| Nez Perce War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

Chiefs Joseph, Looking Glass, and White Bird in the spring of 1877 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Nez Percé Palouse | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Chief Joseph Looking Glass† White Bird Ollokot† Toohoolhoolzote† Poker Joe† (Lean Elk) Red Echo (Hahtalekin) Bald head (Husishusis Kute) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,500 soldiers, civilian volunteers, Indian scouts | 250 warriors, +500 non-combatant women and children—numbers are approximate | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 125 killed, 146 wounded[1] |

103–133 combatants and noncombatants killed, 71–91 combatants and noncombatants wounded (possibly more)[1] 418 surrendered, 150–200 escaped to Canada[2] | ||||||

The Nez Perce War was an armed conflict in 1877 in the Western United States that pitted several bands of the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans and their allies, a small band of the Palouse tribe led by Red Echo (Hahtalekin) and Bald Head (Husishusis Kute), against the United States Army. Fought between June and October, the conflict stemmed from the refusal of several bands of the Nez Perce, dubbed "non-treaty Indians," to give up their ancestral lands in the Pacific Northwest and move to an Indian reservation in Idaho Territory. This forced removal was in violation of the 1855 Treaty of Walla Walla, which granted the tribe 7.5 million acres of their ancestral lands and the right to hunt and fish on lands ceded to the U.S. government.

After the first armed engagements in June, the Nez Perce embarked on an arduous trek north initially to seek help with the Crow tribe. After the Crows' refusal of aid, they sought sanctuary with the Lakota led by Sitting Bull, who had fled to Canada in May 1877 to avoid capture following the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn.

The Nez Perce were pursued by elements of the U.S. Army with whom they fought a series of battles and skirmishes on a fighting retreat of 1,170 miles (1,880 km). The war ended after a final five-day battle fought alongside Snake Creek at the base of Montana's Bears Paw Mountains only 40 miles (64 km) from the Canada–US border. A large majority of the surviving Nez Perce represented by Chief Joseph of the Wallowa band of Nez Perce, surrendered to Brigadier Generals Oliver Otis Howard and Nelson A. Miles.[3] White Bird, of the Lamátta band of Nez Perce, managed to elude the Army after the battle and escape with an undetermined number of his band to Sitting Bull's camp in Canada. The 418 Nez Perce who surrendered, including women and children, were taken prisoner and sent by train to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Although Chief Joseph is the most well known of the Nez Perce leaders, he was not the sole overall leader. The Nez Perce were led by a coalition of several leaders from the different bands who comprised the "non-treaty" Nez Perce, including the Wallowa Ollokot, White Bird of the Lamátta band, Toohoolhoolzote of the Pikunin band, and Looking Glass of the Alpowai band. Brigadier General Howard was head of the U.S. Army's Department of the Columbia, which was tasked with forcing the Nez Perce onto the reservation and whose jurisdiction was extended by General William Tecumseh Sherman to allow Howard's pursuit. It was at the final surrender of the Nez Perce when Chief Joseph gave his famous "I Will Fight No More Forever" speech, which was translated by the interpreter Arthur Chapman.

An 1877 New York Times editorial discussing the conflict stated, "On our part, the war was in its origin and motive nothing short of a gigantic blunder and a crime".[4][5]

Background

We took away their country and their means of support, broke up their mode of living, their habits of life, introduced disease and decay among them and it was for this and against this they made war. Could anyone expect less?

— Gen. Philip H. Sheridan

In 1855, at the Walla Walla Council, the Nez Perce were coerced by the federal government into giving up their ancestral lands and moving to the Umatilla Reservation in Oregon Territory with the Walla Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla tribes.[6] The tribes involved were so bitterly opposed to the terms of the plan that Isaac I. Stevens, governor and superintendent of Indian affairs for the Washington Territory, and Joel Palmer, superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon Territory, signed the Nez Perce Treaty in 1855, which granted the Nez Perce the right to remain in a large portion of their own lands in Idaho, Washington, and Oregon territories, in exchange for relinquishing almost 5.5 million acres of their approximately 13 million acre homeland to the U.S. government for a nominal sum, with the caveat that they be able to hunt, fish. and pasture their horses etc. on unoccupied areas of their former land – the same rights to use public lands as Anglo-American citizens of the territories.[7]

