Northern Michigan

Northern Lower Michigan | |

|---|---|

Northern Michigan is highlighted in light green. | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Michigan |

| Population | |

| • Total | 506,658 |

| Time zone | Eastern: UTC −5/−4 |

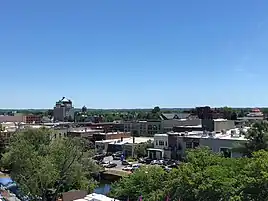

Northern Michigan, also known as Northern Lower Michigan (known colloquially to residents of more southerly parts of the state and summer residents from cities such as Detroit as "Up North"), is a region of the U.S. state of Michigan. A popular tourist destination, it is home to several small- to medium-sized cities, extensive state and national forests, lakes and rivers, and a large portion of Great Lakes shoreline. The region has a significant seasonal population much like other regions that depend on tourism as their main industry. Northern Lower Michigan is distinct from the more northerly Upper Peninsula and Isle Royale, which are also located in "northern" Michigan. In the northernmost 21 counties in the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, the total population of the region is 506,658 people.[upper-alpha 1]

History

Pre-colonial era: itinerant Native American tribes

For thousands of years before the French and English set up colonies in the region, Northern Michigan was inhabited by Native American cultures and succeeding tribes. Northern Michigan was the southern extent of the area scholars believed occupied by prehistoric inhabitants known as the Laurel complex. They were part of the Hopewell Indian exchange system, which is named after a prehistoric tribe that existed in the Great Lakes region.[3]

According to Menominee tradition, this tribe's original homeland was farther north, near present-day Sault Ste. Marie and Michilimackinac. At some period before European contact (probably around 1600), they were forced southwest to the Menominee River by arrival of the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi from the east.[4] Odawa history written by Andrew Blackbird records that Emmet County was thickly populated by a race of Indians that they called the Mush-co-desh, which means "the prairie tribe". The Mush-co-desh had an agrarian society and were said to have "shaped the land by making the woodland into prairie as they abandoned their old worn out gardens which formed grassy plains". Ottawa tradition claims that they slaughtered from forty to fifty thousand Mush-co-desh and drove the rest from the land after the Mush-co-desh insulted an Ottawa war party. At this same time, the areas surrounding the Straits of Mackinac, was home to the Michinemackinawgo. [5] They were a race of natives of small stature that were nearly wiped out by the Iroquois in the 1640s during the Beaver Wars. The remnants of this race were taken in by the Ojibwe and still exist today amongst the Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians. [6]

In the historic period, the Anishinaabe/Algonquian-speaking peoples known as the Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi, formed a loose confederation which they called the Council of Three Fires. They inhabited areas surrounding the Straits of Mackinac, the upper and lower peninsulas of Michigan, and the northern islands and shoreline of Canada along Lake Huron.

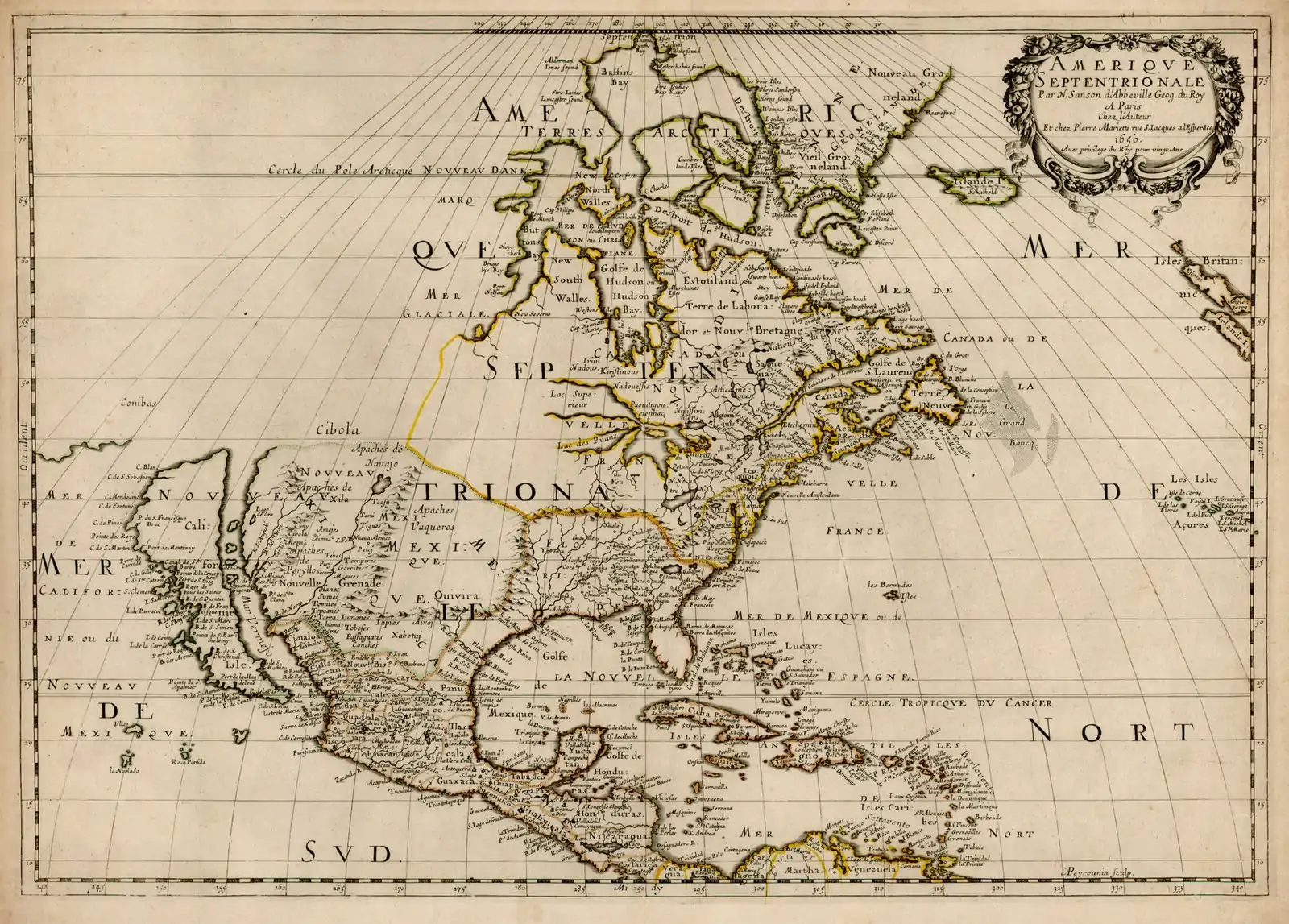

French and English colonial eras: fur trade and exploration based at the Straits

Initial colonial influence on Natives: French exploration and Beaver Wars

In 1608, Samuel de Champlain established Quebec as part of New France. He sent coureur des bois such as Étienne Brûlé into the woods to establish relations with the Indians. Around 1615 or 1616, Champlain traveled to Georgian Bay via the French River and met Ottawa and Huron Indians on the south end near Penetanguishene.[8][9][10][11] The French established the North American fur trade with Indian tribes. In the decades that followed, French explorers and missionaries continued to explore the "Upper Country" of New France that included the Upper Great Lakes. In 1634, Jean Nicolet passed through the straits of Mackinac on the way to Wisconsin.[12] While France colonized the interior lands along the St. Lawrence River, the Dutch and English began colonizing the East Coast of North America, setting up fur trade and arming the Iroquois along the east and southeast of the Great Lakes. Competition for trade and pelts resulted in the brutal Beaver Wars. The Iroquois pushed west into the Great Lakes territory, displacing the tribes who had settled there before. As a result of an Iroquois attack and dispersal of the Huron from Southern Ontario in 1649, the Huron sought refuge with the Ojibwe at Michilimackinac where eventually a Jesuit mission was established for their care.[13]

Jesuit Mission at St. Ignace (1671–1696)

Jesuit Father Marquette set up a mission in St. Ignace in 1671. While the Beaver Wars raged on, Marquette evangelized the Indians. From May 17, 1673, until Marquette's death near Ludington on May 18, 1675, Father Marquette and Louis Jolliet explored and mapped Lake Michigan and the northern portion of the Mississippi River. In 1679, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle and Father Louis Hennepin set out on Le Griffon to find the Northwest Passage; it was the first known sailing ship to sail in Northern Michigan. They sailed across Lake Erie, Lake Huron, and Lake Michigan through uncharted waters, which previously only men in canoes had explored. After Marquette's death, the mission was taken over by Father Phillip Pierson, and then Father Nouvel.[15]

Father Henri Nouvel was "superior of the Ottowa mission",[16] Nouvel served in this position from 1672 to 1680 (with a two-year break in 1678–1679), and again from 1688 to 1695.[17] Under Nouvel, a new chapel was built in approximately 1674. By 1683 the mission was so successful and prosperous that three priests, Fathers Nicholas Potier, Enjalran, and Pierre Bailloquet, were assigned there.[15] The establishment of a French garrison at St. Ignace in 1679 disrupted relations between the French and the local population, as the soldiers were less educated and amiable than the missionaries.

1680s: Fortification (Fort de Buade) at St. Ignace

In 1683, Governor Joseph-Antoine de La Barre ordered Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut and Olivier Morel de La Durantaye to establish a strategic presence on the north shore of the Straits of Mackinac, which connected Lake Michigan and Lake Huron of the Great Lakes. They fortified the Jesuit mission at St. Ignace and La Durantaye settled in as overall commander of the French forts in the northwest: Fort Saint Louis des Illinois (Utica, Illinois); Fort Kaministigoya (Thunder Bay, Ontario); and Fort la Tourette (Lake Nipigon, Ontario). He was also responsible for the region around Green Bay in present-day Wisconsin. In the spring of 1684, La Durantaye led a relief expedition from Saint Ignace to Fort Saint Louis des Illinois, which had been besieged by the Seneca (part of the Iroquois Confederacy) as part of the Beaver Wars; they sought to gain more hunting grounds in order to control the lucrative fur trade. That summer and again in 1687, La Durantaye led coureurs de bois and Indians from the Straits against the Seneca homeland in the territory of western upper New York state. During these years, English traders from New York penetrated the Great Lakes and also traded at Michilimackinac. This, and the outbreak of war between England and France in 1689, led to the new commandant Louis de La Porte de Louvigny directing construction of Fort de Buade in 1690.

