| Metallothionein superfamily (plant) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||

| Symbol | Metallothionein_sfam | ||||||||||

| Pfam | PF00131 | ||||||||||

| InterPro | IPR003019 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

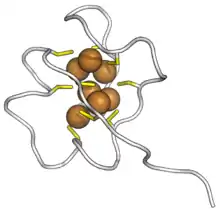

| Yeast MT | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Saccharomyces cerevisiae MT metallothionein bound to copper ions. Cysteines in yellow, copper in brown. (PDB: 1AQS) | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Yeast metallothionein | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF11403 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0461 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR022710 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

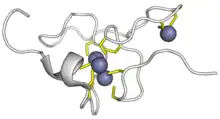

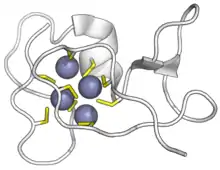

| Cyanobacterial SmtA | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cyanobacterial SmtA metallothionein bound to zinc ions. Cysteines in yellow, zinc in purple. (PDB: 1JJD) | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Bacterial metallothionein | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF02069 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0461 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000518 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Metallothionein (MT) is a family of cysteine-rich, low molecular weight (MW ranging from 500 to 14000 Da) proteins. They are localized to the membrane of the Golgi apparatus. MTs have the capacity to bind both physiological (such as zinc, copper, selenium) and xenobiotic (such as cadmium, mercury, silver, arsenic, lead) heavy metals through the thiol group of its cysteine residues, which represent nearly 30% of its constituent amino acid residues.[2]

MT was discovered in 1957 by Vallee and Margoshe from purification of a Cd-binding protein from horse (equine) renal cortex.[3] MT plays a role in the protection against metal toxicity and oxidative stress, and is involved in zinc and copper regulation.[4] There are four main isoforms expressed in humans (family 1, see chart below): MT1 (subtypes A, B, E, F, G, H, L, M, X), MT2, MT3, and MT4. In the human body, large quantities are synthesised primarily in the liver and kidneys. Their production is dependent on availability of the dietary minerals such as zinc, copper, and selenium, as well as the amino acids histidine and cysteine.

Metallothioneins are rich in thiols, causing them to bind a number of trace metals. Metallothionein is one of the few eukaryotic proteins playing a substantial role in metal detoxification. Zinc and Cadmium are tetrahedrally coordinated to cysteine residues, and each metallothionein protein molecule may bind up to 7 atoms of Zn or Cd.[5] The biosynthesis of metallothionein appears to increase several-fold during periods of oxidative stress to shield the cells against cytotoxicity and DNA damage. Metallothionein biosynthesis can also be induced by certain hormones, pharmaceuticals, alcohols, and other compounds.[6] Metallothionein expression is upregulated during fetal development, particularly in liver tissue.[7]

Structure and classification

MTs are present in a vast range of taxonomic groups, ranging from prokaryotes (such as the cyanobacteria Synechococcus sp.), protozoa (such as the ciliate Tetrahymena genera), plants (such as Pisum sativum, Triticum durum, Zea mays, or Quercus suber), yeast (such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida albicans, or Neurospora crassa), invertebrates (such as the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, the insect Drosophila melanogaster, the mollusc Mytilus edulis, or the echinoderm Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) and vertebrates (such as the chicken Gallus gallus, or the mammalian Homo sapiens or Mus musculus).

The MTs from this diverse taxonomic range represent a high-heterogeneity sequence (regarding molecular weight and number and distribution of Cys residues) and do not show general homology; in spite of this, homology is found inside some taxonomic groups (such as vertebrate MTs).

From their primary structure, MTs have been classified by different methods. The first one dates from 1987, when Fowler et al., established three classes of MTs: Class I, including the MTs which show homology with horse MT, Class II, including the rest of the MTs with no homology with horse MT, and Class III, which includes phytochelatins, Cys-rich enzymatically synthesised peptides. The second classification was performed by Binz and Kagi in 2001, and takes into account taxonomic parameters and the patterns of distribution of Cys residues along the MT sequence. It results in a classification of 15 families for proteinaceous MTs. Family 15 contains the plant MTs, which in 2002 have been further classified by Cobbet and Goldsbrough into 4 Types (1, 2, 3 and 4) depending on the distribution of their Cys residues and a Cys-devoid regions (called spacers) characteristic of plant MTs.

