Michael Davitt | |

|---|---|

_restored.png.webp) | |

| Born | 25 March 1846 Straide, County Mayo, Ireland |

| Died | 30 May 1906 (aged 60) Elphis Hospital, Dublin, Ireland |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Occupation(s) | Writer, lecturer, and journalist |

| Known for | Irish Land League activism |

| Political party | Irish Parliamentary Party Irish National Federation |

| Spouse | Mary Yore (m. 1886) |

| Children | 5, including Robert and Cahir |

Michael Davitt (25 March 1846 – 30 May 1906) was an Irish republican activist for a variety of causes, especially Home Rule and land reform. Following an eviction when he was four years old, Davitt's family migrated to England. He began his career as an organiser of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, which resisted British rule in Ireland with violence. Convicted of treason felony for arms trafficking in 1870, he served seven years in prison. Upon his release, Davitt pioneered the New Departure strategy of cooperation between the physical-force and constitutional wings of Irish nationalism on the issue of land reform. With Charles Stewart Parnell, he co-founded the Irish National Land League in 1879, in which capacity he enjoyed the peak of his influence before being jailed again in 1881.

Davitt travelled widely, giving lectures around the world, supported himself through journalism, and served as Member of Parliament (MP) for the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) during the 1890s. When the party split over Parnell's divorce, Davitt joined the anti-Parnellite Irish National Federation. His Georgist views on the land question put him on the left wing of Irish nationalism, and he was a vociferous advocate of alliance between the Radical faction of the Liberal Party and the IPP.

Early years

Michael Davitt was born in Straide, County Mayo, Ireland, on 25 March 1846 during the Great Famine. He was the third of five children born to Martin and Catherine Davitt,[1] tenant farmers of little means who spoke Irish as the family language.[2] Martin had been involved in the Irish nationalist Ribbon movement in the 1830s.[3] In 1850, when Michael was four years old, his family was evicted due to arrears in rent. Davitt later claimed that this event, which he remembered, had brought about all of the family's ills.[1][2] Like many other Irish people at the time, the family decided to emigrate to England.[2] They took a ship to Liverpool and walked to Haslingden, East Lancashire, where they settled.[2][4]

His parents both worked selling fruit and at other odd jobs. Martin, who was literate and could speak English, ran a night school in their home, which they shared with other Irish families. The family endured the anti-Irish sentiment of the English working class, which believed that Irish immigrants undercut wages.[2] Davitt began working at the age of nine as a labourer in a cotton mill.[1] Two years later, his right arm was entangled in a cogwheel and mangled so badly it had to be amputated ten days later. As was typical for the era, he did not receive any compensation.[2]

According to biographer Carla King, the accident helped save Davitt from a lifetime of mill drudgery. When he recovered from his operation, a local philanthropist, John Dean, helped to send him to a Wesleyan school.[2] In August 1861, at the age of 15, he found work in a local post office owned by Henry Cockcroft, who also ran a printing business. He joined the Mechanics' Institute and continued to read and study, attending lectures on various topics. The Chartist movement lasted longer in Lancaster than elsewhere, and Davitt later recalled that Chartist leader Ernest Charles Jones was the first Englishman Davitt had heard denounce landlordism in Ireland. Although he was on a path to be an "upwardly mobile working-class radical", in King's words, Davitt instead chose to join the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in 1865.[3]

Irish Republican Brotherhood

The IRB was a secret society that promoted the use of violence to end British rule in Ireland. At the time it was popular among working-class Irish emigrants,[1] and according to another IRB member, "every smart respectable young fellow" from the Irish community in Haslingden joined. Davitt enjoyed the approval of his parents and was soon elected leader of the local Rossendale chapter of about fifty IRB members. In February 1867, Davitt led fifty Fenians on a failed raid on Chester Castle to obtain arms for the planned Fenian Rising that took place later that year. He learned that the police had heard of the plan and were lying in wait and managed to extricate his men from the situation without being caught.[3] In 1868, he left Cockcroft's printing firm to work full-time for the IRB, as organising secretary and arms agent for England and Scotland, posing as a travelling salesman as cover.[1][3]

Although he was wanted by the authorities from 1867,[1] they did not grasp his importance to the IRB.[5] In 1869, authorities obtained a letter that Davitt had written to IRB member Arthur Forrester, urging him not to go through with the execution of a suspected informer. Believing that a direct order would not be effective, Davitt asked Forrester to wait until Davitt could obtain the permission of two members of the IRB council. He therefore appeared to approve of the murder. After intensive police investigation, Davitt was arrested at Paddington Station in London on 14 May 1870, while awaiting a delivery of arms. Tried at Old Bailey in July, Davitt was convicted of treason felony for arms trafficking in support of insurrection and sentenced to fifteen years of penal servitude.[1][5] He believed that he had had neither fair hearing nor adequate defence counsel.[1]