The newly established Nez Perce Indian reservation was 7,500,000 acres (30,000 km2) in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington territories. Under the terms of the treaty, no white settlers were allowed on the reservation without the permission of the Nez Perce. However, in 1860 gold was discovered near present-day Pierce, Idaho, and 5,000 gold-seekers rushed onto the reservation, illegally founding the downstream city of Lewiston as a supply depot on Nez Perce land.[8] Ranchers and farmers followed the miners, and the U.S. government failed to keep settlers out of Indian lands. The Nez Perce were incensed at the failure of the U.S. government to uphold the treaties, and at settlers who squatted on their land and plowed up their camas prairies, which they depended on for subsistence.[9][10]

In 1863, a group of Nez Perce were coerced into signing away 90% of their reservation to the U.S., leaving only 750,000 acres (3,000 km2) in Idaho Territory.[11] Under the terms of the treaty, all Nez Perce were to move onto the new and much smaller reservation east of Lewiston. A large number of Nez Perce, however, did not accept the validity of the treaty, refused to move to the reservation, and remained on their traditional lands.[12][13][14] The Nez Perce who approved the treaty were mostly Christian; the opponents mostly followed the traditional religion. The "non-treaty" Nez Perce included the band of Chief Joseph, who lived in the Wallowa valley in northeastern Oregon. Disputes there with white farmers and ranchers led to the murders of several Nez Perce, and the murderers were never prosecuted.[15]

Tensions between Nez Perce and white settlers rose in 1876 and 1877. General Oliver Otis Howard called a council in May 1877 and ordered the non-treaty bands to move to the reservation, setting an impossible deadline of 30 days.[16][17] Howard humiliated the Nez Perce by jailing their old leader, Toohoolhoolzote, who spoke against moving to the reservation.[18] The other Nez Perce leaders, including Chief Joseph, considered military resistance to be futile; they agreed to the move and reported as ordered to Fort Lapwai, Idaho Territory.[19] By June 14, 1877, about 600 Nez Perce from Joseph's and White Bird's bands had gathered on the Camas Prairie, six miles (10 km) west of present-day Grangeville.[20]

On June 13, shortly before the deadline for removing onto the reservation, White Bird's band held a tel-lik-leen ceremony at the Tolo Lake camp in which the warriors paraded on horseback in a circular movement around the village while individually boasting of their battle prowess and war deeds. According to Nez Perce accounts, an aged warrior named Hahkauts Ilpilp (Red Grizzly Bear) challenged the presence in the ceremony of several young participants whose relatives' deaths at the hands of whites had gone unavenged. One named Wahlitits (Shore Crossing) was the son of Eagle Robe, who had been shot to death by Lawrence Ott three years earlier. Thus humiliated and apparently fortified with liquor, Shore Crossing and two of his cousins, Sarpsisilpilp (Red Moccasin Top) and Wetyemtmas Wahyakt (Swan Necklace), set out for the Salmon River settlements on a mission of revenge. On the following evening, June 14, 1877, Swan Necklace returned to the lake to announce that the trio had killed four white men and wounded another man. Inspired by the war furor, approximately sixteen more young men rode off to join Shore Crossing in raiding the settlements.[21]

Joseph and his brother Ollokot were away from the camp during the raids on June 14 and 15. When they arrived at the camp the next day, most of the Nez Perce had departed for a campsite on White Bird Creek to await the response of General Howard. Joseph considered an appeal for peace to the Whites, but realized it would be useless after the raids. Meanwhile, Howard mobilized his military force and sent out 130 men, including 13 friendly Nez Perce scouts, under the command of Captain David Perry to punish the Nez Perce and force them onto the reservation. Howard anticipated that his soldiers "will make short work of it."[22] The Nez Perce defeated Perry at the Battle of White Bird Canyon and began their long flight eastward to escape from the U.S. soldiers.

War

Joseph and White Bird were joined by Looking Glass's band and, after several battles and skirmishes in Idaho during the next month,[20] approximately 250 Nez Perce warriors, and 500 women and children, along with more than 2000 head of horses and other livestock, began a remarkable fighting retreat. They crossed from Idaho over Lolo Pass into Montana Territory, traveling southeast, dipping into Yellowstone National Park and then back north into Montana,[17][23] roughly 1,170 miles (1,880 km).[19] They attempted to seek refuge with the Crow Nation, but, rejected by the Crow, ultimately decided to try to reach safety in Canada.[17]

A small number of Nez Perce fighters, probably fewer than 200,[19] defeated or held off larger forces of the U.S. Army in several battles. The most notable was the two-day Battle of the Big Hole in southwestern Montana territory, a battle with heavy casualties on both sides, including many women and children on the Nez Perce side. Until the Big Hole the Nez Perce had the naive view that they could end the war with the U.S. on terms favorable, or at least acceptable, to themselves.[24] Afterwards, the war "increased in ferocity and tempo. From then on all white men were bound to be their enemies and yet their own fighting power had been severely reduced."[25]

The war came to an end when the Nez Perce stopped to make camp and rest on the prairie adjacent to Snake Creek in the foothills of the north slope of the Bear's Paw Mountains in Montana Territory, only 40 miles (64 km) from the Canada–United States border.

