Sado

佐渡市 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sado City | |||||

.jpg.webp)

| |||||

Flag  Seal | |||||

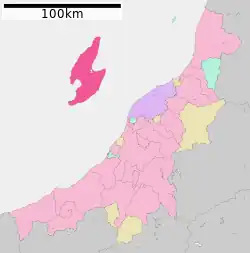

Location of Sado in Niigata Prefecture | |||||

Sado | |||||

| Coordinates: 38°01′06″N 138°22′06″E / 38.01833°N 138.36833°E | |||||

| Country | |||||

| Island | Honshu | ||||

| Region | Chūbu | ||||

| Prefecture | Niigata Prefecture | ||||

| First official recorded | 135 AD | ||||

| As city settled for Ryōtsu | November 3, 1954 | ||||

| As merger with neighbor town and current city's name date | March 1, 1954 | ||||

| Government | |||||

| • Mayor | Koichiro Takano | ||||

| Area | |||||

| • Total | 855.69 km2 (330.38 sq mi) | ||||

| Population (June 1, 2023) | |||||

| • Total | 48,195 | ||||

| • Density | 56/km2 (150/sq mi) | ||||

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Japan Standard Time) | ||||

| Address | 232 Chigusa, Sado-shi, Niigata-ken | ||||

| Climate | Cfa | ||||

| Website | www | ||||

| Symbols | |||||

| Flower | Daylily | ||||

| Tree | Thujopsis | ||||

Sado (佐渡市, Sado-shi) is a city located on Sado Island (佐渡島, Sado-shima/Sado-ga-shima) in Niigata Prefecture, Japan. Since 2004, the city has comprised the entire island, although not all of its total area is urbanized. Sado is the sixth largest island of Japan in area following the four main islands and Okinawa Island (excluding the Northern Territories). As of June 1, 2023, the city has an estimated population of 48,195 and a population density of 56.3 inhabitants per square kilometre (146/sq mi). The total area is 855.69 square kilometres (330.38 sq mi).

History

Political formation of the island

The large number of pottery artifacts found near Ogi in the South of the island demonstrate that Sado was populated as early as the Jōmon period.

The Nihon Shoki mentions that Mishihase people visited the island in 544 (although it is unknown whether Tungusic people effectively came).

The island formed a distinct province, the Sado Province, separate from the Echigo province on Honshū, at the beginning of the 8th century. At first, the province was a single gun (district), but was later divided into three gun: Sawata, Hamochi and Kamo.

In 1185, the designated representative Shugo for Sado, Osaragi, appointed Honma Yoshihisa as his shugodai (delegate) for the province.

The rule of the Honma clan on Sado lasted until Uesugi Kagekatsu took control of the island in 1589. After the defeat of the Uesugi at Sekigahara, and the discovery of gold on the island, the shogunate took direct control of the island.

The island was for a short time an independent prefecture, called the Aikawa prefecture, between 1871 and 1876, during the Meiji era. It then became a part of Niigata Prefecture, which it is still as of today.

At the end of the 19th century, there were three districts (郡), seven towns (町), and 51 villages (村). During the 20th century, a series of mergers steadily reduced the number of political local authorities, following the recent trend in Japan to cut the costs of having separately run local administrations. The current city (市) covering the whole island was established on March 1, 2004 from a merger of all remaining municipalities on the island: the city of Ryōtsu: the towns of Aikawa, Kanai, Sawata, Hatano, Mano, Hamochi and Ogi; and the villages of Niibo, and Akadomari (all from Sado District).

10 subdivisions (former municipalities) in the Sado City

10 subdivisions (former municipalities) in the Sado City

Exile in Sado

When direct control from mainland Japan started around the 8th century, the island's remoteness meant that it soon became a place of banishment for difficult or inconvenient Japanese figures. Exile to remote locations such as Sado was a very serious punishment, second only to the death penalty, and people were not expected to return.

The earliest known dissident to be condemned to exile on Sadogashima was a poet, Hozumi no Asomi Oyu (穂積朝臣老). He was sent to the island in 722, reportedly for having criticized the emperor.

The former Emperor Juntoku was sent to Sado after his role in the Jōkyū War of 1221. The disgraced emperor survived twenty years on the island before his death; and because he was sent to Sado, this emperor is known posthumously as Sado-no-in (佐渡院). He is buried in the Mano Goryo mausoleum on the west coast.[1]

The Buddhist monk Nichiren lived on Sado close to the present village Niibo in Kuninaka Plain from 1271 to 1274. In the 17th century, Konpon Ji Temple was built at the place where he lived. At the end of his exile, Nichiren lived at the place where Myosho Ji temple was built later. He used to meditate at the place where Jisso Ji Temple can be visited today. In addition, Nipponzan Myohoji, a modern Nichiren Buddhist order, established a Peace Pagoda in the city to help in inspiring people toward world peace.