1690s: Cadillac at Fort de Buade; St. Ignace Fort and Mission later abandoned

In the 1690s, commander Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac used Fort de Buade as a base of operations to explore and map the Great Lakes. Cadillac left St. Ignace in 1697 and the Jesuits vacated their residence and church by 1705.[18]

The Beaver Wars ended when the Great Peace of Montreal was signed in 1701 in Montreal by the French and 39 Indian chiefs including Kondiaronk (the chief of the Mackinaw-area Huron). When Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac left the area in 1701 to found Detroit, taking many of the St. Ignace residents with him, the importance of the mission declined dramatically.[15]

Early 1700s: Fort Michilimackinac established as a New France outpost

The St. Ignace mission remained open until 1705, when it was abandoned and burned by Father Étienne de Carheil.[19] It was reopened in 1712, and operated on the north shore of the Straits until 1741, when it was relocated to the south shore.[20] With the relocation of the mission, the exact location of Marquette's chapel was lost.[19]

In 1712, at the beginning of a 25-year war between the French and the Fox tribe, Canadian Governor Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil sent Constant le Marchand de Lignery to reoccupy the former post of Michilimackinac, which had been abandoned in 1696 by royal orders.

Around 1715 (during the First Fox War), the French re-established a Northern Michigan military outpost at a new site on the northern tip of the lower peninsula and called it Fort Michilimackinac. This location became the new locus for fur and other trade, and mission work with the natives.

Lignery returned to the command of Michilimackinac in 1722 after an absence of about three years fighting the Fox in Illinois. He carried out the orders of acting Governor Charles Le Moyne de Longueuil and (starting in 1726) New France governor Charles de la Boische, Marquis de Beauharnois.

From 1720 to 1722, Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix stopped at Michilimackinac and other points in Northern Michigan while seeking a Pacific Ocean passage. In 1728, fur trader Augustin Langlade obtained a fur trading license at Michilimackinac. He and his half-Ottawa son Charles Michel de Langlade (born at the fort in 1729) would later strongly influence the Northern Michigan fur trade as well as French relations with Great Lakes tribes during the 1712 to 1733 Fox Wars and the 1754–1763 French and Indian War.

By 1745, the Odawa had created settlements down the coast of Lake Michigan into the Grand Traverse Bay area, with an approximate population between 1,550 and 3,000. This population varied with the seasons, as the tradition was to migrate inland to different camps (sometimes as far as to Illinois) depending upon the season.[21] Some Ojibwe bands also shared the Grand Traverse Bay region with the Odawa.[21]

In 1751, a Jesuit Mission to the Odawa was established in Manistee.[22]

1760s: Beginning of the British era

In the 1760s after defeating the French in the French and Indian War (and in the Seven Years' War in Europe), the British took control of the Straits of Mackinac and other French territory east of the Mississippi River. They encountered resistance from the Natives, who rose up in what was called Pontiac's War (1763–1766). On June 2, 1763 Ojibwe and Sauk warriors killed the majority of white residents at Fort Michilimackinac. Alexander Henry the elder, one of the survivors, was taken captive and transported to Beaver Island but was rescued by the Odawa Wawatam. The British built the more substantial Fort Mackinac at the site in 1780.[23][24]

The success of rebels in the American Revolutionary War led to another change in parties in the region. Great Britain formally ceded Fort Mackinac at Mackinac Island to the newly independent United States in the Treaty of Paris in 1783, but the British Army refused to evacuate the posts on the Great Lakes until 1796. At that time, they transferred the forts at Detroit, Mackinac, and Niagara to the Americans. British and American forces contested the area again throughout the War of 1812. The boundary was not settled until 1828, when Fort Drummond, a British post on nearby Drummond Island, was evacuated.

1780s to 1830s: United States territorial acquisition, continued fur trade, and territorial disputes

The entire Straits area was officially acquired by the United States from the British through the Treaty of Paris in 1783 and settlement permitted by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. However, much of the British forces did not leave the Great Lakes area until after 1794, when Jay's Treaty established U.S. sovereignty over the Northwest Territory with Northern Michigan part of "Knox County".[25] Between 1795 and 1815 a system of Métis (descendants of indigenous women who married French (and later Scottish) fur trappers and traders) settlements and trading posts was established throughout Michigan, Wisconsin, and to a lesser extent in Illinois and Indiana. As late as 1829 the Métis were dominant in the economy of Wisconsin and influential in Northern Michigan[26] in part because they were able to work as intermediaries between natives and white fur traders. US settlement of the Michigan Territory (established in 1805) was punctuated by misunderstandings with Native Americans over land ownership. Meanwhile, in 1804, Mackinac Island was the center of the American fur trade.[27] Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard was one of many of John Jacob Astor's trappers and voyageurs[28] who plied the waters of the Great Lakes in Mackinaw boats and collected pelts to be sold in Europe.[29] As US Congress passed trade and intercourse acts to regulate trade with the natives, the Office of Indian Trade established a US Trading Post "factory" at Mackinaw that was in place until the War of 1812.[30][31] One of the first engagements of the War of 1812, the Siege of Fort Mackinac was conducted by British and Native American. They captured the island soon after the outbreak of war between Britain and the United States. Encouraged by the easy British victory, more Native Americans subsequently rallied to their support. Native American cooperation was an important factor in several British victories during the remainder of the war. For the rest of 1812 and 1813, the British hold on Mackinac was secure since they also held Detroit, the territorial capital, which the Americans would have to recapture before attacking Mackinac. After the September 1813 Battle of Lake Erie, the British abandoned Detroit leaving an opportunity for the Americans try to retake the waters of Northern Michigan. In July 1814, as Commander of Fort Mackinaw Robert McDouall was struggling to supply war efforts Siege of Prairie du Chien, Americans attacked Mackinaw in July 1814 during the Battle of Mackinac Island. The Americans failed to take over the post, and the British held Mackinac Island until the peace in 1815, after which it was re-occupied by the US.[32][33]

Mackinac Island continued to be a locus of trade for the American Fur Company and was the site where Army doctor William Beaumont became Post surgeon[34] in 1820[35] and began conducting his famous digestion experiments on 19-year-old Alexis St. Martin between 1822 and 1833.[36][37] Mackinac Island was also the site where Henry Schoolcraft located his US Indian Agent headquarters starting in 1833. Following the 1830 Indian Removal Act, Schoolcraft negotiated the 1836 Treaty of Washington which opened up the land north of Grand Rapids for unequivocal legal ownership and settlement of lands in Northern Michigan, with provision that land sales would provide some monetary means to fund skills training for the Natives to assimilate to "civilized" life.

Despite the presence of fur trade, US military and Indian offices, and various tradesmen, the settled population of Michilimackinac (defined as all the settlements from Saginaw to Green Bay) was between 800 and 1000 for the time period between 1820 and 1840.[38]

Early coastal settlements in the 1830s through 1850s

.jpg.webp)

Decline of Mackinaw and fur trade

By the 1840s, the American Fur Company was in steep decline as silk hats replaced beaver hats in European fashion.[39][40] The straits of Mackinac declined in influence as government offices moved towards the capital at Detroit. While fishing slightly increased, the loss of the fur industry dealt a blow to Michilimackinac's economic significance.[41]

Increased ship traffic along Northern Michigan coasts

The Erie Canal opened in 1825, allowing settlers from New England and New York to reach Michigan by water through Albany and Buffalo. This route opening and the incorporation of Chicago in 1837,[42] increased Great Lakes steamboat traffic from Detroit through the straits of Mackinac to Chicago.[43][44][45] While the coastal areas were travelled, practically nothing was known about the interior parts of Northern Michigan.[46] When Michigan became a state in 1837, one of its first acts was to name Douglass Houghton as the lead of the Michigan Geological Survey, an effort to understand the geological and mineralogical, zoological, botanical, and topographical aspects of the lesser known parts of Michigan.[47] Early settlers came to the coasts along Northern Michigan, including fishermen, missionaries to the Native Americans, and participants in early Great Lakes maritime industries such as fishing, lighthouses, and cutting cordwood for passing ships. In 1835, Lieutenant Benjamin Poole of the 3rd U.S. Artillery.[48] surveyed a former Indian path between Saginaw and Mackinac that would become known as the Mackinac Trail.

Indian missions

Missions to Native Americans included Rev. Peter Dougherty[49] and Rev. John Fleming's 1839 Presbyterian mission on the Old Mission Peninsula, William Montague Ferry's Presbyterian-affiliated 1825 Mission House / Mission Church on Mackinac Island, Magdelaine Laframboise and Samuel Charles Mazzuchelli's Catholic Sainte Anne Church on Mackinac Island in 1830, Frederic Baraga Francis Xavier Pierz and Ignatius Mrak's Catholic mission to the people of the Chippewa and Ottawa at L'Arbre Croche and Peshawbestown (on the Leelanau Peninsula), Peter Greensky's Methodist Greensky Hill church founded near the Little Traverse Bay in 1844, and an 1848 congregationalist mission founded by Chief Peter Waukazoo and Reverend George Smith in Northport (on the Leelanau Peninsula). The Strangite Mormon community move to Beaver Island in 1848 [50] brought additional conflicts as the Mormon leaders sought to enforce laws and restrict use of alcohol on the Beaver Archipelago.[51]

Fishing settlements

Key fishing settlements included "Fishtown" in Leland, Michigan, and the Beaver Island Archipelago.

Lighthouses

Early Northern Michigan lighthouses included Thunder Bay Island Light (1831), Old Presque Isle Light (1840), South Manitou Island Lighthouse (1840), DeTour Reef Light (1847), Waugoshance Light (1851), Grand Traverse Light (1852), Tawas Point Light (1853), Beaver Island Harbor Light (1856), Beaver Island Head Light (1858), and Point Betsie Light (1858).

While the United States Lifesaving Service did not establish a system of Great Lakes Lifeboat stations on the Great Lakes until the 1870s,[52] some volunteer stations, such as the North Manitou Island Lifesaving Station were created as early as 1854.

