| Night of the Lepus | |

|---|---|

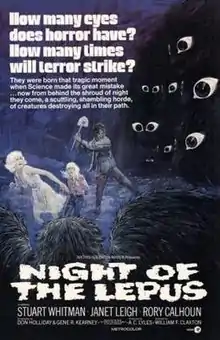

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | William F. Claxton |

| Screenplay by | Don Holliday Gene R. Kearney |

| Based on | The Year of the Angry Rabbit by Russell Braddon |

| Produced by | A. C. Lyles |

| Starring | Stuart Whitman Janet Leigh Rory Calhoun |

| Cinematography | Ted Voigtlander |

| Edited by | John McSweeney Jr. |

| Music by | Jimmie Haskell |

Production company | A.C. Lyles Productions |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Night of the Lepus (also known as Rabbits) is a 1972 American science fiction horror film directed by William F. Claxton and produced by A. C. Lyles. Based upon Russell Braddon's 1964 science fiction novel The Year of the Angry Rabbit, the plot concerns an infestation of mutated rabbits.[1][2][3]

The film was the first science fiction work for producer Lyles and for director Claxton, both of whom came from Western film backgrounds. Character actors from Westerns the pair had worked on were brought in to star, including Stuart Whitman, Janet Leigh, Rory Calhoun and DeForest Kelley. Shot in Arizona, including scenes filmed underground within Collosal Cave Mountain Park, Night used domestic rabbits filmed against miniature models and actors dressed in rabbit costumes for the attack scenes.

Widely panned by critics for its silly premise, poor direction, stilted acting and bad special effects, the film's biggest failure is considered to be the inability to make the rabbits seem scary. Night of the Lepus has since gained cult status for its laughably poor quality.

Plot

Rancher Cole Hillman seeks the help of college president Elgin Clark to combat thousands of rabbits that have invaded the area after their natural predators, coyotes, were killed off. Elgin asks for the assistance of researchers Roy and Gerry Bennett because they respect Cole's wish to avoid using cyanide to poison the rabbits. Roy proposes using hormones to disrupt the rabbits' breeding cycle and takes some rabbits for experimentation. One is injected with a new serum believed to cause birth defects. However, the Bennetts' daughter Amanda loves the injected rabbit, so she switches it with one from the control group. Amanda is then given the injected rabbit as a pet, but it soon escapes.

While inspecting the rabbits' old burrowing areas, Cole and the Bennetts find a large, unusual animal track. Meanwhile, Cole's son Jackie and Amanda go to a gold mine to visit Jackie's friend Billy, but find him missing. Jackie finds more of the animal tracks in Billy's shed, while Amanda goes into the mine and runs into an enormous rabbit with blood on its face. Screaming in terror, she runs from the mine.

Mutilated bodies begin to crop up around town, including those of Billy, a truck driver, and a family of four. Elgin, the Bennetts, Cole, and Cole's two ranch hands Frank and Jud go to the mine to try to kill the rabbits with explosives. As Elgin and Frank set charges on top of the mine, Roy and Cole enter the shaft to get pictorial evidence. Outside, a rabbit surfaces and attacks Jud before Gerry can shoot it. Roy and Cole escape the rabbits in the mine and run outside as the explosives are detonated.

The explosives fail to kill the rabbits, and that night they attack Cole's ranch, killing Jud while Cole, Frank, Jackie, and Cole's housekeeper Dorothy escape into the storm shelter. The rabbits make their way to the general store, killing shopkeeper Mildred and eating and killing everyone else they find in the small town of Galanos before taking refuge in the buildings for the day. In the morning, Gerry and Amanda leave to avoid the coming press, but get stuck along a sandy stretch of road. Roy and Elgin update Sheriff Cody on the situation and, after realizing the rabbits have escaped the mine, call in the National Guard. As night falls, the rabbits leave Galanos to continue their rampage, making their way to the main town of Ajo and eating and killing everyone in their path. Cole proposes using a half-mile wide stretch of electrified railroad track as a fence to contain and kill the rabbits. They recruit a large group of people at a drive-in theater to help herd the rabbits with their car lights, with assistance from the machine gun fire of the National Guard.

