| Mongol | |

|---|---|

American theatrical release poster | |

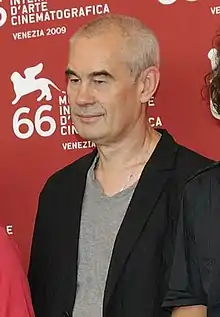

| Directed by | Sergei Bodrov |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Tuomas Kantelinen |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 125 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Languages | |

| Budget | $18 million[3] |

| Box office | $26.5 million[3] |

Mongol (Монгол), also known as Mongol: The Rise of Genghis Khan in the United States and Mongol: The Rise to Power of Genghis Khan in the United Kingdom, is a 2007 period epic film directed by Sergei Bodrov, about the early life of Temüjin, who later came to be known as Genghis Khan. The storyline was conceived from a screenplay written by Bodrov and Arif Aliev. It was produced by Bodrov, Sergei Selyanov, and Anton Melnik and stars Tadanobu Asano, Sun Honglei, and Chuluuny Khulan in the main roles. Mongol explores abduction, kinship, and the repercussions of war.[4]

The film was a co-production between companies in Russia, Germany and Kazakhstan. Filming took place mainly in the People's Republic of China, principally in Inner Mongolia (the Mongol autonomous region), and in Kazakhstan. Shooting began in September 2005, and was completed in November 2006. After an initial screening at the Russian Film Festival in Vyborg on 10 August 2007, Mongol was released in Russia on 20 September 2007. It saw a limited release in the United States on 6 June 2008 grossing $5.7 million in domestic ticket sales. It additionally earned nearly $21 million in sales through international release for a combined $26.5 million in gross revenue. The film was a minor financial success after its theatrical run, and was generally met with positive critical reviews. The film was nominated for the 2007 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film as a submission from Kazakhstan.[5]

The film is intended to be the first part of a trilogy about Genghis Khan, and initial work on the second part began in 2008.[6] The trilogy project was eventually put on the shelf, but in July 2013, during a visit to the annual Naadam Festival in Ulan Bator, Bodrov told the press that the production of the sequel had started, and that it may be shot in Mongolia,[7] as had been the intention for Mongol, before local protests, fearing that the film would not correctly portray the Mongolian people and their national hero, Genghis Khan, caused the shooting to move to Inner Mongolia and Kazakhstan.[8]

Plot

In 1192, Temüjin, a prisoner in the Tangut kingdom, recounts his story through a series of flashbacks.

Embarking on an expedition 20 years earlier (1172), nine-year-old Temüjin is accompanied by his father Yesügei to select a girl as his future wife. He meets and chooses Börte, against his father's wishes. On their way home, Yesügei is poisoned by an enemy tribe; on his dying breath, he tells his son that he is now Khan. However, Targutai, Yesügei's lieutenant, proclaims himself as Khan and is about to kill his young rival. Prevented from doing so by the boy's mother, Targutai lets him go and vows to kill him as soon as he becomes an adult.

After falling through a frozen lake, Temüjin is rescued by Jamukha. The two quickly become friends and take an oath as blood brothers. Targutai later captures him, but he escapes under the cover of night and roams the countryside.

Years later (1186), Temüjin is once again apprehended by Targutai. He escapes a second time, finding Börte and presenting her to his family. Later that night, they are attacked by the Merkit tribe. While being chased on horseback, Temüjin is shot with an arrow but survives. Börte, however, is kidnapped and taken to the Merkit camp.[4]

Temüjin goes to Jamukha—who is now his tribe's Khan—and seeks his help in rescuing his wife. Jamukha agrees, and after a year, they launch an attack on the Merkits and are successful. One night, while celebrating their victory, Temüjin demonstrates his generosity by allowing his troops to take an equal share of the plunder. Two of Jamukha's men see this as a stark contrast to their Khan's behavior and desert him the next morning by following their new master. Jamukha chases him down and demands that he give his men back, to which he refused. This act, aggravated by the inadvertent killing of his biological brother by one of Temüjin's men, leaves Jamukha (with Targutai as an ally) no choice but to declare war on him. Outnumbered, Temüjin's army is quickly defeated. Sparing his blood brother, Jamukha decides to sell him into slavery.[4]