They believed that they had shaken off Howard and their pursuers, but they were unaware that the recently promoted Brigadier General Nelson A. Miles in command of the newly created District of the Yellowstone had been dispatched from the Tongue River Cantonment to find and intercept them. Miles led a combined force made up of units of the Fifth Infantry, and Second Cavalry and the Seventh Cavalry. Accompanying the troops were Lakota and Cheyenne Indian Scouts, many of whom had fought against the Army only a year prior during the Sioux War.

They made a surprise attack upon the Nez Perce camp on the morning of September 30. After a three-day standoff, Howard arrived with his command, on October 3 and the stalemate was broken. Chief Joseph surrendered on October 5, 1877,[26] and declared in his famous surrender speech that he would "fight no more forever."[26]

In total, the Nez Perce engaged 2,000 American soldiers of different military units, as well as their Indian auxiliaries. They fought "eighteen engagements, including four major battles and at least four fiercely contested skirmishes."[27] Many people praised the Nez Perce for their exemplary conduct and skilled fighting ability. The Montana newspaper New North-West stated: "Their warfare since they entered Montana has been almost universally marked so far by the highest characteristics recognized by civilized nations. "[28]

Surrender

By the time Chief Joseph formally surrendered on October 5, 1877, 2:20 pm,[29] European Americans described him as the principal chief of the Nez Perce and the strategist behind the Nez Perce's skilled fighting retreat. The American press referred to him as "the Red Napoleon" for the military prowess attributed to him, but the Nez Perce bands involved in the war did not consider him a war chief. Joseph's younger brother, Ollokot; Poker Joe, and Looking Glass of the Alpowai band were among those who formulated the fighting strategy and tactics and led the warriors in battle, while Joseph was responsible for guarding the camp.

Chief Joseph became immortalized by his famous speech:

I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohoolhoolzoote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say, "Yes" or "No." He who led the young men [Ollokot] is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are -- perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.

Joseph's speech was translated by the interpreter Arthur Chapman and was transcribed by Howard's aide-de-camp Lieutenant C. E. S. Wood. Among other vocations, Wood was a writer and a poet. His poem, "The Poet in the Desert" (1915), was a literary success, and some critics have suggested that he may have taken poetic license and embellished Joseph's speech.[30]

Aftermath

During the surrender negotiations, Howard and Miles had promised Joseph that the Nez Perce would be allowed to return to their reservation in Idaho. But, the commanding general of the Army, William Tecumseh Sherman, overruled them and directed that the Nez Perce were sent to Kansas. "I believed General Miles, or I never would have surrendered," Chief Joseph said afterward.

Miles marched his captives 265 miles (426 km) to the Tongue River Cantonment in southeast Montana Territory, where they arrived on October 23, 1877, and were held until Oct. 31. The able-bodied warriors were marched out to Fort Buford, at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers. On November 1, women, children, the ill and the wounded set out for Fort Buford in fourteen Mackinaw boats.

Between November 8 and 10, the Nez Perce left Fort Buford for Custer's post command at the time of his death; Fort Abraham Lincoln across the Missouri River from Bismarck in the Dakota Territory. About two hundred left in the mackinaws on November 9 guarded by two companies of the First Infantry; the rest traveled on horseback escorted by troops of the Seventh Cavalry en route to their winter quarters.

A majority of Bismarck's citizens turned out to welcome the Nez Perce prisoners, providing a lavish buffet for them and their troop escort. On November 23, the Nez Perce prisoners had their lodges and equipment loaded into freight cars and themselves into eleven rail coaches for the trip via train to Fort Leavenworth in Kansas.

One of the most extraordinary Indian Wars of which there is any record. the Indians displayed a courage and skill that elicited universal praise. They abstained from scalping: let captive women go free; did not commit indiscriminate murder of peaceful families, which as usual, and fought with almost scientific skill, using advance and rear guards, skirmish lines and field fortifications.