Tension between White settlement and Native American land claims

In the 1836 Treaty of Washington, Michigan tribes ceded claims to land in Northern Michigan—and opened it to settlement. In the 1840s, Odawa villages lined the Lake Michigan shore, especially from present-day Harbor Springs to Cross Village. The area on the tip of the peninsula was mostly reserved for native tribes by treaty provisions with the U.S. federal government until 1875. Early government had been centered around Mackinac Island and St. Ignace, but between 1840 and 1853, the state broke up this single large Michilimackinac County[53][54][55][56] and established names and boundaries of about 21 counties across Northern Michigan. This naming and surveying allowed specific platted lands to be sold at the Land Office.[57] Increased white immigration and homesteading in Northern Michigan brought difficulties in dispatching of Native American land claims stemming from the treaty of 1836. Bands of Chippewa and Odawa Indians sought redress through the Treaty of 1855;[58] by this 1855 treaty agreement, lands and payments would be set aside for individual Native American families related to the 1836 treaty, but after this treaty, the US would cease to owe anything ("land, money or other thing guaranteed to them") to Indians or their tribes.[59]

1860s to 1890s: Homestead Act settlements and industrial developments

Increased settlement and establishment of port cities

Now that the land was surveyed and outstanding native land claims eliminated, Northern Michigan settlement increased even further. The Homestead Act of 1862 brought many Civil War veterans and speculators to Northern Michigan, by making 160 acre tracts of land available for $1.25 an acre.[60] The cutting of wood for passing ships morphed into a full-fledged lumber industry, contributing to the rise of port cities like Manistee, Traverse City, Charlevoix, and Ludington.

1870s: Arrival of rail infrastructure, rampant lumbering and fishing, and economic slowdown

Starting in the 1870s, railroads were built connecting Northern Michigan to larger industrial areas to the south. The Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad reached Traverse City in December 1872 (via Walton Junction and Traverse City Rail Road Company) and reached Petoskey (known up to that point as "Bear River") in 1873.[62] The Flint and Pere Marquette Railroad completed its terminal at Ludington in 1874. While the Michigan Central Railroad reached Otsego County in the fall of 1872,[63] rail investments slowed for several years due to the financial panic of 1873 and the ensuing five year economic slowdown. Cheboygan and [64] Mackinaw City did not have rail service until the early 1880s.[65]

Despite setbacks from the Great Michigan Fire in 1871 in Manistee and other lumbering ports, lumbering in Northern Michigan greatly increased. New mechanical tools such as steam-powered (versus water-powered) sawmills and circular saws expanded the ability to process high volumes of lumber quickly. Narrow-gauge moveable rails made it possible to harvest timber year round, in previously inaccessible places away from rivers.[66] The Michigan lumber market experienced a crash in July 1877 [67][68] that coincided with the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. By 1880 the Great Lakes region would dominate logging, with Michigan producing more lumber than any other state.[69]

The commercial fishing industry also flourished in the 1880s. By 1881, the rich fishing areas around the Beaver Archipelago led to Beaver Island becoming the largest supplier of fresh-water fish in the United States.[70] By 1886, there was a drastic reduction in the amount of fishing produced, due to overfishing.[71] In 1893, the Michigan Fish Commission commissioned the University of Nebraska Zoologist Henry Ward to study the sources of food for Traverse Bay area fish.[72]

_(14751712302).jpg.webp)

The passenger pigeon was hunted in Northern Michigan as a source of food, but by the 1870s, a combination of increased population and economic scarcity led to over-hunting and eventual extinction. The massive flocks of passenger pigeons stopped darkening the skies of Northern Michigan, especially after the last large scale nestings and subsequent slaughters of millions of birds in 1874 and 1878. By this time, large nestings only took place in the north, around the Great Lakes. The last large nesting was in Petoskey, Michigan, in 1878 (following one in Pennsylvania a few days earlier), where 50,000 birds were killed each day for nearly five months. The surviving adults attempted a second nesting at new sites, but were killed by professional hunters before they had a chance to raise any young. Scattered nestings were reported into the 1880s, but the birds were now weary, and commonly abandoned their nests if persecuted.[73]

1880s: Emergence of resort and vacation industry

Rail connections to the large midwestern cities through rail centers like Kalamazoo led to settlers immigrating and wealthy resorters establishing summer home associations in Bay View Association near Petoskey, the Belvedere Club in Charlevoix, and other lakeside getaways. Starting in 1875 (until 1895) the 1,044-acre (422 ha) Mackinac National Park became the second National Park in the United States after Yellowstone National Park in the Rocky Mountains.

Sport fishing

Sport fishing along the Au Sable River became a tourist attraction for wealthy sportsmen from Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Buffalo, Toledo, Indianapolis, and Chicago.[75] After the Jackson, Lansing and Saginaw Railroad reached Grayling in the late 1870s, it began to advertise hunting and fishing trips in Crawford County, home of the arctic grayling.[75] In the same way, the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railway published a "Guide to the Health, Pleasure, Game and Fishing Resorts of Northern Michigan reached by the Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad" in 1882.[76] In 1880, Ansel Judd Northrup, a lawyer from New York, published a detailed account of his train trip to fish Northern Michigan, and he assessed the Au Sable, Manistee River, Cheboygan River, Pigeon River, and Jordan River for trout and grayling fishing.[77] The state of Michigan, having created a Board of Fish Commissioners in 1873, stocked rivers with whitefish, black bass, and non-native species such as California salmon, California trout, German carp, and brook trout.[78] The Board of Fish Commissioners created its first fish hatchery at Crystal Springs Creek in Pokagon and shipped rail cars full of small fish to streams across Michigan.[79][80] As the grayling vanished from the Au Sable, Manistee and other rivers, the state propped up the Northern Michigan fishing industry with non-native brook trout, brown trout, and rainbow trout (steelhead).[81] Ultimately, the Arctic grayling that had inhabited much of Northern Michigan[82] was eventually wiped out. The logging practice of using river beds to move logs in the springtime destroyed the breeding grounds for these fish.[83] Before they could recover, non-native sport fish such as brook trout[84] took over the grayling's habitat and made them disappear from northern Michigan.

Industrial growth and diversification

The effect of rail connections was ultimately transformative; timber and other goods could be produced in the north and shipped to urban markets to the south. Diverse industries developed, such as iron works, tanneries, mills, cement plants, and agricultural enterprises. By 1885, the intense harvesting and export of pine trees led to visible decline in the lumber industry's ability to produce white pine.[85] Logging in Michigan peaked in 1889.[86] Where available, hardwoods and hemlock were harvested, temporarily extending the life of lumbering in the area, especially around East Jordan, the Traverse Bay, and near Crawford County.[87] William Howard White's lumber railroad (Boyne City, Gaylord & Alpena Railroad Company), David Ward's Detroit and Charlevoix Railroad, and the East Jordan and Southern Railroad enabled access to remote timber areas. As lumbering declined, rail lines began to promote Northern Michigan as a "fresh air" resort destination,[88] and the logging companies promoted their cut-over, stump-filled tracts for their agricultural potential.[89]

20th century: resort era

Early resorts

The resort era flourished in lakeside areas of Northern Michigan even as the fishing and lumbering industries experienced slow decline. Historian Bruce Catton's memoir Waiting for the Morning Train (1972) documents his personal experiences of early 20th-century life in a small Northern Michigan town as Michigan's logging era was ending.[90] Ernest Hemingway also documented turn-of-the-century life in Northern Michigan through his "Nick Adams" stories; Hemingway's own parents were resorters, wintering in Oak Park, Illinois, but summering in the Windemere cottage on Walloon Lake starting in 1899.[91]

State parks

As lumbering died down, many parts of Northern Michigan returned to their forested state through conservation efforts. The Huron National Forest was set aside in 1909. and the Manistee National Forest was set aside in 1938. State parks were established as well, to include:

- Interlochen State Park (1917)

- Mitchell State Park (1919)

- Burt Lake State Park (1920)

- Traverse City State Park (1920)

- Orchard Beach State Park (1921)

- Harrisville State Park (1921)

- Hoeft State Park (1922)

- Aloha State Park (1923)

- Straits State Park (1924)

- South Higgins Lake State Park (1927)

- Hartwick Pines State Park (1927)

- Wilderness State Park (1928)[92]

- Cheboygan State Park (1962) [93]

- Negwegon State Park (1962)

- Leelanau State Park (1964)

- North Higgins Lake State Park (1965)

- Clear Lake State Park (1966)

- Tawas Point State Park (1966)

- Petoskey State Park (1970)

- Fisherman's Island State Park (1975)

- Thompson's Harbor State Park (1988)

- Rockport State Park (2012)

Ski resorts

Hanson Hills in Grayling was the first downhill ski area in Michigan. It opened in 1929 and was served by rail service.[94]Caberfae Peaks Ski & Golf Resort near Cadillac opened in 1938 and was served by rail service. Boyne Mountain Resort opened in 1948. Crystal Mountain in Benzie County opened in 1956. Nub's Nob opened in 1958 near Harbor Springs.

Decline of rail

As passenger railroad usage ended in the 1960s (due in part to increased automobile travel), aggressive promotion of Northern Michigan by local chambers of commerce led to many of the festivals and attractions that bring visitors north even today.

