Medicare Part D, also called the Medicare prescription drug benefit, is an optional United States federal-government program to help Medicare beneficiaries pay for self-administered prescription drugs.[1] Part D was enacted as part of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 and went into effect on January 1, 2006. Under the program, drug benefits are provided by private insurance plans that receive premiums from both enrollees and the government. Part D plans typically pay most of the cost for prescriptions filled by their enrollees.[2] However, plans are later reimbursed for much of this cost through rebates paid by manufacturers and pharmacies.[3]

Part D enrollees cover a portion of their own drug expenses by paying cost-sharing. The amount of cost-sharing an enrollee pays depends on the retail cost of the filled drug, the rules of their plan, and whether they are eligible for additional Federal income-based subsidies. Prior to 2010, enrollees were required to pay 100% of their retail drug costs during the coverage gap phase, commonly referred to as the "doughnut hole.” Subsequent legislation, including the Affordable Care Act, “closed” the doughnut hole from the perspective of beneficiaries, largely through the creation of a manufacturer discount program.[4]

In 2019, about three-quarters of Medicare enrollees obtained drug coverage through Part D.[5] Program expenditures were $102 billion, which accounted for 12% of Medicare spending.[6] Through the Part D program, Medicare finances more than one-third of retail prescription drug spending in the United States.[7]

Program specifics

Eligibility and enrollment

To enroll in Part D, Medicare beneficiaries must also be enrolled in either Part A or Part B. Beneficiaries can participate in Part D through a stand-alone prescription drug plan or through a Medicare Advantage plan that includes prescription drug benefits.[8] Beneficiaries can enroll directly through the plan's sponsor or through an intermediary. Medicare beneficiaries who delay enrollment into Part D may be required to pay a late-enrollment penalty.[9] In 2019, 47 million beneficiaries were enrolled in Part D, which represents three-quarters of Medicare beneficiaries.[5]

Plans offered

Part D benefits are provided through private plans approved by the federal government. The number of offered plans varies geographically, but a typical enrollee will have dozens of options to choose from.[10] Although plans are restricted by numerous program requirements, plans vary in many ways. Among other factors, enrollees often compare premiums, covered drugs, and cost-sharing policies when selecting a plan.

Medicare offers an interactive online tool [11] that allows for comparison of coverage and costs for all plans in a geographic area. The tool lets users input their own list of medications and then calculates personalized projections of the enrollee's annual costs under each plan option. Plans are required to submit biweekly data updates that Medicare uses to keep this tool updated throughout the year.

Costs to beneficiaries

Beneficiary cost sharing

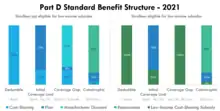

Part D includes a statutorily defined "standard benefit" that is updated on an annual basis. All Part D sponsors must offer a plan that follows the standard benefit. The standard benefit is defined in terms of the benefit structure and without mandating the drugs that must be covered. For example, under the 2020 standard benefit, beneficiaries first pay a 100% coinsurance amount up to a $435 deductible.[12] Second, beneficiaries pay a 25% coinsurance amount up to an Out-of-Pocket Threshold of $6,350. In the final benefit phase, beneficiaries pay the greater of a 5% coinsurance amount or a nominal co-payment amount. These three benefit phases are referred to as the Deductible, Initial Coverage Limit, and the Catastrophic phase.

The "Out-of-Pocket Threshold" is not a cap on out-of-pocket spending, as beneficiaries continue to accrue cost-sharing expenses in the Catastrophic phase. In 2020, beneficiaries would typically reach this threshold as their retail drug spending approached $10,000. When patients enter the Catastrophic phase, the amount they have paid in cost-sharing is typically much less than the Out-of-Pocket Threshold. This is because the standard benefit requires plans to include additional amounts, such as manufacturer discounts, when determining if the Out-of-Pocket Threshold has been met.

Part D sponsors may also offer plans that differ from the standard benefit, provided that these alternative benefit structures do not result in higher average cost-sharing. In practice, most enrollees do not elect for standard benefit plans, instead opting for plans without deductibles and with tiered drug co-payments rather than coinsurance.[8] Enrollees must pay an additional premium amount to be enrolled in a plan with cost-sharing that is lower than the standard benefit, and this additional amount is not Federally-subsidized.

