Neil C. Macdonald | |

|---|---|

| |

| 10th North Dakota Superintendent of Public Instruction | |

| In office 1917–1918 | |

| Preceded by | Edwin J. Taylor |

| Succeeded by | Minnie J. Nielson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Neil C. Macdonald March 17, 1876 Canada |

| Died | September 8, 1923 (aged 47) Montana |

| Spouse | Kathrine Belanger |

Neil Carnot Macdonald (March 17, 1876 – September 8, 1923) was an American educator from North Dakota. He served as the tenth North Dakota Superintendent of Public Instruction from 1917 to 1918.

Early life

Neil C. Macdonald was born on March 17, 1876, in Ontario, Canada. His parents were Neil R. and Isabelle (McLeod) Macdonald. The Macdonald family immigrated to the United States in 1885, settling in Cavalier County, Dakota Territory.[1] For many years, the Macdonalds, and their nine children, lived in a sod shanty.[2]

Education and early career

A local school had not yet been organized, so for grade school, Neil had to leave the family farm. He resided and attended school in Langdon. At the age of sixteen, Neil was awarded a North Dakota teaching certificate after completing the county superintendent's teacher's examination, and he began teaching in Cavalier County.[2]

In 1896, Macdonald graduated from Mayville Normal School. He received a bachelor's and master's degree from the University of North Dakota in 1900 and 1908, respectively.[1] While studying at the University of North Dakota, one of his roommates was Lynn Frazier, who would later be elected governor.[2] In the summer of 1903, Macdonald attended the University of Chicago as a graduate student.[2]

Between 1900 and 1911, Macdonald served as superintendent of schools for Cavalier County, superintendent of schools in Lidgerwood, and a similar role in Mandan.[1] Between 1911 and 1916, he worked in various roles for the Department of Public Instruction, including State Inspector of Elementary Schools.[1][3] He spearheaded an initiative to improve educational opportunities for rural students, and he called this "A Square Deal for the Country Boy."[2]

Macdonald's zeal for education earned him national recognition. He received a place in Who's Who in America, and in 1913, he was a keynote speaker at the National Education Association meeting in Salt Lake City.[2]

Superintendent of Public Instruction

In 1915, Superintendent of Public Instruction Edwin J. Taylor announced he would resign at the end of his term. Macdonald announced his candidacy and received the endorsement of the Nonpartisan League (NPL).[2] In recent years, the NPL had risen to prominence in North Dakota with promises of advocating for farmers and challenging "Big Business."[4]

In the election of 1916, Macdonald defeated W. E. Hoover by more than 35,000 votes.[5] Having grown up in rural North Dakota and experienced the hardships of rural education directly, he made rural schools a priority of his administration.[6] He formed workshops called "Better Rural School Rallies," which helped boost schoolchildren attendance.[1] Macdonald recommended schools adopt a calendar that was more supportive of farm life.[2]

In 1918, Macdonald ran for reelection, and he again received the endorsement of the NPL. Macdonald's opponent was Minnie Nielson, an educator and superintendent of schools for Barnes County.[2]

Macdonald and the NPL contested Nielson calling into question her qualifications for the office.[7] Publicly, Macdonald focused on the qualification issue, but in private he was much blunter toward Nielson. In a September 1918 letter, he wrote, "They have a Miss Nielson after me; a dear, fat old maid, who is making a campaign on three issues, namely: One, that she is a woman, second, that she is poorly educated, and therefore anything and everything can teach school if she is elected, third, that she and her friends are against the League, and fourth that she is a Scandinavian; all of which is true except the last one, for it happens that her father and mother were born in Scotland. She is trying to work the nationality racket."[7][1]

Only a few days before the election, Nielson sought the help of William Langer, the NPL-endorsed Attorney General. Nielson asked Langer to review her qualifications and issue an opinion.[8] It was an opportune time, as Langer had been growing dissatisfied with the NPL.[9] On October 29, 1918, Langer issued a statement validating her as a legitimate candidate, having met all of the necessary criteria.[10] This was just the boost Nielson needed. Macdonald lost by more than 5,500 votes.[3][11] With this victory, Nielson was the only candidate to win a statewide position during the 1918 election who was not endorsed by the NPL.[12]

