Negoslavci

| |

|---|---|

| Općina Negoslavci Општина Негославци Municipality of Negoslavci | |

Images of Negoslavci | |

Flag  Seal | |

| |

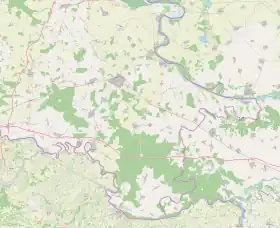

Negoslavci Location of Negoslavci in Croatia  Negoslavci Negoslavci (Croatia)  Negoslavci Negoslavci (Europe) | |

| Coordinates: 45°17′N 19°00′E / 45.28°N 19°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Syrmia (Podunavlje) |

| County | |

| Government | |

| • Municipal mayor | Dušan Jeckov (SDSS[2]) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 21.2 km2 (8.2 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 21.2 km2 (8.2 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)[4] | |

| • Municipality | 983 |

| • Density | 46/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 983 |

| • Urban density | 46/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (Central European Time) |

| Postal code | 32 239 |

| Area code | 32 |

| Vehicle registration | VU |

| Official languages | Croatian, Serbian[5] |

| Website | opcina-negoslavci |

Negoslavci (Serbian Cyrillic: Негославци,[6] Hungarian: Negoszlovce) is a village and a municipality in Vukovar-Syrmia County in eastern Croatia. It is located south of the town of Vukovar, seat of the county. Landscape of the Negoslavci Municipality is marked by the Pannonian Basin plains and agricultural fields of maize, wheat, common sunflower and sugar beet.

The modern day municipality was established in 1997 by the UNTAES administration as one of new predominantly Serb municipalities in order to ensure access to local self-government to Serb community in the region.

Name

Geography

Negoslavci municipality has a total area of 21.21 km2 (8.19 sq mi)[7] and is the smallest member municipality of Joint Council of Municipalities. It is connected by D57 highway with the rest of the country.

History

The village of Negoslavci finds its earliest historical mention in documents from the 15th century. The establishment of the village is most likely associated with the period of Ottoman rule in Hungary, as its presence is not recorded in earlier medieval documents.[8] During the Ottoman era, Negoslavci was designated as "Nigoslavci," and its considerable land holdings extended up to the nearby village of Sotin.[8] The departure of Roman Catholic ethnic Croats from Negoslavci following the Ottoman retreat from Syrmia remains under unspecified circumstances.[8] Subsequently, the village experienced settlement by Eastern Orthodox communities, resulting in 51 households in 1736, all adhering to the Eastern Orthodox faith.[8]

According to local tradition, the settlement's origin traces back to the period of the Great Migrations of the Serbs after the Treaty of Karlowitz, when approximately 15-20 Serbian families seeking refuge from Ottoman territories settled in Negoslavci. During this period, the village was encompassed within the Vukovar Estate and was held by the Kufstein counts until 1736, at which point ownership transitioned to Count Philip of Eltz, the Archbishop-Elector of Mainz. The larger administrative unit, the Vukovar Estate, comprised 31 villages, including Negoslavci.

The village endured a protracted period of limited population growth due to challenging living conditions and disease outbreaks. Notably, it wasn't until the mid-19th century, with the influx of families from the Bačka region, that a noticeable demographic expansion occurred. By 1866, the village's population reached 890, residing in 170 households.[8] Of these inhabitants, 866 were of the Eastern Orthodox faith, while the remainder included Roman Catholic Croats and Germans.[8]

During the Austro-Hungarian administration, Negoslavci served as a municipal center. Throughout this period, significant developments took place, including the construction of a new town hall in 1901, followed by the establishment of a new school building in 1909. In 1912, the integration of the village into the narrow-gauge railway network occurred with the inauguration of the railway line between Vukovar and Ilača, with the railway station positioned approximately one kilometer away from the village.

During the World War II in Yugoslavia and the Genocide of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia Johann Pfeiffer, a member of the local German community from Vukovar, served as the village's administrator.[9] Pfeiffer's active involvement in aiding local Serbs to evade Wehrmacht and Ustashe incarcerations resulted in his family being exempt from the subsequent post-World War II expulsion of Germans from Yugoslavia.[9] In the aftermath of the war, the village experienced resettlement by inhabitants from Bosnia and Herzegovina. The year 1955 was marked by the establishment of the local agricultural cooperative, which paralleled the self-sustained agriculture pursued by a notable segment of the population. Other residents found employment in Vukovar's industrial companies such as Vupik, Vuteks, as well as the Borovo industrial complex.

