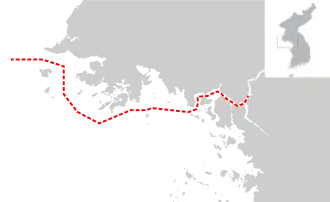

The Northern Limit Line or North Limit Line (NLL) – 북방한계선 (in ROK) – is a disputed maritime demarcation line in the Yellow (West) Sea between the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the north, and the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the south. This line of military control acts as the de facto maritime boundary between North and South Korea.[1][2]

Description

The line runs between the mainland portion of Gyeonggi-do province that had been part of Hwanghae before 1945, and the adjacent offshore islands, including Yeonpyeong and Baengnyeongdo. Because of the conditions of the armistice, the mainland portion reverted to North Korean control, while the islands remained a part of South Korea despite their close proximity.

The line extends into the sea from the Military Demarcation Line (MDL), and consists of straight line segments between 12 approximate channel midpoints, extended in an arc to prevent egress between both sides.[3][4] On its western end the line extends out along the 38th parallel to the median line between Korea and China.[5]

Origins

The 1953 Armistice Agreement, which was signed by both North Korea and the United Nations Command (UNC),[6] ended the Korean War and specified that the five islands including Yeonpyeong Island and Baengnyeong Island would remain under the control of the UNC and South Korea. However, they did not agree on a maritime demarcation line, primarily because the UNC wanted to base it on 2 nautical miles (3.7 km) or 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) of territorial waters, while North Korea wanted to use 12 nautical miles (22 km).[7][3]

In August 1953, shortly after the entry into force of the armistice agreement, the South Korean Syngman Rhee Provisional government, which opposed the armistice agreement, attempted to attack the DPRK on the west coast, ignoring the agreement. Accordingly, the United Nations Command set up the "Northern Limit Line" of the West Sea so that the ROK Armed Forces would not attack Hwanghae Island, and this is the starting point of the Northern Limit Line.[8][9]

After the United Nations Command and North Korea failed to reach an agreement, it is widely believed that the line was set by the UNC as a practical operational control measure a month after the armistice was signed, on August 30, 1953.[3][10] However original documentation recording this has not been found.[11] The line was originally drawn to prevent South Korean incursions into the north that threatened the armistice. However, its role has since been transformed to prevent North Korean ships heading south.[4]

A 1974 Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) research report investigating the origins of the NLL and its significance, declassified in 2000, found that the NLL was established in an order made on 14 January 1965 by the U.S. Commander Naval Forces, Korea. An antecedent line, under a different name, had been established in 1961 by the same commander. No documentation about the line earlier than 1960 could be located by the CIA, casting doubt on the belief that the NLL was created immediately after the armistice. The sole purpose of the NLL in this original order was to forbid UNC vessels from sailing north of it without special permission. The report noted, however, that in at least two places the NLL crosses into waters presumed to be under uncontested North Korean sovereignty. No evidence was found that North Korea had recognised the NLL.[11][12]

While the NLL was drawn up at a time when a territorial waters limit of 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) was the norm, by the 1970s a limit of 12 nautical miles (22 km) had become internationally accepted, and the enforcement of the NLL prevented North Korea, in areas, from accessing significant territorial waters (arguably actual or prospective).[4] In 1973, North Korea began disputing the NLL.[1] Later, after the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the NLL also prevented North Korea from establishing an effective Exclusive Economic Zone to control fishing in the area.[4][13]

It is unclear when North Korea was informed of the existence of the NLL. Many sources suggest this was done promptly, but in 1973 Deputy Secretary of State Kenneth Rush stated, in a now declassified, "Joint State-Defense Message" to the U.S. Embassy in Seoul that "We are aware of no evidence that NLL has ever been officially presented to North Korea."[14][15] However, South Korea argues that until the 1970s North Korea tacitly recognized the line as a sea demarcation line.[16] North Korea recorded in their 1959 Central Almanac a partial demarcation line close to the UNC controlled islands, at about three nautical miles distance, which South Korea argues shows North Korean acceptance of the NLL as a whole.[17]

