Nettie George Speedy (née George; November 3, 1878 – July 7, 1957) was an American journalist and golfer. She worked for the Chicago Defender and The Metropolitan post. Speedy was the first Black woman to play golf in Chicago and among the first to play anywhere in the United States.[1] She founded the Chicago Women's Golf Club, and the first woman to sit on the trustee board of Lane College in Jackson, Tennessee.

Early life and education

The daughter of Mr. Hubbard and Mrs. Ruth Wills George, Nettie George Speedy,[2] arrived in Chicago in a convoluted manner. Her father moved the family from Winchester, Kentucky, to Springfield, Ohio, in 1879, and her mother passed away in 1883.[3] Her father remarried Dora Wade in May 1886 and died six months later. Nettie returned to Winchester, Kentucky, following the deaths of her parents, before migrating to Kansas with her sister Nora in 1895 and enrolling at Parsons High School.[4] By 1900, she had returned to Winchester, Kentucky, where she taught school.[5] Nettie relocated from Kentucky to Chicago to live with her prominent brother, Frank P. George.[6]

She married Walter Speedy Sr., a tailor with a passion for golf. They are both pioneers of African American golf.[7]

Career

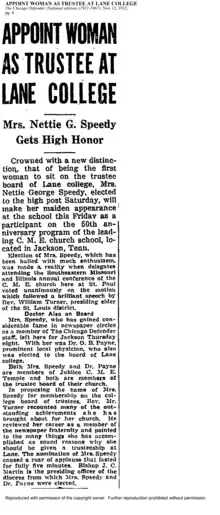

She is a well-known journalist with the Chicago Defender. She wrote on courts, crime, theater, and sports and advocated for African Americans, particularly African American women. Nettie Speedy was the 1st woman to become a trustee at Lane College in Tennessee.[8] According to "The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921–1967); November 12, 1932; page 4," Mrs. Speedy, who has earned notoriety in newspaper circles as a member of the Chicago Defender staff, became the first woman to serve on the board of trustees at Lane College.[9]

Three months later, in January 1916, the Chicago Defender published the first article about an African-American female golfer. In the thick of the social news, readers heard that Walter and Nettie Speedy, two of the city's top golfers, were busy competing in ice skating tournaments at Lincoln and Jackson Parks, demonstrating that they skated just as well as they played golf. One year later, in September, the newspaper reported that a group of four women played golf at Marquette Park. Katherine Kent, a student of Nettie Speedy's from Birmingham, Alabama, achieved the second-lowest score.[10]

Speedy thought golf was a game for men, women, and people from all walks of life, even though at the time, only a small number of African Americans were middle-class. In April 1918, Speedy wrote a lively editorial in which she urged women to learn how to play golf. This showed how much she liked the game. Speedy wrote, "Since the weather conditions are becoming ideal, I am going to ask more of our women to take up golf as their summer pastime." Speedy said that her reason to play golf is because it's good for the health and can be enjoyed by people of all ages, sizes, and genders." "Golf is a game that can be played by people of all ages, sizes, and genders," she added.[11]

In the summer of 1918, Walter Speedy, Robert Ball, and Henry B. Johnson entered the city championship with success. "For the first time in history, men of our Race are competing in a golf championship here, and Walter Speedy and Robert Ball are holding their own with the best of them," Speedy wrote in " The Sidelights." Nettie Speedy recalled in an editorial two weeks later, "We of the golfing world were happy." We were shaking each other’s hands and otherwise manifesting signs of joy.” The next morning, however, the mainstream white press failed to mention either Speedy or Ball among the sixty white golfers who were also entered in the tournament, putting an end to the excitement surrounding the participation of two African Americans in the city's golf tournament. Johnson was eliminated from competition due to an off day, but Speedy and Ball "were still holding their own and have a large fan base." Mrs. Speedy, appalled by the lack of recognition, went to the golf course and questioned one of the promoters about the absence of the two black players. The following morning, the names of Speedy and Ball, the two "Race" players, appeared in every newspaper alongside a warning that they were formidable contenders for the golf championship. In addition, a large number of spectators followed the actors throughout their performance. At one of the tees, in response to Speedy and Ball's incredibly long drives, a man in close proximity to Mrs. Speedy asked his friend, "What do you think of those two shines?" Mrs. Speedy, pretending to misunderstand his meaning, responded, "They are certainly shining, one with the illuminating rays of the sun and the other with the moon in all its glory."[12]

According to the Chicago defender, Nettie Speedy also entertained the candidates for initiation into Sinai Tabernacle No. 81 together with the high priestess, as the honored guest.[13]

In the 1920s, journalist Nettie George Speedy promoted African American involvement in the game and opened local Chicago tournaments to the finest players, regardless of race.[14] As racial discrimination has been an issue in their country that those who are African American golfers are deprived to enjoy the same freedom as the white.

According to Speedy's column from August 5, 1922, the three golfers who qualified for the competition were Robert Ball, Walter Speedy, and Henry B. Johnson. She concluded that Georgia prejudice and Illinois diplomacy conspired to prevent Race men from competing in the tournament because "in 1918, no attention was paid to them, but when Robert Ball played in the semifinals and there was a possibility that a Race man would be wearing the city's golf crown, someone began to get busy."[15]

Due to her great writing as a journalist, she was allowed to attend events throughout the city. Nettie George Speedy was referred to as the "Dean of Women Journalists" at the 1926 banquet honoring the Chicago Press Club, where she was the only woman among the eminent newspapermen who sat on the board.[16]

Speedy, after 14 years of active involvement with the Chicago Defenders, temporarily retired from her newspaper position in 1927, per the advice of her physician, with the intention of returning to work when her health improved.[17]

She founded the Xenias in 1929 with the motto "Fine Womanhood."[18] This club's purpose was to aid women and young girls in making career decisions by sharing her knowledge of newspaper work, and only twelve women and girl were (girls) permitted to join. Nettie was a feminist, and her writings concentrated on the coverage of women. In 1925, she launched the section "Scrapbook of Doers," which celebrated the accomplishments of women.[19] A second column titled "Woman's Page" followed.