Imprisoned at Millbank, Dartmoor, and Portsmouth,[1] Davitt was held for months in solitary confinement and endured hard labour and poor rations that permanently damaged his health.[6] However, he frequently broke the prison rules and his main objection was that he was treated the same as criminals even though he considered himself a political prisoner. In 1872, he smuggled a letter out of the prison which was published in several newspapers and led to an inquiry by the Home Secretary into his allegations. Davitt was paroled on 19 December 1877, having served seven and a half years, following pressure from the Home Rule League for an amnesty for all Irish political prisoners.[1]

He and other freed prisoners were welcomed by Isaac Butt and the Political Prisoners Visiting Committee in London[7] and returned to a "heroes' welcome" in Ireland. Davitt published a book about his prison experience,[1] and began a campaign for the release of remaining Fenian prisoners. His popularity caused him to try his hand at writing and lecturing, which he discovered he had a talent for.[8] He also rejoined the IRB, and became a member of its Supreme Council representing Northern England. Nevertheless, the success of the amnesty movement led him to appreciate the value of political, rather than physical force, approaches to achieving Irish republican goals.[7] His experiences in prison made him a lifetime supporter of prison reform for humane conditions for all prisoners. This was in contrast to other Irish nationalists who had served prison time, who were only interested in the condition of "political" prisoners.[9]

Shortly before his arrest, Davitt had persuaded his family to emigrate to the United States. In July 1878, Davitt made a trip to visit them and raise money through a lecture tour to bring his mother and youngest sister back to Ireland (his father had since died). Upon his arrival in New York, he was welcomed by the United States-based republican organisation Clan na Gael and its leader, John Devoy. In its first such venture of the kind, the Clan organised Davitt's lecture tour, which lasted until December.[8] In meetings with Irish-American Fenians, Davitt developed the strategy called the "New Departure", an informal collaboration between the physical-force and parliamentary wings of Irish nationalism focusing on the land reform campaign.[10][11] This collaboration was cemented during a meeting on 1 June 1879 in Dublin between Davitt, Devoy, and Charles Stewart Parnell, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), which advocated Home Rule achieved via Parliament.[12][lower-alpha 1]

The Land War

.jpg.webp)

Agrarian unrest in the west of Ireland was sparked by the 1879 famine, a combination of heavy rains, poor yields and low prices that brought widespread hunger and deprivation. Davitt played a role in the organisation of several large-scale meetings in Mayo to agitate for land reform.[13] At one of the meetings, he called for the liberation of Ireland from "the land robbers who seized it".[1] On 16 August 1879, the Land League of Mayo was founded in Castlebar. On 21 October it was superseded by the Irish National Land League based in Dublin. Parnell was made its president[14] and Davitt was one of its secretaries.[15] Through the Land League, Davitt attained the pinnacle of his political influence and power from 1879 through 1881.[1]

The league adopted the slogan "the land for the people", which was vague enough to be acceptable to Irish nationalists across the political spectrum.[14] The runaway popularity of the Land League among Irish Catholics[lower-alpha 2] worried British authorities. On the other hand, Davitt's cooperation with Parnell angered the IRB, which expelled Davitt from its Supreme Council in May 1880, although he continued to be a member of the organisation.[1][16] One of the actions the Land League took during this period was the campaign of ostracism against the land agent Captain Charles Boycott in Lough Mask House outside Ballinrobe in the autumn of 1880. This campaign led to Boycott abandoning Ireland in December.[17]

In May 1880, following Parnell's tour of the United States, Davitt travelled there to raise funds for the Land League,[18] specifically for political action to free Irish peasants "from the humiliation of a beggar's position".[19] He attended the first convention of the Central Provisional Council of the American Land League, at which he was appointed secretary of the organisation. As secretary, Davitt was responsible for improving the Land League's organisation, helping set up local branches. For the thirteen weeks that Davitt was in the United States, he and Lawrence Walsh were effectively the only national leaders; they worked closely with Anna Parnell, who provided assistance.[20] While in the United States he toured the country giving speeches as far afield as San Francisco.[21]

The Liberal government responded to the land agitation with the Protection of Persons and Property Act 1881, an extension of previous Coercion Acts, which would enable the internment without trial of those suspected of involvement in the Land War.[22][23] In their fight against the act, the IPP MPs reached new heights of obstruction, but were ultimately unable to block it. It was Davitt's idea to set up a Ladies' Land League to continue their work when the male Land League leaders were arrested, as expected.[24] On 3 February 1881, Davitt's ticket of leave was rescinded;[25][26] he was arrested in Dublin and returned to Millbank Prison in England.[27] The IPP MPs protested so strongly in Parliament that thirty-six were expelled.[26][27] Almost a thousand people were arrested under the Coercion Act, but agrarian crime continued to increase.[25] In April, the government introduced the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881, which Liberal minister Joseph Chamberlain described as removing "the chief grievance" of the agitators by granting many of their demands:[28] fair rent, free sale, and fixity of tenure. As it fell short of peasant proprietorship, it was criticised as insufficient by the Land League, although Davitt later claimed that it had "struck a mortal blow at Irish landlordism".[29]