Status

The border is not officially recognized by North Korea.[18] The North Korean and South Korean navies regularly patrol the area around the NLL. As North Korea does not recognise the line, its fishing boats work close to or over the limit line, escorted by North Korean naval boats.[19]

On 27 April 2018, North Korea and South Korea adopted the Panmunjom Declaration for Peace, Prosperity and Unification of the Korean Peninsula, which agreed that areas around the Northern Limit Line would be converted into a maritime peace zone in order to prevent accidental military clashes and guarantee safe fishing activities.[20]

United Nations Command's position

The UNC emphasized its position on the border issue on 23 August 1999, stating that the NLL issue was non-negotiable because the demarcation line had been recognized as the de facto maritime border for a considerable length of time by both Koreas:

The NLL has served as an effective means of preventing military tension between North and South Korean military forces for 46 years. It serves as a practical demarcation line, which has contributed to the separation of forces.[3]

The UNC insisted that the NLL must be maintained until a new maritime MDL could be established through the Joint Military Commission on the armistice agreement.[21]

However, a 1973 U.S. diplomatic cable, now declassified, noted that UNC protested North Korean intrusions within 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) of UNC controlled islands as armistice agreement violations, but did not protest NLL intrusions as the NLL was not mentioned in the armistice agreement. South Korea wished to describe all NLL penetrations as "military provocations", but the U.S. saw that as a major problem for the U.S. position on the armistice agreement.[22][23] In 1975 the UNC position was that North Korean fishing or patrolling south of the NLL, outside 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) of the UNC controlled islands, was not justification for any coercive actions by UNC controlled vessels; the UNC would not participate in establishing an exclusive South Korean fishing zone.[24]

North Korea's position

A: United Nations Command-created Northern Limit Line, 1953[26]

B: North Korea-declared "Inter-Korean MDL", 1999[27]

The locations of specific islands are reflected in the configuration of each maritime boundary, including

1. Yeonpyeong Island

2. Baengnyeong Island

3. Daecheong Island

When the 1953 Armistice was concluded between the U.N. and North Korea, agreement over a maritime extension of the demilitarized zone was not achieved. In 1955, DPRK proclaimed territorial waters extending 12 nautical miles (22 km). from the coastline.[28] Other than this, North Korea did not explicitly dispute or actively violate the NLL until 1973. First, the North Korean negotiators at the 346th meeting of the Military Armistice Commission challenged the status of the line.[1] North Korea followed this up by sending large groups of patrol ships over the NLL on about 43 occasions in October and November.[29][30] North Korea states that it had not been informed of the existence of the line,[16][31] which is now confirmed by declassified U.S. diplomatic cables,[14][15] so it could not dispute it earlier.

North Korea's official state news agency KCNA described the line as the "final line for stopping the defectors to the north" drawn to meet "Washington's self-justified interests."[31]

On 1 August 1977, North Korea established an Exclusive Economic Zone of up to 200 nautical miles (370 km).[32] It also attempted to establish a 50 nautical miles (93 km) military boundary zone around the islands claimed by South Korea along the NLL; however, this claim was rebuffed.[33][34]

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, North Korea wanted to establish a special economic zone and international port at Haeju, their southern deepwater port, to develop alternative trade opportunities. However, with the NLL enforced, access to Haeju required shipping to travel along North Korean coast for 65 nautical miles (120 km), often within 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) of the shore. This prevents the development of Haeju as a large international port.[35]

Since September 1999, North Korea has claimed a more southerly "West Sea Military Demarcation Line" (also called "Inter-Korean MDL"). This maritime demarcation line is an extension line from the land boundary equidistant from the north and south mainlands, with channels to the north-west islands under UNC control, claimed to be based on international law delimitation decisions.[2][3][36]