Thousands of rabbits make their way into the trap, where they are shot and electrocuted. At the film's ending, Cole tells Roy that normal rabbits, as well as coyotes, have returned to the ranch.

Cast

- Stuart Whitman as Roy Bennett

- Janet Leigh as Gerry Bennett

- Rory Calhoun as Cole Hillman

- DeForest Kelley as Elgin Clark

- Paul Fix as Sheriff Cody

- Melanie Fullerton as Amanda Bennett

- Chris Morrell as Jackie Hillman

- Chuck Hayward as Jud

- Henry Wills as Frank

- Francesca Jarvis as Mildred

- William Elliott as Dr. Leopold

- Robert Hardy as Professor Dirkson

- Richard Jacome as Deputy Jason

- Evans Thornton as Major White

- Robert Gooden as Leslie

- Don Starr as Cutler

- David McCallum as Police Officer

Isaac Stanford Jolley makes an appearance as a dispatcher, while Jerry Dunphy has a cameo as a television newscaster. DeForest Kelley and Paul Fix had both played the same role of Chief Medical Officer (although different characters) of the USS Enterprise on Star Trek.

Production

Development

The script for Night of the Lepus was based upon Australian author Russell Braddon's science fiction novel The Year of the Angry Rabbit (1964).[4]

A. C. Lyles, known primarily for producing western films, would make Night of the Lepus his first and only science fiction production. To craft the film, he pulled together people he had worked with on other Westerns. Gene R. Kearney and Don Holliday were tasked with converting the novel to a screenplay. In doing so, they removed nearly all aspects of the novel (a black comedy, the plot of which focused on Australia dominating the world with a superweapon inadvertently created through the rabbits), and moved its setting from Australia to Arizona.

Filming

Principal photography took place at the Old Tucson Studios in Tucson, Arizona, a site well known for its use in Western pictures.[5] Filming commenced at the end of January 1972 and concluded in early March.[6]

According to Turner Classic Movies' David Kalat, director Claxton also came from a Western film background. In directing Night of the Lepus, he applied the same techniques used in his other films and declined the use of "standard" horror effects that would have enhanced the atmosphere, such as "canted camera angles, dark shadows, [and] eerie music."

Rory Calhoun was cast as rancher Cole Hilman, whose ranch would be the start of the rabbit explosion. Well known for his Western work, Lepus put him in unfamiliar territory as it was his first science fiction role; however, he found familiarity in the Western film trappings and his role as a rancher.[5]

Janet Leigh, who played Gerry Bennett, accepted the role because filming was close to home, allowing her to travel on weekends and allowing her family to visit her on set. Though she felt the script "read well", she declined to allow her two children to play minor roles as she did not want them to see or be part of any type of horror film.[7] She later said the film lacked an "ideal director" to bring the script to life, and the film failed, in part, because it was impossible to make a "bunny rabbit menacing".[5]

She later reflected "No one put a gun to my head and said I had to do it. What no one realized was that, no matter what you do, a bunny rabbit is a bunny rabbit [laughs]. A rat, that can be menacing—so can a frog. Spiders or scorpions or alligators, they could all work in that situation, and they have. But a bunny rabbit?! How can you make a bunny rabbit menacing?"[8]

Fellow The Rifleman actor Paul Fix was given the role of the sheriff of the town under siege, while DeForest Kelley, who frequently guest-starred in Westerns, was cast as Elgin Clark, the college president who asked researchers to try to stop the rabbits.

