Mikhail Lermontov | |

|---|---|

Lermontov in 1837 | |

| Born | Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov 15 October [O.S. 3 October] 1814 Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | 27 July [O.S. 15 July] 1841 (aged 26) Pyatigorsk, Caucasus Oblast, Russian Empire |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, artist |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Period | Golden Age of Russian Poetry |

| Genre | Novel, poem, drama |

| Literary movement | Romanticism, pre-realism |

| Notable works | A Hero of Our Time |

| Signature | |

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov (/ˈlɛərməntɔːf, -tɒf/;[1] Russian: Михаи́л Ю́рьевич Ле́рмонтов; 15 October [O.S. 3 October] 1814 – 27 July [O.S. 15 July] 1841) was a Russian Romantic writer, poet and painter, sometimes called "the poet of the Caucasus", the most important Russian poet after Alexander Pushkin's death in 1837 and the greatest figure in Russian Romanticism. His influence on later Russian literature is still felt in modern times, not only through his poetry, but also through his prose, which founded the tradition of the Russian psychological novel.

Background

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov was born in Moscow into the Lermontov family, and he grew up in the village of Tarkhany (now Lermontovo in Penza Oblast).[2] His paternal family descended from the Scottish family of Learmonth, and can be traced to Yuri (George) Learmonth, a Scottish officer in the Polish–Lithuanian service who settled in Russia in the middle of the 17th century.[3][4][5] He had been captured by the Russian troops in Poland in the early 17th century, during the reign (1613–1645) of Mikhail Fyodorovich Romanov.[2] Family legend asserted that George Learmonth descended from the famed 13th-century Scottish poet Thomas the Rhymer (also known as Thomas Learmonth).[2] Lermontov's father, Yuri Petrovich Lermontov, like his father before him, followed a military career. Having moved up the ranks to captain, he married the sixteen-year-old Maria Mikhaylovna Arsenyeva, a wealthy young heiress of a prominent aristocratic Stolypin family. Lermontov's maternal grandmother, Elizaveta Arsenyeva (née Stolypina), regarded their marriage as a mismatch and deeply disliked her son-in-law.[6] On 15 October 1814, in Moscow where the family temporarily moved to, Maria gave birth to her son Mikhail.[7]

Early life

The marriage proved ill-suited and the couple soon grew apart. "There is no strong evidence as to what precipitated the quarrels they'd had. There are reasons to believe Yuri had grown tired of his wife's nervousness and frail health, and his mother-in-law's despotic ways," according to literary historian and Lermontov scholar Alexander Skabichevsky. An earlier biographer, Pavel Viskovatov, suggested the discord might have been caused by Yuri's affair with a young woman named Yulia, a lodger who worked in the house.[8] Apparently it was her husband's violent, erratic behavior and the resulting stresses that accounted for Maria Mikhaylovna's early demise. Her health quickly deteriorated and she developed tuberculosis and died on 27 February 1817, aged only 21.[7][2]

Nine days after Maria's death a final row broke out in Tarkhany and Yuri rushed away to his Kropotovo estate in Tula Governorate where his five sisters resided. Yelizaveta Arsenyeva launched a formidable battle for her beloved grandson, promising to disinherit him if his father took the boy away. Eventually the two sides agreed that the boy should stay with his grandmother until the age of 16. Father and son separated and, at the age of three, Lermontov began a spoilt and luxurious life with his doting grandmother and numerous relatives. This bitter family feud formed a plot of Lermontov's early drama Menschen und Leidenschaften (1830), its protagonist Yuri bearing strong resemblance to the young Mikhail.[4][6][9]

In June 1817 Yelizaveta Alekseyevna moved her grandson to Penza. In 1821 they returned to Tarkhany and spent the next six years there.[7] The doting grandmother spared no expense to provide the young Lermontov with the best schooling and lifestyle that money could buy. He received an extensive home education, became fluent in French and German, learned to play several musical instruments and proved a gifted painter.[5] While living with the grandmother, Mikhail hardly met with his father.

But the boy's health was fragile, he suffered from scrofula and rickets (the latter accounted for his bow-leggedness) and was kept under close surveillance of a French doctor, Anselm Levis. Colonel Capet, a Napoleon army prisoner-of-war who settled in Russia after 1812, was the boy's first, and best-loved governor.[10] A German pedagogue, Levy, who succeeded Capet, introduced Mikhail to Goethe and Schiller. He didn't stay for long and soon another Frenchman, Gendrot, replaced him, soon joined by Mr. Windson, a respectable English teacher recommended by the Uvarov family. Later Alexander Zinoviev, a teacher of Russian literature, arrived. The intellectual atmosphere in which Lermontov grew up resembled that experienced by Aleksandr Pushkin, though the domination of French had begun to give way to a preference for English, and Lamartine shared popularity with Byron.[5][11]

Looking for a better climate and treatment at the mineral springs for the boy, Arsenyeva twice, in 1819 and 1820, took him to the Caucasus where they stayed at her sister E. A. Khasatova's. In summer 1825, as the nine-year-old's health started to deteriorate, the extended family traveled south for the third time.[7] The Caucasus greatly impressed the boy, inspiring a passion for its mountains and stirring beauty. "Caucasian mountains for me are sacred", he wrote later. It was there that Lermontov experienced his first romantic passion, falling for a nine-year-old girl.[5][12]

Fearing that Lermontov's father would eventually claim his right to bring up his son, Arsenyeva strictly limited contact between the two, causing young Lermontov much pain and remorse. Despite all the pampering lavished upon him, and torn by the family feud, he grew up lonely and withdrawn. In another early autobiographical piece, "Povest" (The Tale), Lermontov described himself (under the guise of Sasha Arbenin) as an impressionable boy, passionately in love with all things heroic, but otherwise emotionally cold and occasionally sadistic. Having developed a fearful and arrogant temper, he took it out on his grandmother's garden as well as on insects and small animals ("with great delight, he would squash a hapless fly and bristled with joy when a stone he'd thrown would kick a chicken off its feet").[13] Positive influence came from Lermontov's German governess Christina Rhemer, a religious woman who introduced the boy to the idea of every man, even if that man was a serf, deserving respect. In fact, Lermontov's poor health served in a way as a saving grace, Skabichevsky argued, for it prevented the boy from further exploring the darker sides of his character and, more importantly, "taught him to think of things... seek pleasures that he couldn't find in the outer world, deep inside himself."[14]

Returning from his third trip to the Caucasus in August 1825, Lermontov began his regular studies with tutors in French and Greek, starting to read German, French and English authors' original texts.[5] In summer 1827 the 12-year-old for the first time travelled to his father's estate in Tula Governorate. In autumn of that year he and Yelizaveta Arsenyeva moved to Moscow.[4][15]

