The National Volunteers was the name taken by the majority of the Irish Volunteers that sided with Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond after the movement split over the question of the Volunteers' role in World War I.

Origins

The National Volunteers were the product of the Irish political crisis over the implementation of Home Rule in 1912–14. The Third Home Rule Bill had been proposed in 1912 (and was subsequently passed in 1914) under the British Liberal government, after a campaign by John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party. However, its implementation was delayed in the face of mass resistance by Irish Unionists. This had begun with the introduction of the bill into Parliament, when thousands of unionists signed the "Ulster Covenant", pledging to resist Home Rule. In 1913 they formed the Ulster Volunteers (UVF), an armed wing of Ulster Unionism and organised locally by the Orange Order; the Ulster Volunteers stated that they would resist Home Rule by force.[1]

In response, Nationalists formed their own paramilitary group, the Irish Volunteers, at a meeting held in Dublin on 25 November 1913; the purpose of this new organisation was to safeguard the granting and implementation of Home Rule.[2] It looked for several months in 1914 as if civil war was imminent between the two armed factions, with the British Army known to be reluctant to intervene against Ulster armed opposition to Home Rule's coming into operation. While Redmond took no role in the creation of the Irish Volunteers, when he saw how influential they had become he realised an independent body of such magnitude was a threat to his authority as leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, and therefore sought control of the organisation.

Eoin MacNeill, along with Sir Roger Casement and other leaders of the Irish Volunteers, had indeed sought Redmond's approval of and input in the organisation, but did not want to hand control over to him. In June 1914, the Volunteer leadership reluctantly agreed, in the interest of harmony, to permit Redmond to nominate half of the membership of the Volunteer Executive;[3] as some of the standing members were already Redmondites, this would make his supporters a majority of the Volunteers' leadership. The motion was bitterly opposed by the radical members of the committee (mostly members of the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood), notably Patrick Pearse, Seán Mac Diarmada, and Éamonn Ceannt, but was carried nevertheless to prevent a split. With the support of the Irish Party the Volunteer organisation grew dramatically.

Great War split

Following the outbreak of World War I in August, and the successful placement of the Home Rule Act on the statute books (albeit with its implementation formally postponed), Redmond made a speech in Woodenbridge, County Wicklow on 20 September, in which he called for members of the Volunteers to enlist in an intended Irish Army Corps of Kitchener's New British Army. He pledged his support to the Allied cause, saying in his address:

The interests of Ireland — of the whole of Ireland — are at stake in this war. This war is undertaken in the defence of the highest principles of religion and morality and right, and it would be a disgrace for ever to our country and a reproach to her manhood and a denial of the lessons of her history if young Ireland confined their efforts to remaining at home to defend the shores of Ireland from an unlikely invasion, and to shrinking from the duty of proving on the field of battle that gallantry and courage which has distinguished our race all through its history. I say to you, therefore, your duty is twofold. I am glad to see such magnificent material for soldiers around me, and I say to you: "Go on drilling and make yourself efficient for the Work, and then account yourselves as men, not only for Ireland itself, but wherever the fighting line extends, in defence of right, of freedom, and religion in this war".[4]

Redmond's motives were twofold. Firstly, he felt it was in the future interest of an All-Ireland Home Rule settlement to support the British war cause, joining together with the Ulster Volunteers who offered immediate support by enlisting in the 36th (Ulster) Division. Secondly, he hoped that the Volunteers, with arms and training from the British, would become the nucleus of an Irish Army after Home Rule was implemented.[5] He reminded the Irish Volunteers that when they returned after an expected short war at the end of 1915, they would be an army capable of confronting any attempt to exclude Ulster from the operation of the Government of Ireland Act.

