| Operator | Rosaviakosmos |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 1995-047A |

| SATCAT no. | 23665 |

| Mission duration | 179 days, 1 hour, 41 minutes, 45 seconds |

| Orbits completed | 2833 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Soyuz 7K-STM no. 71 |

| Spacecraft type | Soyuz-TM |

| Manufacturer | RKK Energia |

| Launch mass | 7,150 kilograms (15,760 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 3 |

| Members | Yuri Gidzenko Sergei Avdeyev Thomas Reiter |

| Callsign | Ура́н (Uran) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | September 3, 1995, 09:00:23 UTC |

| Rocket | Soyuz-U2 |

| Launch site | Baikonur Launch Pad 1 |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | February 29, 1996, 10:42:08 UTC |

| Landing site | 51°23′N 67°27′E / 51.38°N 67.45°E |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Perigee altitude | 339 kilometres (211 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 340 kilometres (210 mi) |

| Inclination | 51.6 degrees |

| Docking with Mir | |

| Docking port | Forward |

| Docking date | 5 September 1995, 10:29:53 UTC |

| Undocking date | 29 February 1996, 7:20:06 UTC |

| Time docked | 176.8 days |

Soyuz programme (Crewed missions) | |

Soyuz TM-22 was a Soyuz spaceflight to the Soviet space station Mir.[1] It launched from Baikonur Cosmodrome Launch Pad 1 on September 3, 1995.[1] After two days of free flight, the crew docked with Mir to become Mir Principal Expedition 20 and Euromir 95.[2] Mir 20 was a harbinger of the multinational missions that would be typical of the International Space Station.[2] After 179 days, 1 hour and 42 minutes on orbit, Reiter obtained the record for spaceflight duration by a Western European.[3]

Crew

| Position | Crew | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | First spaceflight | |

| Flight Engineer | Second spaceflight | |

| Flight Engineer | First spaceflight | |

Mission highlights

Soyuz TM-22 was a Russian transport spacecraft that transported cosmonauts to the Mir space station for a 179-day stay. It was launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome and docked on September 5, 1995, with Mir's Kvant-2 module at the port that was vacated by Progress M-28 a day before.

Soyuz TM-22 was the final mission launched on the Soyuz-U2 launch vehicle, fueled by synthetic Syntin rather than the RP-1 fuel used in other variants of the Soyuz launch vehicle.

The crew's commander was Yuri Pavlovich Gidzenko of the Russian Air Force.[4] The flight engineer was Sergey Vasilyevich Avdeyev of RKK Energiya.[4] Thomas Reiter was the first ESA cosmonaut on a long duration Mir crew[5] as part of the European Mission "Euromir 95".[1]

While docked with Mir, the Soyuz was joined by Progress M-29, Space Shuttle Atlantis as part of STS-74 and Progress M-30.[1]

The spaceflight took two months longer than planned due to lack of funds for Soyuz TM-23.[1]

Mir principal expedition 20 and Euromir 95

Mir 20 was the second Mir mission with the Euromir designation and an ESA cosmonaut as part of the crew. The first was Ulf Merbold with Euromir94.[2] The objectives of Euromir95 was to study the effects of microgravity on the human body, develop materials for the space environment, to capture particles of cosmic and anthropogenic dust in low Earth orbit and to test new space equipment.[2] Mir 20 was the second mission to include a NASA Space Shuttle docking.[2] During that phase of the mission, Mir housed crews from four countries: Russia, Canada, Germany and the United States.[2]

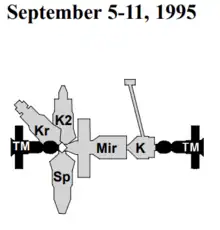

September 5–11, 1995

Soyuz-TM 22 Docks

After two days of autonomous orbital flight, on September 5, the spacecraft docked with Mir after circling from 90-120m out at the -X docking port.[2] After an hour and a half, the crew checked the hatch seals, removed their space suits and entered the station and were welcomed by Anatoly Solovyev and Nikolai Budarin of Mir Principle Expedition 19 with the traditional bread and salt.[2] The crews then began a week of joint work that included a handover from the Mir 19 crew to familiarize Mir 20 with the status of the onboard systems and experiments.[2]