According to a 2002 Korean Central News Agency article the NLL violates the Korean armistice agreement and the 12 mile territorial waters stipulated by the UN Maritime Convention. The article claims the Northern Limit Line is a root cause of armed clashes, and by insisting on the line the U.S. and South Korean seek to use it to spark military conflict.[37] An earlier article reported that at meetings of the military armistice commission in December 1973 and July 1989 North Korea noted that future clashes were unavoidable unless a clear Military Demarcation Line was drawn in the West Sea, and urging the U.S. to negotiate such measures.[38]

On December 21, 2009, North Korea established a "peacetime firing zone" south of the NLL in waters disputed with South Korea.[39][40]

For many years North Korea has sold fishing rights in the area of the NLL to Chinese fishing companies, which South Korea regards as illegal fishing.[41]

South Korea's position

The South Korean position from the 1970s has been:[29]

- The NLL is an indispensable measure to administer the Armistice Agreement;

- The NLL is in the approximate mid-position between the islands and the North Korean mainland;

- North Korea acquiesced to the NLL until 1973, so implicitly recognized the NLL.

In 2002 the Ministry of National Defense published a paper reasserting the legitimacy of the NLL, and arguing that North Korea's claims regarding NLL were groundless.[16] The paper concluded that:

- The NLL has been the practical sea demarcation line for the past 49 years and was confirmed and validated by the 1992 South-North Basic Agreement;

- Until a new sea nonaggression demarcation line is established, the NLL will be resolutely maintained like the ground Military Demarcation Line, and decisive responses will be made to all North Korean intrusions;

- Any new sea nonaggression demarcation must be established through South-North discussions, and the NLL is not the subject of negotiation between the US or UNC and the North;

- North Korea's claims violate the Armistice Agreement and are not compatible with the spirit and provisions of international law.

On October 4, 2007, South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun and North Korean leader Kim Jong-il addressed the issue of NLL disputes in a joint statement:[2]

"The South and the North have agreed to create a 'special peace and cooperation zone in the West Sea' encompassing Haeju and vicinity in a bid to proactively push ahead with the creation of a joint fishing zone and maritime peace zone, establishment of a special economic zone, utilization of Haeju harbor, passage of civilian vessels via direct routes in Haeju and the joint use of the Han River estuary."

However the following South Korean President Lee Myung-bak rejected this approach, describing the NLL as a "critical border that contributes to keeping peace on our land."[2]

South Korean academics at the Korea Maritime Institute argued in 2001 that the legal situation between the two Koreas is a special regime governed by the armistice agreement, and not usual international law such as the Law of the Sea. Consequently, the NLL is subject to political agreement between the two Koreas, rather than international law remedies.[29]: 212–214

On November 1, 2018, a buffer zone was established near Yeonpyeong Island.[42]

The U.S. position

The United States government position, separate from the United Nations Command, is not clearly expressed. When asked about the NLL, United States government representatives usually refer questioners to the UNC in South Korea.[14]

In February 1975, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wrote in a confidential cable, now declassified, that the "Northern Patrol Limit Line does not have international legal status ... Insofar as it purports unilaterally to divide international waters, it is clearly contrary to international law and USG Law of the Sea position."[14][43] Earlier in 1973 a "Joint State-Defense Message" to the U.S. Embassy in Seoul stated that South Korea "is wrong in assuming we will join in attempts to impose NLL",[14] and the U.S. Ambassador told the South Korean government that the 12-mile (19 km) North Korean territorial sea claim created a zone of uncertain status with respect to the NLL.[44]

In November 2010, following the North Korean Shelling of Yeonpyeong, President Barack Obama said the U.S. stood "shoulder to shoulder" with South Korea and condemned the attack, but did not specifically address the NLL.[14]

Border clashes

Clashes between North and South Korean fishing boats and naval vessels have frequently occurred along the NLL. As the waters along the NLL are rich in blue crab, the seaborne clashes have sometimes been dubbed the "Crab Wars".[45] Incidents include:

- First Battle of Yeonpyeong (1999) – four North Korean patrol boats and a group of fishing boats crossed the border and initiated a gun battle that left one North Korean vessel sunk, five patrol boats damaged, 30 sailors killed, and 70 wounded.