Geography

Boundary description

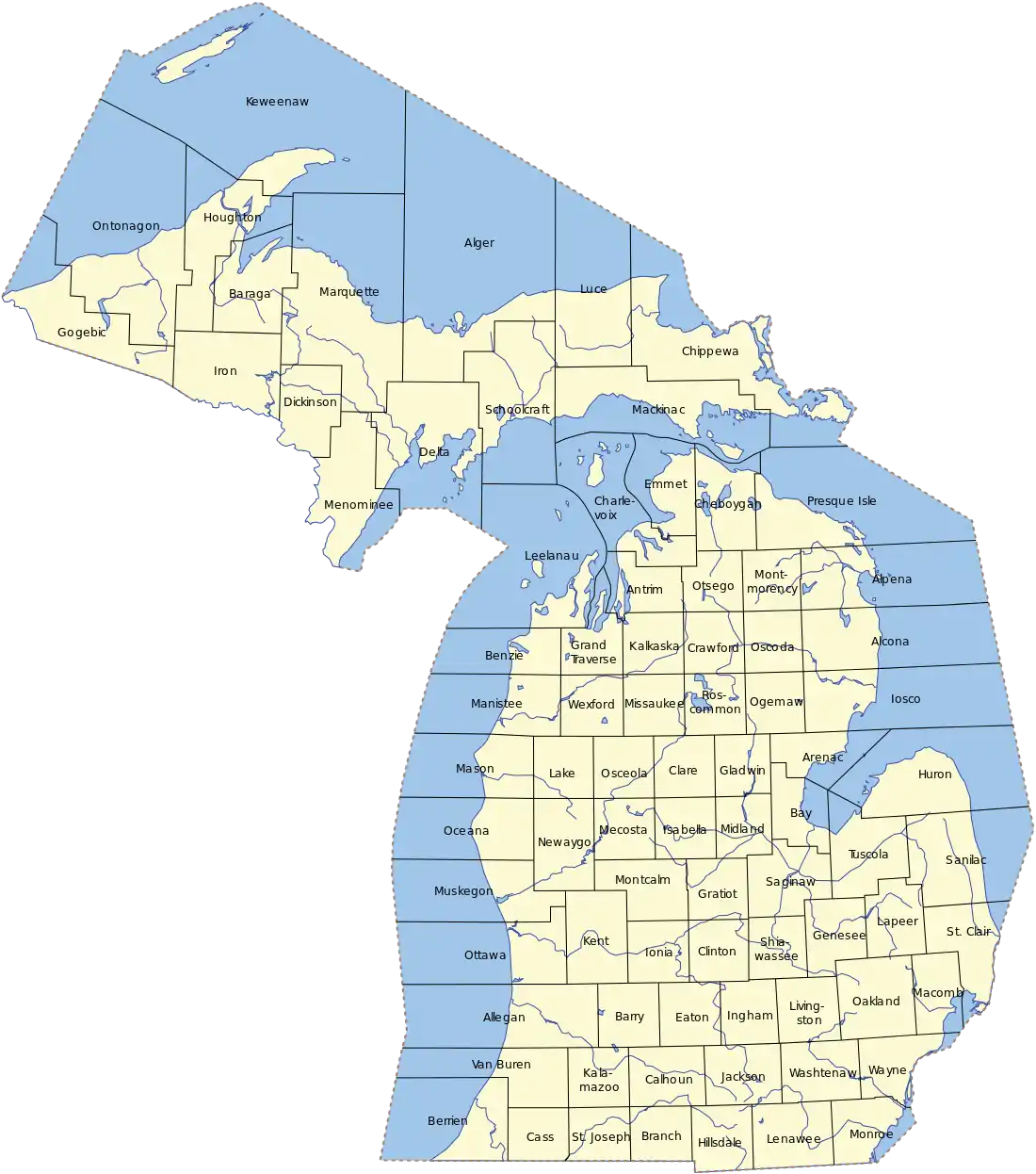

Residents of Northern Michigan generally consider it to lie between Grayling and the Mackinac Bridge. The southern boundary of the region is not precisely defined. Some residents in the southern part of the state consider its southern limit to be just north of Flint, Port Huron, Grand Rapids, or Mount Pleasant, though those in Northern Michigan refer to this are as Mid Michigan. Others may restrict it to the area north of Bay City and Clare, using US Highway 10 as a reference point, which roughly marks the "fingers" of the mitten-like shape of the Lower Peninsula.[95] The topic of where "Up North" begins is often debated among Michiganders, with there being no definitive answer on the subject.[96]

The 45th parallel runs across Northern Michigan. Signs in the Lower Peninsula that mark that line are at Mission Point Light[97] (just north of Traverse City); Suttons Bay; Cairn Highway in Kewadin;[98] Alba, Michigan, on U.S. 131 Highway (approximately two miles north of County Road 42, with signs on both sides of the highway); Gaylord;[99] Atlanta; and Alpena.[100] These are six of 29 places in the U.S.A. where such signs or monuments are known to exist. One other such sign is in Menominee, Michigan, in the Upper Peninsula.[101]

Definition excludes the Upper Peninsula

Across the Straits of Mackinac, to the north, west, and northeast, lies the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (the "U.P."). Despite its geographic location as the most northerly part of Michigan, the Upper Peninsula is not usually included in the definition of Northern Michigan (although Northern Michigan University is located in the U.P. city of Marquette), and is instead regarded by Michigan residents as a distinct region of the state, although residents of the Upper Peninsula often say that "Northern Michigan" is not in the Lower Peninsula. They insist the region must only be referred to as "Northern Lower Michigan", and this can sometimes become a topic of contention between people who are from different Peninsulas. The two regions are connected by the 5-mile-long Mackinac Bridge.[102] Those living South of the bridge are known as trolls, while those living above the bridge are yoopers.

Other definitions of Northern Michigan

All of the northern Lower Peninsula – north of a line from Manistee County on the west to Iosco County on the east (the second orange tier up on the map) – is considered to be part of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Gaylord.[103]

Topography, climate and soil

The geographical theme of this region is shaped by rolling hills, Great Lakes shorelines including coastal dunes on the west coast, large inland lakes, numerous rivers and large forests. A tension zone is identified running from Muskegon to Saginaw Bay marked by a change in soil type and common tree species.[104] North of the line the historic presettlement forests were beech and sugar maple, mixed with hemlock, white pine, and yellow birch which only grew on moist soils further south. Southern Michigan forests were primarily deciduous with oaks, red maple, shagbark hickory, basswood and cottonwood which are uncommon further north. Northern Michigan soils tend to be coarser, and the growing season is shorter with a cooler climate. Lake effect weather brings significant snowfalls to snow belt areas of Northern Michigan.

Glaciers shaped the area, creating a unique regional ecosystem. A large portion of the area is the so-called Grayling outwash plain, which consists of broad outwash plain including sandy ice-disintegration ridges; jack pine barrens, some white pine-red pine forest, and northern hardwood forest. Large lakes were created by glacial action.[105]

Weather

The region has the four seasons in their extremes, with sometimes hot and humid summer days (although, mild in comparison to some parts of the south) to subzero days in winter. With the expansive hardwood forest in Northern Michigan, "fall color" tourists are found throughout the area in early to mid-autumn.[106] When the spring rains come, many roads and bridges become impassable due to flooding or muddy to the point a four-wheel drive cannot pass. Snowfall varies throughout the region due to lake-effect snow from the prevailing westerly winds off of Lake Michigan: average yearly snow ranges from 141.4 inches or 3.59 metres in Gaylord to 52.4 inches or 1.33 metres in Harrisville.[107] Both the high and low temperature records for all of Michigan are held by communities in Northern Lower Michigan. The high is 112 °F or 44.4 °C set in Mio on July 13, 1936, and the low is −51 °F or −46.1 °C set in Vanderbilt on February 9, 1934.[108]

Population

.jpg.webp)

In the northernmost 21 counties in the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, the total population of the region is 506,658 people.[upper-alpha 1] The most populated city in Northern Michigan is Traverse City, with over 15 thousand inhabitants. Grand Traverse County is the largest county in Northern Michigan by population, at just under 100,000. Grand Traverse County also contains the three most populous municipalities in Northern Michigan: Garfield Township, Traverse City (which partially extends into Leelanau County), and East Bay Township.

| Municipality | 2020 population | Area (sq mi) | Area (km2) | County(ies) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traverse City | 15,678 | 8.66 | 22.43 | Grand Traverse, Leelanau |

| Cadillac | 10,371 | 8.91 | 23.09 | Wexford |

| Alpena | 10,197 | 9.23 | 23.9 | Alpena |

| Ludington | 8,076 | 3.60 | 9.34 | Mason |

| Manistee | 6,259 | 4.53 | 11.73 | Manistee |

| Petoskey | 5,877 | 5.34 | 13.84 | Emmet |

| Houghton Lake | 5,294 | 7.49 | 19.4 | Roscommon |

| Cheboygan | 4,876 | 6.93 | 17.94 | Cheboygan |

| Gaylord | 4,286 | 5.00 | 12.95 | Otsego |

| Boyne City | 3,816 | 5.34 | 13.84 | Charlevoix |

| Clare | 3,254 | 3.83 | 9.92 | Clare, Isabella |

| Skidway Lake | 3,082 | 11.79 | 30.52 | Ogemaw |

| Gladwin | 3,069 | 2.90 | 7.51 | Gladwin |

| Rogers City | 2,850 | 8.36 | 21.65 | Presque Isle |

| St. Helen | 2,735 | 5.92 | 15.3 | Roscommon |

| East Tawas | 2,663 | 3.27 | 8.48 | Iosco |

| Reed City | 2,490 | 2.13 | 5.53 | Osceola |

| West Branch | 2,351 | 1.53 | 3.97 | Ogemaw |

| Charlevoix | 2,348 | 2.05 | 5.30 | Charlevoix |

| East Jordan | 2,239 | 3.92 | 10.15 | Charlevoix |

| Harrison | 2,150 | 4.03 | 10.43 | Clare |

| Kalkaska | 2,132 | 3.21 | 8.31 | Kalkaska |

| Indian River | 1,950 | 20.2 | 52.4 | Cheboygan |

| Tawas City | 1,834 | 2.13 | 5.51 | Iosco |

| Grayling | 1,867 | 2.08 | 5.39 | Crawford |

| Evart | 1,742 | 2.53 | 6.55 | Osceola |

| Mio | 1,690 | 8.98 | 23.3 | Oscoda |

| Prudenville | 1,643 | 3.62 | 9.4 | Roscommon |

| Elk Rapids | 1,642 | 2.01 | 5.20 | Antrim |

| Greilickville | 1,634 | 7.11 | 18.41 | Leelanau |

| Standish | 1,458 | 2.18 | 5.64 | Arenac |

| Au Sable | 1,453 | 2.13 | 5.52 | Iosco |

| Kingsley | 1,431 | 1.22 | 3.17 | Grand Traverse |

| Rapid City | 1,357 | 5.53 | 14.31 | Kalkaska |

| Mancelona | 1,344 | 1.00 | 2.60 | Antrim |

| Harbor Springs | 1,274 | 1.29 | 3.35 | Emmet |

| Manton | 1,258 | 1.61 | 4.18 | Wexford |

| Frankfort | 1,252 | 1.58 | 4.10 | Benzie |

| Scottville | 1,214 | 1.49 | 3.86 | Mason |

| Beaverton | 1,145 | 1.33 | 3.44 | Gladwin |

| Chums Corner | 1,065 | 2.79 | 2.66 | Grand Traverse |

| Bellaire | 1,053 | 1.99 | 5.16 | Antrim |

| Lakes of the North | 1,044 | 16.73 | 43.44 | Antrim |

The area was populated by many different ethnicities, including groups from New England (Maine, Vermont, New York), Ireland, Germany, and Poland. The Odawa nation is located in Emmet County (Little Traverse Band of Odawa Indians). Other Native American reservations exist at Mount Pleasant and on the Leelanau Peninsula.