A table including the principal aspects of the two latter classifications is included.

| Family | Name | Sequence pattern | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vertebrate | K-x(1,2)-C-C-x-C-C-P-x(2)-C | Mus musculus MT1 MDPNCSCTTGGSCACAGSCKCKECKCTSCKKCCSCCPVGCAKCAQGCVCKGSSEKCRCCA |

| 2 | Molluscan | C-x-C-x(3)-C-T-G-x(3)-C-x-C-x(3)-C-x-C-K | Mytilus edulis 10MTIV MPAPCNCIETNVCICDTGCSGEGCRCGDACKCSGADCKCSGCKVVCKCSGSCACEGGCTGPSTCKCAPGCSCK |

| 3 | Crustacean | P-[GD]-P-C-C-x(3,4)-C-x-C | Homarus americanus MTH MPGPCCKDKCECAEGGCKTGCKCTSCRCAPCEKCTSGCKCPSKDECAKTCSKPCKCCP |

| 4 | Echinoderms | P-D-x-K-C-V-C-C-x(5)-C-x-C-x(4)-C-C-x(4)-C-C-x(4,6)-C-C | Strongylocentrotus purpuratus SpMTA MPDVKCVCCKEGKECACFGQDCCKTGECCKDGTCCGICTNAACKCANGCKCGSGCSCTEGNCAC |

| 5 | Diptera | C-G-x(2)-C-x-C-x(2)-Q-x(5)-C-x-C-x(2)D-C-x-C | Drosophila melanogaster MTNB MVCKGCGTNCQCSAQKCGDNCACNKDCQCVCKNGPKDQCCSNK |

| 6 | Nematoda | K-C-C-x(3)-C-C | Caenorhabditis elegans MT1 MACKCDCKNKQCKCGDKCECSGDKCCEKYCCEEASEKKCCPAGCKGDCKCANCHCAEQKQCGDKTHQHQGTAAAH |

| 7 | Ciliate | x-C-C-C-x ? | Tetrahymena thermophila MTT1 MDKVNSCCCGVNAKPCCTDPNSGCCCVSKTDNCCKSDTKECCTGTGEGCKCVNCKCCKPQANCCCGVNAKPCCFDPNSGCCCVSKTNNCCKSD TKECCTGTGEGCKCTSCQCCKPVQQGCCCGDKAKACCTDPNSGCCCSNKANKCCDATSKQECQTCQCCK |

| 8 | Fungal 1 | C-G-C-S-x(4)-C-x-C-x(3,4)-C-x-C-S-x-C | Neurospora crassa MT MGDCGCSGASSCNCGSGCSCSNCGSK |

| 9 | Fungal 2 | --- | Candida glabrata MT2 MANDCKCPNGCSCPNCANGGCQCGDKCECKKQSCHGCGEQCKCGSHGSSCHGSCGCGDKCECK |

| 10 | Fungal 3 | --- | Candida glabrata MT2 MPEQVNCQYDCHCSNCACENTCNCCAKPACACTNSASNECSCQTCKCQTCKC |

| 11 | Fungal 4 | C-X-K-C-x-C-x(2)-C-K-C | Yarrowia lipolytica MT3 MEFTTAMLGASLISTTSTQSKHNLVNNCCCSSSTSESSMPASCACTKCGCKTCKC |

| 12 | Fungal 5 | --- | Saccharomyces cerevisiae CUP1 MFSELINFQNEGHECQCQCGSCKNNEQCQKSCSCPTGCNSDDKCPCGNKSEETKKSCCSGK |

| 13 | Fungal 6 | --- | Saccharomyces cerevisiae CRS5 TVKICDCEGECCKDSCHCGSTCLPSCSGGEKCKCDHSTGSPQCKSCGEKCKCETTCTCEKSKCNCEKC |