Temüjin is sold to a Tangut nobleman despite the dire warning given to him by a Buddhist monk acting as his adviser, who senses the great potential the warrior carries and his future role in subjugating the Tangut State. While he is imprisoned, the monk pleads with him to spare his monastery when he will destroy the kingdom sometime in the future. In exchange for delivering a bone fragment to Börte indicating that he is still alive, Temüjin agrees. The monk succeeds in delivering the bone and the message at the cost of his life. Börte infiltrates the Tangut border town disguised as a merchant's concubine and the two escape.

Temüjin pledges to unify all of the Mongol tribes and imposes three basic laws for them to abide to: never kill women and children, always honor your promises and repay your debts, and never betray your Khan. Subsequently, (1196), he gathers an army and engages Jamukha, who has an even larger force. During the battle, a thunderstorm arises on the steppe, terrifying Jamhukha's and Temujin's armies, who cower in fear. However Temujin does not cower, and when his army sees him riding unafraid they are inspired to also be fearless and charge Jamukha's helpless and cowering army, which surrenders immediately. Temüjin allows Jamukha to live and brings the latter's army under his banner. Targutai is killed by his own soldiers and his body is presented to the Khan as a way of appeasing him, but they are executed for disobeying the law.

A postscript indicates that by 1206, Temüjin was designated the Khan of all the Mongols—Genghis Khan of the Great Steppe. He would later go on to invade and conquer the Tangut kingdom by 1227, fulfilling the monk's prophecy, but spared the monastery, honoring his debt to the monk.[4]

Cast

- Tadanobu Asano as Genghis Khan/Temüjin

- Odnyam Odsuren as young Temüjin

- Sun Honglei as Jamukha

- Amarbold Tuvshinbayar as young Jamukha

- Chuluuny Khulan as Börte

- Bayertsetseg Erdenebat as young Börte

- Amadu Mamadakov as Targutai

- Ba Sen as Yesügei

- Sai Xing Ga as Chiledu

- Bu Ren as Taichar

- Aliya as Oelun

- He Qi as Dai-Sechen

- Deng Ba Te Er as Daritai

- Zhang Jiong as Garrison Chief

- Ben Hon Sun as Monk

Production

Development

The premise of Mongol is the story of Genghis Khan, the Mongol leader who founded the Mongol Empire, which ruled expansive areas of Eurasia. The film depicts the early life of Temüjin, not as an evil war-mongering brute, but rather an inspiring visionary leader. Director Bodrov noted that "Russians lived under Mongolian rule for around 200 years" and that "Genghis Khan was portrayed as a monster". During the 1990s, Bodrov read a book by Russian historian Lev Gumilev entitled The Legend of the Black Arrow, which offered a more disciplined view of the Mongol leader and influenced Bodrov to create a film project about the warrior.

Bodrov spent several years researching the aspects of his story, discovering that Temüjin was an orphan, a slave and a combatant whom everyone tried to kill. He found difficulty in preparing the screenplay for the film due to the fact that no contemporary Mongol biography existed. The only Mongol history from the era is The Secret History of Mongols, written for the Mongol royal family some time after Genghis Khan's death in AD 1227. Author Gumilev had used the work as a historical reference and a work of significant literature. Casting for the film took place worldwide, including Mongolia, China, Russia, and in Los Angeles. Speaking on the choice of Tadanobu Asano to portray Temüjin, Bodrov commented that although it might have seemed odd to cast a Japanese actor in the role, he explained that the Mongol ruler was seen by many Japanese as one of their own. Bodrov said, "The Japanese had a very famous ancient warrior who disappeared [Minamoto no Yoshitsune], and they think he went to Mongolia and became Genghis Khan. He's a national hero, Genghis Khan. Mongolians can claim he's Mongolian, but the Japanese, they think they know who he is." Bodrov felt casting actor Sun Honglei as Jamukha was a perfect mix of "gravity and humor" for the role. Describing the character interaction between Asano and Honglei, he noted "They're completely different people, Temüjin and Jamukha, but they have a strong relationship, strong feelings between them." Aside from the Chinese and Japanese actors for those roles, the rest of the cast were Mongolian. It marked the first time a tale of Genghis Khan would be acted by Asians, this in contrast to such Hollywood and European attempts like the 1956 movie flop The Conqueror and the 1965 film Genghis Khan with Omar Sharif.