Counties

There are 21 counties traditionally associated with Northern Michigan:

| County | 2020 population | Land area (sq mi) | Land area (km2) | Seat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcona County | 10,167 | 675 | 1,750 | Harrisville |

| Alpena County | 28,907 | 572 | 1,480 | Alpena |

| Antrim County | 23,431 | 476 | 1,230 | Bellaire |

| Benzie County | 17,970 | 320 | 800 | Beulah |

| Charlevoix County | 25,597 | 416 | 1,080 | Charlevoix |

| Cheboygan County | 26,152 | 715 | 1,850 | Cheboygan |

| Crawford County | 23,988 | 556 | 1440 | Grayling |

| Emmet County | 34,112 | 467 | 1,210 | Petoskey |

| Grand Traverse County | 95,238 | 464 | 1,200 | Traverse City |

| Iosco County | 25,237 | 549 | 1,420 | Tawas City |

| Leelanau County | 22,301 | 347 | 900 | Suttons Bay |

| Kalkaska County | 17,939 | 560 | 1,500 | Kalkaska |

| Manistee County | 25,032 | 542 | 1,400 | Manistee |

| Missaukee County | 15,052 | 565 | 1,460 | Lake City |

| Montmorency County | 9,153 | 547 | 1,420 | Atlanta |

| Ogemaw County | 20,770 | 563 | 1,460 | West Branch |

| Oscoda County | 8,219 | 566 | 1,470 | Mio |

| Otsego County | 25,091 | 514 | 1,330 | Gaylord |

| Presque Isle County | 12,982 | 659 | 1,710 | Rogers City |

| Roscommon County | 23,459 | 520 | 1,300 | Roscommon |

| Wexford County | 33,673 | 565 | 1,460 | Cadillac |

In addition to these 21, six more counties to the south are also occasionally referred to as Northern Michigan, but are generally considered to be part of other regions. This counties are:

| County | 2020 population | Land area (sq mi) | Land area (km2) | Seat |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arenac County | 15,002 | 363 | 1,760 | Standish |

| Clare County | 30,856 | 564 | 1,460 | Harrison |

| Gladwin County | 25,386 | 502 | 1,300 | Gladwin |

| Lake County | 12,096 | 567 | 1,470 | Baldwin |

| Mason County | 29,052 | 495 | 1,280 | Ludington |

| Osceola County | 22,891 | 566 | 1,470 | Reed City |

Cities, villages, and unincorporated communities

Below is a list of cities, villages, and unincorporated communities in northern Michigan:

- Acme (Grand Traverse)

- Afton (Cheboygan)

- Albert (Montmorency)

- Albert (Emmet)

- Aloha (Cheboygan)

- Alpena (Alpena)

- Arlene (Missaukee)

- Atlanta (Montmorency)

- Au Gres (Arenac)

- Barton City (Alcona)

- Bates (Grand Traverse)

- Beaver Island (Charlevoix)

- Beaverton (Gladwin)

- Bear Lake (Manistee)

- Belknap (Presque Isle)

- Benzonia (Benzie)

- Beulah (Benzie)

- Black River (Alcona)

- Boon

- Boyne City (Charlevoix)

- Boyne Falls (Charlevoix)

- Briley (Montmorency)

- Brookside (Grand Traverse)

- Buckley (Wexford)

- Cadillac (Wexford)

- Cedar (Leelanau)

- Central Lake (Antrim)

- Charlevoix (Charlevoix)

- Cheboygan (Cheboygan)

- Custer (Mason)

- Denton (Roscommon)

- East Jordan (Charlevoix)

- East Tawas (Iosco)

- Elberta (Benzie)

- Elk Rapids (Antrim)

- Empire (Leelanau)

- Fairview (Oscoda)

- Falmouth (Missaukee)

- Fife Lake (Grand Traverse)

- Fountain (Mason)

- Frankfort (Benzie)

- Free Soil, Michigan (Mason)

- Gaylord (Otsego)

- Gladwin (Gladwin)

- Glennie (Alcona)

- Glen Arbor (Leelanau)

- Glen Haven (Leelanau)

- Goodar (Ogemaw)

- Good Harbor (Leelanau)

- Grawn (Grand Traverse)

- Grayling (Crawford)

- Greenbush (Alcona)

- Greilickville

- Gustin (Alcona)

- Hale (Iosco)

- Hannah (Grand Traverse)

- Harbor Springs (Emmet)

- Harrietta

- Harrisville (Alcona)

- Hawks (Presque Isle)

- Herron (Alpena)

- Higgins Lake (Roscommon)

- Hillman (Alpena/Montmorency)

- Honor (Benzie)

- Houghton Lake (Roscommon)

- Hubbard Lake (Alcona)

- Indian River (Cheboygan)

- Interlochen (Grand Traverse)

- Kalkaska (Kalkaska)

- Kaleva (Manistee)

- Karlin (Grand Traverse)

- Kingsley (Grand Traverse)

- Lachine (Alpena)

- Lake Ann (Benzie)

- Lake City (Missaukee)

- Lake Leelanau (Leelanau)

- Leland

- Lewiston (Montmorency)

- Lincoln (Alcona)

- Long Rapids (Alpena)

- Lost Lake Woods (Alcona)

- Ludington (Mason)

- Lupton (Ogemaw)

- Mackinac Island (Mackinac)

- Mackinaw City (Cheboygan/Emmet)

- Manistee (Manistee)

- Manton (Wexford)

- Mapleton (Grand Traverse)

- Maple City (Leelanau)

- Maple Ridge (Arenac)

- Mayfield (Grand Traverse)

- McBain (Missaukee)

- Mesick (Wexford)

- Metz (Presque Isle)

- Millersburg (Presque Isle)

- Mikado (Alcona)

- Mio (Oscoda)

- Moltke (Presque Isle)

- Monroe Center (Grand Traverse)

- Mullett Lake (Cheboygan)

- National City (Iosco)

- Northport (Leelanau)

- Ocqueoc (Presque Isle)

- Ogdensburg (Grand Traverse)

- Old Mission (Grand Traverse)

- Omena (Leelanau)

- Omer (Arenac)

- Onaway (Presque Isle)

- Onekama (Manistee)

- Oscoda (Iosco)

- Ossineke (Alpena)

- Palaestrum (Grand Traverse)

- Pellston (Emmet)

- Petoskey (Emmet)

- Posen (Presque Isle)

- Prescott (Ogemaw)

- Presque Isle (Presque Isle)

- Prudenville (Roscommon)

- Rapid City (Kalkaska)

- Richfield (Roscommon)

- Rogers City (Presque Isle)

- Roscommon (Roscommon)

- Rose City (Ogemaw)

- Rust (Montmorency)

- St. Helen (Roscommon)

- Scottville (Mason)

- South Boardman (Kalkaska)

- South Branch (Iosco)

- Spruce (Alcona)

- Standish (Arenac)

- Sterling (Arenac)

- Summit City (Grand Traverse)

- Tawas City (Iosco)

- Thompsonville (Benzie)

- Topinabee (Cheboygan)

- Tower (Cheboygan)

- Traverse City (Grand Traverse/Leelanau)

- Turner (Arenac)

- Twining (Arenac)

- Vanderbilt (Otsego)

- Walhalla (Mason)

- Walton (Grand Traverse/Wexford)

- West Branch (Ogemaw)

- Whittemore (Iosco)

- Wilber (Iosco)

- Williamsburg (Grand Traverse)

- Wolverine (Cheboygan)

- Yuba (Grand Traverse)

Indian reservations

- Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians

- Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians

- Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians occupies at least 13 scattered reservation areas within Emmet County, including portions within the city of Petoskey and the townships of Bear Creek, Bliss, Center, Little Traverse, McKinley, Readmond, Resort, Wawatam, and West Traverse.[109]

- Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians

Flora and fauna

Common plants

Northern Michigan has many tree types including maple, birch, oak, ash, white cedar, aspen, pine, and beech. Ferns, milkweed, Queen Anne's lace, and chicory grow in the open fields and along roadsides. Forest plants include wild leeks, morel mushrooms, and trilliums. Marram grass grows on beaches. Several mosses cover the land.

Common mammals

Common mammals in Northern Michigan include white-tailed deer, fox, raccoons, porcupines, and rabbits. black bear, elk, coyote, bobcat, wolves, and mountain lions are also present. Although not common, the presence of cougars has been persistently reported over many years.[110][111][112] Fish include whitefish, yellow perch, trout, bass, northern pike, walleye, muskie, and sunfish.

Common birds

Common birds are ducks, seagulls, wild turkey, great blue herons, northern cardinals, blue jays, black-capped chickadees, hummingbirds, Baltimore oriole, and ruffed grouse. Canada geese may be seen flying over head in spring and fall. Less well known birds that are unique in Michigan to the Northern Lower Peninsula are spruce grouse, sharp-tailed grouse, red-throated loon, Swainson's hawk, and the boreal owl.[113][114]

The Au Sable State Forest is a state forest in the north-central Lower Peninsula of Michigan. Much of the forest is used for wildlife game management and the fostering of endangered and rare species, such as the Kirtland's warbler – there are regular controlled burns to maintain its habitat. The Kirtland's warbler has its habitat in an increasing part of the area.[115] There is a Kirtland's Warbler Festival, which is sponsored in part by Kirtland Community College.[116]

The American Bird Conservancy and the National Audubon Society have designated several locations as internationally Important Bird Areas.[117]

Common insects

Insect populations are similar to those found elsewhere in the midwestern United States. ladybugs, crickets, dragonflies, mosquitoes, ants, house flies, and grasshoppers are common, as is the Western conifer seed bug, and several kinds of butterflies and moths (for example, monarch butterflies and tomato worm moths). Notable deviations in insect populations are a high population of June bugs during June as well as a scarcity of lightning bugs because of the lower average temperatures year round and especially in the summer.

