Nyau (also: Nyao meaning mask[1] or initiation) is a secret society of the Chewa, an ethnic group of the Bantu peoples from Central and Southern Africa.[2] The Nyau society consists of initiated members of the Chewa people, forming the cosmology or indigenous religion of the people. Initiations are separate for men and for women, with different knowledge learned and with different ritual roles in the society according to gender and seniority. Only initiates are considered to be mature and members of the Nyau.[3][4]

The word Nyau is not only used for the society itself, but also for the indigenous religious beliefs or cosmology of people who form this society, the ritual dance performances, and the masks used for the dances. Nyau societies operate at the village level, but are part of a wide network of Nyau across the central and part of the southern regions of Malawi, eastern Zambia, western Mozambique and areas where Malawians migrated in Zimbabwe.[3][4]

During performances with the masks women and children often rush into the houses when a Nyau performer threatens, as the masks are worn by only male members of the society and represent male knowledge. At that moment in the performance and rituals, Nyau masked dancers are understood to be spirits of the dead. As spirits the masquerades may act with impunity and there have been attacks and deaths during performances in the past.[3][4] Increasing westernization has led to a decrease in Nyau.

History

A cave painting in Zaire depicts Kasiya Maliro, a type of Nyau mask that may date to 992 CE.[5] The Nyau cosmology continued during the time of the Ngoni invasions in the mid-1800s and during the time of early colonists including Portuguese and British. According to local mythologies Nyau came from Malomba, a place in what is now the DRC.[6] Due to heavy punishment for telling secrets to non-initiates about the Nyau cosmology (e.g. who are the men dancing) the origin of Nyau could not be clarified by the first missionaries and colonialists arriving in Maravi.[7] Penalties went as far as the person revealing secrets being killed by members of the society.[2]

The arrival of missionaries during the 1920s had a growing influence on Nyau at the village level, which produced open conflict.[3] Though Christian missionaries banned Nyau in Chewa communities, the society and its practice survived under British colonial rule through adaptation that included some aspects of Christianity. Presently, it is still practiced with Chewa members belonging both to a Christian church and the Nyau society.[8] Although some other ethnic groups have developed cultural dances, such as the Ngoni, Yao and Mang'anja,[9] the Nyau of the Chewa can be considered the most elaborate of the secret societies and dances in areas around Lake Malawi.[10]

Belief system

The Chewa believe that life exists within their ancestors and those not yet born, as well as the living.[11] The Nyau beliefs include communication with those who are dead, or their spirits, calling this act pemphero lalikulu ("Great Prayer").[8] Chewa believe in the presence of God in everyday life, and that God is both male (in the sky) and female (in the earth). Words for God include Chiuta, the great bow or rainbow in the sky and Namalango in the earth, like a womb, where seeds germinate and is a source of new life.[12]

The spirit world's symbolism is presented at the Gule Wamkulu ("Big Dance"), which incorporates mwambo ("traditions"), masks, song, dance and rules. Nyau incorporates sophisticated reverse role-playing, proverbs, mimicking and satire in performances. Primarily the Nyau perform their masked dances at funerals, memorial services and initiations (for girls: Chinamwali).[6][13][14][15]

Each dancer represents a special character relating to the mask or animal structure he wears. The zilombo ("wild animals") are large constructions that cover the entire body and mostly represent animals, and the masks worn over the face are primarily ancestral spirits. The secrecy behind Nyau incorporates coded language, riddles, metaphor, myths and signing. Viewed with suspicion by outsiders, Nyau has been misunderstood and misrepresented by others, including the Christian church.[6][13]

Initiation of men into the secret society begins with residing in a wooded grove, the place the dead are buried (cemetery) for a week or much longer in the past. Particularly in Zimbabwe, Nyau members that migrated from Malawi and are now part of the Shona Culture still practice Nyau rituals and hold Nyau religious beliefs. They perform dances in the suburbs of Mabvuku, Highfield and Tafara. They attempt to scare away people who wish to interview them saying "Wavekutamba nemoto unotsva" (you are now playing with fire you will get burnt).[16]

Women and children and also some men may rush into the houses when a Nyau performer appears. Nyau is the presence of the dead, an encounter with a spirit and so associated with fear and ritual dread. However, senior women perform in the Gule Wamkulu with intricate clapping, singing, dancing and chanting, responding to the song of the masquerader and are close to the dancers. During the funeral period, women joke with the Nyau in a practice called kasinja whilst brewing beer and while staying awake the night before a funeral. Men and women both enter the graveyard grove burials at the end of the Nyau funeral performance. Initiated women attend the Nyau performances freely, though they will deny knowledge of the men wearing masks.[3][6]