| 14 | Procaryota | K-C-A-C-x(2)-C-L-C | Synechococcus sp SmtA MTTVTQMKCACPHCLCIVSLNDAIMVDGKPYCSEVCANGTCKENSGCGHAGCGCGSA |

| 15 | Plant | [YFH]-x(5,25)-C-[SKD]-C-[GA]-[SDPAT]-x(0,1)-C-x-[CYF] | |

| 15.1 | Plant MTs Type 1 | C-X-C-X(3)- C-X-C-X(3)- C-X-C-X(3)-spacer-C-X-C-X(3)- C-X-C-X(3)- C-X-C-X(3) | Pisum sativum MT MSGCGCGSSCNCGDSCKCNKRSSGLSYSEMETTETVILGVGPAKIQFEGAEMSAASEDGGCKCGDNCTCDPCNCK |

| 15.2 | Plant MTs Type 2 | C-C-X(3)-C-X-C-X(3)- C-X-C-X(3)- C-X-C-X(3)-spacer- C-X-C-X(3)- C-X-C-X(3)- C-X-C-X(3) | Lycopersicon esculentum MT MSCCGGNCGCGSSCKCGNGCGGCKMYPDMSYTESSTTTETLVLGVGPEKTSFGAMEMGESPVAENGCKCGSDCKCNPCTCSK |

| 15.3 | Plant MTs Type 3 | --- | Arabidopsis thaliana MT3 MSSNCGSCDCADKTQCVKKGTSYTFDIVETQESYKEAMIMDVGAEENNANCKCKCGSSCSCVNCTCCPN |

| 15.4 | Plant MTs Type 4 or Ec | C-x(4)-C-X-C-X(3)-C-X(5)-C-X-C-X(9,11)-HTTCGCGEHC-

X-C-X(20)-CSCGAXCNCASC-X(3,5) |

Triticum aestivum MT MGCNDKCGCAVPCPGGTGCRCTSARSDAAAGEHTTCGCGEHCGCNPCACGREGTPSGRANRRANCSCGAACNCASCGSTTA |

| 99 | Phytochelatins and other non-proteinaceous MT-like polypeptides | --- | Schizosaccharomyces pombe γEC-γEC-γECG |

More data on this classification are discoverable at the Expasy metallothionein page.[8]

Secondary structure elements have been observed in several MTs SmtA from Syneccochoccus, mammalian MT3, Echinoderma SpMTA, fish Notothenia coriiceps MT, Crustacean MTH, but until this moment, the content of such structures is considered to be poor in MTs, and its functional influence is not considered.

Tertiary structure of MTs is also highly heterogeneous. While vertebrate, echinoderm and crustacean MTs show a bidominial structure with divalent metals as Zn(II) or Cd(II) (the protein is folded so as to bind metals in two functionally independent domains, with a metallic cluster each), yeast and prokaryotic MTs show a monodominial structure (one domain with a single metallic cluster). In yeast, the first 40 residues in the protein wrap around the metal by forming two large parallel loops separated by a deep cleft containing the metal cluster.[9] Although no structural data is available for molluscan, nematoda and Drosophila MTs, it is commonly assumed that the former are bidominial and the latter monodominial. No conclusive data are available for Plant MTs, but two possible structures have been proposed: 1) a bidominial structure similar to that of vertebrate MTs; 2) a codominial structure, in which two Cys-rich domains interact to form a single metallic cluster.

Quaternary structure has not been broadly considered for MTs. Dimerization and oligomerization processes have been observed and attributed to several molecular mechanisms, including intermolecular disulfide formation, bridging through metals bound by either Cys or His residues on different MTs, or inorganic phosphate-mediated interactions. Dimeric and polymeric MTs have been shown to acquire novel properties upon metal detoxification, but the physiological significance of these processes has been demonstrated only in the case of prokaryotic Synechococcus SmtA. The MT dimer produced by this organism forms structures similar to zinc fingers and has Zn-regulatory activity.