Northern Michigan is home to Michigan's most endangered species and one of the most endangered species in the world: the Hungerford's crawling water beetle. The species lives in only five locations in the world, four of which are in Northern Michigan (one is in Bruce County, Ontario). Indeed, the only stable population of the rare beetle occurs along a two and a half mile stretch of the East Branch of the Maple River in Emmet County, Michigan.

Common reptiles

There are no fatally venomous snakes native to Northern Michigan. The venomous Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake lives in Michigan, but it is not common, particularly in Northern Michigan. In any event, its non-fatal bite may make an adult sick, but it should be medically treated without delay.

Snakes present include the eastern hog-nosed snake, brown snake, common garter snake, eastern milk snake and the northern ribbon snake. The only common reptiles and amphibians are various pond frogs, toads, salamanders, and small turtles.

State Forests and conservation areas

The state forests in the U.S. state of Michigan are managed by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Forest, Mineral and Fire Management unit. It is the largest state forest system in the nation at 3,900,000 acres (16,000 km2). See List of Michigan state forests. The Northern lower peninsula includes three forests:

- Mackinaw State Forest

- Atlanta FMU (Alpena, northeast Cheboygan, most of Montmorency, and most of Presque Isle counties)

- Gaylord FMU (Antrim, Charlevoix, most of Cheboygan, Emmet, and most of Otsego counties)

- Pigeon River Country FMU (southeast Cheboygan, northwest Montmorency, northeast Otsego, and southwest Presque Isle counties)

- Pere Marquette State Forest

- Cadillac FMU (Lake, Mason, Mecosta, Missaukee, Newaygo, Oceana, Osceola, and Wexford counties)

- Traverse City FMU (Benzie, Grand Traverse, Leelanau, Kalkaska, Manistee counties)

- Au Sable State Forest

- Gladwin FMU (Arenac, Bay, Clare, Gladwin, southern Iosco, Isabella, and Midland counties)

- Grayling FMU (Alcona, Crawford, Oscoda, and northern Iosco counties)

- Roscommon FMU (Ogemaw and Roscommon counties)

In addition, large portions of this area are covered by the Manistee National Forest and the Huron National Forest. In the former, a unique environment is present at the Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness. This relatively small area of 3,450 acres (14.0 km2), on Lake Michigan's east shore, is one of few wilderness areas in the U.S. with an extensive lake shore dunes ecosystem. The dunes are 3500 to 4000 years old, and rise to nearly 140 feet (43 m) higher than the lake. The Nordhouse Dunes are interspersed with woody vegetation such as jack pine, juniper and hemlock. Many small water holes and marshes dot the landscape, and dune grass covers some of the dunes. The wide and sandy beach is ideal for walks and sunset viewing.

Eight islands off the Lakes Michigan and Huron coasts – Charlevoix and Alpena counties, respectively – are part of the Michigan Islands National Wildlife Refuge.

Tourism

Summer destinations

Boating, golf, and camping are leading activities. Sailing, kayaking,[118] canoeing, birding, bicycling,[119][120][121] horse back riding, motorcycling, and 'off roading' are important avocations. The forest activities are available everywhere. There are a great many Michigan state parks and other protected areas which make these truly a 'pleasant peninsula.' These would include the Huron National Forest and the Manistee National Forest, plus the Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore (a 35-mile stretch of eastern Lake Michigan dunes)[122] and the Nordhouse Dunes Wilderness.

- Many city dwellers from "downstate" and nearby areas (notably Chicago) have summer vacation homes in Northern Michigan. The largest resort cities in Northern Michigan are in the west on Lake Michigan, with its sandy beaches and warm bays. Popular tourist towns in Northern Michigan include Northport, Traverse City, Elk Rapids, Charlevoix, Boyne City, Petoskey, Manistee, Ludington, Bear Lake, Empire, Frankfort,[123] Harbor Springs, and Leland. It should also be noted that there is a large wine district in the area along the Lake Michigan Shore.

- At the top of the lower peninsula are Mackinaw City, and Mackinac Island[124] (which lies between the Lower and Upper Peninsulas in the Straits of Mackinac).

- Less well known and less developed is the northeastern lower peninsula along the Lake Huron shore. It offers many great vacation spots, particularly along the coast. These are, in order from south-to-north, Standish, Omer, Au Gres, Tawas City, East Tawas, Oscoda, Greenbush, Harrisville, Alpena, Presque Isle, Rogers City, Cheboygan, and points in between. Some consider these to be more 'up north' than the relatively congested west coast. Indeed, the Detroit Free Press noted that the area between Oscoda and Ossineke included beaches that are "overlooked" and among the "top ten in Michigan." This would include the area around Harrisville (and two state parks). It was noted that: "Old-fashioned lake vacations abound on this pretty stretch of Lake Huron."[125]

- In between the two (or three, depending on how you count) coasts, there are a large number of inland cities and lakes (Michigan has 11,037 lakes), and a varied landscape that has many rivers. Such places as Cadillac, Kalkaska, Grayling, West Branch and Gaylord are also prized summer destinations for Michiganders and visitors from other states. Among many others, Houghton Lake, Higgins Lake, Torch Lake, and Hubbard Lake are large inland lakes within the region.

- The Michigan Shore to Shore Riding & Hiking Trail[126] runs from Empire to Oscoda, and points north and south. It is a 240-mile (390 km) interconnected system of trails.

- The Great Lakes Circle Tour is a designated scenic road system connecting all of the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River.[127]

Non-summer destinations

Some of the downhill and Nordic skiing (cross-country) resorts located in the Northern Lower include Boyne Mountain, Boyne Highlands, Otsego Club & Resort (since 1939), Crystal Mountain Resort, Snow Snake Ski and Golf, Nub's Nob, Caberfae Peaks and Schuss Mountain. Some of these also serve as summer golf resorts. Frederic, Michigan, is a particularly noteworthy center for cross country skiing.

Fall activities include harvest festivals, seasonal beer and wine events, and fall color tours. Hunting in Northern Michigan is a popular fall pastime. There are seasons for bow hunting and a muzzle-loader season as well as for using modern rifle season. The opening day of deer season (November 15) is a major day for some residents. Some schools close November 15, due to low attendance as a result of the opening day of deer season.

In winter, a variety of sports are enjoyed by the locals which also draw visitors to Northern Michigan. Snowmobiling, also called sledding, is popular, and with hundreds of miles of interconnected groomed trails cross the region. Ice fishing is also popular. Tip-up Town on Houghton Lake is a major ice-fishing, snowmobiling and winter sports festival, and is unique in that it is a village that assembles out on the frozen lake surface. Higgins Lake also offers good ice fishing and has many snowmobiling, cross country skiing, and snowshoeing trails at the North Higgins Lake State Park. Grayling and Gaylord and their environs are recognized for Nordic skiing. Cadillac is reputed to be even more popular during the winter than it is in the summer.

Other tourist attractions

- Pierce Stocking Scenic Drive

- Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary

- Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore

- Mackinac Bridge

- Boyne Mountain

- Fort Michilimackinac

- Many State Parks

The Lumberman's Monument honors lumberjacks that shaped the area, exploiting the natural resource. It is located on the River Road National Scenic Byway, which runs parallel with the Au Sable River, and is a designated National Scenic Byway for the 23 miles (37 km) that go into Oscoda.[128] The State of Michigan has designated Oscoda as the official home of Paul Bunyan due to the earliest documented publications in the Oscoda Press, August 10, 1906, by James MacGillivray (later revised and published in The Detroit News in 1910).[129]

Hartwick Pines State Park is a 9,672-acre (39.14 km2) state park and logging museum located in Crawford County near Grayling and I-75. It is the third largest state park on Michigan's Lower Peninsula and the state's fifth-biggest park overall. The park contains an old growth forest of white pines and red pines that resembles the appearance of all of Northern Michigan prior to the logging era. Also to be noted is Interlochen State Park, which is the oldest state park and the other remaining stand of virgin Eastern White Pine in the Lower Peninsula.

The Besser Museum for Northeast Michigan is a community museum serving Alpena County and surrounding counties in the U.S. state of Michigan. Alpena is a port city on Lake Huron. The museum defines its role broadly — to preserve, protect and present history and culture closely connected with the heritage of Northern Michigan and the Great Lakes. The museum includes a small publicly owned planetarium.[130] The institution says "Our mission is to collect, preserve, interpret, and exhibit authentic articles and artifacts of art, history, and science to inspire curiosity, foster community pride, and cultivate personal legacy."[131]

There were more than 150 past and present lighthouses around Michigan's Great Lakes coasts, including several in Northern Michigan. They serve as functioning warnings to mariners, but are also integral to the region's culture and history. See the list of Michigan lighthouses for more information on individual lighthouses.

Festivals

A number of annual festivals occur in Northern Michigan, including:

| Festival | Location | Remarks and sources |

|---|---|---|

| AlpenFest and Alpenfest run/walk | Gaylord | [132][133] |

| Art on the Beach | Oscoda | [134] |

| Arts and crafts shows around the state | Various | [135] |

| Bass Festival | Mancelona | [136][137] |

| Blissfest (folk festival) | Bliss Township | [138][139] |

| Cadillac Chestnut Harvest Festival | Cadillac | [140] Held every year, on the second Saturday of October[141] |

| Cedar Polka Festival | Cedar | [142] |

| Celebration Days at Tawas Point State Park | East Tawas, Michigan | [143] |

| Charlevoix Waterfront Art Fair | Charlevoix | [144] 2nd weekend in August |

| Chicago Yacht Club Race to Mackinac | Lake Michigan | [145] |

| Dulcimer FunFest | Evart | [146] |

| Firemen's Memorial Festival | Roscommon | [147] |

| Freedom Festival | East Jordan | [148] |

| Great Lakes Bioneers Conference | ??? | [149] |

| Great Lakes Lighthouse Festival | Alpena | [150] According to Tim Harrison, Editor in Chief and publisher of Lighthouse Digest magazine, and President of American Lighthouse Foundation, "There is no other festival like it in the United States..."[151] |

| Harrisville Arts & Crafts Show aka "Harmony Weekend"[152] | Harrisville | Labor Day weekend |

| Hoxeyville Music Festival | South Branch Township, Wexford County, Michigan | [153] |

