| History of Bulgaria |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

Main category |

| Rise of nationalism in the Balkans Nationalism under the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

The National awakening of Bulgaria refers to the Bulgarian nationalism that emerged in the early 19th century under the influence of western ideas such as liberalism and nationalism, which trickled into the country after the French Revolution, mostly via Greece, although there were stirrings in the 18th century. Russia, as fellow Orthodox Slavs, could appeal to the Bulgarians in a way that Austria could not. The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca of 1774 gave Russia the right to interfere in Ottoman affairs to protect the Sultan's Christian subjects.

Background

The Bulgarian national revival is considered to have started with the work of Saint Paisius of Hilendar, who opposed Greek domination of Bulgaria's culture and religion. His work Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya ("History of the Slav-Bulgarians"), which appeared in 1762, was the first work of Bulgarian historiography. It is considered Paisius' greatest work and one of the greatest pieces of Bulgarian literature. In it, Paisius interpreted Bulgarian medieval history with the goal of reviving the spirit of his nation.

His successor was Saint Sophronius of Vratsa, who started the struggle for an independent Bulgarian church.

The first nationwide movement was for enlightenment. Educated Bulgarians started to finance the building of Bulgarian schools. In spite of Ottoman resistance, Bulgarians founded their own schools and started publishing textbooks. In that they received substantial aid from the American Protestant missionaries, who provided the first and only printing establishment in the Ottoman Empire in Smyrna (now Izmir), capable of printing Bulgarian Cyrillic.[1] The Greek revolt against the Ottomans in 1821 also influenced the small Bulgarian educated class. But Greek influence was limited by the general Bulgarian resentment of Greek control of the Orthodox Church in Bulgaria. It was the struggle to revive an independent Bulgarian church which first roused Bulgarian nationalist sentiment. When some Bulgarians threatened to abandon the Orthodox Church altogether and form a Bulgarian Uniate church loyal to Rome, Russia intervened with the Sultan. In 1870 a Bulgarian Exarchate was created by an edict of the Sultan, and the first Bulgarian Exarch (Antim I) became the natural leader of the emerging nation. The Patriarch of Constantinople responded by excommunicating the Bulgarian Exarchate, which reinforced their will for independence.

Another source of the Bulgarian national revival was the Romantic nationalist vision of a people sharing oral traditions and practices. These ideas were stimulated by the work of Johann Gottfried Herder in particular, and were reinforced by Russian Slavophiles and the model Serbian nationalism under the stimulus of scholar-publicists such as Vuk Karadžić. In Bulgaria, the scholar and newspaper editor Lyuben Karavelov played an important role in collecting and publishing oral traditions, and comparing them with the traditions of other Slavic peoples.

The "Big Four" of Bulgaria's independence struggle were Georgi Rakovski (Subi S. Popovich), Vasil Levski (Vasil Ivanov Kunchev), Lyuben Karavelov, and Hristo Botev. Rakovski outlined the first plan for Bulgaria independence, but died before he could put his plan in action. Levski, Karavelov, and Botev formed the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee, the first real independence organization, with a clear plan for revolution. But Levski was killed in 1873, and the committees inside Bulgaria broke down. A later dispute between Karavelov and Botev led to the end of the organisation.

Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate (a de facto autocephaly) was unilaterally (without the blessing of the Ecumenical Patriarch) promulgated on May 23 [O.S. May 11] 1872, in the Bulgarian church in Constantinople in pursuance of the March 12 [O.S. February 28] 1870 firman of Sultan Abdülaziz of the Ottoman Empire.

The foundation of the Exarchate was the direct result of the struggle of the Bulgarian Orthodox against the domination of the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople in the 1850s and 1860s. In 1872, the Patriarchate accused the Exarchate that it introduced ethno-national characteristics in the religious organization of the Orthodox Church, and the secession from the Patriarchate was officially condemned by the Council in Constantinople in September 1872 as schismatic. Nevertheless, Bulgarian religious leaders continued to extend the borders of the Exarchate in the Ottoman Empire by conducting plebiscites in areas contested by both Churches.[2]

In this way, in the struggle for recognition of a separate Church, the modern Bulgarian nation was created under the name Bulgar Millet.[3]

Bulgarian Exarchate was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and the Bulgarian Patriarchate was restored in 1953.