Metallothioneins have diverse metal-binding preferences, which have been associated with functional specificity. As an example, the mammalian Mus musculus MT1 preferentially binds divalent metal ions (Zn(II), Cd(II),...), while yeast CUP1 is selective for monovalent metal ions (Cu(I), Ag(I),...). Strictly metal-selective MTs with metal-specific physiological functions were discovered by Dallinger et al. (1997) in pulmonate snails (Gastropoda, Mollusca).[10] The Roman snail (Helix pomatia), for example, possesses a Cd-selective (CdMT) and a Cu-selective isoform (CuMT) involved in Cd detoxification and Cu regulation, respectively.[10] While both isoforms contain unvaried numbers and positions of Cys residues responsible for metal ligation, metal selectivity is apparently achieved by sequence modulation of amino acid residues not directly involved in metal binding (Palacios et al. 2011).[10][11]

A novel functional classification of MTs as Zn- or Cu-thioneins is currently being developed based on these functional preferences.

Function

The main biological function of metallothioneins is to maintain homeostasis of the essential metals zinc and copper, but metallothioneins also protect against metal toxicity and oxidative stress.[12]

Metal binding

Metallothionein has been documented to bind a wide range of metals including cadmium,[13] lead,[14] zinc, mercury, copper, arsenic, silver, etc. Metalation of MT was previously reported to occur cooperatively but recent reports have provided strong evidence that metal-binding occurs via a sequential, noncooperative mechanism.[15] The observation of partially metalated MT (that is, having some free metal binding capacity) suggest that these species are biologically important.

Metallothioneins likely participate in the uptake, transport, and regulation of zinc in biological systems. Mammalian MT binds three Zn(II) ions in its beta domain and four in the alpha domain. Cysteine is a sulfur-containing amino acid, hence the name "-thionein". However, the participation of inorganic sulfide and chloride ions has been proposed for some MT forms. In some MTs, mostly bacterial, histidine participates in zinc binding. By binding and releasing zinc, metallothioneins (MTs) may regulate zinc levels within the body. Zinc, in turn, is a key element for the activation and binding of certain transcription factors through its participation in the zinc finger region of the protein.[16][17] Metallothionein also carries zinc ions (signals) from one part of the cell to another. When zinc enters a cell, it can be picked up by thionein (which thus becomes "metallothionein") and carried to another part of the cell where it is released to another organelle or protein.[18] In this way thionein and metallothionein becomes a key component of the zinc signaling system in cells. This system is particularly important in the brain, where zinc signaling is prominent both between and within nerve cells. It also seems to be important for the regulation of the tumor suppressor protein p53.

Control of oxidative stress

Cysteine residues from MTs can capture harmful oxidant radicals like the superoxide and hydroxyl radicals.[19] In this reaction, cysteine is oxidized to cystine, and the metal ions which were bound to cysteine are liberated to the media. As explained in the Expression and regulation section, this Zn can activate the synthesis of more MTs. This mechanism has been proposed to be an important mechanism in the control of the oxidative stress by MTs. The role of MTs in reducing oxidative stress has been confirmed by MT Knockout mutants, but some experiments propose also a prooxidant role for MTs.

In mammalian cells, spontaneous mutagenesis is caused to a large extent by oxidative DNA damage, and the occurrence of such damage can be blocked by metallothionein.[20]

Metallothionein also plays a role in hematopoietic cell differentiation and proliferation, as well as prevention of apoptosis of early differentiated cells. Induced MT levels were adversely associated with sensitivity to etoposide-induced apoptosis, signifying that MT is a potential negative controller of apoptosis.[21]

Expression and regulation

Metallothionein gene expression is induced by a high variety of stimuli, as metal exposure, oxidative stress, glucocorticoids, Vitamin D, hydric stress, fasting, exercise, etc. Beta-hydroxylbutyration of histone proteins upregulates MT2.[22] The level of the response to these inducers depends on the MT gene. MT genes present in their promoters specific sequences for the regulation of the expression, elements as metal response elements (MRE), glucocorticoid response elements (GRE), GC-rich boxes, basal level elements (BLE), and thyroid response elements (TRE).[23][24]