Over the protests to Sherman by the commander of the Fort, the Nez Perce were forced to live in a swampy bottomland. One author described the effects on the Nez Perce refugees: "the 400 miserable, helpless, emaciated specimens of humanity, subjected for months to the malarial atmosphere of the river bottom."[32]

Chief Joseph went to Washington in January 1879 to plead that his people be allowed to return to Idaho or, at least, be given land in Indian Territory, what would become Oklahoma. He met with the President and Congress, and his account was published in the North American Review.[33] While he was greeted with acclaim, the U.S. government did not grant his petition due to fierce opposition in Idaho. Instead, Joseph and the Nez Perce were sent to Oklahoma and eventually located on a small reservation near Tonkawa, Oklahoma. Conditions in "the hot country" were hardly better than they had been at Leavenworth.

In 1885, Joseph and 268 surviving Nez Perce were finally allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest. Joseph, however, was not permitted to return to the Nez Perce reservation but instead settled at the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington. He died there in 1904.

Depictions in media

Books

%252C_a_warrior_of_the_Nez_Perce_(1877).jpg.webp)

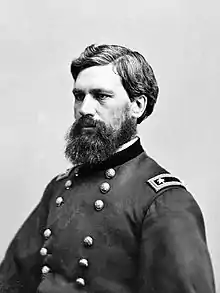

General Oliver Otis Howard was the commanding officer of U.S. troops pursuing the Nez Perce during the Nez Perce War of 1877. In 1881, he published an account of Joseph and the war, Nez Perce Joseph: An Account of His Ancestors, His Lands, His Confederates, His Enemies, His Murders, His War, His Pursuit and Capture, depicting the Nez Perce campaign.[34]

The Nez Perce perspective was represented by Yellow Wolf: His Own Story, published in 1944 by Lucullus Virgil McWhorter, who had interviewed Yellow Wolf, a Nez Perce warrior. This book is very critical of the U.S. military's role in the war, and especially of General Howard. McWhorter also wrote Hear Me, My Chiefs!, published after his death. It was based on documentary sources and had material supporting the historical claims of each side.

The fifth volume of William T. Vollmann's Seven Dreams cycle, The Dying Grass, offers a detailed account of the conflict.

Television

The 1975 David Wolper historical teledrama I Will Fight No More Forever, starring Ned Romero as Joseph and James Whitmore as General Howard, was well received at a time when Native American issues were receiving wider exposure in the culture. The drama was notable for attempting to present a balanced view of the events: the leadership pressures on Joseph were juxtaposed with the Army's having to carry out an unpopular task while an action-hungry press establishment looked on.

Song

Folk singer Fred Small's 1983 song "The Heart of the Appaloosa" describes the events of the Nez Perce War, highlighting the Nez Perce's skillful use of the Appaloosa in battle and in flight. The lyrics identify Chief Joseph's Nez Perce name, which translates as "Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain," and quotes extensively from his "I will fight no more forever" speech.

Texas country band Micky & the Motorcars released the song "From Where the Sun Now Stands" on their 2014 album Hearts from Above. The song chronicles the flight of the Nez Perce through Idaho and Montana.

See also

References

- 1 2 Nez Perce, Summer 1877: The US Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis, Jerome A. Greene, Appendix A: "US Army Casualties, Nez Perce War 1877"

- ↑ Josephy, Alvin M., Jr. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven: Yale U Press, 1965, p. 632

- ↑ Forest Service: Nez Perce Historic National Trail

- ↑ Robert G. Hays: A race at bay: New York Times editorials on "the Indian problem," 1860–1900; p. 243: Southern Illinois University Press (1997) ISBN 0-8093-2067-3

- ↑ "A LESSON FROM THE NEZ PERCES". The New York Times. 1877-10-15. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ↑ Trafzer, Clifford E. (Fall 2005). "Legacy of the Walla Walla Council, 1955". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 106 (3): 398–411. doi:10.1353/ohq.2005.0006. ISSN 0030-4727. S2CID 166019157. Archived from the original on 2007-01-05.

- ↑ Center for Columbia River History: Nez Perce Treaty, 1855 Archived 2007-01-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Hampton, Bruce. Children of Grace: The Nez Perce War of 1877. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1994, pp 28–29

- ↑ Clute, Willard Nelson (1907). The American botanist, devoted to economic and ecological botany, Volumes 11–15. W.N. Clute & co. p. 98.