Prior to 2010, the standard benefit included a Coverage Gap phase in which, after accruing significant spending, relatively-high cost enrollees were required to pay a 100% coinsurance amount until they entered the Catastrophic phase. This Coverage Gap phase is commonly referred to as "the Donut Hole." Beginning with the Affordable Care Act, cost-sharing in the Coverage Gap phase has been gradually reduced. Despite no longer triggering elevated cost-sharing, the Coverage Gap phase continues to exist for other administrative purposes.

Beneficiary premiums

In 2020, the average monthly Part D premium across all plans was $27.[13] Premiums for stand-alone PDPs are 3 times higher than premiums for MA-PDs, as Medicare Advantage plans often use federal rebates to reduce premiums for drug coverage.[14] Enrollees typically pay their premiums directly to plans, though they may opt to have their premiums automatically deducted from their Social Security checks.

Plans offer competitive premiums to attract enrollees. Premiums must cover the cost of both plan liability and the reinsurance subsidy. From 2017 to 2020, despite rising per capita drug spending, premiums decreased by 16%.[13][15] Plans have been able to lower premiums by negotiating larger rebates from manufacturers and pharmacies. Between 2017 and 2020, the percentage of drug costs rebated back to plans increased from 22% to 28%.[16] In addition, the standard benefit was changed in 2019 to increase mandatory manufacturer discounts in the Coverage Gap.[17][18]

Part D practices community rating, with all enrollees in a plan being assigned the same premium. Enrollees do pay more in premiums if they enroll in higher-than-average-cost plans or in plans that offer enhanced benefits. Like in Part B, higher-income enrollees are required to pay an additional premium amount. Low-income enrollees may have their premium reduced or eliminated if they qualify for the low-income premium subsidy.

For 2022, costs for stand-alone Part D plans in the 10 major U.S. markets ranged from a low of $6.90-per-month (Dallas and Houston) to as much as $160.20-per-month (San Francisco). A study by the American Association for Medicare Supplement Insurance reported the lowest and highest 2022 Medicare Plan D costs[19] for the top-10 markets.

Retiree drug subsidy (RDS)

Retiree Drug Subsidy (RDS) is a program that provides financial assistance to employers who offer prescription drug coverage to their retirees. The subsidy is a feature of Medicare Part D, designed to help retirees access affordable prescription medications.[20]

Low-income subsidies

Beneficiaries with income below 150% of the poverty line are eligible for the low-income subsidy, which helps pay for premiums and cost-sharing. Depending on income-level and assets, some beneficiaries qualify for the full low-income subsidy, while others are eligible for a partial subsidy. All low-income subsidy enrollees still pay small copayment amounts.

Low-income enrollees tend to have more chronic conditions than other enrollees.[21] Low-income subsidy enrollees represent about one-quarter of enrollment,[22] but about half of the program's retail drug spending.[2] Nearly 30% of Federal spending on Part D goes towards paying for the low-income subsidy.[23]

In addition to receiving premium and cost-sharing subsidies, certain program rules apply differently for low-income subsidy enrollees. Beneficiaries of the low-income subsidy are exempt from the Coverage Gap Manufacturer Discount Program. Low-income subsidy enrollees are also allowed to change plans more frequently than other enrollees.[24]

Excluded drugs

While Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) does not have an established formulary, Part D drug coverage excludes drugs not approved by the Food and Drug Administration, drugs not available by prescription for purchase in the United States, and drugs for which payments would be available under Part B.[25]

Part D coverage excludes drugs or classes of drugs that may be excluded from Medicaid coverage. These may include:

- Drugs used for anorexia, weight loss, or weight gain

- Drugs used to promote fertility

- Drugs used for erectile dysfunction

- Drugs used for cosmetic purposes (hair growth, etc.)

- Drugs used for the symptomatic relief of cough and colds

- Prescription vitamin and mineral products, except prenatal vitamins and fluoride preparations

- Drugs where the manufacturer requires as a condition of sale any associated tests or monitoring services to be purchased exclusively from that manufacturer or its designee

While these drugs are excluded from basic Part D coverage, drug plans can include them as a supplemental benefit, provided they otherwise meet the definition of a Part D drug. However plans that cover excluded drugs are not allowed to pass on those costs to Medicare, and plans are required to repay CMS if they are found to have billed Medicare in these cases.[26]

Plan formularies

Part D plans are not required to pay for all covered Part D drugs.[27] They establish their own formularies, or list of covered drugs for which they will make payment, as long as the formulary and benefit structure are not found by CMS to discourage enrollment by certain Medicare beneficiaries. Part D plans that follow the formulary classes and categories established by the United States Pharmacopoeia will pass the first discrimination test. Plans can change the drugs on their formulary during the course of the year with 60 days' notice to affected parties.