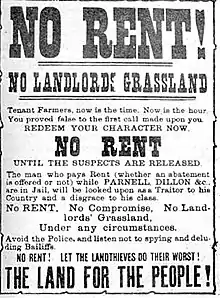

Davitt served most of his second term of incarceration at Portland Prison, under much better conditions than previously, owing to his fame and concern over his health. He was allowed books[27] and continued to study agrarian theory. He became enamoured of the ideas of Henry George and abandoned the idea of peasant proprietorship in favour of land nationalisation.[1] He also read many liberal thinkers, such as John Stuart Mill, Adolphe Thiers, Augustin Thierry, François Guizot, William Edward Hartpole Lecky, and Thomas Babington Macaulay.[30] In an 1882 by-election, he was elected Member of Parliament for Meath but was disqualified because he was in prison.[1] In October 1881, Parnell and other IPP leaders were also arrested. The Land League responded with the No Rent Manifesto on 18 October, urging tenant farmers not to pay rent until they were released.[23][29] Two days later, the British government banned the Land League.[31] Davitt and his allies were released from prison in May 1882, according to the Kilmainham Treaty agreed between the IPP and the Liberal Party. Some 130,000 tenants in arrears, who had been excluded from the rent-fixing authorised by the 1881 act, were given amnesty. In return, the IPP withdrew its support for agrarian agitation[32] and cancelled the No Rent Manifesto, bringing an end to the Land League.[33]

Travels and marriage

In June and July 1882, Davitt travelled to the United States on a lecture tour.[34] Upon his return, Davitt toured Britain alongside Henry George in a campaign for land nationalisation and an alliance between the British working class, Irish labourers, and tenant farmers sponsored by the New York-based Irish World.[35][36] Land nationalisation was extremely unpopular in Ireland,[37] and strongly opposed by the IPP, which was becoming defined as a party for the interests of Irish tenant farmers. After a meeting with Parnell in September 1882, Davitt agreed to set aside his support for the cause and resume cooperation with the IPP as a founder of the new Irish National League. The League included a few of Davitt's ideas, but was dominated by a conservative faction loyal to Parnell and emphasised Home Rule rather than further land reform. In addition, Parnell agreed to support a new organisation, the Irish Labour and Industrial Union, which aimed to help rural labourers acquire land and the franchise.[38] The union was later replaced by the Irish Democratic Trade and Labour Federation, over whose formation Davitt presided in 1890 with Michael Austin.[39][40] This organisation was later subsumed into D. D. Sheehan's Irish Land and Labour Association in 1894.[39]

With the demise of the Land League, agitation continued to be carried on by more extreme physical-force factions, such as the Fenian dynamite campaign, while the British government continued its crackdown. Davitt denounced both the bombings and the British government's excesses. As a result, he was arrested for sedition in February 1883 and served four months in jail, his last term in prison.[41] Believing that the Plan of Campaign—renewed agrarian agitation between 1886 and 1891—was against the Kilmainham Treaty, Davitt acceded to Parnell's request and did not involve himself in it.[42]

Davitt was a frequent visitor to Scotland, and became closely associated with the crofters' struggles in the Highlands and Islands. He urged the Irish immigrant population to integrate into the politics of their adopted country and in particular the infant Labour movement. Davitt worked closely with John Ferguson, the Irish leader in Glasgow who had been involved in the Crofters' War agitation by Highland tenant farmers in the early 1880s and later in the Irish-Radical political alliance that was the forerunner of the Scottish Labour Party.[43] Michael Daniel Jones and E. Pan Jones brought Davitt to Wales in 1886 to campaign for land reforms, although Davitt's radicalism made him unpopular among would-be reformers, who thought the movement ought to be managed by Welsh people.[44]

Davitt married an Irish-American woman, Mary Yore, on 30 December 1886 in Oakland, California; he had met her on his 1880 tour.[1][45] The couple settled in a cottage in Ballybrack, County Dublin, the only gift that Davitt ever accepted from his admirers.[46] They had five children – three boys and two girls, one of whom, Kathleen, died of tuberculosis aged seven in 1895.[47] One of their sons, Robert Davitt, became a TD (national legislator),[48] while another, Cahir Davitt, became President of the High Court.[49]

From 1880, when he published his first pieces in Irish World, Davitt made his income from journalism.[50][51] He had long aspired to edit his own paper, and founded the socialist penny weekly Labour World in September 1890. Davitt's paper covered a wide variety of topics, including foreign news, the plight of agricultural labourers, and women in the workplace. Although it was initially a success and sold 60,000 copies of its second edition, the Labour World stopped publishing the following year due to Davitt's illness, lack of funds, and other problems.[52]

When Parnell's extramarital affair with Katharine O'Shea was exposed in 1890, Davitt asked him to step down. He came to oppose Parnell's leadership for a number of reasons, including his belief that Parnell had misled him about the affair, insistence that the cause was more important than the individual, and fears that the revelations would harm the IPP–Liberal alliance.[53] When Parnell refused to step down, Davitt sided with the anti-Parnellite Irish National Federation and became one of Parnell's most vociferous critics, "reveal[ing] a rather unpleasant talent for personal invective" according to Boyce.[1] This put him in odd company, as the anti-Parnellites were dominated by social conservatives and proponents of Catholic clericalism, with whom Davitt had little in common. In his later writings he balanced criticism of Parnell's failings with appreciation for his accomplishments.[54]