The film was initially intended to be shot in Mongolia, but the plans caused much protest in the country, as many Mongolians feared that it would not correctly portray their people and their national hero.[8] As a consequence, shooting was moved to the Chinese autonomous region Inner Mongolia and to Kazakhstan.

Filming

Filming began in 2005, lasting 25 weeks and taking place in China, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan. Production designer Dashi Namdakov helped to recreate the pastoral lifestyle of the nomadic tribesmen. Namdakov is originally from a Russian region which borders Mongolia and is home to many ethnic Mongols. Bodrov remarked, "Dashi has the Mongol culture in his bones and knows how to approach this material." To help create some of the horse-mounted stunt sequences, Bodrov called upon seasoned stuntmen from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, whom he was familiar with from the production of Nomad. Describing some of the stunt work, Bodrov claimed: "Not a single horse was hurt on this film. There's a line in the movie, when young Jamukha tells Temüjin, 'For Mongol, horse is more important than woman.' And that's how it is with the Kazakh and Kyrgyz stunt people. They took very good care of the horses and were very conscientious." Bodrov collaborated on the film with editors Zach Staenberg and Valdís Óskarsdóttir.

Release

Mongol was first released in Russia and Ukraine on 20 September 2007.[9] The film then premiered in cinemas in Turkey on 14 March 2008. Between April and December 2008, Mongol was released in various countries throughout the Middle East, Europe and Africa.[9] France, Algeria, Monaco, Morocco and Tunisia shared a release date of 9 April 2008. In the United States and the United Kingdom, the film was released on 6 June 2008. In 2009, certain Asian Pacific countries such as Singapore and Malaysia saw release dates for the film.[9] Within Latin America, Argentina saw a release for the film on 11 March, while Colombia began screenings on 9 April. The film grossed $20,821,749 in non-US box office totals.[9]

US box office

In the United States, the film premiered in cinemas on 6 June 2008. During its opening weekend, the film opened in 22nd place grossing $135,326 in business showing at five locations.[3] The film's revenue dropped by 17% in its second week of release, earning $112,212. For that particular weekend, the film fell to 25th place screening in five theaters. During the film's final release week in theaters, Mongol opened in a distant 80th place with $11,503 in revenue.[10] The film went on to top out domestically at $5,705,761 in total ticket sales through a 14-week theatrical run. Internationally, the film took in an additional $20,821,749 in box office business for a combined worldwide total of $26,527,510.[3] For 2008 as a whole, the film would cumulatively rank at a box office performance position of 167.[11]

Home media

Following its cinematic release in theaters, the Region 1 Code widescreen edition of the film was released on DVD in the United States on 14 October 2008. Special features for the DVD include scene selections, subtitles in English and Spanish, and subtitles in English for the hearing-impaired.[12]

The widescreen high-definition Blu-ray Disc version of the film was also released on 14 October 2008. Special features include; scene selections and subtitles in English and Spanish.[13] A supplemental viewing option for the film in the media format of video on demand is currently available too.[14]

Reception

Critical response

Among mainstream critics in the U.S., the film received mostly positive reviews. Rotten Tomatoes reported that 87% of 104 sampled critics gave the film a positive review, with an average score of 7.10 out of 10. The site's critics' consensus reads: "The sweeping Mongol mixes romance, family drama, and enough flesh-ripping battle scenes to make sense of Ghenghis Khan's legendary stature."[15] At Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average out of 100 to critics' reviews, the film received a score of 74 based on 27 reviews, indicating "Generally favorable reviews".[16] However, the film was criticized in Mongolia for factual errors and historical inaccuracies.[17]