The primary differences between the formularies of different Part D plans relate to the coverage of brand-name drugs. Typically, each Plan's formulary is organized into tiers, and each tier is associated with a set co-pay amount. Most formularies have between 3 and 5 tiers. The lower the tier, the lower the co-pay. For example, Tier 1 might include all of the Plan's preferred generic drugs, and each drug within this tier might have a co-pay of $5 to $10 per prescription. Tier 2 might include the Plan's preferred brand drugs with a co-pay of $40 to $50, while Tier 3 may be reserved for non-preferred brand drugs which are covered by the plan at a higher co-pay, perhaps $70 to $100. Tiers 4 and higher typically contain specialty drugs, which have the highest co-pays because they are generally more expensive. By 2011 in the United States a growing number of Medicare Part D health insurance plans had added the specialty tier.[28]: 1

History

Upon enactment in 1965, Medicare included coverage for physician-administered drugs, but not self-administered prescription drugs. While some earlier drafts of the Medicare legislation included an outpatient drug benefit, those provisions were dropped due to budgetary concerns.[29] In response to criticism regarding this omission, President Lyndon Johnson ordered the formation of the Task Force on Prescription Drugs.[30] The Task Force conducted a comprehensive review of the American prescription drug market and reported that many elderly Americans struggled to afford their medications.[31]

Despite the findings and recommendations of the Task Force, initial efforts to create a Medicare outpatient drug benefit were unsuccessful. In 1988, the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act temporarily expanded program benefits to include self-administered drugs.[32] However, this legislation was repealed just one year later, partially due to concerns regarding premium increases. The 1993 Clinton Health Reform Plan also included an outpatient drug benefit, but that reform effort ultimately failed due to a lack of public support.[33]

In the decades following Medicare's passage, prescription drug spending grew and became increasingly financed through third-party payment. Following an era of modest growth, per capita drug spending began growing rapidly in the 1980s.[34] This growth was partially spurred by the launch of many billion dollar “blockbuster drugs” like Lipitor, Celebrex, and Zoloft.[35] At the time of Medicare's passage, more than 90% of drug spending was paid out-of-pocket.[34] Over the following 35-years, third-party payment for prescription drugs became increasingly common. By the end of the century, less than one-third of drug spending was paid out-of-pocket. Despite the absence of a Medicare drug benefit, about 70% of Medicare enrollees obtained drug coverage through other means, often through an employer or Medicaid.[36]

Medicare began offering subsidized outpatient drug coverage in the mid-2000s. In the 2000 presidential election, both the Democratic and Republican candidates campaigned on the promise of using the projected federal budget surplus to fund a new Medicare drug entitlement program.[37] Following his electoral victory, President George W. Bush promoted a general vision of using private health plans to provide drug coverage to Medicare beneficiaries.[30] Rather than demand that the plan be budget neutral, President Bush supported up to $400 billion in new spending for the program. In 2003, President Bush signed the Medicare Modernization Act, which authorized the creation of the Medicare Part D program. The program was implemented in 2006.

To keep the plan's cost projections below the $400 billion constraint set by leadership, policymakers devised the infamous “donut hole.” After exceeding a modest deductible, beneficiaries would pay 25% cost-sharing for covered drugs.[30] However, once their spending reached an “initial coverage limit,” originally set at $2,250, their cost-sharing would return to 100% of the drug's cost. This loss in coverage would continue until the patient surpassed an out-of-pocket threshold Beneficiaries were often confused by this complicated design,[38] and research consistently found that this coverage gap reduced medication adherence.[39][40][41] The Affordable Care Act and subsequent legislation phased-out the coverage gap from the perspective of beneficiaries. As of 2020, beneficiary cost-sharing on covered drugs never exceeds 25% of the drug's cost after an enrollee meets their deductible.[42]

Program costs

In 2019, total drug spending for Medicare Part D beneficiaries was about 180 billion dollars.[43] One-third of this amount, about 120 billion dollars, was paid by prescription drug plans. This plan liability amount was partially offset by about 50 billion dollars in discounts, mostly in the form of manufacturer and pharmacy rebates.[16] This implied a net plan liability (i.e. net of discounts) of roughly 70 billion dollars. To finance this cost, plans received roughly 50 billion in federal reinsurance subsidies, 10 billion in federal direct subsidies, and 10 billion in enrollee premiums.[23]