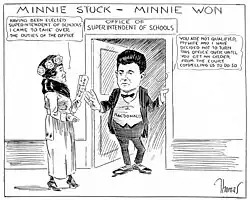

However, Macdonald was not ready to give up. He hung onto the claims that Nielson did not meet the necessary requirements. In early January 1919, Nielson and her staff arrived in Bismarck at the Capitol to move into the office of the Superintendent of Public Instruction. However, Macdonald and his wife Kathrine, who also served as deputy superintendent, refused to leave the office and relinquish their duties.[13][3]

Nielson again turned to Langer, who brought the matter before the North Dakota Supreme Court. A couple of days after the initial confrontation between Macdonald and Nielson, the Supreme Court heard the case and issued their ruling in favor of Nielson.[14]

After the supreme court ruling, the Macdonalds were escorted out of the state superintendent's office by Governor Frazier, along with the sheriff of Burleigh County. Macdonald made one final attempt to maintain control of the office. He demanded Nielson surrender the position to him. Nielson responded with, "I certainly do not intend to do so."[15][8]

Macdonald continued to challenge Nielson's legitimacy in the courts, but with the support of Langer and Assistant Attorney General Edward B. Cox, Nielson was able to keep winning the legal battles.[8][16][17] The vendetta between Macdonald and Nielson seemed unlikely. They both had a lot in common: humble origins, Scottish ancestry, and a passion for education. Political ideology may be their main difference.[7]

However, Macdonald may have also had a personal dislike for Nielson, dating back several years. This was made known when Macdonald and his representation, consisting of Judge John Carmody, Edward S. Allen, state’s attorney of Burleigh County, and J. A. Hyland, had taken the Nielson legitimacy case to district court. Before Macdonald’s action was dismissed by Judge William Nuessle, a 1914 letter was read into the record by Nielson’s counsel, Assistant Attorney General Cox. The letter was written to Macdonald by former state superintendent Edwin J. Taylor. Macdonald, serving as state inspector of rural and graded schools at the time, had previously written to Taylor calling into question Nielson's qualifications for serving as superintendent of schools in Barnes County. Taylor responded, "There are some persons who hold that you are not friendly to Miss Nielson. I entertain the highest regard for Miss Nielson and her ability as an educator, and she has been very loyal to this department."[16]

The campaign season of 1918 was a politically turbulent time for the state of North Dakota. The NPL and the Independent Voters Association (IVA) were battling for political control of the state.[4] The NPL had attacked Nielson for her qualifications, and opponents of the NPL attacked Macdonald for having socialist leanings.[18] Supporters of Macdonald claimed, the "state had replaced a dynamic leader and nationally recognized authority on rural education with a state superintendent who was not even a college graduate and hence could not qualify for the state’s highest teacher’s certificate. It was a misfortune for both the rural schools and the farm boys, whose welfare was so close to Macdonald's heart."[18]

Board of Administration

After losing the election and the Supreme Court case, Macdonald did not go far. Around this same time, the Sixteenth Legislative Assembly convened. At Governor Frazier's recommendation, the NPL-controlled legislature created the Board of Administration.[19][20] This new board replaced the previous Board of Regents and Board of Education, which were abolished, and the board also stripped powers away from the newly elected state superintendent.[20][12] The board consisted of five members: the Commissioner of Agriculture and Labor, the Superintendent of Public Instruction, and three members appointed by the governor.[20]

To some, like the NPL, the creation of the Board of Administration was viewed as a way for the state to increase efficiency and save money by consolidation.[21] However, others viewed the board as a political power grab of the NPL.[22] Upon its creation, a majority of the board, four of the five members, did have ties to the NPL.[23][24][25][26][22]

In September 1919, the Board of Administration appointed Macdonald to serve as educational advisor and general school inspector. The board paid him with a salary equal to Nielson's. However, he did not serve in this role very long, resigning in April 1920.[27][6][3]

Later life

Macdonald left North Dakota an unhappy man. He had been a victim of the NPL-IVA political battle. He soon discovered he was blackballed from teaching.[3] His actions toward Nielson, and his connection with the NPL, caused his reputation to take a hit.[7]

He enrolled at Harvard and completed his Doctor in Education degree. Losing the election of 1918 and resigning from the Board of Administration took its toll on Macdonald's mental health. He had gained weight and began experiencing health problems. Toward the end of his life, he was frequently in and out of hospitals.[3]

