| History of Germany |

|---|

|

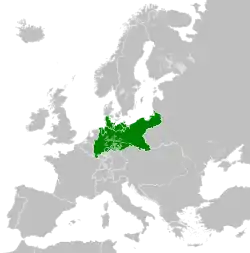

The North German Confederation (German: ⓘ)[1] was initially a German military alliance established in August 1866 under the leadership of the Kingdom of Prussia, which was transformed in the subsequent year into a confederated state (a de facto federal state) that existed from July 1867 to December 1870. A milestone of the German Unification, it was the earliest continual legal predecessor of the modern German nation-state known today as the Federal Republic of Germany.[2]

The Confederation came into existence following the Prussian victory in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 over the lordship of two small Danish duchies (Schleswig-Holstein) resulting in the Peace of Prague, where Prussia pressured Austria and its allies into accepting the dissolution of the existing German Confederation (an association of German states under the leadership of the Austrian Empire), thus paving the way for the Lesser German version of German unification in the form of a federal state in Northern Germany. Construction of such state became a reality in August 1866, following the North German Confederation Treaty, initially as a military alliance only, while its first federal constitution establishing a constitutional monarchy with the Prussian king holding as the head of state the Bundespräsidium was adopted on 1 July 1867.[3] Laws could only be enabled with the consent of the Reichstag (a parliament based on universal male suffrage) and the Federal Council (Bundesrath, a representation of the states). During the initial three and a half years of the Confederation, a conservative-liberal cooperation undertook important steps to unify (Northern) Germany with regard to law and infrastructure. The designed political system and the political parties remained essentially the same also after 1870.

Shortly after its inception, tensions emerged between the North German Confederation and the Second French Empire, which was ruled by the French Emperor Napoleon III. In Summer 1870, a dispute over a new king for Spain escalated into the Franco-Prussian War. At the time, the original Confederation had nearly 30 million inhabitants of whom 80% lived in Prussia, thus making up roughly 75% of the population of the future German Empire. Under these circumstances, the South German states of Baden, Hesse-Darmstadt, Württemberg and Bavaria previously opposed to the Confederation ultimately decided to join it.[4] A new short-lived constitution subsequently entered into force on 1 January 1871 proclaiming in its preamble and article 11 the "German Empire" despite being titled as one of a new "German Confederation", but it lasted only four months. Following the victory in the war with France, the German princes and senior military commanders proclaimed Wilhelm "German Emperor" in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles.[5] Transition from the Confederation to the Empire was completed when the Constitution of the German Empire which prevailed until the demise of the monarchy entered into force on 4 May 1871, while France recognised the empire on 10 May 1871 in the Treaty of Frankfurt.[6][7]

Prelude

For most of 1815–1833, Austria and Prussia worked together and used the German Confederation as a tool to suppress liberal and national ambitions in the German population.

Zollverein

The first major step towards a Lesser German solution was the Zollverein, a customs union formed by the treaties of 1833, with Prussia being the primary driver behind the customs union.[8] Although it was formally inaugurated on 1 January 1834, its origins may be traced to a variety of custom unions among the German states, formed beginning from 1818. The Zollverein was not subordinate to the Austrian-led German Confederation (1815–1866) and Austria itself was excluded because of its highly protectionist trade policy, the unwillingness to split its customs territory into the separate Austrian, Hungarian and Galician-Lodomerian ones, as well as due to opposition of Prince von Metternich to the idea.[9] Nevertheless, the Zollverein managed to include by 1866 the majority of the German states.[10]

Frankfurt Parliament and the Erfurt Union

In 1849, the National Assembly in Frankfurt elected the Prussian king as the Emperor of a Lesser Germany (a Germany without Austria). The king refused and tried to unite Germany with the Erfurt Union of 1849–1850. When the union parliament met in early 1850 to discuss the constitution, the participating states were mainly only those in Northern and Central Germany. Austria and the southern German states Württemberg and Bavaria forced Prussia to give up its union plans in late 1850.[11]

In April and June 1866, Prussia proposed a Lesser Germany again. A corner stone of the proposal was the election of a German parliament based on universal male suffrage.[12] The proposal explicitly mentioned the Frankfurt election law of 1849. Otto von Bismarck, the minister-president of Prussia, wanted to gain sympathy within the national and liberal movement of the time. Austria and its allies refused the proposal. In summer 1866 Austria and Prussia fought with their respective allies in the Austro-Prussian War.