School years

After having received a year of private tutoring, in February 1829 the fourteen-year old Lermontov took exams and joined the 5th form of the Moscow University's boarding-school for the nobility's children.[16] Here his personal tutor was poet Alexey Merzlyakov, alongside Zinoviev, who taught Russian and Latin.[7] Under their influence the boy started to read a lot, making the best of his vast home library, which included books by Mikhail Lomonosov, Gavrila Derzhavin, Ivan Dmitriev, Vladislav Ozerov, Konstantin Batyushkov, Ivan Krylov, Ivan Kozlov, Vasily Zhukovsky, and Alexander Pushkin.[14] Soon he started editing an amateur student journal. One of his friends, his cousin Yekaterina Sushkova (Khvostova, in marriage) described the young man as "married to a hefty volume of Byron". Yekaterina had at one time been the object of Lermontov's affections and to her he dedicated some of his late 1820s poems, including "Nishchy" (The Beggar).[17] By 1829 Lermontov had written several of his well-known early poems. While "Kavkazsky Plennik" (Caucasian Prisoner), betraying strong Pushkin influence and borrowing from the latter, "The Corsair", "Prestupnik" (The Culprit), "Oleg", "Dva Brata" (Two Brothers), as well as the original version of "The Demon" were impressive exercises in Romanticism. Lord Byron remained the major source of inspiration for Lermontov, despite the attempts of his literary tutors, including Semyon Rayich, the head of the school's literature class, to divert him from that particular influence. The short poem "Vesna" (The Spring), published in 1830 by the amateur Ateneum magazine, marked his informal publishing debut.[5][15]

Along with his poetic skills, Lermontov developed an inclination towards poisonous wit and cruel, sardonic humor. His ability to draw caricatures was matched only by his ability to pin someone down with a well aimed epigram. In the boarding school Lermontov proved an exceptional student. He excelled at the 1828 examinations; he recited a Zhukovsky poem, performed a violin étude and won the first prize for his literary essay.[5] In April 1830 the University's boarding school was transformed into an ordinary gymnasium and Lermontov, like many of his fellow-students, promptly quit.[7][14]

Moscow University

In August 1830 Lermontov enrolled in Moscow University's philological faculty.[7] "Petty arrogance" (as Skabichevsky puts it) prevented him from joining any of the three radical students' circles (those led respectively by Vissarion Belinsky, Nikolai Stankevich and Alexander Hertzen). Instead he drifted towards an aristocracic clique, but even this cream of the Moscow's "golden youth" detested the young man for being too aloof, while still giving him credit for having charisma. "Everyone could see that Lermontov was obnoxious, rough and daring, and yet there was something alluring in his firm moroseness," fellow-student Wistengof admitted.[18]

Attending lectures faithfully, Lermontov would often read a book in the corner of the auditorium, and never took part in student life, making exceptions only for incidents involving grand-scale trouble-making. He took an active part in the notorious 1831 Malov scandal (when a jeering mob drove the unpopular professor out of the auditorium), but wasn't formally reprimanded (unlike Hertzen, who found himself incarcerated).[5][7] A year into his university studies, the final, tragic act of the family discord played itself out. Deeply affected by his son's alienation, Yuri Lermontov left Arsenieva's house for good, only to die a short time later of consumption.[19] His father's death under such circumstances was a terrible loss for Mikhail and is reflected in his poems "Forgive Me, Will We Meet Again?" and "The Terrible Fate of Father and Son". For some time he seriously considered suicide; tellingly, each of his early dramas Menschen und Leidenschaften (1830) and A Strange Man (1831) ends with a protagonist killing himself.[20] All the while, judging by his diaries, Lermontov, maintained a keen interest in European politics. Some of his University poems like "Predskazaniye" (The Prophecy) were highly politicised; the unfinished "Povest Bez Nazvaniya" (The Untitled Novel)'s theme was the outbreak of popular uprising in Russia. Several other verses written at the time – "Parus" (The Sail), "Angel Smerti" (Angel of Death) and "Ismail-Bei" – later came to be regarded among his best.[5]

In Lermontov's first year as a student no exams were held: the University closed for several months due to the outbreak of cholera in Moscow. In his second year Lermontov started to have serious altercations with several of his professors. Thinking little of his chances of passing the exams, he opted to leave, and on 18 June 1832, received the two-year-graduate certificate.[5][7]

1832–1837

In mid-1832 Lermontov, accompanied by grandmother, traveled to Saint Petersburg, with a view of joining the Saint Petersburg University's second-year course. This proved impossible and, unwilling to repeat the first year, he enrolled into the prestigious School of Cavalry Junkers and Ensign of the Guard, under pressure from his male relatives but much to Arsenyeva's distress. Having passed the exams, on 14 November 1832, Lermontov joined the Life-Guard Hussar regiment as a junior officer.[19][21] One of his fellow cadet-school students, Nikolai Martynov, the one whose fatal shot would kill the poet several years later, in his biographical "Notes" decades later described him as "the young man who was so far ahead of everybody else, as to be beyond comparison," a "real grown-up who'd read and thought and understood a lot about the human nature."[15]

The sort of glittering army career which tempted young noblemen of the time proved a challenge for Lermontov. Books there were a rarity and reading was frowned upon. Lermontov had to indulge mostly in physical competitions, one of which resulted in a horse-riding accident which left him with a broken knee that produced a limp.[19] Learning to enjoy the heady mix of drills and discipline, wenching and drinking sprees, Lermontov continued to sharpen the poisonous wit and cruel humour which would often earn him enemies.[21] "The time of my dreams has passed; the time for believing is long gone; now I want material pleasures, happiness that I can touch, happiness that can be bought with gold, that one can carry it in one's pocket as a snuff-box; happiness that beguiles only my senses while leaving my soul in peace and quiet," he wrote in a letter to Maria Lopukhina dated 4 August 1833.[19]

Concealing his literary aspirations from friends (relatives Alexey Stolypin and Nikolai Yuriev among them), Lermontov became an expert in producing scabrous verses (like "Holiday in Petergof", "Ulansha", and "The Hospital") which were published in a school's amateur magazine Shkolnaya Zarya (School-Years' Dawn) under monikers "Count Diarbekir" and "Stepanov". These pieces earned him much notoriety and, with a hindsight, caused harm, for when in July 1835 for the first time ever his poem "Khadji-Abrek" was published (in Biblioteka Dlya Chteniya, without its author's consent: Nikolai Yuriev took the copy to Osip Senkovsky and he furthered it to print), many refused to take the young author seriously.[5][21]

Upon his graduation in November 1834, Lermontov joined the Life-Guard Hussar regiment stationed near St. Petersburg in Tsarskoye Selo, where his flatmate was his friend Svyatoslav Rayevsky. Grandmother's lavish financial support (he had his personal chefs and coachmen) enabled Lermontov to plunge into a heady high-society mix of drawing-room gossip and ballroom glitter. "Sardonic, caustic and smart, brilliantly intelligent, rich and independent, he became the soul of the high society and the leading spirit in pleasure trips and sprees," Yevdokiya Rostopchina remembered.[22] "Extraordinary, how much youthful energy and precious time had Lermontov managed to spare upon wanton orgies and base love-making, without seriously damaging his physical and moral strength", biographer Skabichevsky marvelled.[22]

By now Lermontov had learnt to lead a double life. Still keeping his passions secret, he took a keen interest in Russian history and medieval epics, which would be reflected in The Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov and Borodino, as well as a series of popular ballads. During what he later referred to as "four wasted years" he finished "Demon", wrote Boyarin Orsha, The Tambov Treasurer's Wife and Masquerade, his best-known drama. Through Rayevsky he became acquainted with Andrey Krayevsky, then the editor of Russky Invalid's literary supplement, in a couple of years' time to become the editor of the influential journal Otechestvennye Zapiski.[5]