Militant nationalists reacted angrily against Redmond's support for the war, and nearly all of the original leaders of the Volunteers grouped together to dismiss his appointees. However, the great majority of the Volunteers supported Redmond, and became known as the National Volunteers.[4]

Recruitment for World War I

The vast majority of the Volunteer membership remained loyal to Redmond, bringing some 142,000 members to the National Volunteers, leaving the Irish Volunteers with just a rump, estimated at 9,700 members.[6] Many other Irish nationalists and parliamentary leaders, such as William O'Brien MP, Thomas O'Donnell MP, Joseph Devlin MP, and The O'Mahony, sided with Redmond's decision and recruited to support the British and Allied war effort. Five other MPs, J. L. Esmonde, Stephen Gwynn, Willie Redmond, William Redmond, and D. D. Sheehan, as well as former MP Tom Kettle, joined Kitchener's New Service Army during the war.

Many Irishmen enlisted voluntarily in Irish regiments of the New British Army, forming part of the 10th (Irish) and 16th (Irish) Divisions. Out of a National Volunteer membership of about 150,000, roughly 24,000 (about 24 battalions) were to join those Divisions for the duration of the war. Another 7,500 joined reserve battalions in Ireland.[7] The National Volunteers were therefore a minority among the 206,000 Irishmen who served as volunteers for the British Army in the war, and so failed to constitute a nascent Irish Army as Redmond had hoped.[6] Recruiting for the war among the National Volunteers, after an initial burst of enthusiasm, proved rather sluggish. According to historian Fergus Campbell, "most of the members of the National Volunteers were farmers' sons, and members of this social group were reluctant to join the colours".[8] A police report of late 1914 commented: "Though the large majority of the nominal National Volunteers approve of Mr. Redmond's pronouncement, only very few will enlist".[9] A contemporary writer felt that, "at the back of it was a vague feeling that to fight for the British Empire was a form of disloyalty to Ireland.[10]

Moreover, Redmond's hopes for an Irish Army Corps were also to end in disappointment for him. Instead, a New Army 16th (Irish) Division was created. The Division was largely officered by Englishmen (an exception was William Hickie, an Irish born general), which was not a popular decision in nationalist Ireland. This outcome was in part due to the lack of trained Irish officers; the few trained officers had been sent to the 10th Division, and those still available had been included into Sir Edward Carson's 36th (Ulster) Division. In addition, Redmond's earlier statement, that the Irish New Army units would return armed and capable of enforcing Home Rule, aroused War Office suspicions.[11]

The National Volunteers after 1914

The war's popularity in Ireland and the popularity of John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party were badly dented by the severe losses subsequently suffered by the Irish divisions. In addition, the postponement of the implementation of Home Rule damaged both the IPP and the National Volunteers.

The majority of the National Volunteers (over 120,000 or 80%) did not enlist in the British Army. John Redmond had intended that they would form an official home defence force for Ireland during the War, but the British War Office baulked at arming and training the Irish nationalist movement.[12] Military historian Timothy Bowman has described the situation as follows: "While Kitchener saw the UVF as an efficient military force and was prepared to offer concessions to secure the services of UVF personnel in the British army his view of the INV was very different. The INV were, even in comparison to the UVF, an inefficient military force in 1914, lacked trained officers, finances and equipment. Kitchener was certainly not inclined to, as he saw it, waste valuable officers and equipment on a force which, at best, would relieve Territorial units from garrison duties and, at worst, would provide Irish Nationalists with the ability to enforce Home Rule on their own terms.[13]

In fact, the National Volunteers fell into decline as the war went on. Their strength fell to around 100,000 by February 1916,[8] and moreover their companies tended to fall into inactivity. In many cases, this was put down to a fear of conscription being introduced into Ireland should they drill too openly.[8] For this reason, British sources reported by early 1916 that the National Volunteers as a movement were "practically dead" or "non-existent".[8]

The National Volunteers' other problem was a lack of leadership, as many of its most committed and militarily experienced members had enlisted in Irish Regiments for the war. As a result, the RIC (police) report on them concluded: "It is a strong force on paper, but without officers and untrained, it is little better than a large mob".[14] They staged a very large rally, of over 20,000 men, on Easter Sunday 1915 in Dublin's Phoenix Park, but their Inspector General, Maurice Moore, saw no military future for the organisation: "They cannot be trained, disciplined or armed, moreover, the enthusiasm has gone and they cannot be kept going... it will be of no practical use against any army, Orange or German."[15]

