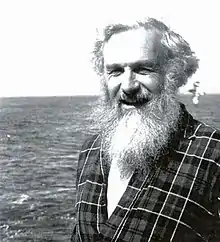

Nigel Bonner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | William Nigel Bonner 15 February 1928 London, England |

| Died | 27 August 1994 (aged 66) |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University College London |

| Known for | Study of Antarctic fur seals - marine mammals - introduced reindeer - marine ecology |

| Spouse | Jennifer |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Polar Medal |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Zoology, Antarctic marine mammals, Antarctic ecology |

| Institutions | British Antarctic Survey - Natural Environment Research Council - Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research |

| Academic advisors | J.B.S. Haldane, Richard John Harrison |

William Nigel Bonner (15 February 1928 – 27 August 1994) was a British zoologist, Antarctic marine mammal specialist, author and ecologist. The topics of his books and scientific publications included marine animals, reindeer and the ecology of the Antarctic. He headed the Life Sciences Division of the British Antarctic Survey from 1974 to 1986, and served as deputy director from 1986 to 1988. Bonner received the Polar Medal in 1987, in recognition of his work in Antarctica.[1]

Bonner was recognized for his research on the Antarctic fur seal of South Georgia, publishing in 1968 a highly respected monograph, which was the "first modern study of the species". At the time of his death in 1994, it was still referred to and quoted. He also conducted the first research on the introduced reindeer that lived on South Georgia. His 1958 monograph on the reindeer remained the sole source of information for many years.

After retirement, Bonner was a leader in the environmental reclamation of South Georgia, and worked to establish the South Georgia Museum, where the Bonner Room is dedicated in his honour. The Bonner Lab at Rothera Research Station on the Antarctic Peninsula is named in his honour, as is Bonner Beach in Larsen Harbour, where Weddell seals breed.

Early life and education

William Nigel Bonner, known as Nigel, was born in London in 1928. He was the child of Frederick John Bonner and Constance Emily (née Hatch) Bonner.[2] His father, an Indian Army veteran, died in 1931. Constance was left to raise three-year-old Nigel and his older brother, five-year-old Gerald, on a schoolteacher's salary.[3]

Later in their lives, Nigel became a respected zoologist,[2] and Gerald Bonner became a noted Early Church historian and scholar.[4]

Following in his elder brother's footsteps, he also received a County Scholarship to the Stationers' Company's School in Hornsey, where he was educated. In 1939, the school was evacuated to Wisbech for several years, due to World War II. During this time, he was lodged with a slaughterman, which may have contributed to his later "matter of fact" approach to collecting large animals for scientific research. While in Wisbech he showed an early interest in natural history, by collecting beetles. This interest was supported by one of his schoolmasters,[5] Ronald Englefield. The school returned to London in 1942.[5]

By the time he joined the Army for National Service, in 1946, World War II was over. In 1947, he was commissioned into the Royal Artillery, and stationed on the Isle of Wight. There, he continued to pursue his budding zoological interests, by studying beetles, dragonflies and adders. He was demobilized in 1948.[5]

After leaving the Army, he worked as a lab technician, and then studied biology at the Polytechnic of North London, as preparation for further education. In 1950, he entered University College London to study special zoology. Here, Bonner met J.B.S. Haldane, who was one of his instructors. In 1955, he worked with Richard John Harrison, a noted anatomist, who assisted Bonner in processing his Antarctic fieldwork.[5]

Initial work in Antarctic

Due to his early interest in beetles, Bonner had planned to pursue entomological studies in East Africa. Instead, he travelled to Antarctica in 1953, with a friend from college Bernard Stonehouse, on a research expedition to South Georgia, where Stonehouse intended to study king penguins.[2]

Setting forth on a whaling transport, Polar Maid, they landed at Leith Harbour, at which point Bonner developed appendicitis, and was whisked off to hospital for surgery. Once recovered, Bonner joined his friend on Paul Beach[6] in the Bay of Isles, where they set up their base in a garden shed. For the following fifteen months, between 1953-1955, Bonner (and Stonehouse) worked for the Falkland Islands' Dependencies Survey, later known as the British Antarctic Survey. Bonner collected specimens from the southern elephant seal, Mirounga leonina.[7][2][5] Returning to England in 1955, he spent a year at London Hospital Medical School, working with Richard John Harrison, to process and publish the results of his research. The publication provided reproductive biologists with new information regarding elephant seals,[7] and was accompanied by photographs that he made, despite the primitive and difficult field conditions.[2][5]

Career

.jpg.webp)

After processing his elephant seal research materials in England, Bonner returned to South Georgia in 1956, where he was employed as a biologist and sealing inspector by the Government of the Falkland Islands, who held administrative jurisdiction over the territory at the time. Bonner was charged with implementing a wildlife management plan, which was intended to rescue the elephant seals. Their population had suffered from years of over-hunting.[2] By working closely with the Norwegian sealers, and travelling from beach to beach, he became very familiar with South Georgia. During this time, he tagged elephant seals, and organized collections of their teeth, to track the ages of the seals. Through his work with the sealers, the industry was transformed into a "rational sustained-yield management of a natural resource."[5]