September 11 - October 10, 1995

Mir 19 Ends

Solovyev and Budarin ended their 75-day mission by departing on the Soyuz-TM 21 on September 11.[2] Their Soyuz landed safely in Kazakhstan, 302 km northeast of Arkalyk, far away from the aiming point, however the rescue crews found Mir 19 in excellent condition.[2]

Euromir Science Activities Begin

The Mir 20 crew began activating and calibrating the Euromir 95 experiments on September 13. The 41 experiments included 18 life sciences, 5 astrophysics, 8 material science and 10 technology experiments.[2] An average of four and a half hours per day was allotted for experimental work, the rest of the time was devoted to exercise and station maintenance.[2] Thomas Reiter, in addition to his Euromir duties, participated in Russian experiments and in his role as flight engineer, he helped maintain the station's onboard equipment.[2]

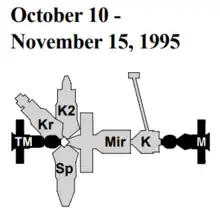

October 10 - November 15, 1995

Progress-M 29 arrives

Progress-M 29 was launched from the Baiknour Cosmodrome on October 8, 1995, at 18:51 UTC on a Soyuz-U rocket.[2] The resupply ship docked with Mir on October 10, 1995, at 20:23 UTC with about 2.5 tons of fresh supplies and equipment for the Mir 20 crew including 80 kg of experimental hardware for Euromir 95.[2]

Mir 20/Euromir 95 extended

On October 6, 1995, the decision was made to extend the Mir 20 mission by 44 days at a meeting of the RSA, ESA, RSC Energia, the Russian Central Specialized Design Bureau (Soyuz rocket designer) and representatives of the Progress Plant where the Soyuz-U rocket for the launch of Mir 21 was under construction. By postponing the Soyuz TM-23 launch from January 15, 1996, to February 21, 1996, they were able to shift much of the expenditure for the vehicle processing to the next fiscal year, relieving strain on the RSA budget.[2] This also allowed full usage of the Soyuz-TM 22 module's 180-day lifetime, allow time for more Euromir research and an extra EVA.[2]

First Mir 20/Euromir 95 EVA

Thomas Reiter became the first ESA cosmonaut to perform an EVA when he climbed through the Kvant 2 hatch on October 20 with Sergei Avdeyev. In a successful 5 hour and 11 minute EVA, they installed four elements on the ESEF: two exposure cassettes, a spacecraft environmental monitoring package and a control electronics box on the forward section of the Spektr module.[2] One of the cassettes would be opened remotely from within the station to sample the Draconids meteor stream when the Earth passed through the tail of the Giacobini Zinner comet.[2]

Coolant loop leak discovered and repaired

On November 1, a coolant line to the core module air regeneration system was found to be leaking. Approximately 1.8L of an ethylene glycol mixture had leaked inside the Mir module. Shutting down the coolant loop required shutting down the primary carbon dioxide removal system in Kvant and the oxygen replenishment system.[2] While they were off, the backup air scrubber using lithium hydroxide canisters similar to those used on the Space Shuttle was used to scrub the carbon dioxide. The leak was found a few days later and repaired with a putty-like substance.[2]

Dutch Biokin Air Scrubber tested

Two Dutch companies sponsored by the ESA and the Dutch National Institute for Aerospace Programs developed a 500g system to use microbes to filter air by converting airborne contaminants into harmless compounds.[2] The system was activated by the crew on November 9, run for a week and then put in a small freezer for return to Earth on STS-74.[2]

Shuttle Docking Module connection

The Docking Module was designed and built in 1994 and 1995 in Russia by RSC Energia for the RSA. The 4090 kg, 4.7m long, 2.2m diameter module was delivered to Kennedy Space Center on June 7, 1995, so that the Space Shuttle Atlantis could bring it to Mir on STS-74.[2] The module simplified the Space Shuttle orbiter dockings with Mir by eliminating the need to move Kristall to the -X port on Mir each time the Space Shuttle visited. The length also provided more clearance between the orbiter and the Mir solar arrays.[2] The module had identical Androgeynous Peripheral Assembly Systems (APASs) on each end. APAS-1 attached to Kristall, APAS-2 attached to the Shuttle ODS. Visiting crews would then enter the pressurized interior through the APAS-2 hatch and then access Kristall through the APAS-2 hatch.[2]

