North American Phalanx | |

Formerly listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

One of two primary residential edifices of the North American Phalanx as it appeared in August 1972, shortly before its destruction by fire | |

| Location | Phalanx Rd. |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 72001499[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | 1972 |

| Removed from NRHP | 1974 |

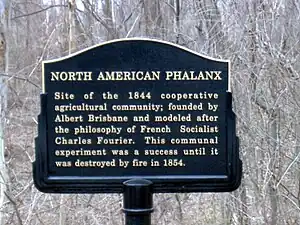

The North American Phalanx was a secular utopian socialist commune located in Colts Neck Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey. The community was the longest-lived of about 30 Fourierist Associations in the United States which emerged during a brief burst of popularity during the decade of the 1840s.

The North American Phalanx was established in September 1843 and included the active participation of writer Albert Brisbane and newspaper publisher Horace Greeley, two of the leading figures of the Fourierist movement. The Association was disbanded in January 1856, following a catastrophic fire which destroyed a number of the community's productive enterprises. At the time of its termination it was the last of about 30 Fourierist Associations established during the 1840s still in existence and thus was the longest-lived.

The main residential dwelling of the phalanx, a three-story wooden structure, stood vacant until it was itself destroyed by fire in November 1972.

History

Background

Charles Fourier (1772–1837) was a French philosopher who believed that the structure of modern civilization led to poverty, unemployment, isolation, and unhappiness and that people would be better off living in organized communal societies rather than individual family units. Fourier developed the idea of the phalanstère, a collectively dwelling and cooperatively working community of 1,620 people organized on the basis of a joint stock company.

While never pursued in France during his lifetime, Fourier's ideas found practical realization in the United States in the 1840s and early 1850s as a result of the books and newspaper columns of Albert Brisbane (1809–1890). It was Brisbane who translated, distilled, and adapted Fourier's ideas for an American audience, largely through the pages of Horace Greeley's New York Tribune, stirring popular enthusiasm for the French intellectual's ideas for the formation of local associations, known as "phalanxes."

Early in 1843 a general call was issued in New York City by Brisbane, Greeley, and others, seeking local organizations of Fourierist groups.[2] This call inspired the formation in the summer of 1843 of a group calling itself the Albany Branch of the North American Phalanx.[2] About 20 families participated in the official planning of the group, of which about a dozen families formally subscribed to the draft constitution,[2] on August 12, 1843.[3]

It was believed by the first participants that considerable capital would be raised for establishment of an American cooperative association and that a number of other branch organizations would emerge throughout the New York region, inspired by the Albany group's activity and success.[2] Neither of these expectations were realized, however, as it was only with great difficulty that a sum just under $7,000 was raised and no other local associations would immediately follow.[2] Moreover, a majority of the phalanx's financing came from outside sources, as over time 61% of the association's stock would be held by outsiders, including 527 shares held by a sympathetic consortium of merchants from New York City.[4]

Despite clearly inadequate resources, the Albany Branch, headed by Charles Sears and Nathan Starks, decided to persevere and a search began for suitable agricultural lands upon which a local phalanstery might be established.

Establishment

A domain of 673 acres (2.72 km2) was located near the small town of Red Bank, New Jersey, priced at $14,000.[5] Of this sum $5,000 of the community's funds were invested as a down payment, leaving a mortgage of $9,000 to be repaid over time.[5] Barely $2,000 remained for the construction of buildings and the purchase of working animals, farm implements, and other necessary goods.[5]

Colonization began in September 1843, with six families crowded into two houses previously existing on the property.[5] Temporary housing was rapidly constructed to provide accommodations for the rest of the party that winter.[5]

Others arrived at the site in the spring of 1844, with a total of 100 people as part of 20 families in residence by the end of that year.[5] At its peak the community would eventually count about 150 people in residence, including children, usually ranging between 120 and that number.[5]

After one year of existence a saw-mill had been constructed and was nearly ready for operation, and a blacksmith shop and a machine shop powered by a steam engine were already operational.[6] In addition, the community included stables, animal and wagon sheds, carpentry shops, a school and children's day care area, guest cottages, landscaped gardens and paths, and an artificial pond for bathing, boating and a supply of ice in the winter.[7]

Most of the household heads living in the North American Phalanx at the time of its formation had either passing or practical knowledge of agriculture.[5] The land was deemed quite suitable for fruit farming and a good percentage of the available land was subsequently committed to fruit trees, including apples, peaches, pears, and quince.[5] In addition grape vines were planted.[5]

In 1847 a new three-story addition was constructed, adding common area. Together with a pair of long halls, the phalanx subsequently had housing sufficient for each family to be allotted a parlor and two bedrooms.[8] A 70-foot long restaurant was also constructed at the same time.