Beginning in early 1957, Bonner spent several years in the Antarctic. His initial one-year contract became a six-year contract. His wife and son joined him and lived on South Georgia for two and half years, between 1958 and 1961. In addition to his initial research on elephant seals, he had begun to study the Antarctic fur seal on visits to Bird Island, off the western tip of South Georgia, and continued this research for several years. Bonner had visited Bird Island in 1956, and was possibly the first biologist to do so since 1936. There, he documented evidence of the recovery of the population of fur seals, due to protective legislation. Bonner's wife, Jennifer and their young son joined him, at one point, for a 12 day stay. He continued to visit the island, through 1962. As a culmination of his work, in 1968 he published a highly respected monograph, which was the "first modern scientific study of the species"; at the time of his death in 1994, it was still referred to and quoted.[5] While living on South Georgia, Bonner and his family were befriended by whalers, and learned to speak Norwegian. Bonner gained "a deep knowledge of South Georgia and its whaling industry."[2]

Bonner also conducted research on the introduced reindeer in South Georgia, on the Barff Peninsula of South Georgia island.[2] Beginning in the early 20th century, as South Georgia was growing into the world's largest whaling centre, reindeer from Norway were released on the island. They were intended to provide fresh meat to whalers and for recreational hunting.[8] By following the deer, and collecting seven stags, Bonner established their food source as tussock grass, not lichens, as had been previously thought. His 1958 monograph on the reindeer remained the sole source of information for many years.[5]

Bonner was employed at Sir John Cass College as a zoology lecturer, from 1962 through 1967, and then became the director of the Natural Environment Research Council's Seals Research Unit. At NERC, Bonner's team researched Grey seals and Harbor seals, who were being hunted, both to protect fisheries and to harvest their skins.[2] He assisted with drafting the Conservation of Seals Act 1970, continued in an advisory capacity, under the aegis of NERC.[1][5]

In 1974, he was appointed as head of the Life Sciences Division of the British Antarctic Survey. He was appointed as deputy director in 1986, and served in this position until his retirement in 1988. During his time at BAS, he was invited to lecture at the College of Fisheries in Seattle, Washington. The series of lectures he presented led to his book, Seals and Man: a study of interactions.[5]

Bonner chaired the Conservation Subcommittee of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) from 1974 to 1992, which addressed conservation issues within the Antarctic environment.[2] Bonner was chosen as convenor of the newly-formed Group of Specialists on Environmental Affairs and Conservation (GOSEAC) in 1989 and continued to serve in this capacity through 1992.[9]: 5–7, 11

Post-retirement

Environmental clean-up

After his retirement from the British Antarctic Survey, he periodically returned to South Georgia, beginning in 1989, and worked to clear environmental hazards associated with the now-deserted, and frequently vandalized whaling stations.[10]

Bonner was appointed by the Commissioner for South Georgia, William Fullerton to supervise a team of marine engineers, who were charged with evaluating and reporting on the environmental hazards. After the whaling industry ended on the island in 1965, the station buildings, with their large stores of diesel fuel were often scavenged by boat crews. Leaking tanks were contaminating the soil with heavy fuel oil and attracting elephant seals, who rolled in these sun-warmed areas and became coated in oil. Funds were provided, and in 1991, Bonner organized a clean-up team, who removed 3000 tonnes of heavy fuel oil, in addition to asbestos and fibreglass insulation, lead-acid batteries and 75 tonnes of concentrated sulphuric acid.[11]

South Georgia Museum

Also in 1991, with financial support from the South Georgia government, Bonner and his team renovated and restored the manager's house (Villa) at Grytviken.[10] Through his efforts, the building was repurposed to serve as the South Georgia Whaling Museum, which later widened its scope and became the South Georgia Museum, in 1992.[12] As a result of his many years in the field, he served as a repository of knowledge regarding the "now extinct way of life of the whalers and sealers".[2]

.jpg.webp)

In October 1993, Bonner presented a lecture at the Kendall Whaling Museum in Sharon, Massachusetts, about the founding of the South Georgia Museum. During the first six weeks after the museum opened, and despite its remote location, 480 people had viewed the various exhibits. Noting that the visitors had been impressed, he said:[11][5]

If this causes them to think a little more deeply about the whaling industry, the management of natural resources, and the society of whalers, I think we shall have achieved our objective.