Death of the Poet

The death of Pushkin, who, as it was generally suspected, had fallen victim to an intrigue, ignited Russian high society. Lermontov, who himself never belonged to the Pushkin circle (there is conflicting evidence as to whether he'd met the famous poet at all), became especially vexed with Saint Petersburg dames' sympathizing with D'Anthès, a culprit whom he even considered challenging to a duel.[5]

Outraged and agitated, the young man found himself on the verge of nervous breakdown. Arsenyeva sent for Arendt, and the famous doctor who had spent with Pushkin his last hours related to Lermontov the exact circumstances of what had happened. The poem Death of the Poet, its final part written impromptu, in the course of several minutes, was spread around by Rayevsky and caused uproar. The last 16 lines of it, explicitly addressed to the inner circles at the court, all but accused the powerful "pillars" of Russian high-society of complicity in Pushkin's death. The poem portrayed that society as a cabal of self-interested venomous wretches "huddling about the throne in a greedy throng", "the hangmen who kill liberty, genius, and glory" about to suffer the apocalyptic judgment of God.[23]

The poem propelled Lermontov to an unprecedented level of fame. Zhukovsky hailed the "new powerful talent"; popular opinion greeted him as "Pushkin's heir". D'Anthes, still under arrest, felt so piqued he was now himself prepared to challenge the upstart to a duel. Alexander von Benckendorff, a distant relative of Arsenyeva's and the founding head of the Tsar's Gendarmes and of his secret police,[19] was willing to help her grandson out but still had no choice but to report the incident to Nicholas I, who, as it turned out, had already received a copy of the poem (subtitled "The Call for the Revolution", from an anonymous sender). The authorities arrested Lermontov, on 21 January he found himself in the Petropavlovskaya fortress and on 25 February got banished as a cornet to the Nizhegorodsky dragoons regiment to the Caucasus.[7][24] During the investigation, in an act he considered cowardice, Lermontov faulted his friend, Svyatoslav Rayevsky, and as a result the latter suffered a more severe punishment than Lermontov did: was deported to the Olonets Governorate for two years to serve in a lowly clerk's position.[5][19][23]

First exile

In the Caucasus Lermontov found himself quite at home. The stern and gritty virtues of the mountain tribesmen against whom he had to fight, no less than the scenery of the rocks and of the mountains themselves, were close to his heart. The place of his exile was also the land he had loved as a child. Attracted to the nature of the Caucasus and excited by its folklore, he studied the local languages (such as Kumyk), wrote some of his most splendid poems and painted extensively. "Good people are here aplenty. In Tiflis, especially, people are very honest... The mountain air acts like balsam for me, all spleen has gone to hell, the heart starts beating, the chest heaves," Lermontov wrote to Rayevsky. By the end of the year he had travelled all along the Caucasian line, from Kizlyar Bay to Taman Peninsula, and visited central Georgia.[5]

Lermontov's first Caucasian exile was short: due to the intercession of General Benckendorff. The poet was transferred to the Grodno cavalry regiment based at Nizhny Novgorod. His voyage back was a prolonged one, he made a point of staying wherever he was welcome. In Shelkozavodskaya Lermontov met A. A. Khastatov (his grandmother's sister's son), a man famous for his bravery, whose stories were later incorporated into A Hero of Our Times. In Pyatigorsk he had talks with poet and translator Nikolai Satin (a member of Herzen and Ogaryov circle) and with some of the Decembrists, notably with the poet Alexander Odoyevsky (with whom, judging by "In Memoriam", 1839, he became quite close); in Stavropol became friends with Dr. Mayer who served as a prototype for Doctor Werner (a man Pechorin meets in "town S."). In Tiflis he drifted towards a group of Georgian intellectuals led by Alexander Chavchavadze, Nina Griboyedova's father.[5]

The young officer's demeanor did not enchant everybody, though, and at least two of the Decembrists, Nikolai Lorer and Mikhail Nazimov, later spoke of him quite dismissively. Nazimov wrote years later:

Lermontov often visited us and talked of all sort of things, personal, social and political. I have to say, we hardly understood each other... We were unpleasantly surprised by the chaotic nature of his views, which were rather vague. He appeared to be a low-brow realist, unwilling to let his imagination fly, which was strange, considering how high his poetry soared on its mighty wings. He mocked some of the government's reforms – the ones we couldn't even dream of in our poor youth. Certain essays, promoting the most progressive European ideas which we were so enthusiastic about, – for who could have ever thought it possible for such things to be published in Russia? – left him cold. When approached with a straightforward question, he either kept silent or tried to get away with some sarcastic remark. The more we knew him, the more difficult it was for us to take him seriously. There was a spark of original thought in him, but he was still very young.[25]

Lermontov's journey to Nizhny took four months. He visited Yelizavetgrad, then stayed in Moscow and Saint Petersburg to enjoy himself at dancing parties and to revel in his immense popularity. "Lermontov's deportation to the Caucasus has made a lot of fuss and turned him into a victim, which did a lot to whip up his fame as a poet. People consumed his Caucasian poems greedily... On return he was met with enormous warmth in the capital and hailed as heir to Pushkin," wrote poet Andrey Muravyov.[5]

.jpg.webp)

Warmly welcomed at the houses of Karamzin, Alexandra Smirnova, Odoyevsky and Rostoptchina, Lermontov entered the most prolific phase of his short literary career. In 1837–1838 Sovremennik published humorous lyrical verses and two longer poems, "Borodino" and "Tambovskaya Kaznatcheysha" (A Treasurer Dame from Tambov), the latter severely cut by censors. Vasily Zhukovsky's letter to Minister Sergey Uvarov made possible the publication of "Pesn Kuptsa Kalashnikova" (The Song of Merchant Kalashnikov), a historical poem which the author initially sent to Krayevsky in 1837 from the Caucasus, only to be thwarted by censors. His observations of the aristocratic milieu, where fashionable ladies welcomed him as a celebrity, occasioned his play Masquerade (1835, first published in 1842). His doomed love for Varvara Lopukhina (b. Varvara Alexandrovna Lopukhina) was recorded in the novel Princess Ligovskaya (1836), which remained unfinished.[7] In those days Lermontov also took part in gathering and sorting out Pushkin's documents and unpublished poems.[5]

A Hero of Our Time

In February 1838, Lermontov arrived at Novgorod to join his new regiment.[7] In less than two months time, though, Arsenyeva ensured his transfer to the Petersburg-based Hussars Guard regiment. At this point, in Petersburg, Lermontov started working on A Hero of Our Time, a novel which later earned him recognition as one of the founding fathers of Russian prose.[5]

In January 1839 Andrey Krayevsky, now at the helm of Otechestvennye Zapiski, invited Lermontov to become a regular contributor. The magazine published two parts of the novel, "Bela" and "The Fatalist", in issues 2 and 4, respectively, the rest of it appeared in print during 1840 and earned the author widespread acclaim.[7] The partially autobiographical story, describing prophetically a duel like the one in which he would eventually lose his life, consisted of five closely linked tales revolving around a single character, a disenchanted, bored and doomed young nobleman. Later it came to be considered a pioneering classic of Russian psychological realism.[5][26]