Atlantis launched from Kennedy Space Center on November 12 at 7:30 am EST on the STS-74 mission.[2] For the first two days of the flight, Kenneth Cameron, Atlantis Commander and James Halsell, Atlantis Pilot executed a series of reaction control jet firings to gradually bring Atlantis closer to Mir. On the third day, Chris Hadfield and William McArthur grappled the Docking Module with the 50-foot mechanical arm, lifting it horizontally out of the bay. When it was clear, he pivoted the module 90 degrees to a vertical position and spun it almost 180 degrees and brought it close to Kristal.[2] Once Hadfield placed the arm in a 'limp' position (no power, no mechanical parts working), Cameron fired Atlantis's steering thrusters to gently bring the docking systems together, docking the module with Kristal. The next day, the Space Shuttle Atlantis used the docking module's top hatch to dock with Mir.[2]

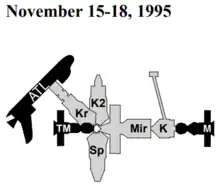

November 15–18, 1995

Second Shuttle-Mir docking

On November 15, the fourth day of the STS-74 mission, after a 'go' from Russian and U.S. ground controllers, Cameron slowed the orbiters approach to less than one inch per second and successfully docked with the station at 6:28 UTC about 216 nautical miles above western Mongolia.[2] After two and a half hours of verification and seal checkouts, Cameron opened the Docking Module hatch and met Mir 20 Commander Gidzenko with a handshake that signaled the formation of a multinational crew.[2]

Multinational crew activities

The crews transferred cargo items between the visiting Orbiter and Mir over the three days the two were docked. From the Orbiter, Mir received 300 pounds of food, 700 pounds of experimental equipment, 900 pounds of by-product water from Atlantis' fuel cells and 20 lithium hydroxide canisters to serve as backup for Mir's primary carbon dioxide removal system. From Mir, the Orbiter received 800 pounds of research samples collected during Euromir 95 and experimental equipment no longer needed by the station.[2]

The crews also spoke with the press and received congratulations from Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin, Canadian Industry Minister John Manley, NASA Administrator Daniel Goldin and U.N. Secretary General Boutrous Boutrous-Ghali.[2]

While the Shuttle was docked with Mir, the crews cooperated in medical experiment sand environmental investigations designed as part of International Space Station Phase I research.[2] The Photogrammetric Appendage Structural Dynamics Experiment (PASDE) was a set of three photogrammetric instruments located in the Orbiter payload bay and recorded Mir solar array dynamics during the docking and docked phase of the mission.[2] The International Space Station Risk Mitigation Experiments evaluated the acoustics of the environment aboard Mir, the alignment stability of the Atlantis-Mir docked configuration and the remote communication systems.[2] A series of jet firings by both Mir and Atlantis evaluated the dynamics of the complicated structure, which at more than 500,000 pounds, set a new record for a conjoined orbital mass.[2]

Atlantis undocking

Atlantis undocked with the station early in the morning of November 18.[2] Once the Orbiter was 525 feet out, he began a fly around, taking a photographic survey of the station. Four and half hours after undocking, Cameron lowered Atlantis to another orbit.[2] Two days later, on November 20 at 12:02 EST, the Orbiter Atlantis landed at Kennedy Space Center in Floriday, ending a 128 orbit mission after 8 days, 4 hours and 31 minutes.[2]

November 18 - December 19, 1995

Euromir experiments resume

After the Space Shuttle departure, the Mir 20/Euromir 95 crew continued with their medical tests and material processing experiments. In addition to equipment brought on board for Euromir, Reiter used the Austrian Optovert equipment that had been on Mir since the Austro-Mir mission in October 1991.[2] He investigated the effects of weightlessness on human motor system performance and the interactions of the vestibular system and visual organs.[2]

