Nelbia Romero | |

|---|---|

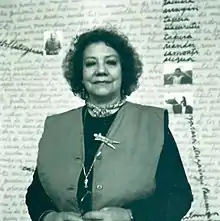

Romero at her show Más allá de las palabras, 1992 | |

| Born | Nelbia Romero Cabrera 8 December 1938 Durazno, Uruguay |

| Died | 3 April 2015 (aged 76) Montevideo, Uruguay |

| Occupation | Artist |

| Notable work | Sal-Si- Puedes, Bye Bye Yaugurú, Más allá de las palabras |

| Parents |

|

| Awards | Figari Award (2006) |

Nelbia Romero Cabrera (8 December 1938 – 3 April 2015) was a Uruguayan visual artist. She began her career in drawing and engraving and later incorporated other artistic languages, such as photography, installation, and performance. Her work was marked by themes of politics and protest.[1] She was an active participant in the Montevideo Engraving Club. She received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1994 and was granted the Figari Award in 2006 for her artistic career.

Biography

Childhood

Nelbia Romero was born on 8 December 1938 in the town of Durazno, Uruguay. She was the eldest daughter of a family of rural landowners. Her parents, Apolinaria Cabrera and Conrado Romero, settled in the city for her birth, where later the youngest daughter of the marriage and her only sister, María Teresa, was born.

Romero's upbringing alternated between the city and the countryside, where she spent her vacations. Her father, a landowner and local political figure, socially active and atheist, shared with his eldest daughter an interest in music and history, passing along his concern for social justice.[2]

Training

Romero completed elementary school and secondary studies at the school of the Immaculate Conception of Durazno. She left without finishing her preparatory architecture studies in 1959 to enter the Durazno Workshop of Plastic Arts. Claudio Silveira Silva, her teacher for two years, strongly influenced her vocation and encouraged her to move to Montevideo to continue her studies at the National Institute of Fine Arts (ENBA). Supported by her father, she moved to the country's capital in 1962, abandoning marriage plans.[2] At the ENBA she received multiple artistic and political influences. The painter Mario Pareja guided her to the graphic arts, suggesting that she enter the printing workshop. In 1967 her father died and she stopped attending the Institute.

In 1968 Romero entered the school of the Engraving Club, where she was a student of Carlos Fossatti and met her former ENBA classmate, Rimer Cardillo. She also participated in the graphic activity of the Club: monthly newsletters, almanacs, and illustrations. In this time she experimented with different materials and studied the history of art at the Faculty of Humanities.

She also received training as an educator of plastic expression, which allowed her to later work as a teacher in primary schools and workshops for adults.

Political activity

Romero was a politically engaged artist who supported causes and social movements through her artistic activity.[1] In 1969 she joined the Communist Party, where she would continue to work until the 1990s.

Artistic production

Early works

During the first phase of Romero's career she was mainly engaged in drawing and engraving. Between 1975 and 1980 she participated in "El Dibujazo", a movement in which draughtsmen and graphic artists took part in expressing themselves against the social conflict of the period of the dictatorship. At this stage she began to show her work in collective exhibitions, and in 1976 she held her first individual exhibition, received some prizes, and sent works abroad. During that year, she collaborated with draftswomen Beatriz Battoine, Irene Ferrando, and Marta Restuccia, and experimented by complementing her samples with audiovisual recordings with Nelson Advalov, which would lead her to new multimedia aesthetic searches in the 1980s.[2][3] In fact, at the end of the decade, in 1988, she retired from the Engraving Club after promoting an unsuccessful attempt at renewal with Ana Tiscornia.[4]

Second stage

Romero's work took a new direction in the 1980s with the incorporation of audiovisual language and the use of her body as a plastic element. In turn, her work was increasingly committed to the personal and social consequences of the recent past. In an interview with Olga Larnaudie, she said:

In the 80s I started with other types of searches linked not only to the formal problem, but to other things that mattered to me. Before the dictatorship, it existed as a privilege to elaborate in the artistic field. That privilege stopped being the first thing, and I felt responsible for my work. The dictatorship also gave us to reset and rethink our proposals. The need to arise with the pain I felt began to appear truly – through my face – looking for who I was in that historical moment. The faces appear half covered, half veiled, painting my face, also in black and white. It was something very profound, very meaningful. The way to say "here I am".[2]