In addition to the 60 billion dollars paid in federal insurance subsidies, the federal government also paid about 30 billion dollars in cost-sharing subsidies for low-income enrollees.[23] The federal government also collected roughly 20 billion in offsetting receipts. These offsets included both state payments made on behalf of Medicare beneficiaries who also qualify for full Medicaid benefits and additional premiums paid by high-income enrollees. After accounting for these offsets, the net federal cost of Part D was about 70 billion dollars.[44]

Implementation issues

- Plan and Health Care Provider goal alignment: PDP's and MA's are rewarded for focusing on low-cost drugs to all beneficiaries, while providers are rewarded for quality of care – sometimes involving expensive technologies.

- Conflicting goals: Plans are required to have a tiered exemptions process for beneficiaries to get a higher-tier drug at a lower cost, but plans must grant medically necessary exceptions. However, the rule denies beneficiaries the right to request a tiering exception for certain high-cost drugs.

- Lack of standardization: Because each plan can design their formulary and tier levels, drugs appearing on Tier 2 in one plan may be on Tier 3 in another plan. Co-pays may vary across plans. Some plans have no deductibles and the coinsurance for the most expensive drugs varies widely. Some plans may insist on step therapy, which means that the patient must use generics first before the company will pay for higher-priced drugs. Patients can appeal and insurers are required to respond within a short timeframe, so as to not further the burden on the patient.

- Standards for electronic prescribing for Medicare Part D conflict with regulations in many U.S. states.[45]

Impact on beneficiaries

A 2008 study found that the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries who reported forgoing medications due to cost dropped with Part D, from 15.2% in 2004 and 14.1% in 2005 to 11.5% in 2006. The percentage who reported skipping other basic necessities to pay for drugs also dropped, from 10.6% in 2004 and 11.1% in 2005 to 7.6% in 2006. The very sickest beneficiaries reported no reduction, but fewer reported forgoing other necessities to pay for medicine.[46][47]

A parallel study found that Part D beneficiaries skip doses or switch to cheaper drugs and that many do not understand the program.[46] Another study found that Part D resulted in modest increases in average drug utilization and decreases in average out-of-pocket expenditures.[48] Further studies by the same group of researchers found that the net impact among beneficiaries was a decrease in the use of generic drugs.[49]

A further study concludes that although a substantial reduction in out-of-pocket costs and a moderate increase in utilization among Medicare beneficiaries during the first year after Part D, there was no evidence of improvement in emergency department use, hospitalizations, or preference-based health utility for those eligible for Part D during its first year of implementation.[50] It was also found that there were no significant changes in trends in the dual eligibles' out-of-pocket expenditures, total monthly expenditures, pill-days, or total number of prescriptions due to Part D.[51]

A 2020 study found that Medicare Part D led to a sharp reduction in the number of people over the age of 65 who worked full-time. The authors say that this is evidence that before the change, people avoided retiring in order to maintain employer-based health insurance.[52][53]

Criticisms

The federal government is not permitted to negotiate Part D drug prices with drug companies, as federal agencies do in other programs. Numerous critics view this as a mismanagement of taxpayer funds, whereas proponents contend that allowing price negotiation might inhibit innovation by reducing profits for pharmaceutical companies.[54] The Department of Veterans Affairs, which is allowed to negotiate drug prices and establish a formulary, has been estimated to pay between 40%[55] and 58%[56] less for drugs, on average, than Part D. On the other hand, the VA only covers about half the brands that a typical Part D plan covers.

Part of the issue is that Medicare does not pay for Part D drugs, and so has no actual leverage. Part D drug providers are using the private insurer leverage, which is generally a larger block of consumers than the 40 million or so actually using Medicare parts A and B for medical care.

Although generic versions of [frequently prescribed to the elderly] drugs are now available, plans offered by three of the five [exemplar Medicare Part D] insurers currently exclude some or all of these drugs from their formularies. ... Further, prices for the generic versions are not substantially lower than their brand-name equivalents. The lowest price for simvastatin (generic Zocor) 20 mg is 706 percent more expensive than the VA price for brand-name Zocor. The lowest price for sertraline HCl (generic Zoloft) is 47 percent more expensive than the VA price for brand-name Zoloft."