Parliamentary career

Throughout the 1880s, Davitt had refused to stand for Parliament, believing that he could be of more use to the movement as an agitator. He also believed that the IPP put too much stake in parliamentary politics and that it could accomplish more working outside of the system. He had a visceral dislike for Westminster, which he referred to as "parliamentary pentitentiary", and was aware that entering into Parliament alienated his Fenian supporters abroad.[55] Davitt was elected for North Meath in the 1892 general election, but his election was overturned on petition because he had been supported by the Roman Catholic hierarchy. He stood unopposed for North East Cork at a by-election in February 1893, making his maiden speech in favour of the Home Rule Bill in April, which passed the House of Commons but was defeated in the Lords in September. The subsequent retirement of Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, who had come to sympathise with Home Rule, delayed the cause for another two decades. Having invested much of his own money into his 1892 campaign, Davitt had to declare bankruptcy in 1893 and resign from the House of Commons.[56]

For seven months in 1895, Davitt toured Australia and New Zealand to restore his finances.[57] The trip resulted in his second book, Life and Progress in Australasia (1896), with particular attention to governance and the situation of minorities such as Indigenous Australians and the Kanakas, Pacific Islanders brought in to work at very poor conditions in the colonies. Davitt noted that Western Australia had gotten its own Parliament with a population of some 45,000, while the five million people in Ireland had been denied Home Rule. What was then seven colonies had a substantial Irish population which had contributed to the Land League's efforts, providing an audience for Davitt's message.[58] While abroad, he was returned for both South Mayo and East Kerry; he chose to sit for Mayo as that was his birthplace.[59]

On many issues, Davitt supported the British Labour leader Keir Hardie and favoured the foundation of a Labour Party, but his commitment to the Liberal Party for the sake of Home Rule prevented him joining the new party, resulting in a breach with Hardie.[60] In Parliament, he pressed the Conservative government on its plans for improving the ongoing distress in western Ireland.[61] In 1898, Parliament sidestepped Home Rule by granting full democratic control of all local affairs to County and District Councils under the Local Government (Ireland) Act.[62] Davitt then co-founded, with William O'Brien, the United Irish League,[63] an organisation that advocated the redistribution of grazing land to small farmers. At the time O'Brien was politically isolated due to the controversial nature of land redistribution and Davitt was one of the only veterans willing to work with him.[64]

Final years and death

Following a speech in which he denounced the Second Boer War and the fact Ireland had to pay £10 million to the war effort despite opposing it, Davitt left the Commons for good on 26 October 1899 in protest of "the greatest infamy of the nineteenth century".[63] Obtaining commissions from William Randolph Hearst's New York American and the Irish paper Freeman's Journal, he travelled to South Africa to report on the war and lend support to the Boer cause. On 26 March 1900, he arrived in Pretoria and spent the next three months touring and visiting Irish units in the Boer army. Following the last session of the Volksraad, Davitt left the country as Lord Roberts' army advanced. The fact that the Boers were a "small nation of courageous fighters" facing off against the British Empire impressed Davitt. Nevertheless, of all his writings, The Boer Fight for Freedom (1902) has aged the least well; despite Davitt's concern for other indigenous peoples, he accepted the Boer narrative that Black Africans were "savages".[65]

The pro- and anti-Parnellite factions finally reconciled in 1900, but despite its explosive growth—the police estimated 989 branches and 100,000 members in August 1901—the United Irish League did not gain hegemony over the Irish nationalist movement. To combat the UIL, the British government introduced a new round of coercion and by September 1902 forty UIL leaders were jailed. Davitt and John Dillon were touring the United States to raise funds when the 1902 Land Conference was held, and by their return the Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903, masterminded by O'Brien, was a fait accompli.[66] Davitt criticised what he saw as the overly generous provisions for landlords to sell their estates to the tenants, the Irish Land Commission mediating to then collect land annuities instead of rents, on the grounds that the land rightfully belonged to the people. Later in 1906, after the Liberal Party came to power, his open support for their policy of state control of schooling, rather than denominational education, merged into a conflict between Davitt and the Catholic Church.[67] This would be the last controversy that Davitt was involved in.[68]

Davitt died in Elpis Hospital, Dublin on 30 May 1906, aged 60, of septicaemia arising from complications in a tooth extraction. As he requested, his funeral took place without any public notice and he was buried in Straide.[68][69] Nevertheless, The New York Times reported that Dublin businesses shuttered in respect while several MPs and "enormous crowds" attended the procession when his body was removed for transport. Additional mourners accompanied the train and a procession of almost one mile (two kilometres) followed the coffin from the station in Foxford, Mayo to Straide.[70] Davitt's estate was valued at £151;[1] in his will, he wrote "To all my friends I leave kind thoughts, to my enemies the fullest possible forgiveness and to Ireland the undying prayer for absolute freedom and independence, which it was my life's ambition to try and obtain for her."[71]