| Kirtland Warbler Festival | Roscommon County, Michigan | [154] |

| Leland Wine & Food Festival | Northport | [155] |

| Mackinac Island Fudge Festival | Mackinac Island | [156] |

| Mackinac Island Lilac Festival | Mackinac Island | [157] |

| Mackinac Island Music Festival | Mackinac Island | [158] |

| Michigan Brown Trout Festival | Alpena | [159][160][161][162] |

| Mushroom Festival | Mesick | [163] |

| National Cherry Festival | Traverse City | [164] |

| National Coho Salmon Festival | Honor | [165] |

| National Forest Festival | Manistee | [166] |

| National Morel Mushroom Festival | Boyne City | [167] |

| National Trout Festival | Kalkaska | [168] End of April |

| Nautical Festival | Rogers City | [169] |

| North American Snowmobile Festival | Cadillac | [170] |

| Northport's Harbor Day (and July 4 Celebration) | Northport | |

| Paul Bunyan Festival & Great Lakes Chainsaw Carving Competition | Oscoda | [134] |

| Petoskey Festival on the Bay | Petoskey | [171] |

| Polish Festival | Boyne Falls | [172] |

| Port Huron to Mackinac Boat Race | Lake Huron | Ends on Mackinac Island [173] |

| Posen Potato Festival | Posen | [174] |

| Salmon Slam | Northport, Michigan | |

| Scottville Harvest Festival | Scottville | [175] |

| Timberfest | Lewiston | [176] |

| Tip-Up Town (ice fishing festival) | Houghton Lake | [177] |

| Traverse Bay Farms Salsa Bar Festival | Elk Rapids/Bellaire | [178] |

| Traverse City Film Festival | Traverse City | |

| Venetian Festival | Charlevoix | [179] |

| Weyerhauser Au Sable River Canoe Marathon | Grayling to Oscoda | One leg of the "Triple Crown of Canoe Racing". This is one of the few pro-am canoeing events in the U.S., and winning times may be as long as 21 hours.[180][181][182] |

| WinterFest and | Kalkaska | [183] Includes a sled dog race.[184] |

| World Famous Labor Day Fish Boil | Northport, Michigan |

Economy

The economy of Northern Michigan is limited by its lower population, few industries and reduced agriculture compared to lower Michigan. Seasonal and tourism related employment is significant. Unemployment rates are generally high. (In June 2007, seven of the ten highest unemployment rates occurred in counties in the Northern Michigan area.[185] Historically, Fur trade, lumbering and commercial fishing were among the most important industries. The fur trade essentially died out in the 1840s. Logging is still important but at a mere fraction of its heyday (1860–1910) output. Commercial fishing is a minor activity.

Vacation and tourism

A major draw to Northern Michigan is tourism. Real estate, especially condominiums and summer homes, is another significant source of income. Because money spent in the real estate and tourism market in Northern Michigan is dependent upon visitors from southern Michigan and the Chicago area, the Northern Michigan economy is sensitive to downswings in the automobile and other industries.[186]

Agriculture

Agriculture is limited by the climate and soil conditions compared to southern regions of the state. However, there are significant potato and dry bean farms in the east. Wine grapes, vegetables and cherries are produced in the west in the protected microclimates around Grand Traverse Bay. The Grand Traverse region has two of Michigan's four federally-recognized wine growing areas. The Grand Traverse Bay area is listed as one of the most endangered agricultural regions in the U.S. as its scenic land is highly sought after for vacation homes.

Heavy industry

Heavy industrial developments are sparse. The northeast corner has an industrial base.

Quarrying and mining

Cement-making and the mining of limestone and gypsum for Portland Cement are major exports of the area. Charlevoix's Medusa Cement Plant was bought by Cemex in the 1990s. Alpena is home to the Lafarge Company's holdings in the world's largest cement plant and is home to Besser Block Co. (Jesse M. Besser invented concrete block in 1904 and founded the Besser Block Co. in Alpena after making the concrete block making machine). USG Corporation, also known as United States Gypsum Corporation, operates several quarries, including one at Alabaster, and one in Rogers City. Rogers City is the locale of the world's largest limestone quarry, which is also used in steel making all along the Great Lakes.

Energy (oil and natural gas)

Northern Michigan has significant natural gas reserves along the Antrim shale formation in northern Michigan. By some estimates it is the 15th largest gas field in the nation.[188] Drilling activity peaked in the late 1980s and early 1990s,[189] In 2014, Encana, the Canadian company who had been drilling in Northern Michigan, sold their mineral rights to Marathon Oil order to focus on more profitable operations elsewhere. For oil interest, Encana amassed rights for the Collingwood-Utica Shale (Michigan) between 2008 and 2010, mostly in Cheboygan, Kalkaska, Michigan, and Missaukee counties. The Collingwood layer is two miles below the surface and would require horizontal drilling.[190][191][192]

Manufacturing

Alpena has a hardboard manufacturing facility owned by Decorative Panels, International. Nearer to the Lake Michigan shore, Cadillac and Manistee have manufacturing and chemical industries. Morton Salt operates one of the largest salt plants in the world in Manistee. Also, the East Jordan Iron Works corporate offices, as well as the original foundry, are located in East Jordan.

Maritime

A small number of people work on the Great Lakes freighters. Adjacent to the Traverse City Cherry Capital Airport is a United States Coast Guard air station (CGAS), which is responsible for both maritime and land-based search and rescue operations in the northern Great Lakes region.

Military

Military presence in Northern Michigan is as follows:

- Alpena Combat Readiness Training Center in Alpena, Michigan, is run by the Air National Guard and is co-located with the Alpena County Regional Airport.

- Camp Grayling near Grayling, Michigan. Camp Grayling is the largest military installation east of the Mississippi River, and the nation's largest National Guard training site. It is used by the U.S. National Guard, as well as active and reserve components of the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps. Year-round training is conducted on its 147,000 acres (590 km2) in Crawford, Kalkaska and Otsego counties. Much of the land (including Lake Margrethe) is accessible to the public for hunting, fishing, snowmobiling and other recreational uses (when military training is not happening).

- Wurtsmith Air Force Base near Oscoda closed in 1993 and has been converted to civilian use as Oscoda-Wurtsmith Airport.

- The Coast Guard has a presence in Charlevoix, Cheboygan, and Traverse City.

Education

Interlochen Center for the Arts is a notable arts center that offers a high-school-level academy and summer camp near Traverse City. There are also several institutions of higher education in Northern Michigan. Community colleges include North Central Michigan College (NCMC, pronounced "nuck-muck" by locals), Alpena Community College, Huron Shores Campus-Alpena Community College, Kirtland Community College, West Shore Community College, and Northwestern Michigan College (NMC) including the Great Lakes Maritime Academy, the only U.S. maritime academy on freshwater. Northern Michigan has arguably only one four-year university (depending on the definition of the southern boundary of the region), Ferris State University in Big Rapids. Other nearby universities are in the Upper Peninsula (Northern Michigan University and Lake Superior State University), as well as Central Michigan University and Ferris State University in the more southern reaches of the state. The University of Michigan runs the University of Michigan Biological Station out of Pellston, MI. Central Michigan University runs the CMU Biological Station on Beaver Island. Hillsdale College runs the biological station in Lake County.

Many four-year universities located downstate offer bachelor's and master's degree programs through Northwestern Michigan College's unique University Center program, located in Traverse City. The University Center, located in Traverse City, is a joint program with Northwestern Michigan College and various universities around the state that allows local students to "attend" universities that offer bachelor's and master's degrees programs not available through NMC, a two-year college, locally without leaving Northern Michigan. NMC supplies the facilities while the senior universities provide the education and endorsement. Universities offering programs here include Michigan State University, Western Michigan University, Central Michigan University, Grand Valley State University, Ferris State University, Spring Arbor University, and others.[193]

Media

Northern Michigan is in the Designated Market Areas of "Traverse City-Cadillac" (116), "Alpena" (208), and some portions of "Flint-Saginaw-Bay City" (66).

Newspapers

- Alcona County Review, Harrisville

- The Alpena News

- Boyne City Gazette

- Cadillac Evening News

- Charlevoix Courier

- Cheboygan Daily Tribune

- Citizen-Journal, Boyne City, East Jordan

- Crawford County Avalanche, Grayling

- Gaylord Herald Times

- Grand Traverse Herald, weekly in Traverse City

- Iosco County News-Herald, Tawas City

- The Leader and the Kalkaskian, Kalkaska

- Leelanau Enterprise, Leland

- Ludington Daily News

- Manistee Daily News Advocate

- Mears News, historical/defunct

- Midland Daily News

- Missaukee Sentinel (Lake City)

- Northern Express Weekly, weekly in Traverse City

- Onaway Outlook

- Oscoda Press

- Petoskey News-Review

- Presque Isle County Advance, Rogers City

- St. Ignace News, serving the Straits area

- The Town Meeting, Elk Rapids

- Traverse City Record-Eagle

- White Pine Press,[194] Northwestern Michigan College

Daily editions of the Detroit Free Press and The Detroit News are also available throughout the area with the Bay City Times and Saginaw News available in the east and The Grand Rapids Press available in the west.

Magazines

- Traverse is published monthly with a focus on regional interests.

Radio

FM

// designates a simulcast.