The men are actual spirits in the ritual, and cannot be spoken of as men even though women will recognize their husbands, fathers, brother and uncles. Identifying the man wearing a mask is disrespectful to the religion, breaking the moment when the masquerade is the spirit of the dead, much as calling Eucharist a biscuit breaks the ritual moment when Christ is near and would be considered disrespectful to Christians. Uninitiated women and children, and uninitiated men, may be chased by Nyau performers and non-members are discouraged from coming near during funerals. In part this is to avoid outsiders from being disrespectful, not understanding the importance of a 'good' burial and the significance of the presence of the dead.[3][6]

In Zambian villages, boys may participate in groups called kalumbu who join a group from as young as five or six.[3] They must pay a joining fee (often around 2 kwacha in 1993) which they raise by hunting and selling birds, or the fee is paid by their parents.[3] Upon joining the novices are often beaten with branches before learning the discipline.[3] The minimum age of boys or girls joining the Nyau itself is usually around ten years of age.[6][17]

Dances

Nyau dances involve intricate footwork, flinging dust in the air. Dancers respond to specific drumbeats and songs depending on the mask type or character. The dancers, described as "fleet-footed or nimble-footed", appear in masks representing the dead, human being or animal; the weak-kneed run away from sights of such dances.[16] While it may be considered in many places to be a folk dance, this is certainly not the case; Nyau should rather be considered a religious dance, as its function is to communicate with the ancestral world.

Since 2005, Gule Wamkulu has been classified as one of the 90 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity, a program by UNESCO for preservation of intangible cultural heritage. This dance form may date to the great Chewa Empire of the 17th century.[18] Gule Wamkulu, or big dance, is the best-known and longest dance of the Nyau. It is also known as pemphero lathu lalikulu la mizimu ("great prayer to our ancestors") or gulu la anamwaliri ("dance of the ancestors"). Prior to the Gule Wamkulu dance, Nyau dancers observe a series of secret rituals which are associated with their society, a secret brotherhood.[19]

The dance is mainly performed at funerals and memorial services but also at initiations and other celebrations. The masks worn by the dancers on such performances are in the form of animals or "beasts" such as antelopes believed to capture the soul or spirit of the deceased that brings renewed life. The purpose of the dance is said to be a way of communicating messages of the ancestors to the villagers and making possible continued harvests and continued life. Nyau is a protection against evil and an expression of religious beliefs that permeate society.[6][20]

Attire

The variety of masks resembling ancestors is huge and ever growing, unlike the animal structures. Some mask carvers are professionals while others are occasional artisans.[18] Over 400 masks which are associated with the Nyau society and the Gule wamkulu ritual are exhibited at the Chamare Museum in Dedza District, Malawi.[5]

Masks

.jpg.webp)

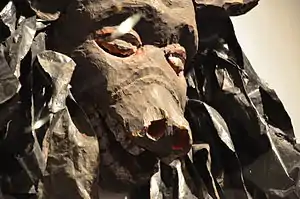

Nyau masks are constructed of wood and straw. and are divided into three types.[21] The first is a feathered net mask, the second is a wooden mask and the third is a large zoomorphic basketry structure that envelops the entire body of the dancer.[6][21] Wearing the latter, dancers tend to turn around and around in a motion known as Nyau yolemba.[21] They are representations of a large variety of characters, including wild animals such as antelope, lions and hyenas.[4]

With names such as Bwindi, Chibano, and Wakana, the masks portray a variety of traits and types such as a philanderer, a helpless epileptic, lust, greed, foolishness, vanity, infertility, sorcery, and ambition.;[13] even a helicopter.[18] As one Nyau member explains, the masks and performance represent all of humanity and all of the spirit world.[6]

There are a variety of mask types, some of which include:[2]

- Bwana wokwera pa ndege/pa galimoto (Mister in a plane/in a car) This mask shows how those who already had money and power in their lifetime will keep this even when they have passed in the ancestral world.

- Chabwera kumanda (the one who came back from the grave) is a character who misreads people and resembles an ancestor who hunts people in their dreams in order to get attention and offerings (e.g. beer, meat, etc.). His dance Chabwera kumanda chases people around which underlines his evil character.