Views

Although a member of the IPP, Davitt kept his own counsel and his ideas frequently diverged from the party line.[72] In his politics, Davitt was more radical than Parnell and this brought them into conflict. Parnell saw land agitation primarily as a way to politicise Irish peasants, increase the popularity of the IPP, and advance the cause of Home Rule. In contrast, Davitt's highest priority was improving the lot of Irish farmers, especially the poorest.[73] While Parnell was a gifted politician, Davitt excelled as an organiser and activist.[74][75] An example of his greater militancy was his support for the Ladies' Land League after Parnell had denounced it in early 1882 and tried to cancel the No Rent Manifesto.[76] According to IPP MP T. P. O'Connor, Davitt was also suspicious of Parnell because the latter was a landowner.[77]

Davitt's views on land reform were based on a pre-capitalist understanding of access to land for subsistence farming to be a human right that superseded property rights, the so-called "unwritten law".[78] He believed that the landlord system was feudal in nature and had been imposed on Ireland by the British.[79] His ideas were also heavily shaped by his association with Henry George,[35] and he cited thinkers such as Herbert Spencer, Henry Fawcett and Bonamy Price in his writings advocating radical land reform.[30] Davitt came to agree with George that tenancy reform would not achieve "land for the people". In addition, even peasant proprietorship would fall short of this goal. Davitt foresaw that public funds spent on land purchases would never benefit landless labourers, and believed that the resulting smallholdings would eventually be consolidated into estates. Instead, from 1882, Davitt advocated for compulsory land nationalisation with compensation for current owners, so that all ground rent could be reclaimed by the state and used on public projects to benefit all citizens.[35] According to Marxist historian Peter Linebaugh, Davitt's ideas inspired James Connolly's "Celtic communism".[79]

Davitt's brand of Irish republicanism was heavily influenced by Chartism. For example, his 1878 manifesto had three main planks, the right to bear arms, self-government, and land reform to bring about "a system of small proprietorship similar to what at present obtains in France, Belgium, and Prussia". All three issues were advocated by Chartism.[80] Davitt pioneered a line of argument aimed at securing the support of the British working classes, which claimed that Home Rule for Ireland, by improving conditions there, would reduce Irish emigration to Britain and economic competition with British workers.[81] Due to his education in a Methodist school, Davitt accepted differences in creed.[82] He was opposed to the influence of clergy in politics, and was determined to perpetuate the inclusive nationalism of the Young Ireland movement, rather than let Irish nationalism transmute into a sectarian Catholic movement.[83] Davitt's left-wing views made him a natural ally of the Radical faction of the Liberal Party, and he supported the alliance between Home Rule supporters and the Liberal Party.[84] Unlike many other Irish nationalist leaders, Davitt was in favour of women's suffrage.[85]

According to biographer T. W. Moody, hatred of the British Empire and landlordism "was in his blood", but having grown up in England, Davitt held positive views on English people and understood the priorities of the working class in England.[82]

Violence

According to English historian Michael Kelly, Davitt's public renunciation of political violence made him "the Irish Republican Brotherhood's greatest apostate".[86] Davitt opposed the random use of force, such as by the Ribbon societies. On the other hand, he never fully renounced violence[16] and, according to Irish historian Paul Bew, was involved in smuggling arms for the IRB between his first release from prison and his expulsion from the IRB council in 1880.[16][87] Because he considered the landlord system inherently violent, Davitt believed it was moral to use force against it. However, for political reasons he presented the Land League as a peaceful movement and denied that his anti-landlord speeches and comments consisted of incitement to violence.[16] Davitt denounced agrarian crime as "a species of cowardly terrorism which would do irreparable injury to Ireland" and the Maamtrasna murders as "almost without a parallel for its atrocity in the annals of agrarian outrage".[88] However, the Land League leaders were not in control of their rank-and-file, who frequently used violence to intimidate others into withholding rent and to frighten landlords and their agents. Between 1879 and 1881, crimes related to the Land War rose from 25% to 58% of all crime in Ireland, without the leaders calling for an end to the agitation.[89] Davitt's "final break with the Fenians" did not come until the 1882 Phoenix Park murders of the Chief Secretary and Permanent Undersecretary for Ireland.[34]

Jews and Zionism

In 1903, Davitt travelled to Kishinev, Bessarabia in the Russian Empire as "special commissioner to investigate the massacres of the Jews" on behalf of Hearst's New York American, becoming one of the first foreign journalists to report on the Kishinev pogrom.[90] In his notes, Davitt recorded sharp criticism of what he saw as Jewish failure to defend themselves, given that there were many more Jews in the city than pogromists, but did not mention this aspect in his publications.[91] In his subsequent book, Within the Pale: The True Story of Anti-Semitic Persecutions in Russia (1903), Davitt declared his support for Zionism, believing that political independence was the only solution to the "Jewish Question" just as it was for the "Irish Question".[92][93] In 1898 at a meeting in Tonypandy, Davitt launched what Biagini (2007) called an "anti-Semitic tirade" against George Goschen, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, arguing that he "represented that class of bond-holders, and usurers, and mostly money-lenders for whom that infamous Egyptian war was waged".[94] Davitt opposed the 1904 Limerick boycott against the Limerick Jewish community organised by the Redemptorist priest John Creagh, stating in the Freeman's Journal that Limerick citizens would "not allow the fair name of Catholic Ireland to be sullied through an anti-Jewish crusade".[95][96]