Metallothionein and disease

Cancer

Because MTs play an important role in transcription factor regulation, defects in MT function or expression may lead to malignant transformation of cells and ultimately cancer.[25] Studies have found increased expression of MTs in some cancers of the breast, colon, kidney, liver, skin (melanoma), lung, nasopharynx, ovary, prostate, mouth, salivary gland, testes, thyroid and urinary bladder; they have also found lower levels of MT expression in hepatocellular carcinoma and liver adenocarcinoma.[26]

Evidence suggests that greater MT expression may cause resistance to chemotherapy.[27]

Autism

Heavy metal toxicity has been proposed as a hypothetical etiology of autism, and dysfunction of MT synthesis and activity may play a role in this. Many heavy metals, including mercury, lead, and arsenic have been linked to symptoms that resemble the neurological symptoms of autism.[28] However, MT dysfunction has not specifically been linked to autistic spectrum disorders. A 2006 study, investigating children exposed to the vaccine preservative thiomersal, found that levels of MT and antibodies to MT in autistic children did not differ significantly from non-autistic children.[29]

A low zinc to copper ratio has been seen as a biomarker for autism and suggested as an indication that the metallothionein system has been affected.[30]

Further, there is indication that the mother's zinc levels may affect the developing baby's immunological state that may lead to autism and could be again an indication that the metallothionein system has been affected.[31]

Role of Metallothionein in Cardiovascular disease

Metallothionein (MT) is an indirect redox balance regulator which regulates nuclear factor red blood cell 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) in the body. However, MT plays an important role in the anti-injury protection of the cardiovascular system, mainly in its inhibitory effect on ischemia-reperfusion injury. Also, the MT activation of the Nrf2 mediates intermittent hypoxia (IH) cardiomyopathy protection.[32]

Transgenic mice with a deletion of any Nrf2 gene (Nrf2-KO) are highly susceptible to the cardiovascular effects of intermittent hypoxia (IH) via cardiac oxidative damage, inflammation, fibrosis, and dysfunction.[32]

Moreover, the specific overexpression in cardiomyocytes of Nrf2 (Nrf2-TG) in transgenic mice[KC1] is impervious to cardiac oxidative damage, inflammation, fibrosis, and dysfunction caused by intermittent hypoxia (IH)[KC2] . In response to IH, Nrf2 and its downstream antioxidants are strongly MT-dependent Nrf2 and may [KC3] act as a compensatory response to IH exposure by up-regulating MT (downstream antioxidant target genes) to protect the heart.[32]

Prolonged exposure to IH reduces the binding of Nrf2 factor to the MT promoter gene, thereby inhibiting MT translation and expression. Moreover, a complex PI3K/Akt/GSK3B/Fyn signaling network provides cardio protection against IH when Nrf2 or MT is overexpressed in the heart. By activating the PI3K/Akt/GSK3B/Fyn signaling pathway, MT increaseNrf2 expression and transcriptional function in response to IH exposure. Although not yet proven, these effects suggest that it is possible to activate PI3K/Akt/GSK3B/Fyn dependent signaling pathways through cardiac MT overexpression to prevent chronic IH-induced cardiomyopathy and downregulation of Nrf2.[32]

Therefore, Nrf2 or MT may be a potential treatment to avoid chronic IH-induced cardiomyopathy.

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Symbol | Human metallothionein |

| PDB Code | 2FJ4 |

| Classification | Metal Binding Protein |

See also

References

- ↑ PDB: 2KAK; Peroza EA, Schmucki R, Güntert P, Freisinger E, Zerbe O (March 2009). "The beta(E)-domain of wheat E(c)-1 metallothionein: a metal-binding domain with a distinctive structure". Journal of Molecular Biology. 387 (1): 207–18. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.035. PMID 19361445.

- ↑ Sigel H, Sigel A, eds. (2009). Metallothioneins and Related Chelators (Metal Ions in Life Sciences). Vol. 5. Cambridge, England: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-84755-899-2.

- ↑ Margoshes M, Vallee BL (1957). "A cadmium protein from equine kidney cortex". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 79 (17): 4813–4814. doi:10.1021/ja01574a064.