According to the article in the Chicago Defender, The Pioneer Club formerly known as (Windy City Golf Association) organized an elaborate social program for the week, what jumped out was the inclusion of a women’s amateur championship to the UGA competition. The presence of Nettie George Speedy on the Pioneer Club Board of Directors impacted the direction of the 1930 organizing committee.[20]

She was involved in the community of Chicago and funded the Cynco Athletic Club in 1933, which was highlighted in Chicago's newest African American newspaper, "The Spokesman[21]."[22]

Speedy wrote in her weekly "Society "column that, "Everyone– socially interested or not– should go out and learn golf, and brush up on golf terms and phrases, for the national golf tournament is just around the corner and promises to be the gala event, starting off the fall season...Famous golfers from all parts of the country are expected here with bags and clubs." She joyfully announced that “All Chicago has gone golf mad” in characterizing the excitement for future events, stating that store displays exhibited mannequins with “alluring sport outfits” and that many tourists passing Chicago planned to stop to watch the national golf competition.[23]

Nettie and Walter Speedy founded the Chicago Women's Golf Club[24]in 1937 in order to promote golf among African American women in Chicago by sponsoring events and cultivating young players. The organization grew and became the premier Black women's social organization in the city. In 1956, the Chicago Women's Golf Club was admitted as a USGA Member Club and granted permission to compete in the USGA Championship.[25]

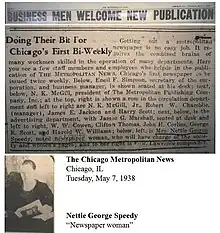

In 1938, she became a journalist for "The Metropolitan Post[26]," a new African American newspaper launched in Chicago in 1938.[27]"Women and Their Activities" was the title of her column. [28]

Death and legacy

Nettie passed away on July 7, 1957, in Hardin County, Ohio, and was laid to rest in the same cemetery as her parents, Ferncliff Cemetery, in Springfield, Ohio. Nettie's parents also rest there.

Due to her many years as a writer, her fight for the rights of African-Americans and women, and her promotion of golf, she introduced the game to a large number of people. Mentoring African Americans in and around Chicago was by far the most significant thing she did in her lifetime, and it remains one of her most remarkable achievements.

References

- ↑ Demas, Lane (2017-08-09). Game of Privilege: An African American History of Golf. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-1-4696-3423-4.

- ↑ "George [Speedy], Nettie · Notable Kentucky African Americans Database". nkaa.uky.edu. Retrieved 2022-12-14.

- ↑ "Sign up". www.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ↑ "The Parsons weekly blade (newspaper) · Notable Kentucky African Americans Database". nkaa.uky.edu. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ↑ United States Census, 1900; https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S3HT-69PQ-VPC?cc=1325221&wc=9BQT-4W5%3A1030552701%2C1030694601%2C1031805001

- ↑ "George, Frank Pendleton · Notable Kentucky African Americans Database". nkaa.uky.edu. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ↑ Past, Present, and Future: The Direction of African American Golf

- ↑ African American Golf History Archive (usga.org)

- ↑ "The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967); November 12, 1932; page 4

- ↑ The Chicago Defender- January 2022, 1916, p.3

- ↑ The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1905-1966); April 27, 1918; pg. 12

- ↑ The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1905-1906); August 31, 1918; p.9

- ↑ The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1905-1966);July 20, 1918, Pg.8

- ↑ "Prejudice and Diplomacy work ill to golfers". The Chicago Defender, N. S.,1922

- ↑ Levin, Jacob (February 12,2021). "Nettie Speedy: Female Journalist, Founder of Chicago Women's G.C."

- ↑ The Officers of the Marching Club of Fort Dearborn Lodge of the Elks...," Broad Axe, 02/13/1926, front page

- ↑ The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967); June 18,1927; Pg.8

- ↑ "Ida B. Wells-Barnett and American reform, 1880-1930 · Notable Kentucky African Americans Database". nkaa.uky.edu. Retrieved 2022-12-12.

- ↑ The Chicago Defender (National Edition); May 23, 1925

- ↑ The Chicago Defender, February 15, 1930; p.9

- ↑ The Spokesman (newspaper) · Notable Kentucky African Americans Database (uky.edu)

- ↑ Cynco Club's Program" Spokesman, 02/04/1933, p.5

- ↑ The Chicago Defender, August 23, 1930, p.7

- ↑ "The Chicago Women's Golf Club". CW GOLF CLUB (CWGC). Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ↑ Nettie Speedy: Female Journalist, Founder of Chicago Women’s G.C. (usga.org), J.L. 02/12/21

- ↑ “The Metropolitian post (newspaper),” Notable Kentucky African Americans Database, accessed December 12, 2022, https://nkaa.uky.edu/nkaa/items/show/300003605.

- ↑ Metropolitan Post, 12/03/1938, p.4

- ↑ Metropolitan Post, 12/03/1938, p.4]