Gyrodyne maintenance and second Mir 20 EVA

The cosmonauts performed preventative maintenance on the Kvant 2 gyrodynes in late November, using the attitude control jets to maintain station orientation while the gyrodynes were inactive.[2]

On December 8, the crew reconfigured the docking port at the front of the Mir base block to prepare it to receive the 1996 Priroda module. They moved the Konus docking unit from the +Z to the -Z docking port where Priroda would attach in the spring.[2]

Progress M-29 departs

Progress M-29 departed the station on December 19. It undocked from the rear Kvant port and deorbited over the Pacific Ocean.[2]

December 20, 1995 - February 22, 1996

Progress M-30 resupplies Euromir 95

Progress M-30 was launched from Baikonur Cosmodrome on a Soyuz-U rocket on December 18. It docked with the same port Progress M-29 departed from on December 20 with 2300 kg of fuel, crew supplies, and research/medical equipment for use on the extended Euromir 95 mission.[2]

Experiments continue

Reiter took biomedical samples and measurements and tested the capacity of uncooled melts in the TITUS materials processing furnace.[2] The Russian cosmonauts studied microgravity effects on hydrodynamics with the Volna-2 device, using models of spacecraft fuel system elements. They also investigated the possible links between terrestrial seismic activity and high-energy charged cosmic particle fluxes with the Maria magnetic spectrometer.[2]

Kvant Coolant Loop reactivation and third Mir 20 (second Euromir 95) EVA

Between January 12 and 16, the cosmonauts resumed work on the cooling system leak that began in November. They sealed a manifold on the coolant line and then refilled the loop with ethylene glycol that was sent up with Progress M-30.[2] The SPK (or YMK) maneuvering unit was stored inside the Kvant 2 airlock. It was a large unit which hadn't been used since it was tested in 1990 and it was in the way of airlock egress so Reiter and Gidzenko moved it outside on a February 8 EVA and attached it outside.[2] They also retrieved the two cassettes they deployed in October. They also attempted to perform a task on the Kristall antenna, but TsUP canceled the antenna work when the cosmonauts were unable to loosen the bolts on the antenna.[2]

10th anniversary of the Mir Base Block

The Mir base block launched to orbit on February 20, 1986. On February 20, 1996, ITAR-TASS reported a 'holiday atmosphere' aboard the complex. Having already remained in orbit for four years longer than originally intended, the station held the promise of at least three more orbiting anniversaries.[2]

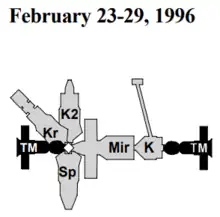

February 23–29, 1996

Progress M-30 undocked and Soyuz TM-23 launched

On February 21, Soyuz TM-23 launched from Baikonur Cosmodrome with the cosmonauts for Mir Principle Expedition 21. To clear a docking port for the Soyuz TM-23, the Progress M-30 was undocked on February 22 and re-entered over the Pacific Ocean.[2] The Soyuz docked on February 23 at the +X docking port on the rear of the Kvant module.[3] An hour and a half after docking, the hatches opened and Yuri Onufrienko and Yury Usachov were greeted by the Mir 20/Euromir 95 crew.[3] This began a week of joint operations where Mir 20 handed the station over to Mir 21, including familiarization with the current conditions of the projects and the station itself.[3] Two days before the return flight, a water leak appeared in the Mir base block, but the cosmonauts were able to repair it.[3]

Mir 20/Euromir 95 mission ends

Gidzenko, Avdeyev and Reiter donned their Sokol launch and reentry suits and entered the Soyuz TM-22 on February 29, 1996.[3] They landed safely about 105 km from Arkalyk. Their mission lasted 179 days, 1 hour and 42 minutes. Reiter then held the record for spaceflight duration by a Western European.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 The mission report is available here: http://www.spacefacts.de/mission/english/soyuz-tm22.htm

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 "Nasa History - Mir20" (PDF). nasa.gov.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "NASA History - Mir21" (PDF).

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 "Soyuz TM-22". weebau.com. Retrieved 2021-09-05.

- ↑ "Soyuz TM-22". www.astronautix.com. Archived from the original on July 26, 2016. Retrieved 2021-09-05.