- ↑ Mathews, Daniel (1999). Cascade-Olympic Natural History: a trailside reference. Raven Editions. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-9620782-1-7.

- ↑ Greene, Jerome A. (2000). Nez Perce Sumer 1877: The U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis. Helena, Montana: Montana Historical Society Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-917298-82-9.

- ↑ Hoggatt, Stan (1997). "Political Elements of Nez Perce history during mid-1800s & War of 1877". Western Treasures. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Charles F. (2005). Blood struggle: the rise of modern Indian nations. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 40–41. ISBN 0-393-05149-8.

- ↑ Josephy, Alvin M., Jr. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. Boston: Mariner, 1997, pp 428–29.

- ↑ Hampton, pp. 32–36, 43

- ↑ West, Elliott, pp. 14–15

- 1 2 3 Malone, p. 135

- ↑ Josephy, Jr., Alvin M. The Nez Perce Indians the Opening of the Northwest, New Haven: Yale U Press, 1965, p. 504. Toohoolhoolzote shared a jail cell with an amiable but drunken soldier, Trumpeter John Jones. They two got along famously, but Jones, a few weeks later, became the first soldier killed in the Nez Perce War. McDermott, p. 60

- 1 2 3 "Chief Joseph". New Perspectives on the West. The West Film Project/WETA/PBS/. 2001. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

- 1 2 West, Elliott, pp. 5–6

- ↑ Greene, Jerome A. "online ebook title_ "Nez Perce, Summer 1877; US Army and the Nimiipoo Crisis"". US Government National Parks and Historic Sites. Montana Historical Press. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ McDermott, John D. Forlorn Hope. Boise: Idaho State Historical Society, 1978, pp. 12, 54

- ↑ West, p. 4

- ↑ Josephy, pp. 587–88

- ↑ Beal, Merrill D. I Will Fight No More Forever: Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce War. Seattle: U of WA Press, 1963, p. 130

- 1 2 Malone, et al. Montana, p. 138

- ↑ Josephy, pp. 632–33

- ↑ Jerome A. Greene, Alvin M. Josephy: Nez Perce Summer, 1877: The US Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis; ISBN 978-0-917298-82-0

- ↑ Anderson, Frank W (1999). Chief Joseph and the Cypress Hills. Humboldt, Saskatchewan: Gopher Books. p. 95. ISBN 0-921969-24-4. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- ↑ Sherry L. Smith: The View from Officers' Row: Army Perceptions of Western Indians. p. 136; University of Arizona Press (1991) ISBN 0-8165-1245-0

- ↑ Josephy, p. 635

- ↑ Josephy, p. 637

- ↑ Joseph, Young, and William H. Hare. “An Indian's Views of Indian Affairs.” The North American Review, vol. 128, no. 269, 1879, pp. 412–433. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25100745. Accessed 19 Aug. 2020.

- ↑ Oliver Otis Howard, Nez Perce Joseph: An Account of His Ancestors, His Lands, His Confederates, His Enemies, His Murders, His War, His Pursuit and Capture. Boston, MA: Lee and Shepard, 1881.

Further reading

- Hampton, Bruce (1994). Children of Grace-The Nez Perce War of 1877. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-1991-X.

- Greene, Jerome A. (2000). Nez Perce Summer-The U.S. Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis. Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-917298-68-3.

- Janetski, Joel C. (1987). Indians in Yellowstone National Park. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-724-7.

- Malone, Michael P., Richard B. Roeder and William L. Lang (1991). Montana: A History of Two Centuries. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97129-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Nichols, Roger L. (2013). Warrior Nations: The United States and Indian Peoples. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- West, Elliott (2009). The Last Indian War: The Nez Perce Story. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513675-3.

- West, Elliott (Autumn 2010). "The Nez Perce and Their Trials: Rethinking America's Indian Wars". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. Helena, Montana: Montana Historical Society: 3–18.

- Josephy, Alvin (2007). Nez Perce Country. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7623-9.

External links

- Online copy of Nez Perce Joseph: an account of his ancestors, his lands, his confederates, his enemies, his murders, his war, his pursuit and capture (1881)

- Online copy of Yellow Wolf: His Own Story (1944)

- Burial ground for Nez Perce in Oklahoma

- Timeline for the flight of the Nez Perce

- 1877 accounts of US Casualties

- Listing of US Casualties

- Sacred Journey of the Nez Perce Documentary produced by Montana PBS

- Lewiston Morning Tribune - July 24, 1977 - special 18-page section on the centennial of Nez Perce War