.jpg.webp)

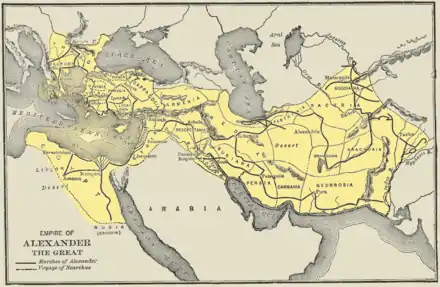

Nearchus or Nearchos (Greek: Νέαρχος; c. 360 – 300 BC) was one of the Greek officers, a navarch, in the army of Alexander the Great. He is known for his celebrated expeditionary voyage starting from the Indus River, through the Persian Gulf and ending at the mouth of the Tigris River following the Indian campaign of Alexander the Great, in 326–324 BC.

Early life

A native of Lato[1] in Crete and son of Androtimus,[2] his family settled at Amphipolis in Macedonia at some point during Philip II's reign (we must assume after Philip took the city in 357 BC), at which point Nearchus was probably a young boy. He was almost certainly older than Alexander, as were Ptolemy, Erigyius, and the others of the ‘boyhood friends’;[3] so depending on when Androtimus came to Macedonia Nearchus was quite possibly born in Crete. Nearchus, along with Ptolemy, Erigyius and Laomedon, and Harpalus, was one of Alexander's ‘mentors’ – and he was exiled by Philip as a result of the Pixodarus affair (A 3.6.5; P 10.3). It is not known where the exiles went, but they were recalled only after Philip's death, on Alexander's accession.

Conquests of Alexander the Great

After their recall, these men were held in the highest honour. Nearchus was appointed as satrap of Lycia and Pamphylia in 334/3 BC (A 3.3.6), one of the earliest of Alexander's satrapal appointments. Nearchus' naval blockade of Persian fleets threatening the Aegean Sea was successful in aiding Alexander's conquest of Phoenicia, Egypt and Babylonia. In 328 BC he was relieved of his post and rejoined Alexander in Bactria (northern Afghanistan), bringing with him reinforcements (A 4.7.2; C 7.10.4, but does not mention Nearchus himself). After the siege of Aornos in present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, Nearchus was sent at the head of a reconnaissance mission – especially to find out about elephants (A 4.30.5–6).

Indus River Voyage

In 326 BC, Nearchus was made admiral of the fleet that Alexander had constructed at the Hydaspes (A 6.2.3; Indica 18.10). However, his trierarchy was a financial responsibility – that is, Nearchus put up the money for the boats (Heckel, p. 229); and there were plenty of other trierarchs in the Indus fleet who were not natural-born sailors. Strabo recounts that the Himalayan range of Emodus was close to the construction of the fleet near Taxila, providing ample supplies of fir, pine and cedar timber.[4] Initially, the fleet progressed down the Hydaspes much like a triumphal military parade, accompanied by a land-based entourage of the main armed forces of Alexander including cavalry, elephants and loot trains. At the confluence of the Acesines and Indus Rivers, Alexander founded a city called Alexandria-on-the-Indus, assigning it to the satrapy of Oxyartes (father of Roxana) and populating it with Thracian troops.

Some of the ships were damaged, and Nearchus was instructed to remain behind to oversee repairs, before continuing down the river. This perhaps indicates some knowledge of shipbuilding, but he could hardly have been the only one qualified. The voyage down the Indus River lasted from 326 to 325 BCE and resulted in the capture of native Indian towns. By the time the Macedonians had reached Pattala (modern Bahmanabad in Sindh, Pakistan), Nearchus prepared to lead 17–20,000 men for an expedition into the Persian Gulf, while Alexander continue through the Gedrosian desert. Nearchus was not the only Greek naval officer to have pursued a voyage down the Indus River—this was also done by Scylax of Caryanda under the commission of Darius the Great, according to Herodotus.

Nearchus remained in command of the fleet for the voyage from the Indus to the Persian Gulf, which he recorded in detail (and which was used extensively for Arrian’s Indica). Again, although he was the admiral, in command of the fleet, great seamanship was not required – the naval responsibilities were Onesicritus’. Nearchus compiled the story of his expedition into a written work—the Indike—which is now lost but informs some of the content in Arrian's Indica and Strabo's Geographica. This work likely consisted of two parts: one detailing India's frontiers, size, population, castes, fauna, flora, cultures and militaries, and the other describing his home-bound voyage toward Babylon. Nearchus described, according to Arrian, how commodities like rice, sugarcane and cotton fabrics and textiles were cultivated, manufactured and traded in the Indus Valley.