The Noh dramatist Zeami Motokiyo was exiled on unspecified charges in 1434.

The last banishment in Sado took place in 1700, almost a millennium after the first.

Gold mine

Sado experienced a sudden economic boom during the Edo period when gold was found in 1601 at Aikawa (相川). A major source of revenue for the Tokugawa shogunate, the mines were worked in very severe conditions.

A manpower shortage led to a second wave of "exiles" coming to Sado, although this time it was not imposed as a sentence for a committed crime. By sending homeless people (the number of whom was growing in Japanese cities at the time) to Sado from the 18th century, the Shogunate hoped to kill two birds with one stone. The homeless were sent as water collectors and worked in extremely hard conditions, with a short life expectancy. The Sado mine at its peak in the Edo era produced around 400 kilograms (1,100 troy pounds) of gold a year (as well as some silver). The small settlement of Aikawa quickly reached a population of around 100,000. The mine closed in 1989.

External influence on Sado culture

In feudal Japan, when the Nishimawari naval route was opened in 1672, Ogi (in the South of the Island) became a main stop on this major naval route in the Sea of Japan between the Kansai area and northern areas of the archipelago.

Exiles and shipping in old times both had a major influence on Sado's cultural background. The island is for instance dotted with Noh theaters, and the local Japanese dialect and accent are different from those of Niigata.

Emergency landing on Sado

A few months after World War II, on 18 January 1946, a Douglas Dakota (C-47) Sister Ann in British RAF service made an emergency landing on the island.[2] The locals helped in the recovery and building a runway for it to depart, the story of which was made into a film named Tobe! Dakota (Fly, Dakota, Fly!)[3] with the film's Dakota made into an island exhibit.[4] The story of the events leading up to the crash were also made into a film, The Night My Number Came Up.

Geography

The island consists of two parallel mountain ranges running roughly southwest–northeast, enclosing a central plain. The Ōsado (大佐渡) range, in the north, is slightly higher, with peaks of Mount Kinpoku (金北山), the highest point of the island at 1,172 metres (3,845 ft), Mount Kongō, Mount Myōken, and Mount Donden. Kosado (小佐渡) range in the south faces the Honshu coast. The highest point in Kosado is Ōjiyama (大地山) at 645 m.

The plain in between is called Kuninaka (国中) and is the most populated area. The Kuninaka plain opens on its eastern side onto Ryōtsu Bay (両津湾), and on its western side onto Mano Bay (真野湾), where the longest river, Kokufugawa (国府川, also read Konogawa) reaches the sea.

The island has a symmetrical shape. Lake Kamo (加茂湖), on the eastern side of Kuninaka, is filled with salt water, and is a growing place for oysters.

Sado island

Sado island View of the coast of Sado

View of the coast of Sado

Climate

Sado has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) with potentially hot, humid summers and cold winters. Precipitation is quite heavy throughout the year.

| Climate data for Aikawa, Sado, Niigata, 1991−2020 normals, extremes 1911−present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.0 (62.6) |

20.7 (69.3) |

22.3 (72.1) |

28.0 (82.4) |

30.0 (86.0) |

34.1 (93.4) |

37.4 (99.3) |

38.5 (101.3) |

37.4 (99.3) |

31.5 (88.7) |

26.3 (79.3) |

22.9 (73.2) |

38.5 (101.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.6 (49.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

19.9 (67.8) |

23.3 (73.9) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.3 (84.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

9.7 (49.5) |

17.4 (63.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.0 (39.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.5 (43.7) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.9 (60.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

22.5 (72.5) |

17.2 (63.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

6.8 (44.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.9 (37.2) |

7.2 (45.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

16.6 (61.9) |

21.3 (70.3) |

22.9 (73.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

8.2 (46.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

10.8 (51.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.5 (18.5) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