The North American Phalanx was moderately successful during its first seven years of operation, paying annual dividends ranging from 4.4% to 5.6% on capital invested, as well as hourly wages to all workers of the community.[9]

Labor and compensation

In accordance with the Fourierian scheme, labor was divided into general departments, called "series," of which there were six at the North American Phalanx: agriculture, livestock, manufacturing, domestic work, education, and "festal" (entertainment).[10] Within each of these there were additional subdivisions called "groups," consisting of 3 to 7 people, who would work cooperatively on specific given tasks.[10] For example, the agricultural series included four groups: farming, market gardening, orchard, and experimental.[10] Additional groups not associated with any series were formed for performance of special "repugnant" work and the care of visitors.[11]

Each of these groups elected a chief, who kept track of labor time and who represented it at meetings with other group chiefs at meetings of the department, called the "council."[10] Council members in turn elected a chief, who served as general manager of the department and presiding officer at meetings of the council.[10] These general managers each met daily as part of a body called the Industrial Council, which determined jobs needing to be done the following day.[12]

Domestic work was performed by women, with the organized subdivision of domestic tasks practiced in accordance with the model used for other series.[12]

At the end of each year, proceeds of the year's production would be calculated and — in accordance with the Fourierian scheme — awards for capital, labor, and talent allocated. By way of example, rates of 5% on capital invested and $1 per ten-hour day for "ordinary" labor were in force at the end of the North American Phalanx's existence.[13] Jobs were compensated at three levels, with exhausting or repugnant jobs earning a premium and light and attractive jobs being docked a penalty.[13] In addition bonuses were awarded or demerits assessed for the excellence or lack of skill of performance.[13]

Each group rated its own members for purposes of compensation, with labor performance rather than age or gender the determining factor in setting wage rates.[13]

While the community initially attempted to make payment to its members in cash, with money tied up in land and property and the supply of paper money erratic, a move to the issuance of scrip was soon made.[14] This "house currency" was of the same general size and appearance as regular paper money of the day, but featured a central bust of Charles Fourier.[15] Wages and assessments for room and board were made monthly, with scrip used as tender to settle the balances of all such accounts.[15]

Daily life

Collective living and rational division of domestic responsibility was a primary tenet of Fourierism. During its first two or three years of existence, extreme frugality was deemed necessary, and only "scanty" meals were served at the common table.[16] The situation was further complicated by the presence of significant numbers of associationists with specific dietary beliefs, including contingents of vegetarians and Christian sectarians who foreswore the use of all products produced at the cost of a sacrifice of life.[16] The effect was disruptive, with the moderate and extreme vegetarians agitating against the slaughter of animals and the consumption of meat.[17]

The dietary dilemma was ultimately resolved by the replacement of the common table with a restaurant; board was provided on an à la carte basis rather than through a common menu.[17] Another benefit was that food waste was reduced, according to North American Phalanx president Charles Sears.[17]

Just as there was difference in eating habits, a range of religious affiliations existed among the North American Phalanx's resident members. Included among the community's ranks were Unitarians, Presbyterians, Quakers, Baptists, Episcopalians, Jews, Shakers, as well as agnostics and atheists.[18] While religious matters were frequently the object of discussion and debate, heated division over religious topics does not seem to have occurred in the community until 1853, with the climate sharpening as the end of the institution approached.[18]

The phalanx maintained a nursery for younger children as well as a school for older children, the combination of which served to significantly reduce the domestic duties of female members.[19] Efforts were made to build an appreciation for collectivist ideals in the minds of the community's 30 to 40 children, with children and youth encouraged to work cooperatively in organizing amusements, forest expeditions, camping trips, and craft projects.[19]

Community entertainment was more formally organized in 1849 with the formation of a "festal series" in charge of staging musical concerts, dramatic presentations, and dances.[20] In addition, the community had a vibrant informal social atmosphere, with nightly walks in the woods, card games, and singing around the piano.[20] Members read Greeley's New York Tribune and other newspapers, agricultural publications, and maintained a reading room.[21] A steady stream of visitors infused new ideas and earnest discussions into the small rural society.[21] The atmosphere of the North American Phalanx and other Fourierist Associations which survived more than a year or two resembled that of a vibrant New England farming village, it was later reckoned.[21]

Governance

The phalanx's 1843 constitution provided for administration through a central council, composed of a president, vice-president, treasurer, and 12 directors, with the executive officers serving one year terms and the council members serving staggered two year terms. Originally, only stockholders voted in elections for the council, but all members were given a vote in an 1848 amendment. Heads of each series were granted ex officio status as members of the central council.[12]

Suffrage was universal both industrially and politically, with any regular working member of a group entitled to vote within that group without regard to gender.[22]