Persian Gulf Voyage

Nearchus began by setting out from Patala, although monsoon rains and heavy winds delayed his reaching the Arabian Sea. To wait out the adverse weather, the Macedonian fleet camped near the mouth of the Indus and Arabius Rivers, building stone walls as fortification against hostile natives and subsisting off of briny water, mussels, oysters and razor-fish. After 24 days, Nearchus continued on to the harbor of Morontobara (Manora Island just off the coast of modern Karachi, Pakistan). About Morontobara, Arrian writes:

- Then making their way through two rocks, so close together that the oar-blades of the ships touched the rocks to port and starboard, they moored at Morontobara, after sailing some three hundred stades. The harbour is spacious, circular, deep, and calm, but its entrance is narrow. They called it, in the natives' language, 'The Ladies' Pool,' since a lady was the first sovereign of this district. When they had got safe through the rocks, they met great waves, and the sea running strong; and moreover it seemed very hazardous to sail seaward of the cliffs. For the next day, however, they sailed with an island on their port beam, so as to break the sea, so close indeed to the beach that one would have conjectured that it was a channel cut between the island and the coast. The entire passage was of some seventy stades. On the beach were many thick trees, and the island was wholly covered with shady forest. About dawn, they sailed outside the island, by a narrow and turbulent passage; for the tide was still falling. And when they had sailed some hundred and twenty stades they anchored in the mouth of the river Arabis. There was a fine large harbour by its mouth; but there was no drinking water; for the mouths of the Arabis were mixed with sea-water. However, after penetrating forty stades inland they found a water-hole, and after drawing water thence they returned back again. By the harbour was a high island, desert, and round it one could get oysters and all kinds of fish. Up to this the country of the Arabians extends; they are the last Indians settled in this direction; from here on the territory, of the Oreitans begins.

At Morontobara, Leonnatus (one of Alexander's Generals) had defeated the local Oreitans and deposited a food supply from which Nearchus' fleet subsisted. Resupplied, Nearchus reached the Hingol River (in Makran, Balochistan) and destroyed the native population. Nearchus had arrived at the country of the Icthyophagoi -- 'Fish-Eaters' -- who inhabited the barren coastal region of Makran, between the Arabian Sea and the Gedrosian Desert and found the harbor of Bagisara (modern Ormara Port).

In the next stage of the expedition, Nearchus and his fleet sheltered first at Colta, then Calima (Kalat), Carnine (Astola Island), Cysa and Mosarna. At Mosarna, a Gedrosian sailor joined their fleet and directed them to Gwadar, where they found date-palms and gardens. They ransacked the city of Chah-Bahar and anchored the fleet at a promontory dedicated to the Sun God, called Bageia. Nearchus continued on to the Persian Gulf at the Straits of Hormuz. After many adventures, Nearchus arrived in Carmania in Southern Iran, meeting up with Alexander after the latter's crossing of the Gedrosian desert. Here they noted that the area was well-cultivated with corn (grain), vines and trees (apart from the olive tree cherished by Greeks). At the Straits of Hormuz, Nearchus and Onesicritus saw the peninsula of Oman in Arabia, but did not venture there. Oman was a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire before Alexander's conquest.

During the voyage, Nearchus was reputedly the first Greek commander to visit Bahrain, which was called Tylos by the Greeks. His visit marked the start of Bahrain's inclusion within the Hellenic world, which culminated in the worship of Zeus (as the Arab sun god, Shams) and Greek being spoken as the language of the upper classes. Bahrain even hosted Greek athletic contests. Nearchus recorded that Bahrain was a prosperous commercial island, stating:

"That in the island of Tylos, situated in the Persian Gulf, are large plantations of cotton tree, from which are manufactured clothes called sindones, a very different degrees of value, some being costly, others less expensive. The use of these is not confined to India, but extends to Arabia."