To make matters worse for Macdonald, he suffered from a case of mistaken identity when William Howard Taft, former U.S. President, waged a campaign against the NPL in the papers. Taft was a fervent opponent of the NPL.[7][2] Taft reportedly said the NPL was "not a patriotic American party."[28][29] In one article, published in December 1920, in Philadelphia's Public Ledger, Taft confused Macdonald with Charles Emil Stangeland, a one-time consultant of the North Dakota Board of Administration who, in 1919, recommended a number of controversial books for the state library to purchase. Taft accused Macdonald of putting controversial books into the hands of schoolchildren.[7][2] Friends of Macdonald and the NPL came to his aid. Friends flooded Taft with letters denouncing his error.[28] The Nonpartisan Leader, a publication of the NPL, chided Taft in its issue from January 10, 1921. The article stated, "Mr. Taft really ought to get his information about North Dakota from someone with more regard for the truth," and if he continues writing with a careless attention to detail, "Mr. Taft won't bat much better as a political writer than he did as president."[30] Taft later apologized and a retraction was published, but the damage had already been done.[2][7]

Personal life

On June 14, 1904, Macdonald married Kathrine Belanger in Minneapolis. She was the daughter of Ferdinand and Margery (Johnston) Belanger.[2]

In the early 1900s when Neil was employed as the superintendent of Lidgerwood, his wife Kathrine worked as a teacher and principal of the high school.[2] Around 1905, while in Lidgerwood, Neil and Kathrine became surrogate parents of three boys: Kathrine's nephew, Chester Fritz; and Neil's younger brothers, Alex and Donald, who came to live with their brother after the death of their father.[2] Chester Fritz would later become a notable alumnus of the University of North Dakota, and he would have an auditorium and library named after him.

While Neil served as state superintendent, his wife served as deputy superintendent.[31][32] Kathrine was a qualified school administrator, but this appointment was viewed by some as nepotism.[6] Later, after Neil's death, Kathrine married Orrin E. Tiffany.[1][33]

Macdonald was a long-time friend of North Dakota Governor Lynn Frazier.[3]

Neil C.Macdonald was involved with the National Education Association, American Academy of Political and Social Science, Phi Delta Kappa, Shriners, and the Presbyterian Church.[34]

Death

On September 8, 1923, Macdonald died unexpectedly of uremic poisoning in Montana while traveling to accept the role of dean at Seattle Pacific College.[1] He is buried in Hannah Cemetery in Hannah, North Dakota.

In 1926, three years after his death, Neil C. Macdonald was posthumously honored in Bismarck for his work in the North Dakota education system.[2][3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Collections. "Neil C. Macdonald Papers, 1863-1970". University of North Dakota. Archived from the original on 2020-08-13. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Ginger, Janice Lookhart (1986). Neil C. Macdonald, schoolman. North Dakota mini-biography series. Bismarck, ND: State Historical Society of North Dakota. pp. 5–38. OCLC 13766446.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Langermo, Cathy A. (2006-12-29). "Neil C. Macdonald". Prairie Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on 2022-11-08. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- 1 2 State Historical Society of North Dakota. "Nonpartisan League - Summary of North Dakota History". www.history.nd.gov. Archived from the original on 2022-09-02. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ↑ North Dakota Secretary of State (1916). "Party Votes, General Election, November 7, 1916" (PDF). North Dakota Secretary of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-10-18. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- 1 2 3 Myrdal, Mark Kristian (2017). "Laying Aside Vanities: Neil C. Macdonald and the Nonpartisan League". Liberty University. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 McMillan, Jim (1985). "The Macdonald-Nielson Imbroglio: The Politics of Education in North Dakota, 1918-1921". North Dakota History. 52 (4): 2–11. ISSN 0029-2710. OCLC 6781857.

- 1 2 3 Wefald, Susan (2014). Important voices : North Dakota's women elected state officials share their stories, 1893-2013. Fargo, ND: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies Press. pp. 211–234. ISBN 978-0-911042-79-5. OCLC 900649209.

- ↑ North Dakota Studies. "Section 3: William Langer". North Dakota Studies. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ↑ Langer, William (1920). The Nonpartisan League: Its Birth, Activities and Leaders. Morton County farmers Press. pp. 197–198.