— Nigel Bonner, lecture to the Kendall Whaling Museum, 1993

Personal life

Bonner met Jennifer Sachs during his studies at University College London. In August 1955 they married at Hampstead Registry Office. Between 1958 and 1961, Jennifer and their infant son lived with Bonner on South Georgia Island.[1] The couple learned to speak Norwegian from their friends amongst the whalers.[5] The local Norwegian blacksmith became an unofficial bestefar, or grandfather, to the little boy.[2]

Nigel Bonner suffered a heart attack on 27 August 1994 and died at his home in Godmanchester, England. According to his wishes, his ashes were strewn at Bird Island, South Georgia.[2] On 22 October 1994, a memorial gathering was hosted at BAS, attended by some 200 people.[5]

Professional affiliations and awards

In 1987, he received the Polar Medal, in recognition of his achievements in the Antarctic.[5] It is awarded to those who have "personally made conspicuous contributions to the knowledge of Polar regions" and for having "undergone the hazards and rigours imposed by the Polar environment."[13]

Bonner was president of the Mammal Society for two terms. The first was from 1985 to 1991. His second term began in 1993 and ended with his death in 1994. Bonner was the recipient of the Society's Silver Medal.[5]

He was a Fellow of the Zoological Society of London, and was named to their publications committee in 1968, and continued to serve until his death in 1994. He served as editorial board member for Polar Record, Polar Biology, and Marine Mammal Science.[1] He was also a Fellow of the Linnean Society of London as well as the Institute of Biology.[5] Bonner was a Charter Member of The Society for Marine Mammalogy, when it was established in 1981.[14]

Legacy and recognition

Bonner Beach,[15] at Larsen Harbour, South Georgia, where the Weddell seals gather to breed, is named in his honour.[2]

The Bonner laboratory at the Rothera Research Station in the British Antarctic Territory.[2] created in 1996–1997, was named in his honour.[16]

The South Georgia Museum,[17] has dedicated the Bonner Room as a tribute to his pioneering work in establishing the Museum.[12][18]

Works

Publications

- Bonner, W. Nigel. Reproductive Organs of Fœtal and Juvenile Elephant Seals. Nature176, 982–983 (1955)

- Bonner, W. Nigel. The Introduced Reindeer of South Georgia 1958. Cambridge: British Antarctic Survey (BAS Scientific Report 22)

- Bonner, W. Nigel. The Fur Seal of South Georgia 1958. Cambridge: British Antarctic Survey (BAS Scientific Report 56)

- Bonner, W. Nigel. (1958) Exploitation and Conservation of Seals in South Georgia Oryx. 4 (6): 373–380. via Cambridge University Press.

- Bonner, W. Nigel. Seals of the Galapagos Islands Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, Volume 21, Issue 1-2, January 1984, Pages 177–184,

- Bonner, W. Nigel. (January 1987) "Antarctic science and conservation — The historical background" Environment International / 13 pp 19–25

- Bonner, W. Nigel. "Environmental Assessment in the Antarctic." Ambio 18, no. 1 (1989): 83-89.

Books

- Ecology of the Antarctic. 1980. London: Academic Press. (with R.J. Berry)

- Key environments–Antarctica. 1985. Oxford: Pergamon Press, (with D.W.H. Walton)

- Conservation areas in the Antarctic. 1985. Cambridge: Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, (with R.I. Lewis Smith)

- Whales. 1980. Poole: Blandford Press.

- Whales of the World. 1989. London: Blandford Press

- Seals and Man: a study of interactions. 1982. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- The Natural History of Seals. 1989. London: Christopher Helm.

- Seals and Sea Lions of the World. 1994. London: Blandford Press

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Laws, Richard (October 1995). "WILLIAM NIGEL BONNER 1928–1994". Marine Mammal Science. 11 (4): 596. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1995.tb00686.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "BONNER, (WILLIAM) NIGEL 1928 – 1994". www.falklandsbiographies.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ↑ Hardy, Daniel W (2000). "Gerald Bonner: an appreciation". In Dodaro, Robert; Lawless, George (eds.). Augustine and His Critics: Essays in Honour of Gerald Bonner. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-20062-8.

- ↑ "Passing of Prof. Gerald Bonner – Durham University". www.dur.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Laws, Richard M. (3 January 1995). "William Nigel Bonner". Polar Record. 31 (176): 67–70. doi:10.1017/S0032247400024888. S2CID 128891684. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2020 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ "Antarctica Detail". geonames.usgs.gov.

- 1 2 "Reproductive Organs of Fortaleza and Juvenile Elephant Seals". www.bas.ac.uk.

- ↑ Bell, Cameron M. & Dieterich, Robert A. (2010). "Translocation of reindeer from South Georgia to the Falkland Islands". Rangifer. 30 (1): 1–9. doi:10.7557/2.30.1.247. hdl:10535/6453.

- ↑ "The Environmental Years (1988–97)". Science in the Snow. Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - 1 2 "History". sgmuseum.gs. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- 1 2 "Lecture to the Kendall Whaling Museum on the beginnings of South Georgia Museum by Nigel Bonner, 16th October 1993". sgmuseum.gs.

- 1 2 "Bonner Room". sgmuseum.gs. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2020.

- ↑ copied from Polar Medal, see attribution there, etc.

- ↑ "Society for Marine Mammalogy". Society for Marine Mammalogy.

- ↑ "Bonner Beach". geonames.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ↑ "Bonner Laboratory and dive facility". bas.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ "South Georgia Museum History". sgmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ↑ "South Georgia Museum – Government of South Georgia & the South Sandwich Islands".