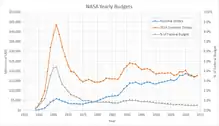

As a federal agency, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) receives its funding from the annual federal budget passed by the United States Congress. The following charts detail the amount of federal funding allotted to NASA each year over its history to pursue programs in aeronautics research, robotic spaceflight, technology development, and human space exploration programs.

Annual budget

NASA's budget for financial year (FY) 2020 is $22.6 billion.[1] It represents 0.48% of the $4.7 trillion the United States plans to spend in the fiscal year.[2]

Since its inception the United States has spent nearly US$650 billion (in nominal dollars) on NASA.

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes for table: Sources for a part of these data:

- U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) (needs proper citation-link, numbers here differ from NASA Pocket Statistics)

- Air Force Association's Air Force Magazine 2007 Space Almanac

- "NASA 2010 Budget" (PDF). govinfo.gov. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

- "Consumer Price Index, 1913-". minneapolisfed.org. Retrieved May 13, 2023.

Cost of Apollo program

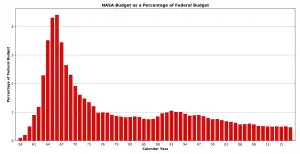

NASA's budget peaked in 1964–66 when it consumed roughly 4% of all federal spending. The agency was building up to the first Moon landing and the Apollo program was a top national priority, consuming more than half of NASA's budget and driving NASA's workforce to more than 34,000 employees and 375,000 contractors from industry and academia.[20]

In 1973, NASA submitted congressional testimony reporting the total cost of Project Apollo as $25.4 billion (about $176 billion in 2022 dollars).[21]

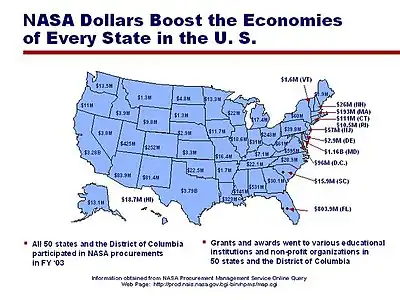

Economic impact of NASA funding

A November 1971 study of NASA released by MRIGlobal (formerly Midwest Research Institute) of Kansas City, Missouri concluded that "the $25 billion in 1958 dollars spent on civilian space R & D during the 1958–1969 period has returned $52 billion through 1971 – and will continue to produce payoffs through 1987, at which time the total pay-off will have been $181 billion. The discounted rate of return for this investment will have been 33 percent."[22]

Other statistics on NASA's economic impact may be found in the 1976 Chase Econometrics Associates, Inc. reports[23] and backed by the 1989 Chapman Research report, which examined 259 non-space applications of NASA technology during an eight-year period (1976–1984) and found more than:

- $21.6 billion in sales and benefits

- 352,000 (mostly skilled) jobs created or saved

- $355 million in federal corporate income taxes

According to a 1992 Nature commentary, these 259 applications represent ". . .only 1% of an estimated 25,000 to 30,000 Space program spin-offs."[24]

A 2013 report prepared by the Tauri Group for NASA showed that NASA invested nearly $5 billion in U.S. manufacturing in FY 2012, with nearly $2 billion of that going to the technology sector. NASA also develops and commercializes technology, some of which can generate over $1 billion in revenue per year over multiple years[25]

In 2014, the American Helicopter Society criticized NASA and the government for reducing the annual rotorcraft budget from $50 million in 2000 to $23 million in 2013, impacting commercial opportunities.[26]

The 2017 Economic Impact Report prepared by NASA for their Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) awards found that for FY 2016, these programs created 2,412 jobs, $474 million in economic output, and $57.3 million in fiscal impact with an initial investment of $172.9 million.[27]

Public perception

The perceived national security threat posed by early Soviet leads in spaceflight drove NASA's budget to its peak, both in real inflation-adjusted dollars and in a percentage of the total federal budget (4.41% in 1966). But the apparent U.S. victory in the Space Race — landing men on the Moon — erased the perceived threat, and NASA was unable to sustain political support for its vision of an even more ambitious Space Transportation System entailing reusable Earth-to-orbit shuttles, a permanent space station, lunar bases, and a human mission to Mars. Only a scaled-back space shuttle was approved, and NASA's funding leveled off at just under 1% in 1976, then declined to 0.75% in 1986. After a brief increase to 1.01% in 1992, it declined to about 0.5% in 2013.