During those years of transition Romero made engravings in which photographs of her inked face appear, which she also printed on the works. With these works she participated in collective exhibitions that expressed the new paths taken by the nation's plastic arts towards the end of the dictatorship and during the first years of the return of democracy. In 1981 she participated in the show paying tribute to Carlos Fossatti exhibited in the Montevideo Gallery of Notaries, with the participation of artists of the Engraving Club, and in 1983 she was part of the Muestra por las libertades organized by the Culture Commission of the Uruguay Banking Association (AEBU) together with more than 300 national and international artists. In 1986 the engravings of this cycle were sent to the Second Havana Biennial as part of the installation A propósito de aquellos años oscuros.[2]

In 1983 she presented Sal-si-puedes ("Get out if you can"), considered the first artistic installation made in Uruguay,[2] which included texts, music, body language, plastic art, and atmosphere. After the fall of the Uruguayan Dictatorship in 1985, she returned to the country and continued work expressing the pre-Hispanic, indigenous heritage of Uruguay through performance, installations, and multimedia work.[5]

The work evokes the Charrúa ethnic group and recalls the Slaughter of the Salsipuedes,[1] constituting a reflection on national identity and pluriculturalism in a country that was considered practically without indigenous heritage.[3] Sal-si-puedes is part of the crisis period of the post-dictatorship era in which the perception of a country with European roots, socially homogeneous and of tolerant tradition, was questioned. Romero was nourished by the artistic and academic production (history, sociology, anthropology) that in this period questioned the historical construction of national identity.[5]

She continued working in the same direction by producing a performance, Uru-gua-y, in 1990, followed by two installations in 1992; Más allá de las palabras ("Beyond words") and Garra Charrúa, which uses, among a heterogeneity of elements, large amounts of text written in Spanish and Guarani, rescuing the linguistic heritage of that nation, present in everyday speech today.[3] This work was presented in Montevideo, in Havana, and at the Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst (Germany).

In Bye Bye Yaugurú, a 1995 installation presented at the Subte Exhibition Center in Montevideo, Romero continued to work on the issue of national identity from a critical perspective. The central element of the work is a map of Uruguay represented in various ways in combination with other elements. It questions the "scientific" reading of the reality that cartography tries to show, highlighting the arbitrariness of the historical tracing of the borders that underpin nationalism.[1]

In the following years she continued to develop her work in installations and performances, at the same time that she intensified her teaching and curatorial activity. In the 2000s she exhibited several times at the national and international level, sending her work to the Havana Biennial and to the Mercosur Biennial.

Romero was also the author of texts, presentations, and talks on printmaking and on topics related to Uruguayan identity.[1]

Awards and recognitions

In 1994 Romero received a Guggenheim Fellowship, and in 2009 the Parliament granted her a gracious pension for being considered a prominent figure in Uruguayan art. In 2005 she received the Figari Award granted by the Central Bank of Uruguay.

Works

- 1983, Sal-si-puedes (installation)

- 1992, Más allá de las palabras (installation)

- 1992, Garra Charrúa (installation)

- 1994, Homenaje a la mujer indígena (performance)

- 1994, Materias pendientes I, II, and III (installation)

- 1995, Bye, bye, Yaugurú (installation)

- 1998, De la vaca inexistente del escudo, a su mesa (performance)

- 2003, Lunfardeces (sonic installation)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Haber, Alicia (16 April 2015). "Nelbia Romero y sus expresiones artísticas" [Nelbia Romero and Her Artistic Expressions]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nelbia Romero (in Spanish). Central Bank of Uruguay. 2006.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 Fajardo-Hill, Cecilia; Giunta, Andrea; Alonso, Rodrigo (2017). Radical women: Latin American art, 1960–1985. Los Angeles: Hammer Museum and DelMonico Books/Prestel. ISBN 9783791356808. OCLC 982089637.

- ↑ Peluffo Linari, Gabriel (June 2011). "Club de grabado en la crisis de la 'cultura independiente' (1973–1989)" [Engraving Club in the Crisis of the 'Independent Culture' (1973–1989)] (PDF). La Pupila (in Spanish). No. 18. pp. 8–17. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- 1 2 Haber, Alicia (1994). "Mitologías de ausencia en el arte uruguayo de hoy: las instalaciones de Rimer Cardillo y Nelbia Romero" [Mythologies of Absence in Uruguayan Art Today: The Installations of Rimer Cardillo and Nelbia Romero]. In Bulhões, Maria Amélia; Bastos Kern, Maria Lúcia (eds.). Artes plásticas na América Latina contemporânea [Visual Arts in Contemporary Latin America] (in Spanish). UFRGS. p. 151. ISBN 9788570253132. Retrieved 9 December 2017 – via Google Books.