9.5 (49.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 131.1 (5.16) |

91.6 (3.61) |

96.6 (3.80) |

94.5 (3.72) |

97.3 (3.83) |

122.5 (4.82) |

207.3 (8.16) |

137.5 (5.41) |

139.9 (5.51) |

133.1 (5.24) |

154.8 (6.09) |

175.7 (6.92) |

1,581.9 (62.27) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 28 (11) |

25 (9.8) |

4 (1.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

9 (3.5) |

66 (25.9) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 3 mm) | 19.7 | 15.3 | 14.0 | 10.3 | 9.7 | 9.0 | 10.9 | 8.7 | 10.4 | 12.3 | 16.6 | 20.9 | 157.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1 cm) | 7.1 | 6.8 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 17.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69 | 68 | 66 | 67 | 72 | 78 | 81 | 77 | 73 | 69 | 68 | 69 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 46.2 | 69.2 | 133.1 | 177.0 | 200.7 | 178.4 | 161.2 | 207.8 | 157.0 | 147.5 | 95.8 | 50.6 | 1,624.5 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[5][6] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Per Japanese census data,[7] the population of Sado peaked around 1950 and has declined by roughly 60 percent in the decades since.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 107,351 | — |

| 1930 | 106,262 | −1.0% |

| 1940 | 109,016 | +2.6% |

| 1950 | 125,597 | +15.2% |

| 1960 | 113,296 | −9.8% |

| 1970 | 92,558 | −18.3% |

| 1980 | 84,992 | −8.2% |

| 1990 | 78,061 | −8.2% |

| 2000 | 72,173 | −7.5% |

| 2010 | 62,727 | −13.1% |

| 2020 | 51,492 | −17.9% |

Today

Economy

As of May 1, 2017, the island has an estimated population of 55,474. The island of Sado has seen a steady decline in population since 1950 when the population was 125,597. Similar trends have been common in other remote locations of Japan since World War II as younger generations have moved to more urban areas. As of October 1, 2008, 36.3% of the island population is over 65 years old, which is a larger ratio than the national average. Over 65 is the only increasing age demographic. The island is now less populated than it was in the 18th and 19th century. There is no university, and the options for post high school studies, short of leaving and going to the mainland, are limited to a few specialty schools.

Agriculture and fishing are major sources of income for Sado. According to the 2000 national census, 22.3% of the workforce was employed in the primary sector and 25% in the secondary sector. Fishing is mainly based in Ryotsu and Aikawa.

Tourism boomed in the beginning of the 1990s and peaked at over 1.2 million yearly visitors, but visitor numbers decreased over the 1990s. In the mid-2000s, the number of visitors was closer to 650,000 per year.

Sado is known for a number of Japanese bamboo weaving artists and artisans who are renowned throughout the country.[8][9][10]

Tourism

Its rich history and relaxed rural atmosphere make Sado one of the major tourist destinations in Niigata Prefecture. The island has several temples and historical ruins, and offers possibilities for various outdoor activities, as well as fresh local food.

Sado is famous as the major breeding area for the Japanese crested ibis. The last known Japan-born Japanese crested ibis died in captivity in 2003 on the island. Currently, birds from China are being bred in a captive program in a facility in Niibo area, and have been released since 2008. The first hatchings in the wild were observed in April 2012. The ibis is a major symbol of the Island and can be found on several tourist items. As of June 2022, approximately 480 crested ibis have been observed making a radical comeback for their species, thanks to conservation efforts.[11]

There are many small local traditional festivals, and since 1988 a major yearly arts festival, called the Earth Celebration, has been run by the taiko group Kodo. The group lives on the island, touring eight months a year, and in August they invite international artists to collaborate with them at their festival on Sado. Tickets are limited for the three-day weekend event. In recent years, Kodo has made a solo performance on the Friday evening; the festival's invited act plays Saturday night; and Sunday concludes with a joint performance with Kodo and guests.

The Sado tourism industry suffered direct (though limited) as well as indirect damage from the 2004 Chūetsu earthquake, as access routes inside Niigata Prefecture were cut.

Sights

Sado has a large variety of sights to offer.

- Myōsen-ji is a temple with a five-storied pagoda a few kilometers east of Mano. The pagoda was built by two generations of carpenters and took 30 years to complete in 1825.[12]

- Konpon-ji Temple in the village of Niibo in the middle of the island was built in the 17th century at the very place where Nichiren lived at first during his exile on Sadogashima.

- Rengebuji Temple near Ogi, housing several buildings classified as important cultural properties.

- For two years, Nichiren lived at the place where Myōshō-ji Temple can be visited today. The temple which has a beautiful garden is northeast of the town of Sawata. Jisso-ji Temple which is visited by many pilgrims is close by. It was built at a place where Nichiren used to meditate. The pine tree where he used to hang his clothes can still be seen today.[13] A tall Nichiren Memorial was erected close to the temple.