To help with public perception and to raise awareness regarding the widespread benefits of NASA-funded programs and technologies, NASA instituted the Spinoffs publication. This was a direct offshoot of the Technology Utilization Program Report, a "publication dedicated to informing the scientific community about available NASA technologies, and ongoing requests received for supporting information." according to the NASA Spinoff about page the technologies in these reports created interest in the technology transfer concept, its successes, and its use as a public awareness tool. The reports generated such keen interest by the public that NASA decided to make them into an attractive publication. Thus, the first four-color edition of Spinoff was published in 1976.[28]

The American public, on average, believes NASA's budget has a much larger share of the federal budget than it actually does. A 1997 poll reported that Americans had an average estimate of 20% for NASA's share of the federal budget, far higher than the actual 0.5% to under 1% that has been maintained throughout the late '90s and first decade of the 2000s.[29] It is estimated that most Americans spent less than $9 on NASA through personal income tax in 2009.[30]

However, there has been a recent movement to communicate discrepancy between perception and reality of NASA's budget as well as lobbying to return the funding back to the 1970–1990 level. The United States Senate Science Committee met in March 2012 where astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson testified that "Right now, NASA's annual budget is half a penny on your tax dollar. For twice that—a penny on a dollar—we can transform the country from a sullen, dispirited nation, weary of economic struggle, to one where it has reclaimed its 20th-century birthright to dream of tomorrow."[31][32] Inspired by Tyson's advocacy and remarks, the Penny4NASA campaign was initiated in 2012 by John Zeller and advocates the doubling of NASA's budget to one percent of the Federal Budget, or one "penny on the dollar."[33]

In 2018, Business Insider surveyed approximately 1,000 US residents to determine what they believed was the annual NASA budget. The average respondent estimated that NASA's budget was 6.4% of annual federal spending, when it was actually 0.5%. In a follow-up question, 85% of respondents stated that NASA funding should be increased, despite the majority of responses overestimating NASA's actual budget.[34]

Political opposition to NASA funding

Public opposition to NASA and its budget dates back to the Apollo era. Critics have cited more immediate concerns, like social welfare programs, as reasons to cut funding to the agency.[35] Furthermore, they have questioned the return on investment (ROI) feasibility of NASA's research and development. In 1968, physicist Ralph Lapp argued that if NASA really did have a positive ROI, it should be able to sustain itself as a private company, and not require federal funding.[35] More recently, critics have faulted NASA for sinking money into the Space Shuttle program, reducing funding available for its long-term missions to Mars and deep space.[36] Human missions to Mars have also been denounced for their inefficiency and large cost compared to uncrewed missions.[37] In the 2010s, Republicans in congress increasingly opposed the Earth science aspects of NASA spending, arguing that spending on Earth science programs such as climate research was in pursuit of political agendas.[38]

See also

References

- ↑ "NASA's FY 2020 Budget". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- ↑ White House Office of Management and Budget "Table 1.1—Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits (-): 1789–2024|language=en-US|access-date=2019-12-31}"

- ↑ The National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA) was the precursor to NASA. It was subsumed by the new agency under the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958, ceasing on October 1, 1958.