The April uprising

In April 1876 the Bulgarians revolted in the April uprising. It was organised by the Bulgarian Revolutionary Central Committee, and inspired by the insurrection in Bosnia and Herzegovina the previous year. The revolt was largely confined to the region of Plovdiv, certain districts in northern Bulgaria, Macedonia, and in the area of Sliven. The uprising was brutally crushed by the Ottomans who brought irregular Ottoman troops (bashi-bazouks) from outside the area. Many villages were pillaged and around twelve thousand people were massacred, the majority of them in the insurgent towns of Batak, Perushtitza and Bratzigovo in the area of Plovdiv. The massacres aroused a broad public reaction led by liberal Europeans such as William Ewart Gladstone, who launched a campaign against the "Bulgarian Horrors". The campaign was supported by a number of European intellectuals and public figures, such as Charles Darwin, Oscar Wilde, Victor Hugo and Giuseppe Garibaldi.

Conference of Constantinople

The strongest reaction, however, came from Russia. The enormous public outcry which the April Uprising had caused in Europe gave the Russians a long-waited chance to realise their long-term objectives with regard to the Ottoman Empire. The Russian efforts, which were concentrated on ironing out the differences and contradictions between the Great Powers, eventually led to the Conference of Constantinople held in December 1876 – January 1877 in the Ottoman capital. The conference was attended by delegates from Russia, Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, Germany and Italy and was supposed to bring a peaceful and lasting settlement of the Bulgarian Question.

Russia insisted to the last minute on the inclusion of all Bulgarian-inhabited lands in Macedonia, Moesia, Thrace and Dobrudja in the future Bulgarian state, whereas Britain, afraid that a greater Bulgaria would be a threat to British interests on the Balkans, favoured a smaller Bulgarian principality north of the Balkan Mountains. The delegates eventually gave their consent to a compromise variant, which excluded southern Macedonia and Thrace, and denied Bulgaria access to the Aegean sea, but otherwise incorporated all other regions in the Ottoman Empire inhabited by Bulgarians (illustration, left). At the last minute, however, the Ottomans rejected the plan with the secret support of Britain.

Russo-Turkish War, 1877–1878

Having its reputation at stake, Russia had no other choice but to declare war on the Ottomans in April 1877. The Romanian army and a small contingent of Bulgarian exiles also fought alongside the advancing Russians. The Russians and Romanians were able to inflict a decisive defeat on the Ottomans at the Battle of Shipka Pass and at the Pleven, and, by January 1878 they had occupied much of Bulgaria. They were thus able to dictate terms to the Sultan, and in the Treaty of San Stefano they proposed creating a large Bulgarian state, embracing almost all of the lands populated by Bulgarians. The Sultan was in no position to resist, but the other powers were not willing to allow the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire or the creation of a large Pro-Russian state on the Balkans.

According to Philip Roeder, the Treaty of San Stefano "transformed" Bulgarian nationalism, turning it from a disunited movement into a united one.[4]

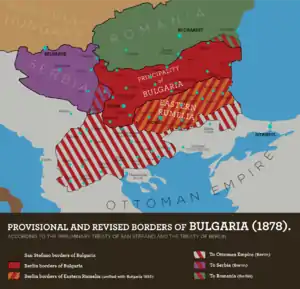

Treaty of Berlin

As a result, the Treaty of Berlin (1878), under the supervision of Otto von Bismarck of Germany and Benjamin Disraeli of Britain, revised the earlier treaty, and scaled back the proposed Bulgarian state. Much of the Bulgarian territories were returned to the Empire (part of Thrace and Macedonia), while others were given to Serbia and Romania.

A Principality of Bulgaria was created, between the Danube and the Stara Planina range, with its seat at the old Bulgarian capital of Veliko Turnovo, and including Sofia. This state was to be under nominal Ottoman sovereignty but was to be ruled by a prince elected by a congress of Bulgarian notables and approved by the Powers. They insisted that the Prince could not be a Russian, but in a compromise Prince Alexander of Battenberg, a nephew of Tsar Alexander II, was chosen.

Between the Stara Planina and the line of the Rhodope Range, which runs about 50 km north of the modern border between Bulgaria and Greece, the autonomous province of Eastern Rumelia was created. With its capital at Plovdiv, it was to be under Ottoman sovereignty but governed by a Christian governor appointed by the Sultan with the approval of the Powers. This hybrid territory was governed by Alexander Bogoridi for most of its brief existence.

See also

References

- ↑ American Contribution to the Revival in Bulgaria

- ↑ From Rum Millet to Greek and Bulgarian Nations: Religious and National Debates in the Borderlands of the Ottoman Empire, 1870–1913, Theodora Dragostinova , Ohio State University, Columbus.

- ↑ A Concise History of Bulgaria, R. J. Crampton, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0521616379, p. 74.

- ↑ Roeder, Philip G. (2007). Where Nation-States Come From: Institutional Change in the Age of Nationalism. Princeton University Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-691-13467-3. JSTOR j.ctt7t07k.