- The Art and Natural History Museum of Sado is on the west coast between Sawata and Mano. Some reconstructed pile houses can be seen in its garden. Originally, the inhabitants of Sado lived in pile houses.

- A traditional wooden Noh Theatre which was built in the 19th century can be visited near Daizen Shrine in the east of Mano.

- Shukunegi is a historically preserved ward which has existed since the Edo Era as a Sado port town. The streets brimming over with atmosphere and built by shipwrights are splendid.[14]

A crested ibis nearby the Crested Ibis Conservation Center on Sado Island

A crested ibis nearby the Crested Ibis Conservation Center on Sado Island Myōsen-ji Temple

Myōsen-ji Temple Konpon-ji Temple

Konpon-ji Temple.jpeg.webp) Noh theatre

Noh theatre Reconstruction of the Sado bugyōsho

Reconstruction of the Sado bugyōsho Senkakuwan

Senkakuwan Himezaki lighthouse

Himezaki lighthouse

Transportation

.png.webp)

Ship

Sado Steam Ship operates two routes connecting to the mainland.

Bus

Transit bus network all over the island is operated by Niigata Kotsu Kanko Bus.

Air

Kyokushin Airways, operating the route to Niigata, ceased its operations in September 2008. New Japan Aviation operated three or four flights daily to Sado Airport, but service to the airport was suspended indefinitely in April 2014.[15]

Notable people

- Ikki Kita (北 一輝 Kita Ikki, 1883 – 1937); real name: Kita Terujirō (北 輝次郎)), Japanese author, intellectual and political philosopher active in early-Shōwa period.

- Hachirō Arita (有田 八郎, 1884–1965), a Japanese politician and diplomat who served as the Minister for Foreign Affairs for three terms. He is believed to have originated the concept of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

- Charles Robert Jenkins (1940–2017), former United States Army sergeant who deserted to North Korea in 1965 where he was detained until 2004. He lived on Sado with his Japanese wife Hitomi Soga, an abductee he met in North Korea.[16]

- Makoto Asashima (浅島 誠, born 1944), biologist[17]

- Hideyo Hanazumi (b. 1958), politician and Governor of Niigata Prefecture.

- Hitomi Nabatame (b. 1976), actress and singer.

- Aka Akasaka (b. 1988), manga artist and writer.

See also

References

- ↑ Bornoff, Nicholas. (2005). National Geographic Traveler Japan, p. 193.

- ↑ Powell, Dennis M (9 August 1957). "Correspondence". Flight and Aircraft Engineer. 72 (2533): 204. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ↑ Fly, Dakota, Fly! at IMDb

- ↑ Harano, Jōji (2 October 2013). "The True Story of the Downed Dakota: Sado Islanders Come Together to Help Create 'Fly, Dakota, Fly!'". nippon.com. Nippon Communications Foundation. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ↑ "Aikawa Climate Normals 1991-2020". JMA. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Aikawa Climate Extremes". JMA. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ↑ Sado population statistics

- ↑ "Honma Hideaki | Flowing Pattern | Japan | Heisei period (1989–present) | the Met". www.metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ↑ "Kagedo Japanese Art Bamboo Sculpture by Honma Hideaki, Nitten Exhibition 2011 - Kagedo Japanese Art". kagedo.com. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ "Kosuge Kōgetsu | Flower Basket (Hineri-gumi hanakago) | Japan | Shōwa period (1926–89)". Archived from the original on 2017-10-05.

- ↑ "In Japan, a real-life phoenix rises from the ashes of extinction".

- ↑ Shobunsha Publications: Niigata to Sadogashima, p. 241. Tokyo 2002. ISBN 4-398-14261-4

- ↑ Shobunsha Publications: Niigata to Sadogashima, p. 243. Tokyo 2002. ISBN 4-398-14261-4

- ↑ "About Shukunegi - Sado Travel Guide | Planetyze". Planetyze. Retrieved 2017-11-02.

- ↑ "新潟県:佐渡空港". Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ Glionna, John M. (16 July 2009). "Second life of GI who deserted to North Korea". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ 変わらない熱情で、中胚葉へと変わる過程を見る. Science Library Special (in Japanese). JT Biohistory Research Hall. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

Bibliography

- Bornoff, Nicholas (2005). National Geographic Traveler Japan (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 0-7922-3894-X. OCLC 60860593.

External links

Sado Island travel guide from Wikivoyage

Sado Island travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official Website (in Japanese)

- Sado Tourism Association Website (in English)