- 88.5 WIAB Mackinaw City – //88.7 WIAA

- 88.5 WSFP Rust Twp/Alpena – Smile FM

- 88.7 WIAA Interlochen – Classical "IPR Music Radio"

- 89.3 WTLI Bear Creek Twp. (Petoskey) – Contemporary Christian; Smile FM (//88.1 WLGH Lansing)

- 89.7 WJOJ Harrisville/Alpena – Smile FM

- 89.9 WLJN Traverse City – Religious

- 90.5 WPHN Gaylord – Adult Contemporary Christian "The Promise FM"; also airs on 99.7 FM translator in Petoskey

- 90.7 WNMC Traverse City – Variety, College

- 90.9 WTCK Charlevoix – Catholic; also airs on translators 92.1 FM Gaylord/95.3 FM Mackinaw City

- 90.9 WMSD Rose Township (Ogemaw County) – Religious

- 91.1 WOLW Cadillac – //90.5 WPHN

- 91.3 WJOG Good Hart/Petoskey – Smile FM

- 91.3 WZHN East Tawas – //90.5 WPHN

- 91.5 WICA Traverse City – NPR, Public News/Talk

- 91.7 WCML Alpena – Public Music Variety/News/Talk "CMU Public Radio"

- 92.1 WTWS Houghton Lake – Hot Country "92-1 The Twister"

- 92.3 WBNZ Beulah – currently silent

- 92.5 WFDX Atlanta – Silent

- 92.9 WJZQ Cadillac/Traverse City – Contemporary Hits "Z-93"

- 93.5 WBCM Boyne City – //103.5 WTCM

- 93.7 WKAD Harrietta/Cadillac – Oldies "Oldies 93.7"

- 93.9 WAVC Mio – //Talk radio "The Patriot"

- 94.3 WCMV-FM Leland/Traverse City – Silent

- 94.5 WSBX Mackinaw City – Classic Rock "94.5 WSBX"

- 94.9 WKJZ Hillman/Alpena – //103.3 WQLB; also airs on 98.1 FM translator in Alpena proper

- 95.5 WGFE Glen Arbor – Modern Rock "The Zone"

- 95.7 WCMB-FM Oscoda – CMU Public Radio

- 96.1 WHNN Bay City – Classic Hits; listenable in the West Branch and Tawas areas

- 96.3 WLXT Petoskey – Adult Contemporary "Lite 96"

- 96.7 WLXV Cadillac – Hot Adult Contemporary "Mix 96"

- 96.7 WRGZ Rogers City – //99.3 WATZ

- 96.9 WWCM Standish – CMU Public Radio

- 97.3 WDEE-FM Reed City/Big Rapids – Oldies "Sunny 97.3"

- 97.5 WKLT Kalkaska/Traverse City – Classic Rock "KLT the Rock Station"

- 97.7 WMLQ Manistee – Soft Adult Contemporary/EZ Listening "97 Coast-FM"

- 97.7 WMRX-FM Beaverton – Oldies/Adult Standards "Timeless Favourites"

- 98.1 WGFN Glen Arbor/Traverse City – Classic Rock "The Bear"

- 98.5 WUPS Harrison/Mount Pleasant – Classic Hits "98.5 UPS"

- 98.9 WKLZ Petoskey – //WKLT 97.5

- 99.3 WATZ Alpena – Country

- 99.3 WLLS Beulah – Silent

- 99.9 WHAK-FM Rogers City – Oldies "99-9 The Wave"

- 100.3 WGRY Grayling – Country "Y100"

- 100.7 WWTH Oscoda – Country "Thunder Country" also airs on 94.1 FM translator in Alpena

- 100.9 WICV East Jordan/Charlevoix – //88.7 WIAA

- 101.1 WQON Roscommon/Grayling – Adult Contemporary "Decades 101"

- 101.5 WMJZ Gaylord – Adult Hits "Eagle 101.5"

- 101.5 WMTE Manistee – Classic Hits "Kool 101.5"

- 101.9 WLDR Traverse City – Country "Sunny Country"

- 102.1 WLEW Bad Axe – Adult Hits; listenable on the Lake Huron west shore up to Harrisville.

- 102.7 WMOM Ludington/Pentwater – Top 40 "Always Listen to your Mom"

- 102.9 WMKC St. Ignace – Country "102.9 Big Country Hits"

- 103.3 WQLB Tawas City – Classic Hits "Hits FM"

- 103.5 WTCM-FM Traverse City – Country "Today's Country Music"

- 103.9 WCMW Harbor Springs – CMU Public Radio

- 104.3 WRDS-LP Roscommon – Southern Gospel "The Lighthouse"

- 104.7 WKJC Tawas City – Country

- 104.9 WAIR Lake City/Cadillac – Smile FM

- 105.1 WGFM Cheboygan – //98.1 WGFN

- 105.5 WSJR Honor/Traverse City – //106.7 WSRT

- 105.5 WBMI West Branch – Classic Country

- 105.7 WZTK Alpena – news, talk and sports

- 105.9 WKHQ Charlevoix – Contemporary Hits "106 KHQ"

- 106.1 WTZM Tawas City – //90.5 WPHN

- 106.3 WWMN Ludington – Hot Adult Contemporary "The Lakeshore's Hit Music Station"

- 106.7 WSRT Gaylord – Adult Contemporary "106.7 You FM" also airs on 95.3 FM translator in Petoskey area

- 107.1 WCKC Cadillac – //98.1 WGFN

- 107.5 WCCW Traverse City – Oldies "Oldies 107.5"

- 107.7 WHSB Alpena – Hot Adult Contemporary "107-7 The Bay"

- 107.9 WCZW Charlevoix/Petoskey – //107.5 WCCW

AM

- WTCM 580 50000 watt day, 1100 night, directional day and night, Talk, Traverse City

- WARD 750 1000 watt day, 330 night, directional day and night, Country (with WLDR-FM 101.9), Petoskey

- WMMI 830 1000 day only, talk, Shepherd

- WIDG 940 5000 watt day, 4 watt night, Catholic Talk, St. Ignace

- WHAK 960 5000 watt day, 137 night, Country (simulcasting WWTH FM Oscoda), Rogers City – simulcast of WWTH 100.7 FM

- WJML 1110 10000 watt day, 10 night, directional day and night, Talk, Petoskey

- WJNL 1210 50000 watt day, 2500 critical hours, day only, Talk (with WJML-AM), Kingsley

- WMQU 1230 1000 watt day and night, Adult Standards, Grayling

- WATT 1240 1000 watt day and night, Talk, Cadillac

- WCBY 1240 1000 watt day and night, Classic Country "Big Country Gold"

- WMKT 1270 27000 watt day, 5000 night, directional night, Talk, Charlevoix

- WMBN 1340 1000 watt day and night, Adult Standards, Petoskey

- WLJW 1370 5000 watt day, 1000 night, directional day and night, Christian Talk, Cadillac

- WLJN 1400 1000 watt day and night, Christian, Traverse City

- WIOS 1480 1000 watt day only, directional, Adult Standards, Tawas City "The Bay's Best"

Broadcast television

The following stations serve parts of Northern Michigan as their viewing area, and also some areas outside of the region.

Transportation

Transportation by air

Airports serving Northern Michigan include MBS International Airport near Freeland, Pellston Regional Airport,[195] Traverse City Cherry Capital Airport and Alpena County Regional Airport in the Lower peninsula. Depending on one's destination, Chippewa County International Airport in Sault Ste. Marie, in the eastern Upper peninsula might be a viable alternative. Grand Rapids and Bishop airport at Flint (although neither is within the area) also have scheduled service proximate to parts of the region. The Oscoda-Wurtsmith Airport is now a public airport which gives 24-hour near-all-weather service for general aviation.

Transportation by water

Several ferries still operate in the region.

- The SS Badger carferry departs from Ludington and arrives in Wisconsin.

- Ferry service between Charlevoix and Beaver Island is provided by M/V Emerald Isle, and occasionally, the older M/V Beaver Islander.[196]

- The Straits of Mackinac is home to lake ferries that take passengers to Mackinac Island from either Mackinaw City in the Lower Peninsula or St. Ignace in the Upper Peninsula.

- A ferry for tours of Charity Island in the middle of Saginaw Bay and the Charity Island Light (and even dinner cruises) are available. It leaves from Au Gres on the mainland, south of Tawas.[197]

- The Kristen D is a ferry which operates between Cheboygan and Bois Blanc Island.[198]

The largest bridge in Northern Michigan is the Mackinac Bridge connecting Northern Michigan to the Upper Peninsula. The second largest is the Zilwaukee Bridge.

Transportation by land

On land, Michigan is a unique travel environment. Consequently, drivers should be forewarned: travel distances should not be underestimated. Michigan's overall length is only 456 miles (734 km) and width 386 miles (621 km) – but because of the lakes those distances cannot be traveled directly. The distance from northwest to the southeast corner is 456 miles (734 km) "as the crow flies". However, travelers must go around the Great Lakes. For example, when traveling to the Upper Peninsula, it is well to realize that it is roughly 300 miles (480 km) from Detroit to the Mackinac Bridge, but it is another 300 miles (480 km) from St. Ignace to Ironwood.

Likewise direct routes are few and far between Interstate 75 (I-75) and M-115 do angle from the southeast to the northwest), but most roads are oriented either east–west or north–south (oriented with township lines set up under the Land Ordinance of 1785).

Transit

Automobile roads

The primary means of transportation in Northern Michigan is by automobile. Northern Michigan is served by one Interstate, and a number of U.S. Highways and Michigan state trunklines.[199]

I-75 runs northwest–southeast through the region between the Flint/Tri-Cities area and Mackinac Bridge at Mackinaw City, which leads on to the Upper Peninsula.

I-75 runs northwest–southeast through the region between the Flint/Tri-Cities area and Mackinac Bridge at Mackinaw City, which leads on to the Upper Peninsula. US 10 enters Michigan after it crosses Lake Michigan from Manitowoc to Ludington. US 10 runs from Ludington through Baldwin and Reed City before it becomes a freeway west of US 127 near the junction with M-115. US 10 bypasses Midland and terminates at I-75 in Bay City.

US 10 enters Michigan after it crosses Lake Michigan from Manitowoc to Ludington. US 10 runs from Ludington through Baldwin and Reed City before it becomes a freeway west of US 127 near the junction with M-115. US 10 bypasses Midland and terminates at I-75 in Bay City. US 23 runs northward for about 200 miles (320 km) along (or parallel with) the Lake Huron shoreline as the Sunrise Side Coastal Highway from the Flint/Tri-Cities area.

US 23 runs northward for about 200 miles (320 km) along (or parallel with) the Lake Huron shoreline as the Sunrise Side Coastal Highway from the Flint/Tri-Cities area. US 31 mainly parallels the Lake Michigan shore from the Ludington area north to Mackinaw City; near Traverse City, the highway cuts the base of the Leelanau Peninsula.

US 31 mainly parallels the Lake Michigan shore from the Ludington area north to Mackinaw City; near Traverse City, the highway cuts the base of the Leelanau Peninsula. US 127 ends at Grayling, connecting Northern Michigan with points south

US 127 ends at Grayling, connecting Northern Michigan with points south US 131 is a primary north–south highway that is a freeway from Manton southwards; north of the freeway terminus, the highway is mostly two lanes, connecting Kalkaska, Mancelona, and ending at US 31 in Petoskey.