Claudia Puig of USA Today said the film "has a visceral energy with powerful battle sequences and also scenes of striking and serene physical beauty." Noting a flaw, she did comment that Mongol might have included "one battle too many." Although overall, she concluded the film was "an exotic saga that compels, moves and envelops us with its grand and captivating story."[18]

| "Centered on the rise of Genghis Khan, the film is an enthralling tale, in the style of a David Lean saga, with similarly gorgeous cinematography. It combines a sprawling adventure saga with romance, family drama and riveting action sequences." |

| —Claudia Puig, writing in USA Today[18] |

Jonathan Kiefer, writing in the Sacramento News & Review, said "At once sweeping and intimately confidential, with durably magnetic performances by Japan's Asano Tadanobu as the adored warlord and China's Honglei Sun as Jamukha, his blood brother and eventual enemy, Mongol, a 2007 Best Foreign Language Film Oscar nominee, has to be by far the best action epic of 12th- and 13th-century Asian nomads you'll see". He emphatically believed Bodrov's film was "both ancient and authentic." He added that it was "commendably unhurried, and the scope swells up in a way that feels organic to a character-driven story".[19]

Walter Addiego, writing for the San Francisco Chronicle, said that the film offers "everything you would want from an imposing historical drama: furious battles between mass armies, unquenchable love between husband and wife, blood brothers who become deadly enemies, and many episodes of betrayal and treachery". Concerning cinematography, he believed the film included "plenty of haunting landscapes, gorgeously photographed by Sergei Trofimov on location in China, Kazakhstan and Mongolia, along with the sort of warfare scenes that define epics".[20]

Writing for The Boston Globe, Wesley Morris said that Mongol "actually works as an old-fashioned production - one with breathtaking mohawks, a scary yoking, one daring escape, hottish sex, ice, snow, braying sheep, blood oaths, dehydrating dunes, throat singing, a nighttime urination, kidnapping, charged reunions, and relatively authentic entertainment values."[21]

Writing for the Chicago Sun-Times, film critic Roger Ebert called the film a "visual spectacle, it is all but overwhelming, putting to shame some of the recent historical epics from Hollywood." Summing up, Ebert wrote "The nuances of an ancient and ingeniously developed culture are passed over, and it cannot be denied that Mongol is relentlessly entertaining as an action picture."[22]

| "Mongol is a ferocious film, blood-soaked, pausing occasionally for passionate romance and more frequently for torture." |

| —Roger Ebert, writing for the Chicago Sun-Times[22] |

A. O. Scott of The New York Times stated that Mongol was a "big, ponderous epic, its beautifully composed landscape shots punctuated by thundering hooves and bloody, slow-motion battle sequences."[23] Scott approved of how the film encompassed "rich ethnographic detail and enough dramatic intrigue to sustain a viewer's interest through the slower stretches."[23]

Similarly, Joe Morgenstern wrote in The Wall Street Journal that the film consisted of battle scenes which were as "notable for their clarity as their intensity; we can follow the strategies, get a sense of who's losing and who's winning. The physical production is sumptuous." Morgenstern affirmed that Mongol was "an austere epic that turns the stuff of pulp adventure into a persuasive take on ancient history."[24]

Lisa Schwarzbaum, writing for Entertainment Weekly, lauded the visual qualities of the film, remarking how Mongol "contrasts images of sweeping landscape and propulsive battle with potent scenes of emotional intimacy", while also referring to its "quite grand, quite exotic, David Lean-style epic" resemblance.[25]

Kyle Smith of the New York Post commented that the film combined the "intelligence of an action movie with the excitement of an art-house release" making Mongol "as dry as summer in the Gobi Desert." Smith did compliment director Bodrov on staging a "couple of splattery yet artful battle scenes", but concluded that the film "really isn't worth leaving your yurt for."[26]

Author Tom Hoskyns of The Independent described the film as being "very thin plot-wise." Hoskyns commended the "desolate landscapes and seasonal variations", but he was not excited about the repetitious nature of the story showing the "hero getting repeatedly captured and escaping."[27]

Joshua Rothkopf of Time Out said that Mongol was a "Russian-produced dud." He said that it included "ridiculous dialogue and Neanderthal motivations" as well as bearing "little relation to the raw, immediate work of his countrymates—like Andrei Tarkovsky, whose epic Andrei Rublev really gives you a sense of the dirt and desperation."[28]