— Families USA 2007 "No Bargain: Medicare Drug Plans Deliver High Prices"

Estimating how much money could be saved if Medicare had been allowed to negotiate drug prices, economist Dean Baker gives a "most conservative high-cost scenario" of $332 billion between 2006 and 2013 (approximately $50 billion a year). Economist Joseph Stiglitz in his book entitled The Price of Inequality estimated a "middle-cost scenario" of $563 billion in savings "for the same budget window".[57]: 48

Former Congressman Billy Tauzin, R–La., who steered the bill through the House, retired soon after and took a $2 million a year job as president of Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), the main industry lobbying group. Medicare boss Thomas Scully, who threatened to fire Medicare Chief Actuary Richard Foster if he reported how much the bill would actually cost, was negotiating for a new job as a pharmaceutical lobbyist as the bill was working through Congress.[58][59] 14 congressional aides quit their jobs to work for related lobbies immediately after the bill's passage.[60]

In response, free-market think tank Manhattan Institute issued a report by professor Frank Lichtenberg that said the VA National Formulary excludes many new drugs. Only 38% of drugs approved in the 1990s and 19% of the drugs approved since 2000 were on the formulary.

In 2012, the plan required Medicare beneficiaries whose total drug costs reach $2,930 to pay 100% of prescription costs until $4,700 is spent out of pocket. (The actual threshold amounts change year-to-year and plan-by-plan, and many plans offered limited coverage during this phase.) While this coverage gap does not affect the majority of program participants, about 25% of beneficiaries enrolled in standard plans find themselves in this gap.[61]

As a candidate, Barack Obama proposed "closing the 'doughnut hole'" and subsequently proposed a plan to reduce costs for recipients from 100% to 50% of these expenses.[62] The cost of the plan would be borne by drug manufacturers for name-brand drugs and by the government for generics.[62]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kirchhoff, Suzanne M. (August 13, 2018). Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit (PDF). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- 1 2 A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program (PDF). Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. 2020. p. 168.

- ↑ Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy (PDF). Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. 2020. p. 430.

- ↑ Closing the Coverage Gap — Medicare Prescription Drugs Are Becoming More Affordable (PDF). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2014.

- 1 2 "Medicare—CBO's Baseline as of March 6, 2020" (PDF). CBO.gov. March 6, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ↑ Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy (PDF). Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. 2021. p. 411.

- ↑ "Retail Sales for Prescription Drugs Filled at Pharmacies by Payer". Kaiser Family Foundation. 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- 1 2 "Medicare: A Primer," Archived 2010-06-12 at the Wayback Machine Kaiser Family Foundation, April 2010.

- ↑ "Part D late enrollment penalty". Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- ↑ "An Overview of the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit". KFF. 2020-10-14. Retrieved 2021-07-09.

- ↑ "Medicare Plan Finder for Health, Prescription Drug and Medigap plans". www.medicare.gov. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- ↑ "An Overview of the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit". 14 October 2020.

- 1 2 A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program(PDF) Archived 2021-07-11 at the Wayback Machine. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. 2020. p. 155.

- ↑ Damico, Anthony (2020-10-29). "Medicare Part D: A First Look at Medicare Prescription Drug Plans in 2021". KFF. Retrieved 2021-07-12.

- ↑ "Medicare Part D Utilization: Average Annual Gross Drug Costs Per Part D Enrollee, by Type of Plan, Low Income Subsidy (LIS) Eligibility, and Brand/Generic Drug Classification" (PDF) Archived 2021-07-11 at the Wayback Machine. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- 1 2 2020 Medicare Trustees Report (PDF) Archived 2021-06-23 at the Wayback Machine. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2020. p. 142.

- ↑ "2022 Medicare Drug Plan Prices - Best Part D Plan Prices Information". MedicareSupp.org. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- ↑ Damico, Anthony (2021-06-08). "Key Facts About Medicare Part D Enrollment, Premiums, and Cost Sharing in 2021". KFF. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ↑ "American Association for Medicare Supplement Insurance". American Association for Medicare Supplement Insurance. October 2022.

- ↑ "Retiree Drug Subsidy (RDS)". www.rds.cms.hhs.gov. Retrieved 2023-10-05.