Peace of Prague and dissolution of German Confederation

Prussia and Austria signed a Nikolsburg preliminary (26 July) and a final peace treaty of Prague (23 August). Austria accepted the Prussian demand for the German Confederation to be dissolved. Prussia was allowed to create instead a "closer federation" (einen engeren Bund) in Germany north of the river Main. Bismarck had already agreed on this limitation with the French emperor Napoleon III prior to the peace talks.[13]

Formation of the North German Confederation

Military alliance

On 18 August 1866, Prussia and a larger number of North and Central German states signed the North German Confederation Treaty establishing a Bündniß (alliance). The treaty created a military alliance for one year. It also affirmed that the states wanted to form a federal state based on the Prussian proposals of June 1866. They agreed to have a parliament elected to discuss a draft constitution. At the same time, the original East Prussian craddle of the Prussian statehood as well as the Prussian-held Polish- or Kashubian-speaking territories of Province of Posen and West Prussia were formally ′annexed into Germany. Saxony and Hesse-Darmstadt, former enemies in the war of 1866, had to agree their accession to the new federation in their respective peace treaties (Hesse-Darmstadt only joined with its northern province, Upper Hesse).[14] Later in 1866, other states joined the treaty. The liberals in the Prussian parliament favored a wholesale annexation of all North German territories by Prussia. In a similar way, Sardinia–Piedmont had created the Kingdom of Italy. But Bismarck chose a different approach. Prussia incorporated (in October 1866) only the former military opponents Hannover, Hesse-Kassel, Nassau, the free city of Frankfurt, and the Hesse-Homburg area of Hesse Darmstadt. These areas were combined into the two new Prussian provinces of Hannover and Hesse-Nassau. Schleswig and Holstein also became a Prussian province.[15]

Towards a federal constitution

Bismarck sought advice from conservative and democratic politicians and finally presented a draft constitution to the other state governments. At the same time, in late 1866, Prussia and the other states prepared the election of a North German parliament. This konstituierender Reichstag was elected in February 1867 based on state laws. The konstituierender Reichstag gathered from February to April. In close talks with Bismarck, it altered the draft constitution in some significant points. The konstituierender Reichstag was not a parliament but only an organ to discuss and accept the draft constitution. After that, the state parliaments (June 1867) ratified it so that on 1 July the constitution was enabled. In August, the first Reichstag of the new federal state was elected.

A major factor in determining the form the new federal government would take was the aftermath of the recently concluded American Civil War, which had seen the southern states forcibly re-incorporated into the United States of America and slavery abolished. While few Germans were particularly sympathetic toward the precise institution (i.e., slavery) which had precipitated civil war in America, the prevailing viewpoint outside the U.S. at this time was that the slaves had only been emancipated as a reprisal for Southern secession from the American Union. With this in mind, many Catholics especially in Southern Germany feared that Prussia might one day might attempt to engineer a similar sort of secession crisis within a united Germany and use it as a pretext to launch a violent repression against Catholicism throughout Germany. Thus, it was Bismarck's intention to make the new federal state look like a confederation in the tradition of the German Confederation and explains the name of the country and several provisions in the draft constitution — Bismarck needed to make the federal state more attractive (or at least less repulsive) to southern German states which might later join.[16]

Constructing the nation-state

During the roughly three and a half years of the North German Confederation its major action existed in legislation unifying Northern Germany. The Reichstag decided on laws concerning, for example:

- free movement of citizens within the territory of the Confederation (1867)

- a common postal system (1867–1868)

- common passports (1867)

- equal rights for the different religious denominations (1869)

- unified measures and weights (with the obligatory introduction of the metric system)

- penal code (1870)

The North German Confederation also became a member of the Zollverein, the German customs union of 1834.

Political system

The North German Constitution of 16 April 1867 created a national parliament with universal suffrage (for men above the age of 25), the Reichstag. Another important organ was the Bundesrat, the 'federal council' of the representatives of the state governments. To adopt a law, a majority in the Reichstag and in the Bundesrat was necessary. This gave the allied governments, meaning the states (and, depending on the state, their princes), an important veto.