Demographics

Population

Negoslavci has 1,417 inhabitants, the majority of whom are Serbs, making up 96.86 percent of the population according to the 2011 population census. This makes Negoslavci the municipality with the second-highest percentage of Serbs in Croatia. It is also the municipality with the lowest percentage of Croats (1.78%) in the country.[10]

Languages

Due to the local minority population, the Negoslavci municipality prescribe the use of not only Croatian as the official language, but the Serbian language and Serbian Cyrillic alphabet as well.[11][12]

Religion

The majority of the population belongs to the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Politics

Joint Council of Municipalities

The Municipality of Negoslavci is one of seven Serb majority member municipalities within the Joint Council of Municipalities, inter-municipal sui generis organization of ethnic Serb community in eastern Croatia established on the basis of Erdut Agreement. As Serb community constitute majority of the population of the municipality it is represented by 2 delegated Councillors at the Assembly of the Joint Council of Municipalities, double the number of Councilors to the number from Serb minority municipalities in Eastern Croatia.[13]

Municipal government

The municipality assembly is composed of 11 representatives. Assembly members come from electoral lists winning more than 5% of votes. Dominant party in Negoslavci since the reintegration of eastern Slavonia in 1998 is Independent Democratic Serb Party. 323 or 30,62 % out of 1,055 voters participated in 2017 Croatian local elections with 94,72 % valid votes.[14] With 96,28% and 311 votes Dušan Jeckov from Independent Democratic Serb Party was elected as municipality major.[14] As of 2017, the member parties/lists are:

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Democratic Serb Party | 305 | 100,00 | 11 | ||||

| Invalid/blank votes | 17 | 5,28 | — | ||||

| Total | 322 ballots and 323 voters | 100 | — | ||||

| Registered voters/turnout | 1.055 | 30,52 %/30,62 % | — | ||||

| |||||||

| Source:[14] page 59-60 (in Croatian) | |||||||

Minority councils

Directly elected minority councils and representatives are tasked with consulting tasks for the local or regional authorities in which they are advocating for minority rights and interests, integration into public life and participation in the management of local affairs.[15] At the 2023 Croatian national minorities councils and representatives elections Serbs of Croatia fulfilled legal requirements to elect 10 members minority councils of the Negoslavci Municipality.[16]

Economy

Negoslavci is underdeveloped municipality which is statistically classified as the First Category Area of Special State Concern by the Government of Croatia.[17] According to municipal mayor unemployment is one of the biggest problems of Negoslavci.[18]

Education

The Elementary School in Negoslavci was established in 1761.[19] The new school building was constructed in 1981. Since 1992 school operates as an eight grade school, and due to increased number of students come to upgrade two classrooms with USAID funds.[19] Each year the school celebrates traditional feast slava dedicated to Saint Sava.[20] In 2011, during celebration of 250 anniversary, school issued Chronicle of elementary school in Negoslavci which was jointly funded by Vukovar-Srijem County, Joint Council of Municipalities, Negoslavci municipality, Prosvjeta, Serb National Council and other donors.[21]

Culture

Points of Interest

Church of the Dormition of the Theotokos is a Serbian Orthodox church completed in 1757. There are two ossuaries from the period of World War II with the bones of Yugoslav Partisan fighters from the time of Syrmian Front.[22] First of the ossuaries state in Serbian Cyrillic script "In the glorious name of 40 fighters of the 1st Proletarian and 8th Montenegrin Brigade, the 1st Proletarian Division, who fell in 1944-1945 on the Syrmian Front for the freedom and the better future of their people."[22] On the second one with the unknown number of fighters there is Cyrillic inscription "You who have shed your blood, you who have given your young lives, You who have fall for the sake of freedom, We honor you with the greatest glory and thankfulness. Negoslavci Women's Section."[22]

In popular culture

Negoslavci attracted media attention in Croatia and abroad after its consistent elections patterns, which were different from the predominantly conservative ones in Slavonia. In 2016 Al Jazeera Balkans commentator Borna Sor jokingly compared 'liberal' Negoslavci with the mythological country of Arcadia after conservative Croatian Democratic Union failed to receive a single vote in the municipality (their worst result in the country) despite good results in the rest of the region.[23] At the time of 2013 Croatian constitutional referendum, which created a constitutional prohibition against same-sex marriage, 75% of voters in Negoslavci rejected the proposal, which was the highest percentage of opposition in Croatia.[24] Negoslavci had the lowest turnout at the referendum, with only 3% of voters taking part.[24]

Associations and institutions

Volunteer fire department is active in the village of Negoslavci.[25]

Sport

The football team PZ Negoslavci is situated in this village. Football is the main sport played and possibly the only organized sport in the municipality.

