies those with a couple's relationship as those in which the women were life companions, sharing both professional and personal experiences. They organized themselves in a family structure, typically were single with no male guardian, and provided for their own economic support.[11]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Kruszyńska 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Górny 2010, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Smoleński 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Konarzewska 2011.

- 1 2 Bobrowska 2012, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 Art Info 2000.

- 1 2 Kłos 2010, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 Tomasik 2015.

- ↑ Wencel 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Gądek 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Dadej 2010, p. 40.

- 1 2 Oczko & Mazur 2013, p. 119.

- ↑ Oczko & Mazur 2013, p. 120.

- ↑ Oczko & Mazur 2013, p. 133.

- ↑ Struzik 2010, p. 55.

- 1 2 Data 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Lisiewicz 2014.

- ↑ "Камінг-аут Марії Дулемб'янки: чи він поставив хрест на її творчості? - krakowchanka.eu". 28 October 2022.

- ↑ Maria Konopnicka Museum 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Semczyszyn 2013, p. 55.

- 1 2 Semczyszyn 2013, p. 56.

- 1 2 Zakrzewski 2015.

- ↑ Horowski 2018.

Further reading

- Tomasik, Krzysztof (2008). Homobiografie: pisarki i pisarze polscy XIX i XX wieku [Homobiographies: male and female Polish writers of the 19th and 20th centuries] (in Polish). Warsaw, Poland: Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej. ISBN 978-83-61006-59-6.

External links

- Bobrowska, Ewa (2012). "Emancypantki? Artystki Polskie w Paryżu na przełomie xix i xx wieku" [Emancipated?: Polish Artists in Paris during the 19th and 20th Century] (PDF). Archiwum Emigracji: Studia, Szkice, Dokumenty (in Polish). Toruń, Poland: Archives of Emigration of the Nicolaus Copernicus University Library. 1–2 (16–17): 11–27. doi:10.12775/AE.2012.001. OCLC 234346206. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Dadej, Iwona (2010). "Przyjaźnie i związki kobiece w ruchu kobiecym przełomu xix i xx wieku [Friendships and women's relationships in the women's movement of the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries]". Krakowski szlak kobiet: przewodniczka po Krakowie emancypantek [Krakow Women's Trail: A Guide to Krakow's Emancipated Women] (in Polish). Vol. 2 (Wyd. 1 ed.). Kraków, Poland: Fundacja Przestrzeń Kobiet. pp. 39–50. ISBN 978-83-928639-1-5.

- Data, Jan (2010). "Maria Konopnicka". literat.ug.edu.pl. Gdańsk, Poland: Virtual Library of Polish Literature. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Gądek, Jacek (20 November 2012). "Maria Konopnicka – lesbijka i zła matka" [Maria Konopnicka – a lesbian and a bad mother]. Onet.pl (in Polish). Kraków, Poland: Ringier Axel Springer Media AG. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- Górny, Maciej (2010). "Maria Dulębianka: The Political Stance of Woman". In Ersoy, Ahmet; Górny, Maciej; Kechriotis, Vangelis (eds.). Modernism: The Creation of Nation-States: Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe 1770–1945. Vol. 3-1: Modernism—The Creation of Nation-States. Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press. pp. 131–139. ISBN 978-963-7326-61-5.

- Horowski, Adam (7 December 2018). "Kobiet prawa - wspólna sprawa" [Women's rights – a common matter]. kultura.poznan.pl (in Polish). Poznań, Poland: City Publishing House. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- Kłos, Anita (2010). "On Maria Konopnicka's Translation of Ada Negri's "Fatalità" and "Tempeste"". Przekładaniec. Kraków, Poland: Jagiellonian University. 24: 111–129. doi:10.4467/16891864ePC.12.006.0568. ISBN 9788323386698. ISSN 1689-1864. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- Konarzewska, Marta (11 May 2011). "Trzy namiętności Marii Dulębianki" [Three passions of Maria Dulębianka]. mpa-kultury (in Polish). Warsaw, Poland: National Center for Culture. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Kruszyńska, Anna (7 March 2019). "100 lat temu zmarła Maria Dulębianka" [100 years ago, Maria Dulębianka died]. Newsletter of the Museum of Polish History (in Polish). Warsaw, Poland. Polish Press Agency. Archived from the original on 7 March 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Lisiewicz, Teodozja (March 2014). "Dulębianka, bojowniczka o prawa kobiet" [Dulębianka, a fighter for women's rights]. Strony: Magazyn Rozmaitosci (in Polish). No. 51. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: White Eagle Association of Poles. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Oczko, Piotr; Mazur, Krystyna (translator) (2013). "Why I Do Not Want to Write about Old-Polish Male-bedders: A Contribution to the "Archeology" of Gay Studies in Poland" (PDF). Teksty Drugie. Warsaw, Poland: Polish Academy of Sciences. 1 (Special: English edition): 118–134. ISSN 0867-0633. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - Semczyszyn, Magdalena (Szczecin) (2013). "Wybory w kurii miejskiej we Lwowie1861–1914 jako pretekst dla ukazaniaspołeczno-politycznego potencjałumiasta" [Elections in the Municipality of Lviv between 1861–1914 as a Pretext to Demonstrate the Socio-Political Outlook for the City] (PDF). Historia Slavorum Occidentis (in Polish). Toruń, Poland: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek. 1 (4): 43–71. ISSN 2084-1213. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- Smoleński, Paweł (10 November 2018). "Kochała Marię Konopnicką, wywalczyła prawa wyborcze kobiet. Dlaczego Dulębianka nie ma pomnika?" [She loved Maria Konopnicka, won women's electoral rights. Why doesn't Dulębianka have a monument?]. Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Warsaw, Poland. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Struzik, Justyna (2010). "O miłości między Innymi [About Love between Others]". Krakowski szlak kobiet: przewodniczka po Krakowie emancypantek [Krakow Women's Trail: A Guide to Krakow's Emancipated Women] (in Polish). Vol. 2 (Wyd. 1 ed.). Kraków, Poland: Fundacja Przestrzeń Kobiet. pp. 51–59. ISBN 978-83-928639-1-5.

- Tomasik, Krzysztof (25 March 2015). "Wielcy i niezapomniani: Maria Konopnicka" [Great and unforgettable: Maria Konopnicka]. queer.pl (in Polish). Kraków, Poland. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- Wencel, Wojciech (12 October 2008). "Wencel gordyjski – Homo wiadomo". Wprost (in Polish). Poznań, Poland. Agencja Wydawniczo-Reklamowa. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- Zakrzewski, Patryk (17 September 2015). "Saying No to Children, Kitchen, Church: The Pioneers of Women's Rights in Poland". Culture.pl. Warsaw, Poland: Adam Mickiewicz Institute. Archived from the original on 7 April 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- "Maria Dulębianka (1861–1919)". Artinfo.pl (in Polish). Warsaw, Poland. 2000. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- "Historia Muzeum". muzeumzarnowiec.pl (in Polish). Żarnowiec, Podkarpackie Voivodeship, Poland: Maria Konopnicka Museum. 2013. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.