The Macedonians visited many ports in the Persian Gulf such as Harmozeia, Qeshm Island, Cape Ra's-e Bostâneh, Qeys Island, Band-e Nakhîlû, Lâzeh Island (where they encountered pearl-hunters), the Bandar-e Shîû promontory, Nây Band, Kangan, the Mand River, Bûsher, the Dasht-e Palang River, Jazireh-ye Shîf and the Marun River. They finally reached the mouth of the Tigris River in 324 BCE.[5]

After reaching the Tigris River, Nearchus went as far as the Euphrates before turning back to rejoin Alexander at Susa, in early 324 BC. He and Onesicritus received a golden diadem for their actions. Nearchus married the daughter of Barsine and Mentor (A 7.4.6), and received a crown as recognition of his exertions (A 7.5.6). He then took the fleet up to Babylon, where he gave Alexander the Chaldeans’ warning not to enter the city (P 73.1–2).

Later life

Nearchus had a place in Alexander's final plans, as he was to be the admiral of the fleet to conquer Arabia, a land Alexander wished to conquer to fortify trade and transportation in the Persian Gulf between Babylon and India. These plans were cut short by the king's death.

In the initial arguments over the rule of the empire Nearchus supported Heracles, Alexander's son by Barsine – the king's mistress was now his mother-in-law. Once order broke down he joined Antigonus' camp. His last mention is as an adviser to Demetrius in 313/2 BC (D 19.69.1); what happened after that is not known, although he probably retired to write his history. Nearchus wrote a history of his voyages together with a description of India entitled Indica. This text is now lost, but its contents are known from information included by Strabo and other later authors. An account of his voyage is given in Arrian's own Indica, written in the 2nd century AD.[6] Pliny the Elder wrote that Nearchus founded the town of Arbis during his voyage.[7]

Legacy

The hellenic navy named in 1980 a Fletcher class destroyer under the name of the navarch (D-65). Later on in 1992 the Hellenic navy named the second C.F Adams destroyer Nearchus ( D-219). In 27 September 2022 the hellenic navy announced that the second FDI frigate will be named Nearchus as well.

References

- ↑ Who's who in the Age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander's Empire By Waldemar Heckel Page 171 ISBN 1-4051-1210-7

- ↑ "Livius history". Archived from the original on 2015-11-08. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- ↑ Heckel, "Marshals" p.228

- ↑ Vincent, William (1797). The Voyage of Nearchus from the Indus to the Euphrates: Collected from the Original Journal Preserved by Arrian, and Illustrated by Authorities Ancient and Modern ... T. Cadell, jun. and W. Davies. p. 15.

- ↑ "Nearchus - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ↑ "Livius history". Archived from the original on 2015-11-08. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, §6.26.1

Cf.Davaras, Costis. (1989). Νέαρχος ὁ Λάτιος, Amaltheia 20, pp. 233–240.

Ancient authorities: Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri, vi. 19, 21; vii. 4, 19, 20, 25: Plutarch, Life of Alexander, 10, 68, 75: Strabo, xv. pp. 721, 725; Diodorus Siculus, xvii. 104: Justin, xiii. 4.

Further reading

- Badian, E. 1975. 'Nearchus the Cretan', YCIS (24.1), 147-170.

- Sofman, A. S., and D. I. Tsibukidi. 1987. 'Nearchus and Alexander', AncW (16.3-4), 71-77.

- Biagi, P. 2017. 'Uneasy Riders: With Alexander and Nearchus from Pattala to Rhambakia.' In C. Antonetti and P. Biagi (eds.), With Alexander in India and Central Asia: Moving East and Back to West (Oxbow: Oxford), 255-278.

- Bucciantini, V. 2017. 'From the Indus to the Pasitigris: Some Remarks on the Periplus of Nearchus in Arrian's Indike.' In C. Antonetti and P. Biagi (eds.), With Alexander in India and Central Asia: Moving East and Back to West (Oxbow: Oxford), 279-292.

- James, D. 2020. 'Nearchus, Guides, and Place Names on Alexander’s Expedition: Arrian’s Indica 27.1 (FGrH 133 F 1 III)', Mnemosyne (73.4), 553-576.

External links

- Arrian, The Indica translated by E. Iliff Robson.

- Pothos.org:Nearchus by Marcus Pailing

- Livius, Nearchus by Jona Lendering

- The Trierarchs Archived 2016-05-05 at the Wayback Machine of Nearchus by livius.org

- Nearchus the Cretan and the Foundation of Cretopolis

- https://hellasarmy.gr/hn_unit.php?id=D219

- https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2022/09/hellenic-navy-reveals-the-names-of-its-fdi-hn-frigates/