While opposing "cowardly racial warfare" such as the Kishinev pogrom, Davitt announced that he was "resolutely in line with... [the] spirit and programme" of antisemitism when it stood "against the engineers of a sordid war in South Africa, or as the assailant of the economic evils of unscrupulous capitalism anywhere".[96][97] Henry Hyndman reported that Davitt believed Russia would be better off without any Jews.[96] Although Davitt recognised that Jews' business activity was related to their exclusion from many occupations, he nevertheless believed that Jews were racially predisposed to unscrupulous capitalism but also that the Jewish people were intellectually superior.[96][97] According to Irish historian Aidan Beatty, Davitt was not an antisemite, because his anti-Jewish statements coexisted with others which were supportive of Jews.[98] According to Stanford University historian Steven Zipperstein, Davitt "emerged as a folk hero among Jews" following his writings on Kishinev, with plays written about him in English and Yiddish.[99] Moody considers that Davitt's "passion for social justice... transcended nationality".[82]

Reception

The American abolitionist James Redpath considered Davitt "the William Lloyd Garrison of the anti-landlord movement".[100] Political scientist Eugenio Biagini views Davitt as "a social radical in the Tom Paine tradition" who was the "chief inspirer of the Land League and the greatest hero of popular nationalism".[101] Freeman's Journal lead writer James Winder Good hailed Davitt as the man whose "hammer strokes destroyed a system of land tenure, which for over three centuries had been the most powerful instrument in encompassing the economic degradation of the Irish people, and ensuring their subjugation to alien rule."[102] James Connolly considered Davitt "an unselfish idealist, who in his enthusiasm for a cause gave his name, and his services freely at the beck and call of men who despised his ideals".[72] According to Moody, in the estimation of his "innumerable" admirers, his faults were outweighed by "his great-heartedness, his self-sacrifice, and his invincible courage".[103] According to King, Davitt "may fairly be seen as a founding father of Irish democracy".[83]

Moody wrote that Davitt's habit of "reinterpreting his past actions and attitudes in accordance with altered conditions was partly the outcome of a longing for integrity in his political conduct".[104] An alternative interpretation is that this inconsistency is evidence of "Davitt's devious character", in the words of English historian Pamela Horn.[105]

The historical value of Davitt's books, such as the "deeply influential"[1] The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland (1904) has been hotly debated in the century since it was written. His view of Irish history was deeply shaped by his family's experiences during the Great Famine, and Davitt subscribed to the popular view that it was an "artificial famine" which the British government chose not to alleviate.[106] His version of the Land War, that it was an uncomplicated struggle between landlords and tenants, was widely accepted,[1] but has been complicated by later scholarship.[107] Moody, who disagreed with Davitt's conclusions, admitted that the book "contains a wealth of information", is reliable for facts, and far exceeds the work of his contemporaries.[108] In his obituary, The Times wrote that, "Anything more misleading than his presentation of what he calls The Boer Fight for Freedom cannot be imagined, unless it be his still wilder travesty of history, grotesquely named The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland."[109] An alternative view, of (among others) Conor Cruise O'Brien, historian of Parnellism, holds that Davitt's work is invaluable if partisan.[110]

At Straide in County Mayo, an old penal church was converted into a museum. In 2016, The Irish Times reported that the museum received no state funding and relied on visitor donations.[4] The Michael Davitt Bridge connects Achill Island to the mainland. Davitt inaugurated the first bridge in 1887, and it was replaced in 1947 but retained the name.[111] The centenary of Davitt's death saw the unveiling of a plaque at the Portree Hotel, Portree, Isle of Skye, commemorating his role in the Highland land agitation of the 1880s. The unveiling was carried out by his grandson, Fr. Tom Davitt.[112] On 29 May 2019, Dearcán Media's Irish-language documentary, Michael Davitt: Radacach (Michael Davitt: Radical) premiered on TG4.[113]

Works

- Cashman, D. B.; Davitt, Michael (1876). The Life of Michael Davitt: Founder of the National Land League. Glasgow: R. & T. Washbourne. OCLC 11246528. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- Davitt, Michael (1878). The Prison Life of Michael Davitt. Dublin: J. J. Lalore. OCLC 1029529296.

- Davitt, Michael (1882). . Glasgow: Cameron & Ferguson. OCLC 22251637.

- Davitt, Michael (1885). Leaves from a Prison Diary. London: Chapman. OCLC 494250416.

- Davitt, Michael (1898). Life and Progress in Australasia. London: Methuen. OCLC 1078978976.

- Davitt, Michael (1902). The Boer Fight for Freedom. London: Funk & Wagnalls. OCLC 23604776.