Executive power was vested in a chancellor, being the only responsible federal minister of the country. There was no formal cabinet, and in the time of the North German Confederation there were only two government departments anyway: the Bundeskanzleramt as the general office of the chancellor, and, since early 1870, the foreign office.

The chancellor was installed and dismissed by the Bundespräsidium. This office belonged automatically to the Prussian king (art. 11). The holder was de facto the head of state of the North German Confederation. (Bismarck wanted to avoid the title Präsident with its republican air.)

For all intents and purposes, the Confederation was dominated by Prussia. It had four-fifths of the confederation's territory and population – more than the other 21 members combined. The Prussian king was a kind of head of state. Chancellor Bismarck was also prime minister and foreign minister of Prussia. In that role he instructed the Prussian votes in the Bundesrat. Prussia had 17 of 43 votes in the Bundesrat despite being by far the largest state but could easily get a majority by making alliances with the smaller states.

Customs union

In June 1867 a conference took place between Prussia and the south German states, who were not members of the North German Confederation. After pressure from Prussia, new Customs Union (Zollverein) treaties were signed the following month. Henceforth, the governing bodies of the Customs Union were the Bundesrat and Reichstag of the North German Confederation, augmented by representatives of the south German governments in the former and members from these states elected in the same way as the others in the latter. When augmented thus for customs matters, the institutions were known as the Federal Customs Council and the Customs Parliament (Zollparlament).[17] On 1 January 1868, the new institutions came into force. Bismarck hoped that the Zollverein might become the vehicle of German unification. But in the 1868 Zollparlament election the South Germans voted mainly for anti-Prussian parties.

On the other hand, the two Mecklenburg duchies and three Hanseatic cities were initially not members of the Customs Union. The Mecklenburgs and Lübeck joined soon after the North German Confederation was formed. Eventually, after heavy Prussian pressure, Hamburg acceded to the Customs Union in 1888. Bremen joined at the same time. Despite this, all these states fully participated in the federal institutions, even while outside the Customs Union and not directly affected by their decisions in that regard.

Postage stamps

One of the functions of the confederation was to handle mail and issue postage stamps.

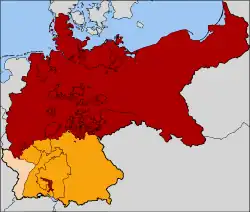

Transition to the German Empire

In mid-1870, a diplomatic crisis concerning the Spanish throne led eventually to the Franco-Prussian War.[18] During the war, in November 1870, the south German states of Bavaria, Württemberg, and Baden (together with the parts of Hesse-Darmstadt that were left out of the Confederation) joined the North German Confederation. On this occasion, the country adopted a new constitution, and the name of the federal state was changed to Deutsches Reich (German Empire).

According to a minority among German experts, the North German Confederation and the southern states created a new federal state (the German Empire). Indeed, Bismarck allowed the south German states to save face and therefore used terminology suggesting a new creation. But Kotulla emphasizes that legally only accession of the southern states to the North German Confederation was possible; the legal basis for such an accession was art. 79 of the North German federal constitution.[19]

On 10 December 1870 the Reichstag of the North German Confederation had adopted a new constitution, still titled as one of the Deutscher Bund (German Confederation) in spite of establishing for the state a new name Deutsches Reich (German Realm or German Empire) and granting the title of German Emperor to the King of Prussia holding the Bundespräsidium of the Confederation; it entered into force on 1 January 1871, but lasted only four months.[20]

Following the victory in the war with France, the German princes and senior military commanders proclaimed Wilhelm "German Emperor" in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles.[21] This latter date was later customarily celebrated as the symbolic day of 'foundation of the German Empire' (Deutsche Reichsgründung), although it had no constitutional meaning.[22]

After a new Reichstag was elected on 3 March 1871, the transition from the Confederation to the Empire was completed when the permanent Constitution of the German Empire prevailing until the demise of the monarchy entered into force on 4 May 1871, while France recognised the empire on 10 May 1871 in the Treaty of Frankfurt.[23][24]

The three constitutions (1867, January 1871, and April 1871) were nearly identical. It took roughly a decade to develop the country into a fully grown federal state, with several governmental departments (a kind of ministries), responsible state secretaries (a kind of ministers, 1878), and an imperial court (Reichsgericht, 1879).