Twin municipalities – Sister municipalities

Other forms of cooperation

See also

References

- ↑ Government of Croatia (October 2013). "Peto izvješće Republike Hrvatske o primjeni Europske povelje o regionalnim ili manjinskim jezicima" (PDF) (in Croatian). Council of Europe. p. 36. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ↑ "Informacija o rezultatima izbora članova predstavničkih tijela jedinica lokalne i područne (regionalne) samouprave" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-13. Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- ↑ Register of spatial units of the State Geodetic Administration of the Republic of Croatia. Wikidata Q119585703.

- ↑ "Population by Age and Sex, by Settlements, 2021 Census". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in 2021. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2022.

- ↑ Četvrto izvješće Republike Hrvatske o primjeni Europske povelje o regionalnim ili manjinskim jezicima, page 61., Zagreb, 2009

- ↑ "Minority names in Croatia:Registar Geografskih Imena Nacionalnih Manjina Republike Hrvatske" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ↑ "Vukovarsko-srijemska županija - Negoslavci". Archived from the original on 2011-10-10. Retrieved 2012-02-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mirko Marković (2003). Istočna Slavonija: Stanovništvo i naselja. Zagreb: Naklada Jesenski i Turk. p. 55. ISBN 9532221239.

- 1 2 Barišić Bogišić, Lidija (2022). O neslavenskom stanovništvu na vukovarskom području. Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada. p. 124. ISBN 978-953-169-497-1.

- ↑ "Population by Ethnicity, by Towns/Municipalities, 2011 Census: County of Vukovar-Sirmium". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- ↑ Izvješće o provođenju ustavnog zakona o pravima nacionalnih manjina i o utošku sredstava osiguranih u državnom proračunu Republike Hrvatske za 2008. godinu za potrebe nacionalnih manjina, Zagreb, 2009.

- ↑ "REGISTAR GEOGRAFSKIH IMENA NACIONALNIH MANJINA REPUBLIKE HRVATSKE" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ↑ "Konstituisan 6. saziv Zajedničkog veća opština l" (in Serbian). Zagreb: Privrednik. 1 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Informacija o izborima članova predstavničkih tijela jedinica lokalne i područne (regionalne) samouprave i općinskih načelnika, gradonačelnika i župana te njihovih zamjenika - 2017 (Vukovarsko-srijemska županija)" (PDF) (in Croatian). Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ↑ "Manjinski izbori prve nedjelje u svibnju, kreću i edukacije". T-portal. 13 March 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ↑ "Informacija o konačnim rezultatima izbora članova vijeća i izbora predstavnika nacionalnih manjina 2023. XVI. VUKOVARSKO-SRIJEMSKA ŽUPANIJA" (PDF) (in Croatian). Državno izborno povjerenstvo Republike Hrvatske. 2023. p. 18. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ↑ Lovrinčević, Željko; Davor, Mikulić; Budak, Jelena (June 2004). "AREAS OF SPECIAL STATE CONCERN IN CROATIA- REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT DIFFERENCES AND THE DEMOGRAPHIC AND EDUCATIONAL CHARACTERISTICS". Ekonomski pregled, Vol.55 No.5-6. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ "Zajedno do novca iz fondova EU-a".

- 1 2 "Osnovna škola Negoslavci - Povijest". Archived from the original on 2011-08-23. Retrieved 2012-02-15.

- ↑ "Osnovna škola Negoslavci - Naslovnica".

- ↑ "Osnovna škola Negoslavci - Naslovnica".

- 1 2 3 "Generalni konzulat Republike Srbije u Vukovaru". Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Serbia). Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ↑ "Negoslavci, čudo od sela u maloj općini Slavonije, utvrđenom selu, okruženom konzervativnim legionarima, stanovnici nisu dali niti jedan glas HDZ-u". Al Jazeera Balkans. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- 1 2 "NAJVEĆE IZNENAĐENJE REFERENDUMA 'ZEZAJU NAS DA SMO SRBI KOJI VOLE PEDERE' Kako su Negoslavci postali najtolerantniji u Hrvatskoj?". Jutarnji list. 8 December 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ↑ "PRILOG 9. POPIS VATROGASNIH POSTROJBI" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-30. Retrieved 2011-10-15.

- 1 2 3 4 "Novosti-Zajedno do novca iz fondova EU-a" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-03-13.