- ↑ Shoemaker, J. Samantha; Davidoff, Amy J.; Stuart, Bruce; Zuckerman, Ilene H.; Onukwugha, Eberechukwu; Powers, Christopher (2012). "Eligibility and Take-up of the Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidy". Inquiry: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 49 (3): 214–230. doi:10.5034/inquiryjrnl_49.03.04. PMID 23230703. S2CID 36621020.

- ↑ 2020 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE BOARDS OF TRUSTEES OF THE FEDERAL HOSPITAL INSURANCE AND FEDERAL SUPPLEMENTARY MEDICAL INSURANCE TRUST FUNDS (PDF). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2020. p. 140.

- 1 2 3 2020 Medicare Trustees Report (PDF) Archived 2021-06-23 at the Wayback Machine. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2020. p. 145.

- ↑ Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit (PDF). Congressional Research Service. 2020. p. 4.

- ↑ "Relationship between Part B and Part D Coverage" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2007.

- ↑ "Report on the Medicare Drug Discount Card Program Sponsor McKesson Health Solutions, A-06-06-00022" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- ↑ "Part D / Prescription Drug Benefits". Center for Medicare Advocacy. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ↑ Elias, Eve Carolyn (May 2011). Analysis of out-of-pocket expenditures of oral oncologics for Tennessee recipients of Medicare Part D (PDF). The University of Tennessee (Thesis). Master of Science. p. 54. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ↑ Marmor TR. The Politics of Medicare. 2nd ed. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2000.

- 1 2 3 Oliver, Thomas R; Lee, Philip R; Lipton, Helene L (June 2004). "A Political History of Medicare and Prescription Drug Coverage". The Milbank Quarterly. 82 (2): 283–354. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00311.x. ISSN 0887-378X. PMC 2690175. PMID 15225331.

- ↑ Smith, M. C. (2001). Prescription drugs under Medicare: the legacy of the Task Force on Prescription Drugs. CRC Press.

- ↑ Rice, Thomas; Desmond, Katherine; Gabel, Jon (1990-01-01). "The Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act: A Post-Mortem". Health Affairs. 9 (3): 75–87. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.9.3.75. ISSN 0278-2715. PMID 2227787.

- ↑ Skocpol, Theda (1995-01-01). "The Rise and Resounding Demise of the Clinton Plan". Health Affairs. 14 (1): 66–85. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.14.1.66. ISSN 0278-2715. PMID 7657229.

- 1 2 "National Health Expenditure Data | CMS". www.cms.gov. Retrieved 2021-07-19.

- ↑ Aitken, Murray; Berndt, Ernst R.; Cutler, David M. (January 2009). "Prescription drug spending trends in the United States: looking beyond the turning point". Health Affairs. 28 (1): w151–160. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.w151. ISSN 1544-5208. PMID 19088102.

- ↑ Kreling, D. H., Mott, D. A., & Wiederholt, J. B. (1997). Why are prescription drug costs rising. Hospital, 1994(1995), 1996.

- ↑ Blumenthal, D., & Morone, J. (2010). The heart of power: health and politics in the Oval Office. Univ of California Press.

- ↑ Polinski, Jennifer M.; Bhandari, Aman; Saya, Uzaib Y.; Schneeweiss, Sebastian; Shrank, William H. (2010-05-01). "Medicare beneficiaries' knowledge of and choices regarding Part D, 2005 – present". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 58 (5): 950–966. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02812.x. ISSN 0002-8614. PMC 2909383. PMID 20406313.

- ↑ Gu, Q., Zeng, F., Patel, B. V., & Tripoli, L. C. (2010). Part D coverage gap and adherence to diabetes medications. The American journal of managed care, 16(12), 911-918.

- ↑ Li, Pengxiang; McElligott, Sean; Bergquist, Henry; Schwartz, J. Sanford; Doshi, Jalpa A. (2012-06-05). "Effect of the Medicare Part D Coverage Gap on Medication Use Among Patients With Hypertension and Hyperlipidemia". Annals of Internal Medicine. 156 (11): 776–784. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00004. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 22665815. S2CID 43798967.

- ↑ Zhang, Yuting; Baik, Seo Hyon; Lave, Judith R. (2013-06-01). "Effects of Medicare Part D Coverage Gap on Medication Adherence". The American Journal of Managed Care. 19 (6): e214–e224. ISSN 1088-0224. PMC 3711553. PMID 23844750.

- ↑ Damico, Anthony (2018-08-21). "Closing the Medicare Part D Coverage Gap: Trends, Recent Changes, and What's Ahead". KFF. Retrieved 2021-07-19.