Second exile

.jpg.webp)

Shallow pleasures offered by Saint Petersburg's high society had started to wear Lermontov down, his bad temper growing even worse. "What an extravagant man he is. Looks like he's heading for the imminent catastrophe. Insolent to a fault. Dying of boredom, getting vexed by his own frivolousness but having no will to break free from these surroundings. A strange kind of man," wrote Alexandra Smirnova, the lady-in-waiting and Saint Petersburg fashionable salon hostess.[15]

Lermontov's popularity at the salons of Princess Sofija Shcherbatova and of Countess Emilie Musin-Pushkina caused a lot of ill feeling among men vying for attention of these two most popular Petersburg society girls of the time.[7] In early 1840 Lermontov insulted one of these men, Ernest de Barante, the son of the French ambassador, in the presence of Shcherbatova. De Barante issued a challenge. The duel took place almost at the exact spot where Pushkin had received his fatal wound by Tchernaya Retchka. Lermontov found himself slightly injured, then arrested and jailed. His visitors in jail included Vissarion Belinsky, an avid admirer of Lermontov's poetry who, like many, continued to have problems with making sense of his dual personality and incongruous, difficult character.[5]

Due to the patronage of the Guard's Commander, Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich, Lermontov received only a mild punishment; the Grand Duke chose to interpret the de Barante incident as a feat for "a Russian officer who came up to champion the honour of the Russian army". With the Tsar's initial demand for three months' imprisonment dropped, Lermontov went back to exile in the Caucasus, to the Tengin infantry regiment. In Karamzin's house where his friends gathered to say farewells, he churned out an ad lib, "Tuchi nebesnye, vechnye stranniki" (Heavenly clouds, eternal travelers...). It made its way as a final entry into Lermontov's first book of verse, published by Ilya Glazunov & Co in October 1840, and became one of his best-loved short poems.[27]

In early May 1840 Lermontov left Saint Petersburg, but arrived at Stavropol only on 10 June, having spent a whole month in Moscow, visiting (among other people) Nikolai Gogol, to whom he recited his then-new poem Mtsyri. On arrival, Lermontov re-joined the Army as part of General Galafeyev's fighting unit on the left flank of the Caucasian front. The left flank had the mission of disarming the Chechen fighters led by Imam Shamil and of protecting the newly formed Russian Cossack settlement between the Kuban and Laba rivers. In early July the regiment entered Chechnya and went into action. Lermontov (according to the official report) "has been charged with the commandment of a Cossack troopers' unit whose duty it was to head into the enemy first". He became immensely popular with his men, whom regular army officers referred to as "the international gang of reckless thugs".[7]

Among officers Lermontov had his admirers and detractors. Generals Pavel Grabbe and Apollon Galafeyev both praised the young man for his reckless bravery. According to Baron Rossilyon, though, "Lermontov was an unpleasant and scornful man, always eager to seem special. He boasted his bravery – the one thing one was not supposed to be that proud of in the Caucasus, where bravery was business as usual. He led the gang of dirty thugs who, without ever using firearms, charged Chechen auls, led partisan wars and were calling themselves 'the Lermontov army'."[7]

In July 1840 the Russian army got involved in a fierce battle at the Gekha forest. There Lermontov distinguished himself in hand-to-hand combat at the Battle of the Valerik River (11 July 1840), the basis for his poem Valerik. "Lermontov's duty was to lead our forefront storm troopers and inform the headquarters of the advancement, which in itself was perilous since the enemy was everywhere around, in the forest and in the bushes. But this officer, defying danger, did an excellent job; he showed great courage and was always amongst those who'd break into the enemy lines first," General Galafeyev informed General Grabbe on 8 October 1840.[7][27]

In early 1841 Arsenyeva received permission from the Minister of Defense, Count Kleinmichel, for Lermontov to visit Saint Petersburg. "Those three or four months he spent in the capital were, I think, the happiest time of his life. Received quite ecstatically by the high society, each morning he produced some beautiful verse and hasted to recite it to us in the evening. In this warm atmosphere good humour awoke in him again, he was always coming up with new jokes and pranks, making us all laugh for hours on end," Yevdokiya Rostopchina remembered.[7]

By the time both A Hero of Our Time and Poems by M.Y. Lermontov had been published, Lermontov, according to Skabichevsky, started to treat his poetic mission seriously. Looking for an early retirement that would have enabled him to start a literary career, he was making plans for his own literary journal which wouldn't follow European trends, unlike (in Lermontov's view) Otechestvennye Zapiski. "I've learnt a lot from Easterners and I am eager to delve deeper into the depth of an Eastern mindset, which remains a mystery not only to us, but to an Easterner himself. The East is a bottomless well of revelations," Lermontov was telling Krayevsky.[28]

It soon became clear that for an early retirement there was no hope. Besides, despite General Grabbe's insistence, Lermontov's name had been dropped from the list of officers eligible for awards. In February 1841 an incident at a ball launched by Countess Alexandra Vorontsova-Dashkova (when Lermontov involuntarily snubbed the Tsar's two daughters) caused concern among the imperial family and in the high military ranks. It transpired that upon his arrival in February Lermontov had failed to report to his commanding officer, as was required, going instead to a ball – a grievous breach for someone serving under condition of punishment.[19] In April Count Kleinmichel issued an order for him to leave the city in 24 hours and join his regiment in the Caucasus. Lermontov approached a seer (the same Gypsy woman who'd predicted Pushkin's death "from a white man's hand") and asked if the time would ever come when he'd be allowed to retire. "You will get your retirement, but of such a kind after which you won't ask for more," she responded, which made Lermontov laugh heartily.[7][28]

Death

After visiting Moscow (where he produced no fewer than eight poetic pieces of invective aimed at Benckendorff), on 9 May 1841, Lermontov arrived to Stavropol, introduced himself to general Grabbe and asked for permission to stay in the town. Then, on a whim, he changed his course, found himself in Pyatigorsk and sent his seniors a letter informing them of his having fallen ill. The regiment's special commission recommended him treatment at Mineralnye Vody. What he did instead was embark upon the several weeks' spree. "In the mornings he was writing, but the more he worked, the more need he felt to unwind in the evenings," Skabichevsky wrote. "I feel I'm left with very little of my life," the poet confessed to his friend A. Merinsky on 8 July, a week before his death.[7]

In Pyatigorsk Lermontov enjoyed himself, feeding on his notoriety of a social misfit, his fame as a poet second only to Pushkin and his success with A Hero of Our Time. Meanwhile, in the same salons his Cadet school friend Nikolai Martynov, dressed as a native Circassian, wore a long sword, affected the manners of a romantic hero not unlike Lermontov's Grushnitsky character. Lermontov teased Martynov mercilessly until the latter couldn't stand it anymore. On 25 July 1841, Martynov challenged his offender to a duel.[19] The fight took place two days later at the foot of Mashuk mountain. Lermontov allegedly made it known that he was going to shoot into the air. Martynov was the first to shoot and he aimed straight into the heart, killing his opponent on the spot.[7] On 30 July Lermontov was buried, without military honours, thousands of people attended the ceremony.