Decline

The North American Phalanx, like the Fourierist movement in general, was ultimately undermined by its utopian basis — a general creed which as one scholar observed "promised too much and required too little of its adherents."[23] The disparity between promises of social transformation and economic abundance and the realities of primitive agriculture and crude living conditions ended with the disillusionment of starry-eyed communitarians and their inflated expectations.[23] Work was hard, the process of development slow and difficult, and communal life in close quarters presented a whole host of social pressures which undermined community stability.[23]

The Fourierist model of labor division and wage calculation also proved inefficient in practice, with president Charles Sears noting that members of the North American Phalanx were so preoccupied with work allocation and scheduling that "our days were spent in labor and our nights in legislation" — a regimen which sapped the vitality of the community.[24] The community's unity was also undermined by an inequality of workloads and compensation, as Carl Guarneri has observed:

"For Fourier, the notion that some Harmonians would work less than others demonstrated true passional freedom; life in the American phalanxes, however, required hard work and self-sacrifice. As their communities struggled through indebtedness, chronic shortages, and crop failures, Associationists found themselves undermined by their own propaganda. ... The phalanxes never solved the problem of what to do about those who did not assume their share of the work."[25]

Wage rates were another source of discord, with machine operators formally complaining in 1853 that their wages paid as members of the phalanx ran significantly behind wages paid for comparable work in competitive industry outside the association.[17] Moreover, the wages paid to working members of the phalanx proved barely adequate to cover room, board, and clothing for families with children — causing the loss of many of the same and the undermining of hopes of passing the community to a new generation.[26]

The North American Phalanx was also hard hit by the loss of its chief carpenter, a skilled horticulturalist, and other leading members in an 1853 succession to join the fledgling Raritan Bay Union.[27] In short order Raritan Bay members and financial supporters owned fully one-sixth of the North American Phalanx's stock, further weakening the older phalanx's resolve to continue.[28]

Dissolution

Disaster came on September 10, 1854, when a fire swept the colony's mill and all its contents.[29] No insurance was recovered, and the community found itself facing $30,000 in accumulated debt with no ready means of repayment.[29] Of this, some $9,000 remained unpaid on the original mortgage, with additional bills accumulated for a new engine and boiler for the mill.[30] Additionally, at the time of the fire the mill had housed a large quantity of wheat purchased on credit, for which the phalanx was financially responsible.

While Horace Greeley offered to loan the association $12,000 for construction of a replacement facility,[31] members of the phalanx ultimately decided not to take advantage of this offer, which would have boosted the debt load and necessitated another arduous reconstruction period.[29] Instead, starting with the January 1855 stockholders' meeting, plans began to be made either to sell part of the phalanx's land to satisfy debt or to sell the community in whole.[32] Efforts were made to sell the phalanx to a group organizing around Fourierist adherent Victor Considerant to act as a staging point for newcomers to his new colonization project in the state of Texas.[32] No such agreement could be reached however.[32]

Instead in June 1855 the stockholders voted that the community should liquidate its assets and terminate its existence.[30] In October community land was surveyed and divided into parcels ranging in size from 5 to 150 acres and sold at auction, together with all movable property.[30] A total of $80,000 was raised from the sale of the North American Phalanx's land and property,[29] with the proceeds divided and disbursed to the stockholders, who received 57.33 cents per dollar invested in the liquidation.[30]

In January 1856 the North American Phalanx — the sole survivor of the Fourierist boom of the 1840s — was formally terminated.[33]

Legacy

The North American Phalanx was the second most publicized association of the 1840s Fourierist movement, surpassed in general interest only by Brook Farm in West Roxbury, Massachusetts.[3]

The main edifice of the North American Phalanx stood until November 1972 when it was destroyed in another fire. At present, two structures – both private homes – from the original Phalanx property survive. One of them, constructed around 1851, was the cottage of Marcus Spring, a merchant from Brooklyn, New York, who was a supporter of the Phalanx. He and his family used the cottage as their summer home. Although Mr. Spring was not a resident member of the Phalanx, he was one of its largest shareholders, having invested, with several New York colleagues, over $50,000 in the endeavor.

The Monmouth County Historical Association in Freehold Borough, New Jersey houses a collection of records of the North American Archive which include legal and financial documents, meeting minutes, miscellaneous manuscripts, published material about the phalanx, photographs and illustrations, maps, drawings, and blueprints.[7] The collection contains a total of 148 items and occupies 2 linear feet of shelf space and is open for use by researchers without restriction.[7] c;

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Charles Sears, The North American Phalanx: An Historical and Descriptive Sketch. Prescott, WI: John M. Pryse, 1886; pg. 3. The Sears history of the North American Phalanx appears to have been prepared in December 1852 at the request of pioneer historian of the cooperative movement A.J. Macdonald with a subsequent amendment describing termination of the enterprise. See: Noyes, History of American Socialisms, pg. 450.