List of member states

.jpg.webp)

All of the member states had already belonged to the German Confederation of 1815–66. Austria and the south German states Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden and the Grand Duchy of Hesse (Hesse-Darmstadt) remained outside of the North German Confederation. Though, the northern province Oberhessen of the Grand Duchy of Hesse did join.

In northern, central and eastern Germany, Prussia:

- had gathered a number of allies that joined the North German Confederation via the August treaties (Augustverträge) of August 1866;

- annexed four former enemy states (Hanover, Kurhessen, Nassau, Frankfurt) which became parts of Prussia (October 1866);

- included its own territories formerly outside of the Holy Roman Empire and the German Confederation, namely the East Prussian craddle of its statehood as well as the Prussian-conquered Polish territories (Province of Posen, West Prussia) in the new state, thus formally annexing them into Germany

- forced the remaining states into the North German Confederation via the peace treaties.

Lauenburg is sometimes mentioned as one of the member states, sometimes not. It was one of the three duchies that had earlier belong to Denmark. Lauenburg was a state with the Prussian king as duke until 1876, when it became a part of the Prussian province of Schleswig-Holstein.

| State | Capital | |

|---|---|---|

| Kingdoms (Königreiche) | ||

| Prussia (Preußen) as a whole (including Lauenburg) |

Berlin | |

| Saxony (Sachsen) | Dresden | |

| Grand Duchies (Großherzogtümer) | ||

| Hesse (Hessen) (Only Upper Hesse, the province north of the river Main) |

Giessen | |

| Mecklenburg-Schwerin | Schwerin | |

| Mecklenburg-Strelitz | Neustrelitz | |

| Oldenburg | Oldenburg | |

| Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach) | Weimar | |

| Duchies (Herzogtümer) | ||

| Anhalt | Dessau | |

| Brunswick (Braunschweig) | Braunschweig | |

| Saxe-Altenburg (Sachsen-Altenburg) | Altenburg | |

| Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha) | Coburg | |

| Saxe-Meiningen (Sachsen-Meiningen) | Meiningen | |

| Principalities (Fürstentümer) | ||

| Lippe | Detmold | |

| Reuss-Gera (Junior Line) | Gera | |

| Reuss-Greiz (Elder Line) | Greiz | |

| Schaumburg-Lippe | Bückeburg | |

| Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt | Rudolstadt | |

| Schwarzburg-Sondershausen | Sondershausen | |

| Waldeck and Pyrmont (Waldeck und Pyrmont) | Arolsen | |

| Free and Hanseatic Cities (Freie und Hansestädte) | ||

| Bremen | ||

| Hamburg | ||

| Lübeck | ||

See also

Notes

- ↑ de facto, except Austrian Empire, Duchy of Limburg (1839–1867), Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Principality of Liechtenstein

References

- ↑ An alternative translation is "North German Federation." The German word Bund is used in the German constitutional history (a) for confederations (associations of states, in German Staatenbund) such as the German Confederation of 1815, but (b) also for federations (federal states, in German Bundesstaat or Föderaler Staat) such as the Federal Republic of Germany or the United States of America.

- ↑ See Michael Kotulla: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte. Vom Alten Reich bis Weimar (1495–1934). Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 526. R. Stettner, in: H. Dreier (ed.), Grundgesetz-Kommentar, vol. 2, second edition 2006, Art. 123, Rn. 14. Bernhard Diestelkamp: Rechtsgeschichte als Zeitgeschichte. Historische Betrachtungen zur Entstehung und Durchsetzung der Theorie vom Fortbestand des Deutschen Reiches als Staat nach 1945. In: Zeitschrift für Neuere Rechtsgeschichte 7 (1985), pp. 187 and following.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte. Vom Alten Reich bis Weimar (1495–1934). Springer, Berlin 2008, pp. 487–489.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte. Vom Alten Reich bis Weimar (1495–1934). Springer, Berlin 2008, pp. 525–527.

- ↑ Die Reichsgründung 1871 (The Foundation of the Empire, 1871), Lebendiges virtuelles Museum Online, accessed 2008-12-22. German text translated: [...] on the wishes of Wilhelm I, on the 170th anniversary of the elevation of the House of Brandenburg to royal status on January 18, 1701, the assembled German princes and high military officials proclaimed Wilhelm I as German Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at the Versailles Palace.