In January 1842, the Tsar issued an order allowing the coffin to be transported to Tarkhany, where Lermontov was laid to rest at the family cemetery. Upon receiving the news his grandmother Elizaveta Arsenyeva suffered a minor stroke. She died in 1845. Many of Lermontov's verses were discovered posthumously in his notebooks.[29]

Private life

Mikhail Lermontov was a romantic who seemed to be continuously struggling with strong passions. Not much is known about his private life, though in verses dedicated to loved ones his emotional strife seems to have been exaggerated, while rumours concerning his real life adventures were unreliable and occasionally misguided.[5]

Lermontov fell in love for the first time in 1825, while at the Caucasus, a girl of nine being the object of his desires. Five years later he wrote about it with great seriousness, seeing this early awakening of romantic feelings as a sign of his own exclusiveness. "So early in life, at ten! Oh, this mystery, this Paradise Lost, it will be tormenting my mind till the very grave. Sometimes I feel funny about it and am ready to laugh at this first love of mine, but more often I'd rather cry," the 15-year-old wrote in a diary. "Some people, like Byron, think early love is akin to the soul prone to fine arts, but I suppose this is the sign of soul that's got much music in it," added the young man for whom the English poet was an idol.[30]

At sixteen Lermontov fell in love with Yekaterina Sushkova (1812–1868), a friend of his cousin Sasha Vereshchagina, whom he often visited in Srednikovo village. Yekaterina failed to take her suitor seriously and in her "Notes" described him thus:

At Sashenka [Vereshchagina]'s I often met her cousin, a clumsy bow-legged boy of 16 or 17, with reddened eyes, which were clever and expressive nevertheless, who had a turned-up nose and caustic sneer... Everybody was calling him just Michel and so did I, never caring about his second name. Assigned to be my 'errand boy' he was carrying my hat, umbrella and gloves, leaving them behind from time to time... Both Sashenka and I, while giving him credit for his intelligence, still treated him like a baby which drove him mad. Trying to be perceived as a serious young man, he recited Pushkin and Lamartine and never parted with a huge volume of Byron."[17]

Several 1830–31 poems by Lermontov were dedicated to Sushkova, among them "Nishchy" (The Beggar Man) and "Blagodaryu!, Zovi nadezhdu snovidenyem" (Thank you! To call the hope a dream...).

_Natalia_Fedorovna.jpg.webp)

In 1830 Lermontov met Natalya Ivanova (1813–1875), daughter of a Moscow playwright Fyodor Ivanov and had an affair with her, but little is known about it or why it ended. Judging by thirty or so poems addressed to "N.F.I", she chose a man who was older and richer, much to the distress of young Lermontov who took this as a 'betrayal'.[7]

While in the University 16-year-old Lermontov passionately fell in love with another cousin of his, Varvara Lopukhina" (also sixteen at the time). The passion was said to be reciprocal but, pressed by her family, Varvara went on to marry Nikolai Bakhmetyev a wealthy 37-year-old aristocrat. Lermontov was "astounded and heartbroken".[5]

Having graduated the Saint Petersburg cadet school, Lermontov embarked upon the easy-going lifestyle of a reckless young hussar, as he imagined it should be. "Mikhail, having found himself the very soul of the high society, liked to entertain himself by driving young women mad, feigning love for several days, just in order to upset matches," his friend and flatmate Alexey Stolypin wrote.[15]

In December 1834 Lermontov met his old sweetheart Yekaterina Sushkova at a ball in Saint Petersburg and decided to have a revenge: first he seduced, then, after a while dropped her, making the story public. Relating the incident in a letter to cousin Sasha Vereshchagina, he blatantly boasted about his newly found reputation of a 'Don Juan' which he's been apparently craving for. "I happened to hear several of Lermontov's victims complaining about his treacherous ways and couldn't restrict myself from openly laughing at the comic finales he used to invent for his vile Casanova feats," obviously sympathetic Yevdokiya Rostopchina recalled.

By 1840 Lermontov had sickened of his own reputation of a womanizer and a cruel heartbreaker, hunting for victims at balls and parties and leaving them behind devastated. Some of the stories were myth, like the one concerning the French author Adèle Hommaire de Hell; well-publicised at the time (and related at some length by Skabichevsky) it was proved later to have never happened.

Lermontov's love for Lopukhina (Bakhmetyeva) proved to be the only deep and lasting feeling of his life. His unfinished drama Princess Ligovskaya was inspired by it, as well as two characters in A Hero of Our Time, Princess Mary and Vera.[7] In his 1982 biography John Garrard wrote: "The symbolic relationship between love and suffering is of course a favorite Romantic paradox, but for Lermontov it was much more than a literary device. He was unlucky in love and believed he always would be: fate had ordained it."[19]

Works

In his lifetime, Mikhail Lermontov published only one slender collection of poems (1840). Three volumes, much mutilated by censorship, were published a year after his death in 1841. Yet his legacy – more than 30 large poems, and 600 minor ones, a novel and 5 dramas – was immense for an author whose literary career lasted just six years.[15]

Inspired by Lord Byron, Lermontov started to write poetry at the age of 13. His late 1820s poems like "The Corsair", "Oleg", "Two Brothers", as well as "Napoleon" (1830), borrowed somewhat from Pushkin, but invariably featured a Byronic hero, an outcast and an avenger, standing firm and aloof against the world.[5]

In the early 1830s Lermontov's poetry grew more introspective and intimate, even diary-like, with dates often serving for titles. But even his love lyric, addressed to Yekaterina Sushkova or Natalya Ivanova, could not be relied upon as autobiographical; driven by fantasies, it dealt with passions greatly hypertrophied, protagonists posing high and mighty in the center of the Universe, misunderstood or ignored.[5][15]

In 1831 Lermontov's poetry ("The Reed", "Mermaid", "The Wish") started to get less confessional, more ballad-like. The young author, having found taste for plots and structures, was trying consciously to rein in his emotional urge and master the art of storytelling. Critic and literature historian D.S. Mirsky regards "The Angel" (1831) as the first of Lermontov's truly great poems, calling it "arguably the finest Romantic verse ever written in Russian." At least two other poems of that period – "The Sail" and "The Hussar" – were later rated among his best.[4][5]

In 1832 Lermontov tried his hand at prose for the first time. The unfinished novel Vadim, telling the story of the 1773–1775 Yemelyan Pugachev-led peasant uprising, was stylistically flawed and short on ideas. Yet, free of Romantic pathos and featuring well-crafted characters as well as scenes from peasant life, it marked an important turn for the author now evidently intrigued more by history and folklore than by his own dreams.[15]

Two branches of Lermontov's early 1830s poetry – one dealing with the Russian Middle Age history, another with the Caucasus – couldn't differ more. The former were stern and stark, featured a dark, reserved hero ("The Last Son of Freedom"), its straightforward storyline developing fast. The latter, rich with ethnographical side issues and lavish in colourful imagery, boasted flamboyant characters ("Ismail-Bey", 1832).[4]

Even as a Moscow University's boarding school student Lermontov was a socially aware young man. His "The Turk's Lament" (1829) expressed strong anti-establishment feelings ("This place, where a man suffers from slavery and chains; my friend, this is my fatherland"), the "July 15, 1830" poem greeted the July Revolution, while "The Last Son of Freedom" was a paean to (obviously, idealized) Novgorod Republic. But Lermontov, a fiery tribune, has never become a political poet. Full of inner turmoil and anger, his protagonists were riotous but never rational or promoting any particular ideology.[31]

The Cadet School seemed to have stymied in Lermontov all interests except one, for wanton debauchery. His pornographic (and occasionally sadistic) Cavalry Junkers' poems which circulated in manuscripts, marred his subsequent reputation so much so that admission of familiarity with Lermontov's poetry was not permissible for any young upper-class woman for a good part of the 19th century. "Lermontov churned out for his pals whole poems in improvisational manner, dealing with things which were apparently part of their barrack and camp lifestyle. Those poems, which I've never read, for they weren't intended for women, bear all the mark of the author's brilliant, fiery temperament, as people who've read them attest", Yevdokiya Rostopchina admitted.[32] These poems were published only once, in 1936, as part of a scholarly edition of Lermontov's complete works, edited by Irakly Andronikov.