- ↑ North Dakota Secretary of State (1918). "Party Votes, General Election, November 5, 1918" (PDF). North Dakota Secretary of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-10-18. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- 1 2 Thomas, Lucid (2015-10-29). "Not Very Minnie". Prairie Public Broadcasting. Archived from the original on 2022-10-28. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ↑ Chronicling America (1919-01-06). "Incumbents in State Job are Loath to Quit". The Bismarck tribune. p. 1. ISSN 2330-5967. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ↑ Chronicling America (1919-01-10). "Macs Ousted; Neilson Wins; Truth Triumphs". The Bismarck tribune. p. 1. ISSN 2330-5967. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ↑ Paulson, H. D. (1919-01-11). "'My business is education, not politics', says Miss M. Nielson". Fargo Forum and Daily Republican. pp. 1, 5. Retrieved 2023-08-31.

- 1 2 Chronicling America (1919-05-21). "Macdonald again loses out in attempt to oust Miss Nielson". The Devils Lake world and inter-ocean. pp. 1, 4. Retrieved 2022-11-21.

- ↑ Chronicling America (1919-10-10). "Supreme Court finds against N. C. Macdonald". The Bismarck tribune. p. 1. ISSN 2330-5967. Retrieved 2023-07-28.

- 1 2 Robinson, Elwyn B. (1966). "History of North Dakota". Open Educational Resources. Chester Fritz Library: 302. doi:10.31356/oers001.

- ↑ "Message of Governor Lynn J. Frazier delivered to the Sixteenth Legislative Assembly of the State of North Dakota, January 8, 1919". Digital Horizons. 1919-01-08. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- 1 2 3 16th Legislative Assembly of North Dakota (1919). "1919 Session Laws: Boards of Administration (Chapter 71)" (PDF). North Dakota Legislative Council. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Chronicling America (1919-07-14). "Decks cleared for farmers' program: administration bill consolidates boards". The nonpartisan leader. p. 5. ISSN 2469-3529. Retrieved 2023-08-04.

- 1 2 Remele, Larry (1977). "The North Dakota State Library Scandal of 1919". North Dakota History. 44 (1): 21–29. ISSN 0029-2710. OCLC 6781857.

- ↑ Eriksmoen, Curt (2011-02-27). "Political battle heated up 1920s Bowman, ND". InForum. Archived from the original on 2022-10-31. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ↑ Chronicling America (1917-12-03). "Regents tangle climax likely in session at Forks Tuesday". The Fargo forum and daily republican. p. 1. ISSN 2688-9447. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ↑ Tittemore, James N.; Vissers, Aloysius Anthony (1922). The Non-partisan League vs. the home. The Library of Congress. [Milwaukee, Burdick-Allen Co., printers]. p. 36.

- ↑ Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Collections. "John N. Hagan Papers, 1897-1960". University of North Dakota. Archived from the original on 2022-10-31. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ↑ North Dakota Board of Administration (1919). Annual report. Bismarck.: North Dakota. p. 49.

- 1 2 Vivian, James F. (1983). "'Not a Patriotic American Party': William Howard Taft's Campaign against the Nonpartisan League, 1920-1921". North Dakota History. 50 (4): 4–10. ISSN 0029-2710. OCLC 6781857.

- ↑ "The Chief Justice - A Mistaken Appointment". The Nation. 113 (2923): 32. 1921-07-13.

- ↑ Chronicling America (1921-01-10). "Mr. Taft Is Learning - But Slowly". The Nonpartisan Leader. p. 4. ISSN 2469-3529. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ↑ Chronicling America (1917-02-01). "Notes from the county superintendent". Emmons County record. p. 1. ISSN 2475-9783. Retrieved 2023-09-01.

- ↑ Chronicling America (1917-07-27). "Who's who in North Dakota officialdom". The Bismarck tribune. p. 2. ISSN 2330-5967. Retrieved 2023-09-01.

- ↑ Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Collections. "Kathrine Tiffany Papers, 1957-1972, 1978, 1988". University of North Dakota. Archived from the original on 2020-08-13. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ↑ North Dakota (1932). "Twenty-second biennial report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction". Biennial Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction. 1888/90-1918/20: Public document: 49–50.