By contrast, the smaller but more militant Irish Volunteers increased in both numbers and activity as the War went on. The numerical increase was modest, from 9,700 in 1914 to 12,215 by February 1916, but they trained regularly and had kept most of the Volunteer weaponry.[8] By March 1916, the RIC was reporting that the Irish Volunteers, "are foremost among [nationalist] political societies, not by reason of their numerical strength but on account of their greater activity".[8] In April 1916, a faction within the Irish Volunteers launched the Easter Rising, an armed insurrection centred in Dublin aimed at the ending of British rule in Ireland. During the Rising, one unit of the National Volunteers (in Craughwell, County Galway), offered its services to the local RIC to help suppress the rebellion in that area.[16]

The rebellion was put down within a week by the British Army (including Irish units such as the Royal Dublin Fusiliers). In its aftermath, and especially after the Conscription Crisis of 1918 in which the British Cabinet had planned to impose conscription in Ireland, the National Volunteers were eclipsed by the Irish Volunteers, whose membership shot up to over 100,000 by the end of 1918.[17] John Redmond's Irish Parliamentary Party was similarly overtaken by the separatist Sinn Féin party in the general elections in December 1918.

After the Armistice in November 1918, around 100,000 Irishmen, including the surviving members of the National Volunteers who had enlisted, were demobilised from the British Army.[18]

Irish Republicanism had now displaced constitutional nationalism as represented by the Irish Parliamentary Party, leading to the Irish Declaration of Independence and the outbreak of armed conflict against the British (1919). The Third Home Rule Bill was never implemented, and was repealed by the Government of Ireland Act 1920 (the Fourth Home Rule Bill), which partitioned Ireland (1921).

References

- ↑ Townsend, Charles: 1916, The Easter Rising, pp. 33–34

- ↑ White, Gerry and O'Shea, Brendan: Irish Volunteer Soldiers 1913–23, p. 8, Osprey Publishing Oxford (2003), ISBN 978-1-84176-685-0

- ↑ Irish Volunteer Soldiers 1913–23, p. 8, ISBN 1-84176-685-2

- 1 2 O’Riordan, Tomás: UCC Multitext Project in Irish History John Redmond Archived 28 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Townshend, p. 73

- 1 2 Cambell, Fergus: Land and Revolution: Nationalist Politics in the West of Ireland, 1891–1921, p. 196

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, David: in Thomas Bartlet (ed.), A Military History of Ireland, p. 386

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Campbell, p. 197

- ↑ Townshend, p. 75

- ↑ Townsend, p. 75

- ↑ Bowman, Timothy: Irish Regiments in the Great War, Ch. 3: Raising the Service battalions, p. 62, Manchester University Press (2003) ISBN 0-7190-6285-3

- ↑ Townshend, p. 62

- ↑ Bowman, Timothy: Irish Regiments in the Great War, "Raising the Service battalions", p. 67, Manchester University Press (2003), ISBN 0-7190-6285-3

- ↑ Townsend, p. 70

- ↑ Townshend, p. 71

- ↑ Campbell, p. 215

- ↑ Collins, M. E.: Ireland 1868–1966, p. 242

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, Bartley, p. 397

Sources and further reading

- Thomas P. Dooley: Irishmen or English Soldiers?: The Times and World of a Southern Catholic Irish Man (1876–1916) Enlisting in the British Army During the First World War, Liverpool Press (1995).

- Terence Denman: Ireland's Unknown Soldiers: The 16th (Irish) Division in the Great War, Irish Academic Press (1992), ISBN 0-7165-2495-3.

- Desmond & Jean Bowen: Heroic Option: The Irish in the British Army, Pen & Sword Books (2005), ISBN 1-84415-152-2.

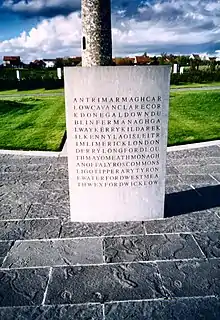

Great War memorials

Volunteers who died in the Great War are commemorated at the:

- Irish National War Memorial Gardens Dublin.

- Island of Ireland Peace Park Messines, Belgium.

- Menin Gate Memorial Ypres, Belgium.