This lean period bore a few fruits: "Khadji-Abrek" (1835), his first ever published poem, and 1836's Sashka (a "darling son of Don Juan", according to Mirsky), a sparkling concoction of Romanticism, realism and what might be termed a cadet-style verse. The latter remained unfinished, as did Princess Ligovskaya (1836), a society tale which was influenced at least to some extent by Gogol's Petersburg Stories and featured characters and dilemmas not far removed from those that would form the base of A Hero of Our Time.[15][19]

Arrested, jailed and sent to the Caucasus in 1837, Lermontov dropped "Princess Ligovskaya" and never got back to it. Much more important to him was The Masquerade; written in 1835, it got re-worked several times – the author tried desperately to publish it. Close to French melodrama and influenced by Victor Hugo and Alexander Dumas (but also owing a lot to Shakespeare, Griboyedov and Pushkin), Masquerade featured another hero whose want was to 'throw a gauntlet' to the unsympathetic society and then get tired of his own conflicting nature, but was interesting mostly for its realistic sketches of the high society life, which Lermontov was getting more and more critical of.[15]

Lermontov's fascination with Byron has never waned. "Having made the English pessimism a brand of his own, he's imparted it a strong national favour to produce the very special Russian spleen, which has been there always in the Russian soul... Devoid of cold skepticism or icy irony, Lermontov's poetry is full instead of typically Russian contempt for life and material values. This mix of deep melancholy on the one hand and wild urge for freedom on the other, could be found only in Russian folk songs," biographer Skabichevsky wrote.[31]

In 1836–1838 Lermontov's interest in history and folklore re-awakened. Eclectic Boyarin Orsha (1836), featuring a pair of conflicting heroes, driven one by blind passions, another by obligations and laws of honour, married the Byronic tradition with the elements of historical drama and folk epos. An ambitious folk epic, The Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov (initially banned, then published in 1837 due to Vasily Zhukovsky's efforts), was unique for its unexpected authenticity. Lermontov, who haven't got a single academic source to rely upon, "entered the realm of folklore as a real master and totally merged with its spirit," according to Belinsky.[5] Lermontov's Cossack Lullaby "went the whole round: from the original folklore source to literature, and from literature to living folklore. ... For one and a half centuries people have performed these literary lullabies in real lulling situations [in Russia]," according to Valentin Golovin.[33]

"Death of the Poet" (1837), arguably the strongest political declaration of its time (its last two lines, "and all of your black blood won't be enough to expiate the poet's pure blood", construed by some as a direct call for violence), made Lermontov not just famous, but almost worshipped, as a "true heir to Pushkin". More introspective but no less subversive was his "The Thought" (1838), an answer to Kondraty Ryleyev's "The Citizen" (1824), damning the lost generation of "servile slaves".[5]

Otherwise, Lermontov's short poems range from indignantly patriotic pieces like "Fatherland" to the pantheistic glorification of living nature (e.g., "Alone I set out on the road ...") Some saw Lermontov's early verse as puerile, since, despite his dexterous command of the language, it usually appeals more to adolescents than to adults. Later poems, like "The Poet" (1838), "Don't Believe Yourself" (1839) and "So Dull, So Sad..." (1840) expressed skepticism as to the meaning of poetry and life itself. On the other hand, for Lermontov the late 1830s was a period of transition; drawn more to Russian forests and fields rather than Caucasian ranges, he achieved moments of transcendental solemnity and clear vision of heaven and Earth merged into one in poems like "The Branch of Palestine", "The Prayer" and "When yellowish fields get ruffled..."[5]

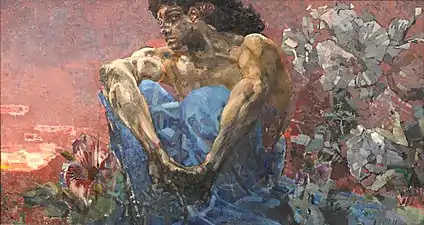

Both his patriotic and pantheistic poems had an enormous influence on later Russian literature. Boris Pasternak, for instance, dedicated his 1917 poetic collection of signal importance to the memory of Lermontov's Demon. This long poem (started as early as 1829 and finished some ten years after) told the story of a fallen angel admitting defeat in the moment of his victory over Tamara, a Georgian "maid of mountains". Having read by censors as the celebration of carnal passions of the "eternal spirit of atheism", it remained banned for years (and was published for the first time in 1856 in Berlin), turning arguably the most popular unpublished Russian poem of the mid-19th century. Even Mirsky, who ridiculed Demon as "the least convincing Satan in the history of the world poetry," called him "an operatic character" and fitting perfectly into the concept of Anton Rubinstein's lush opera (also banned by censors who deemed it sacrilegious) had to admit the poem had magic enough to inspire Mikhail Vrubel for his series of unforgettable images.[5]

Another 1839 poem investigating the deeper reasons for the author's metaphysical discontent with society and himself was The Novice, or Mtsyri (in Georgian), the harrowing story of a dying young monk who'd preferred dangerous freedom to protected servitude. The Demon defiantly lives on, Mtsyri dies meekly, but both epitomize the riotous human spirit's stand against the world that imprisons it. Both poems are beautifully stylized and written in fine, mellifluous verse which Belinsky found "intoxicating".[15]

By the late 1830s Lermontov became so disgusted with his own early infatuation with Romanticism as to ridicule it in Tambov Treasurer's Wife (1838), a close relative to Pushkin's Count Nulin, performed in stomping Yevgeny Onegin rhyme. Even so, it is his 1812 War historical epic Borodino (1837), a 25th Anniversary hymn to the victorious Russian spirit, related in simple language a tired war veteran, and Valerik (defined by Mirsky as a missing link between the "Copper Rider" and the War and Peace battle scenes) that are seen by critics as the two peaks of Lermontov's realism. This newly found clarity of vision allowed him to handle a Romantic theme with Pushkin's laconic precision most impressively in "The Fugitive".[15] Tellingly, while Pushkin (whose poem "Tazit"'s plotline was here used) saw the European influence as a healthy alternative to the patriarchal ways of Caucasian natives, Lermontov tended to idealize the local communities' centuries-proven customs, their morality codex and the will to fight for freedom and independence to the bitter end.[34]

Lermontov had a peculiar method of circulating ideas, images and even passages, trying them again and again through the years in different settings until each would find itself a proper place – as if he could "see" in his imagination his future works but was "receiving" them in small fragments. Even "In Memory of A.I. Odoyevsky" (1839) the central episode is, in effect, the slightly re-worked passage borrowed from Sashka.[4]