- ↑ "Appendix C". history.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- 1 2 % of total federal expenditures from: "NASA budgets: US spending on space travel since 1958 UPDATED". TheGuardian.com. February 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- 1 2 1999–2010 based on federal outlays from: Federal budget (United States)#Total outlays in recent budget submissions

- ↑ "2011 Budget Overview" (PDF). nasa.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-01. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- ↑ Berger, Brian (2011-04-13). "U.S. Budget Compromise Includes $18.5 Billion for NASA". Space.com. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ↑ "NASA FY 2013 President's Budget Request Summary" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 6, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- ↑ "NASA FY 2014 President's Budget Request Summary" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- ↑ "NASA FY 2015 President's Budget Request" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- ↑ "2016 NASA Budget Estimates" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- ↑ Clark, Stephen (2014-12-14). "NASA gets budget hike in spending bill passed by Congress". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- ↑ "Agency fact sheet: NASA's FY 2017 budget request" (PDF). 2016. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ↑ "S.442 – National Aeronautics and Space Administration Transition Authorization Act of 2017". Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ↑ "NASA receives $20.7 billion in omnibus appropriations bill". Science News. 22 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ Smith, Marcia. "NASA's FY 2019 Budget Fact Sheet" (PDF). Space Policy Online. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ↑ "National Aeronautics and Space Administration FY 2021 President's Budget Requests Summary" (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ↑ "National Aeronautics and Space Administration FY 2022 President's Budget Requests Summary" (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ↑ Levine, Arnold S. (1983). "Chapter 4: The NASA Acquisition Process: Contracting For Research and Development". Managing NASA in the Apollo era : an administrative history of the U.S. civilian space program, 1958-1969. Scientific and Technical Information Branch, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. OCLC 317074611.

- ↑ United States. Congress. House. Committee on Science and Astronautics. (1973). 1974 NASA authorization: hearings, Ninety-third Congress, first session, on H.R. 4567. Page 1271. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

- ↑ "Economic Impact of Stimulated Economic Activity.". nasa.gov. Retrieved 14 Nov. 2018.

- ↑ "The Economic Impact of NASA R&D Spending: Preliminary Executive Summary.", April 1975. Also: "Relative Impact of NASA Expenditure on the Economy.", March 18, 1975

- ↑ Bezdek, Roger H.; Wendling, Robert M. (January 9, 1992). "Sharing out NASA's spoils". Nature. Nature Publishing Group. 355 (6356): 105–106. Bibcode:1992Natur.355..105B. doi:10.1038/355105a0. S2CID 46464236.

- ↑ "NASA Socio-Economic Impacts". Archived 2017-08-01 at the Wayback Machine National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 14 Nov. 2018.

- ↑ Hirschberg, Mike. "Investing in Tomorrow's Civil Rotorcraft" American Helicopter Society, July–August 2014. Accessed: 7 October 2014. Archived on 7 October 2014

- ↑ "2017 Economic Impact Report". nasa.gov. Retrieved 14 Nov. 2018.

- ↑ "About Spinoff". NASA. n.d. Archived from the original on 2014-12-08. Retrieved 26 Nov 2014.

- ↑ Launius, Roger D. "Public opinion polls and perceptions of US human spaceflight". Division of Space History, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ "Personal Income Tax Paid To NASA In 2009 By Income Level". NASACost.com.

- ↑ "Past, Present, and Future of NASA – U.S. Senate Testimony". Hayden Planetarium. 7 Mar 2012. Retrieved 4 Dec 2012.

- ↑ "Past, Present, and Future of NASA – U.S. Senate Testimony (Video)". Hayden Planetarium. 7 Mar 2012. Retrieved 4 Dec 2012.

- ↑ "Why We Fight – Penny4NASA". Penny4NASA. Retrieved 30 Nov 2012.

- ↑ Mosher, Dave; Lee, Samantha (December 18, 2018). "85% of Americans would give NASA a giant raise, but most don't know how little the space agency gets as a share of the federal budget". Insider. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- 1 2 "A Case for Cutting NASA's Budget". The New Republic. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- ↑ "NASA's Shuttle Program Cost $209 Billion — Was it Worth It?". Space.com. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- ↑ "Should NASA Ditch Manned Missions to Mars?". Space.com. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- ↑ Eric Berger (October 29, 2015) Republicans outraged over NASA earth science programs… that Reagan began. Ars Technica

External links

- NASA - Budget Documents, Strategic Plans and Performance Reports

- The Planetary Society - What is NASA's budget?

- Space Policy Online - What's a Markup? And other common questions about the federal process.