- ↑ Felizola SJ, Nakamura Y, Arata Y, Ise K, Satoh F, Rainey WE, Midorikawa S, Suzuki S, Sasano H (September 2014). "Metallothionein-3 (MT-3) in the human adrenal cortex and its disorders". Endocrine Pathology. 25 (3): 229–35. doi:10.1007/s12022-013-9280-9. PMID 24242700. S2CID 39871076.

- ↑ Suhy DA, Simon KD, Linzer DI, O'Halloran TV (April 1999). "Metallothionein is part of a zinc-scavenging mechanism for cell survival under conditions of extreme zinc deprivation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (14): 9183–92. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.14.9183. PMID 10092590.

- ↑ Wang WC, Mao H, Ma DD, Yang WX (August 2014). "Characteristics, functions, and applications of metallothionein in aquatic vertebrates". Frontiers in Marine Science. 1: 34. doi:10.3389/fmars.2014.00034.

- ↑ Cherian MG (September 1994). "The significance of the nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of metallothionein in human liver and tumor cells". Environmental Health Perspectives. 102 (Suppl 3): 131–5. doi:10.2307/3431776. JSTOR 3431776. PMC 1567399. PMID 7843087.

- ↑ "Metallothioneins: classification and list of entries". www.uniprot.org.

- ↑ Peterson CW, Narula SS, Armitage IM (January 1996). "3D solution structure of copper and silver-substituted yeast metallothioneins". FEBS Letters. 379 (1): 85–93. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(95)01492-6. PMID 8566237.

- 1 2 3 Dallinger R, Berger B, Hunziker P, Kägi JH (1997). "Metallothionein in snail Cd and Cu metabolism". Nature. 388 (6639): 237–238. Bibcode:1997Natur.388..237D. doi:10.1038/40785. PMID 9230430. S2CID 4404470.

- ↑ Palacios O, Pagani A, Pérez-Rafael S, Egg M, Höckner M, Brandstätter A, Capdevila M, Atrian S, Dallinger R (January 2011). "Shaping mechanisms of metal specificity in a family of metazoan metallothioneins: evolutionary differentiation of mollusc metallothioneins". BMC Biology. 9 (4): 4. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-9-4. PMC 3033865. PMID 21255385.

- ↑ Sekovanić A, Jurasović J, Piasek M (2020). "Metallothionein 2A gene polymorphisms in relation to diseases and trace element levels in humans". Arhiv Za Higijenu Rada I Toksikologiju. 71 (1): 27–47. doi:10.2478/aiht-2020-71-3349. PMC 7837243. PMID 32597135.

- ↑ Freisinger E, Vašák M (2013). "Cadmium in Metallothioneins". Cadmium: From Toxicity to Essentiality. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 11. pp. 339–71. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5179-8_11. ISBN 978-94-007-5178-1. PMID 23430778.

- ↑ Wong DL, Merrifield-MacRae ME, Stillma MJ (2017). "Chapter 9. Lead(II) Binding in Metallothioneins". In Astrid S, Helmut S, Sigel RK (eds.). Lead: Its Effects on Environment and Health. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 17. de Gruyter. pp. 241–270. doi:10.1515/9783110434330-009. PMID 28731302.

- ↑ Krezel A, Maret W (September 2007). "Dual nanomolar and picomolar Zn(II) binding properties of metallothionein". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 129 (35): 10911–21. doi:10.1021/ja071979s. PMID 17696343.

- ↑ Huang M, Krepkiy D, Hu W, Petering DH (May 2004). "Zn-, Cd-, and Pb-transcription factor IIIA: properties, DNA binding, and comparison with TFIIIA-finger 3 metal complexes". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 98 (5): 775–85. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.01.014. PMC 3516448. PMID 15134923.

- ↑ Huang M, Shaw III CF, Petering DH (April 2004). "Interprotein metal exchange between transcription factor IIIa and apo-metallothionein". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 98 (4): 639–48. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.02.004. PMC 3535305. PMID 15041244.

- ↑ Palacios O, Atrian S, Capdevila, M (2011). "Zn- and Cu-thioneins: a functional classification for metallothioneins?". Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 16 (7): 991–1009. doi:10.1007/s00775-011-0827-2. PMID 21823038. S2CID 26786966.