- ↑ Crankshaw, Edward. Bismarck. New York, The Viking Press, 1981, p. 299.

- ↑ Ernst Rudolf Huber: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1789. Vol. III: Bismarck und das Reich. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, p. 747.

- ↑ Ploeckl, Florian (2020). "A novel institution: the Zollverein and the origins of the customs union". Journal of Institutional Economics. 17 (2): 305–319. doi:10.1017/S1744137420000387. ISSN 1744-1374. S2CID 211238300.

- ↑ "Germany – The age of Metternich and the era of unification, 1815–71". Britannica.

- ↑ Ploeckl, Florian (2020). "A novel institution: the Zollverein and the origins of the customs union". Journal of Institutional Economics. 17 (2): 305–319. doi:10.1017/S1744137420000387. ISSN 1744-1374. S2CID 211238300.

- ↑ David E. Barclay: Preußen und die Unionspolitik 1849/1850. In: Gunther Mai (ed.): Die Erfurter Union und das Erfurter Unionsparlament 1850. 2000, pp. 53–80, here pp. 78–80.

- ↑ Ernst Rudolf Huber: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1789. Vol. III: Bismarck und das Reich. 3rd edition, Kohlhammer Verlag, Stuttgart et al. 1988, pp. 536/537.

- ↑ Ernst Rudolf Huber: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1789. Vol. III: Bismarck und das Reich. W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1963, p. 570.

- ↑ Michael Kotulla: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte. Vom Alten Reich bis Weimar (1495–1934). Springer, Berlin 2008, pp. 491–492.

- ↑ Ernst Rudolf Huber: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1789. Vol. III: "Bismarck und das Reich". 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart (et al.) 1988, pp. 580–583.

- ↑ Christoph Vondenhoff: Hegemonie und Gleichgewicht im Bundesstaat. Preußen 1867–1933: Geschichte eines hegemonialen Gliedstaates. Diss. Bonn 2000, Shaker Verlag, Aachen 2001, pp. 31–33.

- ↑ Henderson, William. The Zollverein. Publ Cambridge University Press, 1939; p.314

- ↑ Görtemaker, Manfred (1983). Deutschland im 19. Jahrhundert: Entwicklungslinien. Opladen. p. 244. ISBN 9783663096559.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Michael Kotulla: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte. Vom Alten Reich bis Weimar (1495–1934). Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 526.

- ↑ Case, Nelson (1902). European Constitutional History. Cincinnati: Jennings & Pye. pp. 139–140. OCLC 608806061.

- ↑ Die Reichsgründung 1871 (The Foundation of the Empire, 1871), Lebendiges virtuelles Museum Online, accessed 2008-12-22. German text translated: [...] on the wishes of Wilhelm I, on the 170th anniversary of the elevation of the House of Brandenburg to royal status on January 18, 1701, the assembled German princes and high military officials proclaimed Wilhelm I as German Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at the Versailles Palace, and he accepted the title.

- ↑ Ernst Rudolf Huber: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1789. Vol. III: Bismarck und das Reich. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, pp. 750/751.

- ↑ Crankshaw, Edward. Bismarck. New York, The Viking Press, 1981, p. 299.

- ↑ Ernst Rudolf Huber: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1789. Vol. III: Bismarck und das Reich. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [et al.] 1988, p. 747.

Further reading

- Craig, Gordon A. Germany, 1866–1945 (1978) pp. 11–22 online edition

- Holborn, Hajo (1959). A History of Modern Germany: 1840–1945. Knopf. pp. 173–232. ISBN 9780394302782.

- Hudson, Richard. "The Formation of the North German Confederation." Political Science Quarterly (1891) 6#3 pp: 424–438. in JSTOR

- Nipperdey, Thomas. Germany from Napoleon to Bismarck: 1800–1866 (1996), very dense coverage of every aspect of German society, economy and government

- Pflanze, Otto. Bismarck and the Development of Germany, Vol. 1: The Period of Unification, 1815–1871 (1971)

- Taylor, A.J.P. Bismarck: The Man and the Statesman (1967) online edition

.svg.png.webp)