A Hero of Our Time (1840), a set of five loosely linked stories unfolding the drama of the two conflicting characters, Pechorin and Grushnitsky, who move side by side towards a tragic finale as if driven by destiny itself, proved to be Lermontov's magnum opus. Vissarion Belinsky praised it as a masterpiece, but Vladimir Nabokov (who translated the novel into English) was not so sure about the language: "The English reader should be aware that Lermontov's prose style in Russian is inelegant, it is dry and drab; it is the tool of an energetic, incredibly gifted, bitterly honest, but definitely inexperienced young man. His Russian is, at times, almost as crude as Stendhal's in French; his similes and metaphors are utterly commonplace, his hackneyed epithets are only redeemed by occasionally being incorrectly used. Repetition of words in descriptive sentences irritates the purist," he wrote.[19] D.S. Mirsky thought differently. "The perfection of Lermontov's style and narrative manner can be appreciated only by those who really know Russian, who feel fine imponderable shades of words and know what has been left out as well as what has been put in. Lermontov's prose is the best Russian prose ever written, if we judge by the standards of perfection and not by those of wealth. It is transparent, for it is absolutely adequate to the context and neither overlaps it nor is overlapped by it," he maintained.

In Russia A Hero of Our Time seems to have never lost its relevance: the title itself became a token phrase explaining dilemmas haunting this country's intelligentsia. And Lermontov's reputation as an 'heir to Pushkin' there is seldom doubted. His foreign biographers, though, tend to see a more complicated and controversial picture. According to Lewis Bagby, "He led such a wild, romantic life, fulfilled so many of the Byronic features (individualism, isolation from high society, social critic and misfit), and lived and died so furiously, that it is difficult not to confuse these manifestations of identity with his authentic self. …Who Lermontov had become, or who he was becoming, is unclear. Lermontov, like many a romantic hero, once closely examined, remains as open and unfinished as his persona seems closed and fixed."[19]

Legacy

The town of Lermontov, Russia (granted municipal status in 1956), the cruise liner MS Mikhail Lermontov (launched in 1970) and the minor planet 2222 Lermontov (discovered in 1977)[35] were named after him.

The crew of Soyuz TMA-21 selected Tarkhany as their call sign, after the estate where Lermontov spent his childhood and where his remains are preserved.[36]

On 3 October 2014, a monument to Lermontov was unveiled in the Scottish village of Earlston, the place being selected due to a suggested association of Lermontov's descent with Thomas the Rhymer.[37] Until only a few years earlier, the connection had been little-known in Scotland.[38]

Lermontov has been depicted in numerous movies and TV series. In 2012 Azerbaijani movie "Ambassador of Morning", telling the story of another great poet, Abbasgulu Bakikhanov, Mikhail Lermontov was depicted by Oleg Amirbekov.[39] In 2014, in memory of his 200th birthday, a biography documentary about him was released in Russia.[40][41]

Selected bibliography

Prose

- Vadim (1832, unfinished; published in 1873)

- Princess Ligovskaya (Knyaginya Ligovskaya, 1836, unfinished novel first published in 1882)

- "Ashik-Kerib" (the Azerbaijani fairytale, 1837, first published in 1846)

- A Hero of Our Time (Герой нашего времени, 1840; 1842, 2nd edition; 1843, 3rd edition), novel

Dramas

- The Spaniards (Ispantsy, tragedy, 1830, published 1880)

- Menschen und Leidenschaften (1830, published 1880)

- A Strange Man (Stranny tchelovek, 1831, drama/play published 1860)

- Masquerade (1835, first published in 1842)

- Two Brothers (Dva brata, 1836, published in 1880)

- Arbenin (1836, the alternative version of Masquerade, published in 1875)

Poems

- The Circassians (Tcherkesy, 1828, published in 1860)

- The Corsair (1828, published in 1859)

- The Culprit (Prestupnik, 1828, published in 1859)

- Oleg (1829, published in 1859)

- Julio (1830, published in 1860)

- Kally ("The Bloody One", in Circassian, 1830, published in 1860)

- The Last Son of Freedom (Posledny syn volnosti, 1831–1832, published in 1910)

- Azrail (1831, published in 1876)

- Confession (Ispoved, 1831, published in 1889)

- Angel of Death (Angel smerti, 1831; published in 1857 – in Germany; in 1860 – in Russia)

- No, I'm not Byron (published in 1832)

- The Sailor (Moryak, 1832, published in 1913)

- Ismail-Bei[42] (1832, published in 1842)

- A Lithuanian Woman (Litvinka, 1832, published in 1860)

- Aul Bastundji (1834, published in 1860)

- The Junkers Poems ("Ulansha", "The Hospital", "Celebration in Petergof", 1832–1834, first published in 1936)

- Khadji-Abrek (1835, Biblioteka Dlya Chtenya)

- Mongo (1836, published in 1861)

- Boyarin Orsha (1836, published in 1842)

- Sashka (1835–1836, unfinished, published in 1882)

- The Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov (Pesnya kuptsa Kalashnikova, 1837)

- Borodino (1837)

- The Death of the Poet (1837)

- Tambov Treasurer's Wife (Tambovskaya Kaznatcheysha, 1838)

- The Cossack Lullaby (1838)

- The Fugitive (Beglets, circa 1838, published in 1846)

- Demon (1838, published in 1856 in Berlin)

- The Novice (Mtsyri, in Georgian, 1839, published in 1840)

- Valerik (1840)

- The Children's Fairytale (Detskaya skazka, 1839, unfinished, published in 1842)

Selected short poems

- The Turk's Laments (Zhaloby turka, 1829)

- Two Brothers (1829, Dva brata, published in 1859)

- Napoleon (1830)

- The Spring (Vesna, 1830)

- 15 July 1830 (1830)

- The Terrible Fate of Father and Son... (Uzhasnaya sudba otsa i syna... 1831)

- The Reed (Trostnik, 1831)

- Mermaid (Rusalka, 1831)

- The Wish (Zhelanye, 1831)

- The Angel (Angel, 1831)

- The Prophecy (Predskazaniye, 1831)

- The Sail (Parus, 1831)

- Forgive Me, Will We Meet Again?.. (Prosti, uvidimsya li snova..., 1832)

- The Hussar (Gusar, 1832)

- Death of the Poet (1837)

- The Branch of Palestine (Vetka Palestiny, 1837)

- Mother Of God, Here I Stand (Molitva, 1837)

- Farewell, Unwashed Russia (Proshchai, nemytaya Rossiya, 1837)

- When Yellowish Fields Get Ruffled... (Kogda volnuyetsa zhelteyushchaya niva..., 1837)

- The Thought (Duma, 1838)

- The Dagger (Kinzhal, 1838)

- The Poet (1838)

- Don't Believe Yourself... (Ne ver sebye..., 1839)

- Three Palms (Tri palhmy, 1839)

- In the Memory of A.I.Odoyevsky (1839)

- So Dull, So Sad... (I skuchno, i grustno..., 1840)

- How Often, Surrounded by a Motley Crowd... (Kak tchasto, okruzhonny pyostroyu tolpoyu..., 1840)

- Little Clouds (Tuchki, 1840)

- The Journalist, the Reader and the Writer (1840)

- The Heavenly Ship (Vozdushny korabl, 1840)

- Fatherland (Rodina, 1841)

- The Princess of the Tide, 1841, ballad

- The Dispute (Spor, 1841)

- Alone I set out on the road... (Vykhozu odin ya na dorogu..., 1841)

See also

- Un cœur en hiver – film by Claude Sautet based on one of the episodes in "A Hero of Our Time"

- Ashik Kerib – a 1988 film directed by Sergei Parajanov, based on a short story by Lermontov

- Hero of Our Time (film), 1966 Soviet drama film directed by Stanislav Rostotsky

- A Hero of Our Time – English translation by Irwin Paul Foote, Penguin Classics

- Lermontov (crater) – crater on the planet Mercury named after him

- M. Yu. Lermontov (ship), 1958 cruise ship

- Mikhail Lermontov, ocean liner built in 1972

References

- ↑ "Lermontov". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- 1 2 3 4 Powelstock 2011, p. 27.