The domesticated rabbits used differed greatly in appearance from the wild rabbits that were plaguing the southwest at the time. In Night, this was explained by stating that they were descended from recent rabbit farm escapees.[5] To depict the rabbit attacks, a combination of techniques were used. For some scenes, the rabbits were filmed in close-up stomping on miniature structures in slow motion.[9] For attack scenes, they had ketchup smeared on their faces.[4] For others, human actors were shown wearing rabbit costumes.[4][5][9]

Release and reception

Night of the Lepus was theatrically released on July 26, 1972.[6]

Originally titled Rabbits, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer changed the title and avoided including any rabbits in most promotional materials to try to keep the featured mutant creatures a secret. However, the studio itself broke the secret by issuing rabbit's foot-themed promotional materials prior to release.[10]

Contemporary

In a July 1972 issue of The New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote it was not an "especially memorable movie", that it was typical for the genre of science fiction horror, and that it failed because the rabbits, despite attempts to make them "appear huge and scary, still look like Easter bunnies".[11] In an October 1972 issue, fellow critic Roger Greenspun panned it for not "even reasonably try[ing]" to make the rabbits scary, its reliance on "tired clichés of monsterdom", "technical laziness" in its special effects, "stupid story", and "dumb direction that leaves the film in limbo" between a horror film and a fairy tale.[12] In the Monthly Film Bulletin, Tom Milne felt Night of the Lepus had a promising beginning before moving into a "well-worn horror groove", such as the effort to trap Gerry and Amanda alone in a deserted area for a last-minute rescue. Noting that the film had "a certain overall charm and several striking sequences", he felt the film would have been more successful if it "had the courage of its convictions – and its realism". As an example, he points to the scene following the attack on the Calhoun ranch, in which Cole is walking into town, and tourists refuse to stop and pick him up because he has a gun. The tourists then go to the small town where the rabbits have killed Mildred and are hiding in the general store building. Rather than becoming the next victims, the family call it a ghost town and leave.[13] In the 1977 piece Dark Dreams 2.0: A Psychological History of the Modern Horror Film, Charles Derry compared it to the earlier successful works The Birds and Willard, particularly the former, noting that both featured a "loveable creature". Though he felt the special effects were poor, he felt Night of the Lepus successfully tied into ongoing fears of throwing ecology out of balance, with the rabbits serving as an appropriate metaphor for human fears about overpopulation.[14]

Retrospective

AllMovie's Jeremy Wheeler felt the film was "all good, unintentionally campy fun" and "silly to its core". Noting that the special effects were "obvious", he criticized the "truly heinous dialogue" and remarked that Leigh "slums it" by appearing in the film.[9] In Stories Rabbits Tell: A Natural and Cultural History of a Misunderstood Creature, Susan E. Davis and Margo DeMello considered the film an "entertaining romp", praising the "alarmingly realistic" circumstances behind the rabbit mutations, while criticizing the "notoriously badly done" special effects and the rabbits being made to "roar" during their attacks. Calling it "one of [the] worse career moves" for Kelley and Leigh, they criticized the ending in which all the rabbits were killed, calling them "unwitting victims...of human attempts to control nature".[4] In his book Videohound's Horror Show: 999 Hair-Raising, Hellish, and Humorous Movies, critic Mike Mayo panned the film, calling the script "lame", the scenes of the rabbits "hopping around H0 scale sets in slow motion" humorous, and the rabbits just not scary. He also criticized the principal performers, stating that the film featured a "group of so-so character actors", except Leigh who he considered a "star", and that all gave "wooden performances".[15]

John J. Puccio of DVDTown.com felt Lepus would have been better had it been an intentionally humorous horror spoof, rather than a legitimate attempt at making a horror film with killer rabbits. Stating that it was in the "so-bad-it's-good" category for only two minutes, he found the actors to be "stiff and uninvolved" in delivering their lines, and that it seemed more like an "old television horse opera" than a horror film with more slow-paced filler than action sequences, and the few bits of action ruined by the "corniest possible 'action' music".[16] AMC Film Critic's Christopher Null states that it is famous as "one of the worst films ever made". He heavily criticizes Claxton, feeling that he "just seems wholly incapable of making the movie remotely frightening, or even of making much sense" and that the bad special effects "make the entire film a huge joke".[17] Reviewing the title for Classic-Horror.com, Julia Merriam gave Night of the Lepus credit for attempting to be a "socially-conscious eco-horror", but criticized the slow pacing, bad dialog, poor editing with a heavy reliance on stock footage that did not appear to be from the same film, and senseless character actions such as entering a rabbit-filled cave just to photograph them. She also criticized the film's obvious use of people in rabbit suits, but concluded its biggest flaw was that "fluffy bunnies just aren't scary".[18]