- ↑ Kumari MV, Hiramatsu M, Ebadi M (August 1998). "Free radical scavenging actions of metallothionein isoforms I and II". Free Radical Research. 29 (2): 93–101. doi:10.1080/10715769800300111. PMID 9790511.

- ↑ Rossman TG, Goncharova EI. Spontaneous mutagenesis in mammalian cells is caused mainly by oxidative events and can be blocked by antioxidants and metallothionein. Mutat Res. 1998 Jun 18;402(1-2):103-10. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00287-x. PMID: 9675254

- ↑ Takahashi S (July 2012). "Molecular functions of metallothionein and its role in hematological malignancies". Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 5 (1): 41. doi:10.1186/1756-8722-5-41. PMC 3419633. PMID 22839501.

- ↑ Stubbs BJ, Koutnik AP, Volek JS, Newman JC (2021). "From bedside to battlefield: intersection of ketone body mechanisms in geroscience with military resilience". GeroScience. 43 (3): 1071–1081. doi:10.1007/s11357-020-00277-y. PMC 8190215. PMID 33006708.

- ↑ Klaassen CD, Liu J, Choudhuri S (1999). "Metallothionein: an intracellular protein to protect against cadmium toxicity". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 39: 267–94. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.267. PMID 10331085.

- ↑ Mostafa WZ, Hegazy RA (November 2015). "Vitamin D and the skin: Focus on a complex relationship: A review". Journal of Advanced Research. 6 (6): 793–804. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2014.01.011. PMC 4642156. PMID 26644915.

- ↑ Krizkova S, Fabrik I, Adam V, Hrabeta J, Eckschlager T, Kizek R (2009). "Metallothionein--a promising tool for cancer diagnostics". Bratislavske Lekarske Listy. 110 (2): 93–7. PMID 19408840.

- ↑ Cherian MG, Jayasurya A, Bay BH (December 2003). "Metallothioneins in human tumors and potential roles in carcinogenesis". Mutation Research. 533 (1–2): 201–9. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.07.013. PMID 14643421.

- ↑ Basu A, Krishnamurthy S (August 2010). "Cellular responses to Cisplatin-induced DNA damage". Journal of Nucleic Acids. 2010: 1–16. doi:10.4061/2010/201367. PMC 2929606. PMID 20811617.

- ↑ Drum DA (October 2009). "Are toxic biometals destroying your children's future?". Biometals. 22 (5): 697–700. doi:10.1007/s10534-009-9212-9. PMID 19205900. S2CID 31579963.

- ↑ Singh VK, Hanson J (June 2006). "Assessment of metallothionein and antibodies to metallothionein in normal and autistic children having exposure to vaccine-derived thimerosal". Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 17 (4): 291–6. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3038.2005.00348.x. PMID 16771783. S2CID 2843402.

- ↑ Faber S, Zinn GM, Kern JC, Kingston HM (May 2009). "The plasma zinc/serum copper ratio as a biomarker in children with autism spectrum disorders". Biomarkers. 14 (3): 171–80. doi:10.1080/13547500902783747. PMID 19280374. S2CID 205770002.

- ↑ Vela G, Stark P, Socha M, Sauer AK, Hagmeyer S, Grabrucker AM (2015). "Zinc in gut-brain interaction in autism and neurological disorders". Neural Plasticity. 2015: 972791. doi:10.1155/2015/972791. PMC 4386645. PMID 25878905.

- 1 2 3 4 Zhou S, Yin X, Jin J, Tan Y, Conklin DJ, Xin Y, et al. (November 2017). "Intermittent hypoxia-induced cardiomyopathy and its prevention by Nrf2 and metallothionein". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 112: 224–239. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.07.031. PMC 7453314. PMID 28778483.

Further reading

- Cherian MG, Jayasurya A, Bay BH (December 2003). "Metallothioneins in human tumors and potential roles in carcinogenesis". Mutation Research. 533 (1–2): 201–9. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.07.013. PMID 14643421.

_with_Cd-Cd_bond.jpg.webp)