- Davitt, Michael (1903). Within the Pale, The True Story of Anti-Semitic Persecutions in Russia. New York: A. S. Barnes & Co. OCLC 17342804. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Davitt, Michael (1904). The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland: Or, The Story of the Land League Revolution. London: Harper & Bros. ISBN 9780716500438. OCLC 29085430.

- Davitt, Michael (2001). King, Carla (ed.). Collected Writings, 1868–1906. Bristol: Thoemmes/Edition Synapse. ISBN 9781855066489.

References

Notes

- ↑ It is disputed what was actually agreed to. Davitt maintained that there was no formal agreement, while Devoy claimed that the IPP had promised not to act against the IRB and made other concessions in exchange for Irish-American support.[12]

- ↑ Despite attempts to organise in Ulster, the Land League was not successful at appealing to Protestants due to its Irish nationalist rhetoric.[1]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Boyce 2004.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 King 2009, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 King 2009, p. 17.

- 1 2 Siggins 2016.

- 1 2 King 2009, p. 18.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 18–19.

- 1 2 King 2009, p. 21.

- 1 2 King 2009, p. 22.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 19.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Janis 2015, p. 24.

- 1 2 Janis 2015, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Janis 2015, pp. 10–11.

- 1 2 Janis 2015, p. 11.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 King 2009, p. 28.

- ↑ Moody 1982, p. 419.

- ↑ Janis 2015, p. 54.

- ↑ Janis 2015, p. 56.

- ↑ Janis 2015, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Janis 2015, p. 63.

- ↑ Biagini 2007, p. 132.

- 1 2 Janis 2015, p. 161.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 33–34.

- 1 2 Janis 2015, p. 164.

- 1 2 Bew 2007, p. 324.

- 1 2 3 King 2009, p. 34.

- ↑ Biagini 2007, p. 232.

- 1 2 King 2009, p. 35.

- 1 2 Biagini 2007, p. 108.

- ↑ Janis 2015, p. 166.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 39.

- ↑ Kelly 2006, p. 6.

- 1 2 King 2009, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 King 2009, p. 41.

- ↑ McBride 2006, p. 424.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 40.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 42–43.

- 1 2 King 2009, p. 53.

- ↑ Boyle 2003, p. 326.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 44.

- ↑ Bew 2007, p. 354.

- ↑ McBride 2006, pp. 421–422, 427.

- ↑ Jones 1997, pp. 457–459.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 32, 51.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 51.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 60, 76.

- ↑ Moore 1933.

- ↑ Moody 1982, p. 551.

- ↑ Zipperstein 2015, p. 372.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 31.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 10, 59.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 60, 77.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 59.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 60.

- ↑ Bew 1987, p. 45.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 10.

- 1 2 King 2009, p. 65.

- ↑ Bew 1987, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ King 2009, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Maume 1999, pp. 83, 225.

- 1 2 King 2009, p. 75.

- ↑ Marley 2007, p. 286.

- ↑ New York Times 1906, p. 9.

- ↑ The Sligo Champion 2006.

- 1 2 King 2009, p. 80.

- ↑ Janis 2015, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Janis 2015, p. 52.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 26.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ Janis 2015, p. 53.

- ↑ Jordan 1998, p. 148.

- 1 2 Linebaugh 2008, p. 138.

- ↑ Biagini 2007, p. 31.

- ↑ Biagini 2007, p. 71.

- 1 2 3 Moody 2002, p. 237.

- 1 2 King 2009, p. 81.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 48.

- ↑ King 2009, p. 36.

- ↑ Kelly 2006, p. 4.

- ↑ Bew 2007, p. 316.

- ↑ Biagini 2007, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Janis 2015, p. 163.

- ↑ Beatty 2017, p. 125.

- ↑ Zipperstein 2015, p. 369.

- ↑ Beatty 2017, pp. 126, 131.

- ↑ Marley 2007, p. 258.

- ↑ Biagini 2007, p. 73.

- ↑ Beatty 2017, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 4 Zipperstein 2015, p. 371.

- 1 2 Beatty 2017, p. 128.

- ↑ Beatty 2017, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Zipperstein 2015, p. 368.

- ↑ Janis 2015, p. 50.

- ↑ Biagini 2007, p. 109.

- ↑ Good, J. W. (1921). Michael Davitt. Dublin: Cumann Leigeacrai an Phobail. p. 3. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ↑ Moody 1982, p. 558.

- ↑ Moody 1982, p. 552.

- ↑ Horn 1983, p. 130.

- ↑ Jordan 2001, p. 144.

- ↑ Boyle 2003, p. 311.

- ↑ Moody 1982, p. 550.

- ↑ Jordan 2001, p. 141.

- ↑ Jordan 2001, p. 143.

- ↑ MacSweeney 2008, p. 95.

- ↑ Kenefick 2019.

- ↑ Northern Ireland Screen 2019.

Print sources

- Beatty, Aidan (2017). "Jews and the Irish nationalist imagination: between philo-Semitism and anti-Semitism". Journal of Jewish Studies. 68 (1): 125–128. doi:10.18647/3304/JJS-2017. Archived from the original on 22 September 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Bew, Paul (1987). Conflict and Conciliation in Ireland, 1890-1910: Parnellites and Radical Agrarians. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198227588.