In Horror Films of the 1970s, John Kenneth Muir felt it one of the "most ridiculous horror film[s] ever conceived", with a poor blend of horror and environmentalism that resulted in it being more of a comedy. He criticized the "primitive special effects", badly done editing and laughable dialogue, and noted that while the rabbits and actors are rarely seen on screen together, the filmmakers used obviously fake rabbit paws and people in rabbit suits for the few scenes calling for human/rabbit interactions. Like most critics, he pointed out that the rabbits were "cute bunnies" rather than "fanged, disease-ridden mutated creatures", but he felt the actors did the best they could with the material, and praised them for "[keeping] straight faces as they heroically stand against the onslaught of the bunnies".[19]

Home media

The film did not receive a home video release until October 4, 2005 when Warner Home Video brought it out on DVD, with the only special features being the film's trailer and different language and subtitle options. After this went out of print, it was rereleased on DVD-R by the Warner Archive Collection on November 10, 2011.[20]

Scream Factory later released a Blu-ray on June 19, 2018.[21]

A VOD featuring comedic commentary by Michael J. Nelson, Bill Corbett and Kevin Murphy of RiffTrax (an offshoot of Mystery Science Theater 3000) was released on February 7, 2014.[22]

See also

References

- ↑ 'Night of the Lepus'|Top 10 Killer-Animal Movies|TIME.com

- ↑ In Praise of Night of the Lepus - ComingSoon.net

- ↑ Shock Cinema Magazine

- 1 2 3 4 Davis, Susan E.; DeMello, Margo (2003). "4. Trix Are for Kids!: The Rabbit as Contemporary Icon". Stories Rabbits Tell: A Natural and Cultural History of a Misunderstood Creature. New York, New York: Lantern Books. pp. 195–197. ISBN 1-59056-044-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kalat, David. "Night of the Lepus: TCM Underground - Insider Info". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- 1 2 "Night of the Lepus (1972)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ O'Brian, Jack (May 16, 1972). "Callas' New Beau Dean At Juilliard". Sarasota Journal. p. 6-B.

- ↑ Weaver, Tom (July 1988). "Janet Leigh Mistress of Menace". Starlog. No. 132. p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Wheeler, Jeremy. "Night of the Lepus Review". Allmovie. Retrieved January 3, 2010.

- ↑ BOTH ORIGINAL STAR TREK DOCTORS CAME TOGETHER TO FIGHT GIANT MAN-EATING BUNNIES IN 1972 - H&I|All Star Trek

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (July 16, 1972). "King Kong, Where Are You?". The New York Times. pp. D1, D5–D6.

- ↑ Greenspun, Peter (October 5, 1972). "Night of the Lepus Shoes Peter Rabbit's Other Side". The New York Times. p. 56.

- ↑ Milne, Tom (March 1973). "Monthly Film Bulletin". 40 (468/479): 55. ISSN 0027-0407.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Derry, Charles (2009). Dark Dreams 2.0: A Psychological History of the Modern Horror Film. McFarland. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7864-3397-1.

- ↑ Mayo, Mike (February 1, 1998). VideoHound's Horror Show: 999 Hair-Raising, Hellish and Humorous Movies. Detroit: Visible Ink Press. p. 257. ISBN 1-57859-047-7. OCLC 39052368.

- ↑ Puccio, John J. (October 9, 2005). "Night Of The Lepus - DVD review". DVDTown.com. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ Null, Christopher (2005). "Night of the Lepus". AMC's Filmcritic.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ Merriam, Julia (April 30, 2007). "Night of the Lepus (1972)". Classic-Horror.com. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ Muir, John Kenneth (August 20, 2002). "1972: Night of the Lepus". Horror Films of the 1970s. McFarland & Company. pp. 216–219. ISBN 0-7864-1249-6.

- ↑ Night of the Lepus WBShop.com

- ↑ Night Of The Lepus at Shout! Factory

- ↑ RiffTrax