- Second Battle of Yeonpyeong (2002) – two North Korean patrol boats crossed the NLL near Yeonpyeong island and started firing; after becoming outnumbered and suffering damage, the vessels retreated.

- On 1 November 2004 three North Korean vessels crossed the NLL. They were challenged by South Korean patrol boats, but did not respond. The ROK vessels opened fire and the DPRK boats withdrew without returning fire. No casualties were reported.

- Battle of Daecheong (2009) – A North Korean gun boat crossed the NLL and entered waters near Daecheong Island, South Korean vessels opened fire reportedly causing serious damage to a North Korean patrol ship and one death.[46]

- On January 27, 2010, North Korea fired artillery shots into the water near the NLL and South Korean vessels returned fire.[47] The incident took place near the South Korean-controlled Baengnyeong Island.[48] Three days later, North Korea continued to fire artillery shots towards the area.[49]

- ROKS Cheonan sinking (2010) – The ROKS Cheonan (PCC-772), a South Korean corvette, was sunk by an explosion, killing 46 sailors; the resulting South-Korea-led international investigation blamed North Korea, which denied involvement.

- Bombardment of Yeonpyeong (2010) – North Korean forces fired around 170 artillery shells at Yeonpyeong, killing four South Koreans, injuring 19, and causing widespread damage to the island's civilian fishing village.

See also

- Armistice Agreement of 1953 – full text of the armistice

- Korean Demilitarized Zone – land border

- Syngman Rhee Line – 1950s South Korean maritime boundary claim beyond accepted territorial waters

- Cod Wars – conflict between the United Kingdom and Iceland about fishing rights that escalated to military involvement

References

- 1 2 3 Elferink, Alex G. Oude. (1994). The Law of Maritime Boundary Delimitation: a Case Study of the Russian Federation, p. 314, at Google Books

- 1 2 3 4 Jon Van Dyke (July 29, 2010). "The Maritime boundary between North & South Korea in the Yellow (West) Sea". 38 North. U.S.-Korea Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moo Bong Ryoo (11 March 2009). The Korean Armistice and the Islands (PDF). Strategy research project (Report). U.S. Army War College. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 12, 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Kotch, John Barry; Abbey, Michael (2003). "Ending naval clashes on the Northern Limit Line and the quest for a West Sea peace regime" (PDF). Asian Perspectives. 27 (2): 175–204. doi:10.1353/apr.2003.0024. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2010-11-27.

- ↑ The Republic of Korea Position Regarding the Northern Limit Line (Report). The Ministry of National Defense, Republic of Korea. August 2002. p. map II.4.A. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ Armistice Agreement, paragraph 13(b)."Transcript of Armistice Agreement for the Restoration of the South Korean State (1953)". Our Documents. 1953-07-27. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ↑ Kim, Jung-Gun (Spring–Summer 1985). "Reflections on the attitude of North Korea toward the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III Treaty)". Asian Perspective. 9 (1): 57–94. JSTOR 43738042.

- ↑ "북방한계선이 영토선이라고?". 2009-02-04. 출판사: 오마이뉴스.