- Bew, Paul (2007). Ireland: The Politics of Enmity 1789-2006. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198205555.

- Biagini, Eugenio F. (2007). British Democracy and Irish Nationalism 1876–1906. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139467568.

- Boyle, John W. (2003) [1983]. "A Marginal Figure: The Irish Rural Laborer". In Clark, Samuel; Donnelly, James S. (eds.). Irish Peasants: Violence and Political Unrest, 1780–1914. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 311–338. ISBN 9780299093747.

- Horn, Pamela (1983). "T. W. Moody: "Davitt and the Irish Revolution 1846-1882" (Book Review)". Irish Economic and Social History. 10: 130. doi:10.1177/033248938301000119. S2CID 165086462. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- Janis, Ely M. (2015). A Greater Ireland: The Land League and Transatlantic Nationalism in Gilded Age America. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299301248.

- Jones, J Graham (1997). "Michael Davitt, David Lloyd George and T. E. Ellis: the Welsh Experience". Welsh History Review. 18 (3): 450–482.

- Jordan, Donald (1998). "The Irish National League and the 'Unwritten Law': Rural Protest and Nation-Building in Ireland 1882–1890". Past & Present. Oxford University Press. 158 (158): 146–171. doi:10.1093/past/158.1.146. ISSN 0031-2746. JSTOR 651224.

- Jordan, Donald E. (2001). "Michael Davitt: Activist Historian". New Hibernia Review. 5 (1): 141–145. doi:10.1353/nhr.2001.0007. ISSN 1534-5815.

- Kelly, Matthew J. (2006). The Fenian Ideal and Irish Nationalism, 1882-1916. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843832041.

- King, Carla (2009). Michael Davitt. Dublin: University College Dublin Press. ISBN 9781910820964.

- Linebaugh, Peter (2008). "Review of Subversive Law in Ireland, 1879–1920: from 'Unwritten Law' to the Dáil Courts". Irish Economic and Social History. 35: 135–142. doi:10.7227/IESH.35.8. ISSN 0332-4893. JSTOR 24338511.

- MacSweeney, Tom (2008). Seascapes. Cork: Mercier Press. ISBN 9781856356008.

- Marley, Laurence (2007). Michael Davitt: Freelance Radical and Frondeur. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 9781846820663.

- Maume, Patrick (1999). The Long Gestation: Irish Nationalist Life, 1891-1918. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312225490.

- McBride, Terrance (2006). "John Ferguson, Michael Davitt and Henry George - Land for the People". Irish Studies Review. 14 (4): 421–430. doi:10.1080/09670880600984384. S2CID 144150236.

- Moody, Theodore William (1982). Davitt and Irish Revolution 1846–82. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198200697.

- Moody, Theodore William (2002). "Fenianism, Home Rule and the Land War". In Moody, Theodore William; Martin, Francis Xavier (eds.). The Course of Irish History. Lanham: Roberts Rinehart Publishers. ISBN 9781589790025.

- "Funeral of Michael Davitt; Enormous Crowds In Dublin – Many M.P.'s Present". The New York Times: 9. 3 June 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 96590501.

- Zipperstein, Steven J. (2015). "Inside Kishinev's Pogrom: Hayyim Nahman Bialik, Michael Davitt, and the Burdens of Truth" (PDF). In Freeze, ChaeRan Y.; Fried, Sylvia Fuks; Sheppard, Eugene R. (eds.). The Individual in History: Essays in Honor of Jehuda Reinharz. Waltham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press. ISBN 9781611687330. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

Web sources

- Boyce, D. George (2004). "Michael Davitt (1846–1906)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32747.

- Kenefick, William. "Cruelty, Grievance, Denial". Dublin Review of Books. Archived from the original on 15 August 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- "Michael Davitt: Radacach, TG4, Wednesday 29 May at 9.30pm". Northern Ireland Screen. 23 May 2019. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Moore, Séamus, Teachta Dála, Wicklow (19 July 1933). "Land Bill, 1933—Second Stage (Resumed).". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Ireland: Dáil Éireann.

- Siggins, Lorna (6 March 2016). "Museum for social reformer Michael Davitt survives on donations". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "Gurteen celebrates Michael Davitt at the spot where a social revolution begun". The Sligo Champion. 21 June 2006. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

Further reading

- Sheehy-Skeffington, Francis (1909). Michael Davitt: Revolutionary Agitator and Labour Leader. Boston: D. Estes. OCLC 7565774.

- Lane, Fintan; Newby, Andrew G., eds. (2009). Michael Davitt: New Perspectives. Dublin: Irish Academic Press. ISBN 9780716530428.

- King, Carla (2016). Michael Davitt After the Land League, 1882-1906. Dublin: University College Dublin Press. ISBN 9781906359928.

External links

- Michael Davitt Portrait Gallery: UCC Multitext Project in Irish History

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Michael Davitt

- The Michael Davitt Museum, Straide, Foxford, Co. Mayo