The military budget of Japan is the portion of the overall budget of Japan that is allocated for the funding of the Japanese Self-Defence Forces. This military budget finances employee salaries and training costs, the maintenance of equipment and facilities, support of new or ongoing operations, and the development and procurement of new weapons, equipment, and vehicles.

In December 2020, Suga's government approved a record 5.34 trillion yen ($51.7 billion/€42.4 billion) defence budget for the fiscal year 2021. This includes investment in the development of stealth fighter jets, new long-range missile systems and new compact warships, with the goal to counter potential threats from China and North Korea. With the move, the government continues to increase in defence spending year on year, as was the case under the Shinzo Abe government in the eight preceding years.[1]

History

Cold War

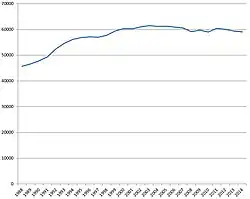

Even during the Cold War arms race of the 1980s, the Defence budget was accorded a relatively low priority in Japan. According to Japanese security policy, maintaining a military establishment is only one method—and by no means the best method—to achieve national security. Diplomacy, economic aid and development, and a close relationship with the United States under the terms of the 1960 security treaty are all considered more important. For FY 1986 through FY 1990, defence's share of the general budget was around 6.5%, compared with approximately 28% for the United States. In 1987 Japan ranked sixth in the world in total defence expenditures behind the Soviet Union, the United States, France, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), and Britain. By 1989 it ranked third after the United States and the Soviet Union, mainly because of the increased value of the yen. In FY 1991, defence accounted for 6.2% of the budget. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Japan was ranked fourth in world in 2004-2005, spending $42.1 billion; according to The World Factbook, CIA, Japan was fifth, spending $44.7 billion (the ranking is different because of the CIA's radically higher estimate of spending by the People's Republic of China).[2]

In addition to annual budgets, the Defense Agency prepared a series of cabinet-approved buildup plans beginning in 1957, which set goals for specific task capabilities and established procurement targets to achieve them. Under the first three plans (for 1958-60, 1962–66, and 1967–71), funding priorities were set to establish the ability to counter limited aggression. Economic difficulties following the 1973 oil crisis, however, caused major problems in achieving the Fourth Defence Buildup Plan (1972–76), and forced funding to be cut, raising questions about the basic concepts underlying defence policies.

In 1976 the government recognized that substantial increases in spending, personnel, and bases would be virtually impossible. Instead, a "standard defence concept" was suggested, one stressing qualitative improvements in the Self-Defence Forces, rather than quantitative ones. It was decided that defence spending would focus on achieving a basic level of defence as set forth in the 1976 National Defence Program Outline. Thereafter, the government ceased to offer buildup plans that alarmed the public by their seemingly open-ended nature and switched to reliance on single fiscal year formulas that offered explicit, attainable goals.

Defence spending increased slightly during the late 1970s, and in the 1980s only the defence and Official Development Assistance budgets were allowed to increase in real terms. In 1985 the Defence Agency developed the Mid-Term Defence Estimate objectives for FY 1986 through FY 1990, to improve SDF front-line equipment and upgrade logistic support systems. For the GSDF, these measures included the purchase of advanced weapons and equipment to improve antitank, artillery, ground-to-sea firepower, and mobile capabilities. For the MSDF, the focus was on upgrading antisubmarine capabilities, with the purchase of new destroyer escorts equipped with the Aegis system and SH-60J antisubmarine helicopters, and on improving antimine warfare and air defence systems. ASDF funds were concentrated on the purchase of fighter aircraft and rescue helicopters. The entire cost of the Mid-Term Defence Estimate for FY 1986 through FY 1990 was projected at approximately ¥18.4 trillion (approximately US$83.2 billion, at the 1985 exchange rate).

In FY 1989, the ¥3.9 trillion defence budget accounted for 6.49% of the total budget, or 1.006% of GNP. In addition to the Defence Agency itself, the defence budget supported the Defence Facilities Administration Agency and the Security Council. Defence Agency funding covered the GSDF, the MSDF, the ASDF, the internal bureaus, the Joint Staff Council, the National Defence Academy, the National Defence Medical College, the National Institute for Defence Studies, the Technical Research and Development Institute, and the Central Procurement Office.

The FY 1990 defence budget, at 0.997% of the forecast GNP, dipped below the 1% level for the first time since it was reached in 1987. But the more than ¥4.1 trillion budget still marked a 6.1% increase over the FY 1989 defence budget and provided virtually all of the ¥104 billion requested for research and development, including substantial funds for guided-missile and communications technologies. Although some ¥34.6 billion was authorized over several years for joint Japan-United States research and development of the experimental FSX fighter aircraft, disputes over this project were believed to have convinced the Defence Agency to strengthen the capability of the domestic arms industry and increase its share of SDF contracts. After originally being cut, funds were also restored for thirty advanced model tanks and the last Aegis multiple-targeting-equipped destroyer escort needed to complete the Mid-Term Defence Estimate. The 6.1% defence increase was accompanied by an even larger (8.2%) increase in Official Development Assistance funding. The defence budget continued to grow in real terms in the early 1990s to ¥4.38 trillion in 1991 and ¥4.55 trillion in 1992 but remained less than 1% of GNP.

Japanese officials resist United States pressure to agree formally that Japan will support more of the cost of maintaining United States troops, claiming that such a move will require revision of agreements between the two nations. But in FY 1989, the Japanese government contributed US$2.4 billion—roughly 40%—of the total cost. The contribution slated for FY 1990 was increased to US$2.8 billion—nearly 10% of the total defence budget—and by the end of FY 1990 the Japanese government expected to assume all expenses for utilities and building maintenance costs for United States troops stationed in Japan.

After the Cold War

According to the Ministry of Defence of Japan, the 2008 defence budget was ¥4.74 trillion, down by 0.8% from the ¥4.78 trillion recorded in 2007.[3] This slight decline came despite attempts by the governing LDP to enhance the status of national defence by upgrading the Defence Agency to the Ministry of Defence, effective January 9, 2007.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ "Japan's Cabinet approves record defense budget | DW | 21.12.2020". Deutsche Welle.

- ↑ "CIA - the World Factbook -- Rank Order -". Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

- ↑ Japan Ministry of Defence home page, English-language version

- ↑ "About Ministry | Japan Ministry of Defense". 1 September 2019. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division.