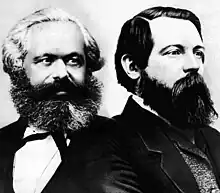

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

Marxist geography is a strand of critical geography that uses the theories and philosophy of Marxism to examine the spatial relations of human geography. In Marxist geography, the relations that geography has traditionally analyzed — natural environment and spatial relations — are reviewed as outcomes of the mode of material production. To fully understand geographical relations, on this view, the social structure must also be examined. Marxist geography attempts to change the basic structure of society.[1]

Definition

Marxism is usually taken to mean the ideas of Marx and Engels, revolutionary socialists such as Lenin and Trotsky and later thinkers building on Marx, such as Gramsci. Marxist geography is the Marxist examination of society 'from the vantage point of space, place, scale and human transformation of nature'. Marxist geographers argue that incorporating Marxist thinking into Geography enriches geographical thinking.[2] For Marxist geographers, it is imperative that space be understood both as a fundamental component of capitalist production and the relations of production.[3][4] Some of the major concepts developed by Marxist geographers include uneven geographical development, historical-geographical materialism,[5] and the production of space.[6] Today, some of the most prominent Marxist Geographers include David Harvey, Andy Merrifield,[7] and Neil Brenner.[8]

Philosophy

Marxist geography is radical in nature and its primary criticism of the positivist spatial science centered on the latter's methodologies, which failed to consider the characteristics of capitalism and abuse that underlie socio-spatial arrangements.[9] As such, early Marxist geographers were explicitly political in advocating for social change and activism; they sought, through application of geographical analysis of social problems, to alleviate poverty and exploitation in capitalist societies.[10] Marxist geography makes exegetical claims regarding how the deep-seated structures of capitalism act as a determinant and a constraint to human agency. Most of these ideas were developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s out of dissatisfaction with the quantitative revolution in geography and spurred on by the founding of the journal Antipode. In some cases, these movements were led by former "space cadets" such as David Harvey and Bill Bunge, who were at the forefront of the quantitative revolution.[11][12]

In order to accomplish such philosophical aims, these geographers rely heavily upon Marxist social and economic theory, drawing on Marxian economics and the methods of historical materialism to tease out the manner in which the means of production control human spatial distribution in capitalist structures. Marx is also invoked to examine how spatial relationships are affected by class. The emphasis is on structure and structural mechanisms.

See also

References

- ↑ Peet, J. Richard (1985). "An Introduction to Marxist Geography". Journal of Geography. 84 (1): 5–10. Bibcode:1985JGeog..84....5P. doi:10.1080/00221348508979261.

- ↑ Das, Raju J (March 2022). "What is Marxist geography today, or what is left of Marxist geography?". Human Geography. 15 (1): 33–44. doi:10.1177/19427786211049757. ISSN 1942-7786.

- ↑ Smith, Neil (2008). Uneven development : nature, capital, and the production of space (Third ed.). Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-3590-2. OCLC 593303347.

- ↑ Harvey, David (2009). Social justice and the city (Revised ed.). Athens. ISBN 978-0-8203-3604-6. OCLC 704418427.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Swyngedouw, Erik A. (1999-01-01). "Marxism and historical-geographical materialism: A spectre is haunting geography". Scottish Geographical Journal. 115 (2): 91–102. Bibcode:1999ScGJ..115...91S. doi:10.1080/14702549908553819. ISSN 1470-2541.

- ↑ Lefebvre, Henri (1991). The production of space. Donald Nicholson-Smith, David Harvey. Oxford, UK. ISBN 0-631-14048-4. OCLC 22624721.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Merrifield, Andy (2014). The new urban question. London. ISBN 978-1-78371-135-2. OCLC 875269584.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Brenner, Neil (2019). New urban spaces : urban theory and the scale question. New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-19-062722-5. OCLC 1056201757.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Cresswell, Tim (2013). Geographic thought : a critical introduction. Chichester, West Sussex, UK. ISBN 978-1-4051-6940-0. OCLC 802319135.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Harvey, David. 1973. "Social Justice and the City"

- ↑ Barnes, Trevor J. (2009-07-06). ""Not Only … But Also": Quantitative and Critical Geography". The Professional Geographer. 61 (3): 292–300. Bibcode:2009ProfG..61..292B. doi:10.1080/00330120902931937. ISSN 0033-0124. S2CID 144095328.

- ↑ Barnes, Trevor J (November 2018). "A marginal man and his central contributions: The creative spaces of William ('Wild Bill') Bunge and American geography". Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. 50 (8): 1697–1715. doi:10.1177/0308518X17707524. ISSN 0308-518X. S2CID 149173226.