Accolades

The film was nominated and won several awards in 2007–09. Various critics included the film on their lists of the top 10 best films of 2008. Mike Russell of The Oregonian named it the fifth-best film of 2008,[29] Lawrence Toppman of The Charlotte Observer named it the eighth-best film of 2008,[29] and V.A. Musetto of the New York Post also named it the eighth-best film of 2008.[29]

| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80th Academy Awards[30] | Best Foreign Language Film | Nominated | |

| 2007 Asia Pacific Screen Awards[31] | Best Achievement in Cinematography | Sergey Trofimov | Nominated |

| 2nd Asian Film Awards[32] | Best Supporting Actor | Sun Honglei | Won |

| Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards 2008[33] | Best Foreign Language Film | Nominated | |

| European Film Awards 2008[34][35] | Best Cinematographer | Sergey Trofimov, Rogier Stoffers | Nominated |

| Best European Film | Sergey Bodrov | Nominated | |

| 6th Golden Eagle Awards[36] | Best Costume Design | Karin Lohr | Won |

| Best Sound Design | Stephan Konken | Won | |

| 2009 40th NAACP Image Awards[37] | Outstanding Foreign Motion Picture | Nominated | |

| Las Vegas Film Critics Society Awards 2008[38] | Best Foreign Language Film | Won | |

| 2008 National Board of Review of Motion Pictures Awards[39] | Best Foreign Language Film | Won | |

| 2008 Nika Awards[40] | Best Cinematography | Sergey Trofimov, Rogier Stoffers | Won |

| Best Costume Design | Karin Lohr | Won | |

| Best Director | Sergey Bodrov | Won | |

| Best Film | Won | ||

| Best Production Design | Dashi Namdakov, Yelena Zhukova | Won | |

| Best Sound | Stephan Konken | Won |

Sequel

The Great Khan (Великий Хан) is the provisional title[41] for the second installment of Bodrov's planned trilogy on the life of Temüjin, Genghis Khan. The Mongolian pop singer, Amarkhuu Borkhuu, was offered a role, but declined.[42] The trilogy project was eventually put on the shelf, but in July 2013, during a visit to the annual Naadam Festival in Ulan Bator, Bodrov told the press that the production of the sequel had started again.[7] The sequel is now called "Mongol II: The Legend" and started its shooting in 2019.[43]

Soundtrack

The soundtrack for Mongol, was released in the United States by the Varèse Sarabande music label on 29 July 2008.[44] The score for the film was composed by Tuomas Kantelinen, with additional music orchestrated by the Mongolian folk rock band Altan Urag.[45]

| Mongol: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack | |

|---|---|

| Film score by | |

| Released | 07/29/2008 |

| Length | 43:39 |

| Label | Varèse Sarabande |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Beginning" | 4:35 |