- ↑ A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program Archived 2021-08-10 at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. 2021. p. 171.

- ↑ 2020 Medicare Trustees Report (PDF) Archived 2021-09-13 at the Wayback Machine. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2020. p. 98.

- ↑ The Institute of Medicine (2006). "Preventing Medication Errors". The National Academies Press. Retrieved 2006-07-21.

- 1 2 Gardner, Amanda (2008-04-22). "Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Shows Mixed Results". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-01-06.

- ↑ Madden, Jeanne M.; Graves, Amy J.; Zhang, Fang; Adams, Alyce S.; Briesacher, Becky A.; Ross-Degnan, Dennis; Gurwitz, Jerry H.; Pierre-Jacques, Marsha; Safran, Dana Gelb; Adler, Gerald S.; Soumerai, Stephen B. (2008-04-23). "Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence and Spending on Basic Needs Following Implementation of Medicare Part D". JAMA. 299 (16): 1922–1928. doi:10.1001/jama.299.16.1922. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 3781951. PMID 18430911.

- ↑ Zhang, JX; Yin, W; Sun, SX; Alexander, GC (2008). "The impact of the Medicare Part D prescription benefit on generic drug use". J Gen Intern Med. 23 (10): 1673–8. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0742-6. PMC 2533371. PMID 18661190.

- ↑ Zhang, J; Yin, W; Sun, S; Alexander, GC (2008). "Impact of the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit on the use of generic drugs". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 23 (10): 1673–1678. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0742-6. PMC 2533371. PMID 18661190.

- ↑ Liu, Frank Xiaoqing; Alexander, G. Caleb; Crawford, Stephanie Y.; Pickard, A. Simon; Hedeker, Donald; Walton, Surrey M. (August 2011). "The impact of Medicare Part D on out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs, medication utilization, health resource utilization, and preference-based health utility". Health Services Research. 46 (4): 1104–1123. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01273.x. PMC 3165180. PMID 21609328.

- ↑ Basu, A; Yin W; Alexander GC (February 2010). "Impact of Medicare Part D on Medicare-Medicaid dual-eligible beneficiaries' prescription utilization and expenditures". Health Services Research. 1. 45 (1): 133–151. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01065.x. PMC 2813441. PMID 20002765.

- ↑ Wettstein, Gal (2020). "Retirement Lock and Prescription Drug Insurance: Evidence from Medicare Part D". American Economic Journal: Economic Policy. 12 (1): 389–417. doi:10.1257/pol.20160560. ISSN 1945-7731. S2CID 84836195.

- ↑ "Will work for insurance". www.aeaweb.org. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ↑ Gailey, Adam; Lakdawalla, Darius; Sood, Neeraj (January 2010), Dor, Avi (ed.), "Patents, innovation, and the welfare effects of Medicare Part D", Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 22: 317–344, doi:10.1108/s0731-2199(2010)0000022017, ISBN 978-1-84950-716-5, PMC 3988702, PMID 20575239

- ↑ Austin, Frakt; Steven D. Pizer; Roger Feldman (May 2012). "Should Medicare Adopt the Veterans Health Administration Formulary?". Health Economics. 21 (5): 485–95. doi:10.1002/hec.1733. PMID 21506191. S2CID 41721060.

- ↑ "No Bargain: Medicare Drug Plans Deliver High Prices" (PDF). Families USA. 2007. Retrieved 2012-05-10.

- ↑ Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2012). The Price of Inequality. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 560. ISBN 978-0393345063.

- ↑ Under The Influence: 60 Minutes' Steve Kroft Reports On Drug Lobbyists' Role in Passing Bill That Keeps Drug Prices High Archived 2013-10-08 at the Wayback Machine. Lists Senators and Congress members who went on to high-paying jobs as pharmaceutical industry lobbyists after voting for Medicare Part D.

- ↑ The K Street Prescription Archived 2014-01-12 at the Wayback Machine, By Paul Krugman, New York Times, January 20, 2006.

- ↑ Singer, Michelle (March 29, 2007). "Under The Influence: 60 Minutes' Steve Kroft Reports On Drug Lobbyists' Role in Passing Bill That Keeps Drug Prices High". CBS News 60 Minutes.

- ↑ Zhang Y, Donohue JM, Newhouse JP, Lave JR. The effects of the coverage gap on drug spending: a closer look at Medicare Part D Archived 2015-10-15 at the Wayback Machine. Health Affairs. 2009 Mar-Apr;28(2):w317-25.