- ↑ Press release note, 1960 Lee Young-hee

- ↑ Yŏnʼguwŏn, Hanʼguk Kukpang (1999). "Defense white paper". Ministry of National Defense, Republic of Korea.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Roehrig, Terence (September 30, 2011). The Northern Limit Line: The Disputed Maritime Boundary Between North and South Korea (PDF) (Report). The National Committee on North Korea. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ↑ The West Coast Korean Islands (PDF) (Report). Central Intelligence Agency. January 1974. BGI RP 74-9 / CIA-RDP84-00825R00300120001-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ↑ Glionna, John M. (January 6, 2011). "Sea border a trigger for Korean peninsula tension". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Daniel Ten Kate & Peter S. Green (December 17, 2010). "Holding Korea Line Seen Against Law Still U.S. Policy". Bloomberg. San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2010-12-18. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- 1 2 Rush, Kenneth (22 December 1973), ROKG legal memorandum on northwest coastal incidents, U.S. Department of State, 1973STATE249865, retrieved 18 December 2010,

We are aware of no evidence that NLL has ever been officially presented to North Korea. We would be in an extremely vulnerable position of charging them with penetrations beyond a line they have never accepted or acknowledged. ROKG is wrong in assuming we will join in attempts to impose NLL on NK.

- 1 2 3 The Republic of Korea Position Regarding the Northern Limit Line (Report). The Ministry of National Defense, Republic of Korea. August 2002. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ The Republic of Korea Position Regarding the Northern Limit Line (Report). The Ministry of National Defense, Republic of Korea. August 2002. p. map II.2.C (map copy on commons). Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ↑ Roehrig, Terence (2009). "North Korea and the Northern Limit Line". North Korean Review. 5 (1): 8–22. doi:10.3172/NKR.5.1.8.

- ↑ Hyŏn, In-tʻaek; Schreurs, Miranda Alice (2007). The environmental dimension of Asian security: conflict and cooperation over energy, resources, and pollution. US Institute of Peace Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-1929223732.

- ↑ Yoo Kang-moon, Kim Ji-eun (7 May 2018). "Unification minister hints at possible shift in North Korea's attitude toward Northern Limit Line". The Hankyoreh. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ↑ NLL – Controversial Sea Border Between S.Korea, DPRK November 21, 2002. PRC newspaper People's Daily

- ↑ U.S. Ambassador Francis Underhill (20 December 1973), ROK legal position on northwest coastal incidents, U.S. Department of State, 1973SEOUL08574, retrieved 20 December 2010,

We have protested, as armistice agreement violations, intrusions within three mile contous waters of UNC controlled islands. However UNC has not protested NLL intrusions since line is not specifically mentioned in armistice agreement.

- ↑ Henry Kissinger (7 January 1974), Northern Limit Line: Defining Contiguous Waters, U.S. Department of State, 1974STATE002540, retrieved 20 December 2010,

UNC Rules of Engagement has been that territorial sea rights will be enforced within three miles of ROK land areas.

- ↑ Carlyle E. Maw (23 August 1975), Future actions in international waters off ROK coast, U.S. Department of State, 1975STATE201476, retrieved 23 December 2010,

We are concerned that ROK may tend to define very broadly what is an NK hostile act or threat to security, and hence may wish to take counter-actions which would be difficult for us to justify. ... Mere NK fishing or patrolling in high seas south of NLL, even if near ROK fishing boats, cannot be used as justification for coercive actions by UNC. ... ROKG should clearly understand that we will not participate in any action to establish area as exclusive ROK fishing zone.

- ↑ Ryoo, Moo Bong. (2009). "The Korean Armistice and the Islands," p. 13 or p. 21.. Strategy research project at the U.S. Army War College; retrieved 26 Nov 2010.

- ↑ "Factbox: What is the Korean Northern Limit Line?" Reuters (UK). November 23, 2010; retrieved 26 Nov 2010.

- ↑ Van Dyke, Jon et al. "The North/South Korea Boundary Dispute in the Yellow (West) Sea," Marine Policy 27 (2003), 143–58; note that "Inter-Korean MDL" is cited because it comes from an academic source Archived 2012-03-09 at the Wayback Machine and the writers were particular enough to include in quotes as we present it. The broader point is that the maritime demarcation line here is NOT a formal extension of the Military Demarcation Line; compare "NLL—Controversial Sea Border Between S.Korea, DPRK, " People's Daily (PRC), November 21, 2002; retrieved 22 Dec 2010

- ↑ Roehrig, Terence, "Korean Dispute over the Northern Limit Line: Security, Economics, or International Law?," Maryland Series in Contemporary Asian Studies, Vol. 2008: No. 3, pp. 8–9.