| 2. | "At the Fireplace: Composed and Performed by Altan Urag" | 0:48 |

| 3. | "Blood Brothers" | 1:08 |

| 4. | "Chase 1: Composed and Performed by Altan Urag" | 0:51 |

| 5. | "Fighting Boys" | 0:53 |

| 6. | "Temüjin's Escape" | 2:03 |

| 7. | "Funeral and Robbery: Composed and Performed by Altan Urag" | 2:30 |

| 8. | "Together Now" | 1:52 |

| 9. | "Love Theme" | 1:25 |

| 10. | "Chase 2: Composed and Performed by Altan Urag" | 1:36 |

| 11. | "Cold Winter" | 2:30 |

| 12. | "Merkit Territory" | 1:53 |

| 13. | "Attack" | 0:44 |

| 14. | "Martial Rage" | 1:12 |

| 15. | "Jamukha is Following" | 1:30 |

| 16. | "Slavery" | 1:48 |

| 17. | "Long Journey" | 0:49 |

| 18. | "Destiny" | 1:49 |

| 19. | "Joy in Mongolia: Composed and Performed by Altan Urag" | 3:07 |

| 20. | "Final Battle, Showing Strength" | 2:15 |

| 21. | "Final Battle, Tactical Order" | 0:36 |

| 22. | "Final Battle, The First Attachment" | 1:21 |

| 23. | "Final Battle, Death by Arrows" | 1:55 |

| 24. | "Tengri's Help" | 0:57 |

| 25. | "Victory to Khan" | 1:36 |

| 26. | "No Mercy" | 1:56 |

| Total length: | 43:39 | |

See also

References

- ↑ "MONGOL (15)". British Board of Film Classification. 31 March 2009. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ↑ "Mongol". Lumiere. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "Mongol". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Sergei Bodrov. (2007). Mongol [Motion picture]. Russia: Picturehouse Entertainment.

- ↑ "80th Academy Awards Nominations Announced" (Press release). Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 22 January 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ↑ Birchenough, Tom (14 May 2008). "Bodrov kicks off production unit". Variety Asia. Reed Business Information. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- 1 2 InfoMongolia, 6 August 2013: "Russian Producer Announces the Sequel to 'Mongol'" Archived 9 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine Linked 2013-08-29

- 1 2 Variety, 10 April 2005: "Mongols protest Khan project". Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- 1 2 3 4 "International Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "September 5–7, 2008 Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "2008 Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "Mongol DVD Widescreen". BarnesandNoble.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ↑ "Mongol Blu-ray Widescreen". BarnesandNoble.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ↑ "Mongol VOD Format". Amazon. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ↑ "Mongol (2008)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ↑ "Mongol: The Rise of Genghis Khan Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ↑ Г. Жигжидсvрэн: Сергей Бодровын "Монгол" кинонд бvтээсэн дvр байхгvй Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. olloo.mn. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- 1 2 Puig, Claudia (12 June 2008). Tepid 'Mongol' A sweeping historic tale. USA Today. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- ↑ Kiefer, Jonathan (26 June 2008). I think I Khan Mongol. Sacramento News & Review. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- ↑ Addiego, Walter (20 June 2008). Review: 'Mongol' revisits Genghis Khan. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- ↑ Morris, Wesley (20 June 2008). When blood runs hot and cold. The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- 1 2 Ebert, Roger (20 June 2008). Mongol Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- 1 2 Scott A.O., (6 June 2008). Forge a Unity of Purpose, Then Conquer the World. The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- ↑ Morgenstern, Joe (6 June 2008). 'Mongol' Brings Style And Sumptuous Scale To Genghis Khan Saga. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- ↑ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (6 June 2008). Mongol (2008) Archived 20 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- ↑ Smith, Kyle (6 June 2008). Sweet Mongolia: How Genghis Got His Horde Archived 22 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. New York Post. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- ↑ Hoskyns, Tom (26 September 2008). DVD: Mongol. The Independent. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- ↑ Rothkopf, Joshua (11 June 2008). Mongol: The Rise to Power of Genghis Khan. Time Out. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- 1 2 3 "Metacritic: 2008 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ↑ "Nominees & Winners for the 80th Academy Awards". Oscars.org. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "The Awards". Asia Pacific Screen Awards. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "Nominations & Winners". Asian Film Awards. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "The 14th Critics' Choice Movie Awards Nominees". BFCA.org. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "Nominations for the European Film Awards 2008". EuropeanFilmAcademy.org. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "The People's Choice Award 2008". EuropeanFilmAcademy.org. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "Nominees & Winners". KinoAcademy.ru. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "40th NAACP Image Awards". NAACP Image Awards. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ↑ "2008 Sierra Award winners". lvfcs.org. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "Awards for 2008". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "Award Winners & Nominees". Nika Awards. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ↑ "Bodrov launches production company, Director's first project to be a 'Mongol'". Variety. 16 May 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ "Б.АМАРХҮҮ С.БОДРОВТ ГОЛОГДЖЭЭ" (in Mongolian). Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ↑ "Getaway Pictures".

- ↑ "Mongol Original Motion Picture Soundtrack". BarnesandNoble.com. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ↑ "Mongol (2008)". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

External links

- Mongol at IMDb

- Mongol at Box Office Mojo

- Mongol at Rotten Tomatoes

- Mongol at Metacritic