- ↑ Babulin, I.B. The New Lines Regiments in the Smolensk War, 1632–1634 Reitar, No. 22, 2005

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mirsky, D. (1926). "Lermontov, Mikhail Yurievich". az.lib.ru. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 "Lermontov, Mikhail Yurievich". Russian Authors. Biobibliographical Dictionary. Vol 1. Prosveshchenye Publishers, Moscow. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- 1 2 Skabichevsky, Alexander. "M. Yu. Lermontov. His Life and Works". Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Manuylov, V.A. The Life of Lermontov. Timeline. Works by M.Y. Lermontov in 4 volumes. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura Publishers. Moscow, 1959. Vol. IV. pp. 557–588

- ↑ Viskovatov, P.A. (1891). "The Life and Works of M.Y. Lermontov. Chapter 1". ruslit.com.ua. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ↑ Friedlender, G.M., Lyubovich, N.A. Commentaries to Menschen und Liedenschaften (1930). Works by M.Y. Lermontov in 4 volumes. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura Publishers. Moscow, 1959. Vol. III. p. 489

- ↑ Viskovatov, P.A. Chapter 2. Archived 24 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine (p. 5)

- ↑ Viskovatov, P.A. Chapter 2 Archived 24 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine p. 6

- ↑ Viskovatov, P.A. Chapter 1 Archived 24 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, p. 4

- ↑ Skabichevsky, Alexander. Chapter 3.

- 1 2 3 Skabichevsky, Alexander Chapter 2

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Sirotkina, Yelena (2002). "Biography. The Works by M.Y. Lermontov in 10 volumes. Moscow, Voskresenye Publishers". www.krugosvet.ru // Voskresenye Publishers. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ Powelstock 2011, p. 28.

- 1 2 Skabichevsky, Alexander. Chapter IV

- ↑ Viskovatov, P.A. Viskovatov, Ch. V Archived 24 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Lewis Bagby (2002). A Hero of Our Time. Introduction. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 9780810116801. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ Skabichevsky, Alexander Chapter V.

- 1 2 3 Skabichevsky, Alexander. Chapter 6.

- 1 2 Skabichevsky, Alexander. Chapter 7.

- 1 2 Skabichevsky, Alexander. Chapter 8.

- ↑ The Preface by Irakly Andronikov in A Hero of Our Time (1985), Raduga Publishers, Moscow. ISBN 5-05-000016-5

- ↑ Skabichevsky, Alexander. Chapter 9.

- ↑ Skabichevsky, Alexander. Chapter 10.

- 1 2 Skabichevsky, Alexander. Chapter 11.

- 1 2 Skabichevsky, Alexander. Chapter 12.

- ↑ Skabichevsky, Alexander. Chapter 13.

- ↑ Works by M.Y. Lermontov in 4 volumes. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura Publishers. Moscow, 1959. Vol. IV, pp. 390–391

- 1 2 Skabichevsky, Alexander. "M.Yu. Lermontov. His Life and Works. Chapter 14". Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ↑ "Goshpital (Гошпиталь)". Russian Poetry, XIX–XX. The Online Library. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ↑ Golovin, Valentin. The Russian lullaby in folklore and literature. Summary.

- ↑ The Works of M.Y. Lermontov in 4 Volumes. Commentaries by E.E. Naidich, A.N. Mikhaylova, L.N. Nazarova. Commentaries to Lermontov's poems. Vol. II, p. 491

- ↑ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 181. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

- ↑ Kudriavtsev Anatoli (4 April 2011). "Gagarin spaceship ready for launch". The Voice of Russia. Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ↑ Johnston, Willie (3 October 2014). "Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov celebrated in Scotland". BBC News. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ↑ "Russian Poet Is Celebrated in Scotland, a Land He Never Saw A Russian Poet is Celebrated in Scotland, a Land He Never Saw". New York Times. 27 September 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ↑ "Лермонтов, Михаил Юрьевич, музыкальный театр, образ лермонтова, в игровом кино, документальные фильмы". www.cultin.ru.

- ↑ "Фильм Лермонтов (2014): фото, видео - Вокруг ТВ". Вокруг ТВ.

- ↑ "«Ещe минута, и я упал...» Документальный фильм к 200-летию М. Ю. Лермонтова" – via www.1tv.ru.

- ↑ https://mihail-lermontov.su/poemy/izmail-bej/?lang=en

Sources

- Powelstock, David (2011). Becoming Mikhail Lermontov: The Ironies of Romantic Individualism in Nicholas I's Russia. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0810127883.

- Shedden-Ralston, William Ralston (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 484–485.

Further reading

- Kelly, Laurence (2003). Lermontov: Tragedy in the Caucasus. Tauris Parke. ISBN 978-1-86064-887-8.

External links

- Short biography with links to other Lermontov material

- Short biography

- Short biography

- Works by Mikhail Lermontov at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Mikhail Lermontov at Internet Archive

- Works by Mikhail Lermontov at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Translations of various poems by Mikhail Lermontov

- Translation of "Borodino"

- Translation of "The Prophecy"

- Translation of "The Sail"

- Translation of "A Sail"

- Translation of "The Sail"

- Translation of "Farewell! – unwashed, indigent Russia"

- Translation of "The Prisoner"

- Translation of "The Dream"

- Translation of "Cossack Lullaby"

- Translation of "We parted..."

- Translation of "Because"

- State Lermontov Museum and Reserve at Tarkhany

Dual-language links

- Mikhail Lermontov poetry on YouTube. 1986 Mosfilm movie

- Various Lermontov poems in Russian with English translations, some audio files

- Various Lermontov poems, many in Russian, some English translations, at Friends & Partners

- Russian text of various poems with English translations

- Russian text of «Смерть поэта» ("Death of the Poet") with English translation

- Russian text of "Cossack Lullaby" with English translation

Russian-language links

- Online Lermontov shrine

- Short biography at Russian Biographical Dictionary

- Short biography at Megabook

- Texts of various Lermontov works

- Lermontov Museum, Moscow

- Photographs of State Lermontov Museum and Reserve at Tarkhany

- The ancestors of Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov

- "I Walk Out Alone Upon My Way" performed by Anna German

- Mikhail Lermontov poetry