- 1 2 "Obama Unveils 'Doughnut Hole' Solution: People who fall in the Part D coverage gap would only pay half the cost of brand-name medications". AARP Bulletin Today. 2009-06-22.

References

- Cost and Utilization of Outpatient Prescription Drugs Among the Elderly: Implications for a Medicare Benefit, 2003, Nashville, Tenn

- Managed Care Programs

- The American Journal of Managed Care

- Zhang J, Yin W, Sun S, Alexander GC. Impact of Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit on the use of generic drugs Journal of Internal Medicine. 2008;23:1673-1678.

- Yin W, Basu A, Zhang J, Rabbani A, Meltzer DO, Alexander GC. Impact of the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Benefit on drug utilization and out-of-pocket expenditures Archived 2012-09-11 at the Wayback Machine Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148:169-177.

- Epstein, AJ; Rathore, SR; Alexander, GC; Katcham, J (2008). "Physicians' Views on Access to Prescription Drugs under Medicare Part D". American Journal of Managed Care. 14: SP5–SP13.

- Federman, AD; Alexander, GC; Shrank, WH (2006). "Simplifying the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit for physicians and patients". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 81 (9): 1217–1221. doi:10.4065/81.9.1217. PMID 16970218.

- "Understanding Medicare Enrollment Periods" (PDF). Tip Sheets. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. February 2011. CMS Product No. 11219. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-04.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Further reading

2019

- McManus, John (July 2019). "Restructuring of Medicare Part D Imminent". Life Science Leader. 11 (7): 10–11.

2007

- "The Big Drug Scam", by Rich Lowry, National Review Online, January 16, 2007.

2006

- "A Recipe for Cynicism", by Jonah Goldberg, National Review Online, November 29, 2006.

- "Success of Drug Plan Challenges Democrats", by Lori Montgomery and Christopher Lee, Washington Post, November 26, 2006.

- "Medicare Part D Gets a Bipartisan F", by Jerry Mazza, Online Journal, February 3, 2006.

- "Part D From Outer Space" Archived 2008-12-03 at the Wayback Machine, by Trudy Lieberman, The Nation, January 30, 2006.

- The States Step In As Medicare Falters; Seniors Being Turned Away, Overcharged Under New Prescription Drug Program, by Ceci Connolly, Washington Post, Saturday, January 14, 2006.

- Troubles with Medicare Prescription Drug Program Archived 2012-11-09 at the Wayback Machine, PBS NewsHour with Jim Lehrer, January 16, 2006.

2004

- "The Great Society Meets the 21st Century", by Michael Johns, Orthopedic Technology Review, January 2004.

External links

- Government resources

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

- Medicare.gov, the official website for people with Medicare.

- Prescription Drug Coverage homepage at Medicare.gov, a central location for Medicare's web-based information about the Part D benefit.

- "Landscape of Plans", at Medicare.gov, state-by-state breakdown of all Part D plans available by area, including stand-alone (drug coverage only) plans and other coverage plans.

- State Pharmaceutical Assistance Programs at Medicare.gov, links to contact information for each state's SPAP program.

- Enroll in a Medicare Prescription Drug Plan at Medicare.gov, the web-based tool for enrolling online in a Part D plan.

- Official Medicare publications at Medicare.gov, includes official publications about the Part D benefit.

- Medicare & You handbook for 2006 at Medicare.gov, includes information about the Part D benefit.

- Information about the 1-800-MEDICARE helpline from Medicare.gov, a 24X7 toll-free number where anyone can call with questions about the Part D benefit.

- Prescription Drug Coverage homepage at Medicare.gov, a central location for Medicare's web-based information about the Part D benefit.

- Other resources

- "Medicare Part D Briefing Room", from the American Society of Consultant Pharmacists.

- "Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Weekly Q&A Column", from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

- "My Medicare Matters", sponsored by the National Council on Aging.

- "Medicare Part D Health Issues", from the National Senior Citizens Law Center.

- "Bob Dole On Medicare" - Enrollment/education campaign by former Senator Bob Dole and Pfizer.

- Spending Patterns for Prescription Drugs under Medicare Part D Congressional Budget Office

- "Press Gaggle" with Scott McClellan and Dr. Mark McClellan that includes discussion on Medicare prescription drug benefit, August 29, 2005.