- 1 2 William Alfred Hinds, American Communities and Co-operative Colonies, Second Edition. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1908; pg. 266.

- ↑ Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 173.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sears, The North American Phalanx, pg. 4.

- ↑ Letter to the Convention of Associations, published in The Phalanx, Dec. 9, 1844. Reprinted in Hinds, American Communities and Co-operative Colonies, pp. 266-267.

- 1 2 3 Lois R. Densky and Gregory J. Plunges, "North American Phalanx Records, 1841-1972," Archived 2008-10-05 at the Wayback Machine Monmouth County Historical Association, Library and Archives Manuscript Collections, Collection 5, May 1980.

- ↑ Hinds, American Communities and Co-operative Colonies, pg. 267.

- ↑ Hinds, American Communities and Co-operative Colonies, pg. 273.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sears, The North American Phalanx, pg. 5.

- ↑ Sears, The North American Phalanx, pp. 5-6.

- 1 2 3 Sears, The North American Phalanx, pg. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Sears, The North American Phalanx, pg. 7.

- ↑ Sears, The North American Phalanx, pp. 7-8.

- 1 2 Sears, The North American Phalanx, pg. 8.

- 1 2 Sears, The North American Phalanx, pg. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 Sears, The North American Phalanx, pg. 11.

- 1 2 Sears, The North American Phalanx, pg. 12.

- 1 2 Sears, The North American Phalanx, pg. 15.

- 1 2 Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 215.

- 1 2 3 Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 214.

- ↑ Sears, The North American Phalanx, pp. 6-7.

- 1 2 3 Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 175.

- ↑ Quoted in John Humphrey Noyes, History of American Socialisms. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1880; pg. 454.

- ↑ Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 195.

- ↑ Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 322.

- ↑ Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pp. 325-326.

- ↑ Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 326.

- 1 2 3 4 Sears, The North American Phalanx, pg. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 Sears, The North American Phalanx, pg. 18.

- ↑ Hinds, American Communities and Co-operative Colonies, pg. 274.

- 1 2 3 Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 327.

- ↑ Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative, pg. 321.

Further reading

- Herman J. Belz, The North American Phalanx: An Experiment in Fourierist Socialism, 1843-1855. PhD dissertation. Princeton University, 1959.

- Herman Belz, "The North American Phalanx: An Experiment in Socialism," Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, vol. 81 (Oct. 1963), pp. 215–247.

- Albert Brisbane, Social Destiny of Man, or, Association and Reorganization of Industry. Philadelphia, PA: C.F. Stollmeyer, 1840.

- Albert Brisbane, A Concise Exposition of the Doctrine of Association, or, Plan for a Re-organization of Society: Which Will Secure to the Human Race, Individually and Collectively, Their Happiness and Elevation. New York: J.S. Redfield, 1843.

- William Alfred Hinds, American Communities and Co-operative Colonies, Second Edition. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Co., 1908.

- George Kirchmann, "Why Did They Stay? Communal Life at the North American Phalanx," in Paul A. Stellhorn (ed.), Planned and Utopian Experiments: Four New Jersey Towns: Papers Presented at the Tenth Annual New Jersey History Symposium, December 2, 1978. Trenton, NJ: New Jersey Historical Commission, 1980; pp. 10–27.

- George Kirchmann, "Unsettled Utopias: The North American Phalanx and the Raritan Bay Union," New Jersey History, vol. 97 (Spring 1979), pp. 25–36.

- John Humphrey Noyes, History of American Socialisms. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1880.

- Charles Sears, The North American Phalanx: An Historical and Descriptive Sketch. Prescott, WI: John M. Pryse, 1886.

- Thomas A. Shiels, The North American Phalanx. PhD dissertation. Salisbury University, 2007.

- Eric R. Schirber, The North American Phalanx. MA thesis. Trinity College, 1972.

- Jayme A. Sokolow, The North American Phalanx (1843-1855): A Nineteenth-century Utopian Community. Edwin Mellen Press, 2009.

- Edward K. Spann, Brotherly Tomorrows: Movements for a Cooperative Society in America, 1820-1920. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988.

- Norma Lippincott Swan, "The North American Phalanx," Monmouth County Historical Society Bulletin, vol. 1 (May 1935), pp. 35–63.

- Harold F. Wilson, "The North American Phalanx: An Experiment in Communal Living," Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, vol. 70 (July 1952), pp. 188–209.

- Kalikst Wolski, "A Visit to the North American Phalanx," Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, vol. 70 (July 1952), pp. 188–209.149-160.

External links

Media related to North American Phalanx at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to North American Phalanx at Wikimedia Commons- Lois R. Densky and Gregory J. Plunges, "North American Phalanx Records, 1841-1972," Monmouth County Historical Association, Library and Archives Manuscript Collections, Collection 5, May 1980.