- 1 2 3 Seong-Geol Hong; Sun-Pyo Kim; Hyung-Ki Lee (2001-06-30). "Fisheries Cooperation and Maritime Delimitation Issues between North Korea and Its Neighboring Countries" (PDF). Ocean Policy Research. Korea Maritime Institute. 16 (1): 191–216. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Editorial, Reuters (23 November 2010). "Factbox: What is the Korean Northern Limit Line?". Reuters.

{{cite news}}:|first=has generic name (help) - 1 2 "Truth behind "Northern Limit Line" Disclosed". Korean Central News Agency. June 25, 2007.

- ↑ Central People's Committee (21 June 1977). "Decree by the Central People's Committee establishing the Economic Zone of the People's Democratic Republic of Korea" (PDF). United Nations – Office of Legal Affairs. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ Johnston, Douglas M.; Valencia, Mark J. (1991). Pacific Ocean boundary problems: status and solutions. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 81. ISBN 978-0792308621.

- ↑ Maritime Claims Reference Manual – Korea, Democratic People's Republic of (North Korea) (PDF) (Report). U.S. Department of Defense. June 23, 2005. DoD 2005.1-M. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-15. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- ↑ Rodger Baker (24 November 2010). "Importance of the Koreas' Northern Limit Line". STRATFOR. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ↑ KPA urges U.S. and S. Korea to accept maritime demarcation line at West Sea. Korean Central News Agency. July 21, 1999.

- ↑ "Northern Limit Line rejected". Korean Central News Agency. 2 August 2002. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ "Withdrawal of "northern limit line" called for". Korean Central News Agency. 9 July 2002. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ N. Korea sets 'firing zone' along western sea border. Yonhap. December 21, 2009.

- ↑ "KPA Navy Sets up Firing Zone on MDL". Korean Central News Agency. December 21, 2009. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ↑ "South Korea's 'Razor Reef' Deters Illegal Fishing". Stratfor. 22 August 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ↑ "[File] NLL buffer zone, there is a Marine Corps". www.tellerreport.com. 2 November 2018.

- ↑ Henry Kissinger (28 February 1975), Public affairs aspects of North Korea boat/aircraft incidents, U.S. Department of State, 1975STATE046188, retrieved 18 December 2010

- ↑ U.S. Ambassador Francis Underhill (18 December 1973), Defusing western coastal island situation, U.S. Department of State, 1973SEOUL08512, retrieved 18 December 2010,

there is an area between the two island groups off the Ongjin Peninsula where a 12-mile North Korean territorial sea claim and the Northern Limit Line create a zone of uncertain status.

- ↑ Glosserman, Brad (June 14, 2003). "Crab wars: Calming the waters in the Yellow Sea". Asia Times. Archived from the original on June 17, 2003. Retrieved 2010-11-25.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Kim, San (November 10, 2009). Koreas clash in Yellow Sea, blame each other. Yonhap.

- ↑ North and South Korea exchange fire near sea border. BBC News. January 27, 2010.

- ↑ N. Korea fires into western sea border. Yonhap. January 27, 2010.

- ↑ Tang, Anne (January 29, 2010). "DPRK fires artillery again near disputed sea border: gov't". Xinhua. Archived from the original on February 2, 2010.

Further reading

- Van Dyke, Jon M., Mark J. Valencia and Jenny Miller Garmendia. "The North/South Korea Boundary Dispute in the Yellow (West) Sea". Marine Policy 27 (2003), 143–158.

- Roehrig, Terence. "The Origins of the Northern Limit Line Dispute". NKIDP e-Dossier no. 6 (May 2012).