- Kasinja or Kamchacha is the messenger of important ancestors. He sometimes partly plays some kind of moderator and tells which mask or animal is coming next to perform its dance.

- Kondola which originated as Msakambewa ("Mouse Hunter"), then changed into To Ndola (a man in a copper mining town), and then changed again, to Chizonono (someone afflicted with gonorrhea), is an example of a mask that has undergone transformation because of changing pressures and societal influences.

- Maliya (from Mary) represents a kind-hearted female ancestor. This dancer will sing and dance together with the people.

- Mfiti (male witch) wears a very nasty mask and has in general a very demolished and shaggy appearance. The outer shape resembles its evil character, since witches are believed to kill people with their juju.

- Simoni (from Saint Peter) wears a red mask, resembling an Englishman with sunburn; he also wears a suit made of rags. This character might be a caricature of an English colonialist.

Animal structures

The Nyau members wearing animal structures resemble wild animals or nyama za ku tchire, which appear at the time of death of people and therefore feared. There is some kind of hierarchy between the different animals, with some very respected animals (such as njobvu, the elephant) and some less important. Highly respected animals are also believed to resemble very important ancestors such as chiefs or members of the Nyau cult. Most animal structures usually have a barrel-like shape, with an entry hole at the bottom. Inside the structure, bars are mounted to be able to carry the structure around. All structures completely cover the dancer, and the footprints are brushed away with branches by Nyau members.[6] In the following some structures are explained in order of their importance.[2]

- Njobvu (the elephant) is the most important figure of all. Four Nyau dancers are needed to move this structure. Njobvu resembles an important chief, since the elephant is the most important animal for the Chewa, because of its size. Therefore, this rare structure is only seen at funerals for chiefs.

- Ndondo (the snake) is the second-most important structure and is carried around by up to twelve men. It also resembles an important ancestor and is often seen at funerals for members of the Nyau.

- Mkango (the lion) resembles the evil spirit of an ancestor, which attacks and even kills people. Therefore, some people run away as soon as they see Mkango approaching. The figure Mkango illustrates that ancestors must not be annoyed, just as a lion must not be annoyed, since it might attack people for their disrespect.

The antelope forms are considered the most beautiful and are widely known as Kasiyamaliro (to leave the funeral/burial behind). Standing ten feet tall and often covered in dried woven maize husks, these mask forms are the first to appear in performances to remember the deceased, as a sign that the deceased have now joined the spirits and ancestors. This is a time of remembrance and celebration of life.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ D.D.Phiri: History of Malawi - From the earliest times to the year 1915. in: CLAIM, pp.31 (2004)

- 1 2 3 4 Van Breugel, J. W. M. (2001). Chewa Traditional Religion. Christian Literature Association in Malawi. pp. 125–168. ISBN 978-99908-16-34-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Linden, Ian; Linden, Jane (1 January 1974). Catholics, peasants, and Chewa resistance in Nyasaland, 1889–1939. University of California Press. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-0-520-02500-4. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Ottenberg, Simon; Binkley, David Aaron (2006). Playful performers: African children's masquerades. Transaction Publishers. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-7658-0286-6. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- 1 2 Bell, Deborah (10 September 2010). Mask Makers and Their Craft: An Illustrated Worldwide Study. McFarland. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-0-7864-4399-4. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Birch de Aguilar, Laurel (1996). Inscribing the Mask: Nyau Ritual and Performance among the Chewa of central Malawi. Anthropos Institute, Sankt Augustin Germany and University of Freiburg Press.

- ↑ R.S. Rattray: Some Folk-Lore Stories and Songs in Chinyanja, London: Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (1907), pp. 178–79.

- 1 2 "Gule Wamkulu". Embassy of Malawi. 2007. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ↑ J.M. Schofeleers: Symbolic and Social Aspects of Spirits Worship among the Mang'anja, Ph.D. Dissertation (1968) Oxford, pp. 307–415.

- ↑ Hodgson, AGO (Jan–Jun 1933). "Notes on the Achewa and Angoni of the Dowa District of the Nyasaland Protectorate". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 63: 146. JSTOR 2843914.

- ↑ Sitshwele, Miliswa (June 21, 2010). "The Elephant has Four Hearts: Nyau Masks and Rituals :a book review". The Origins Centre is an initiative of the University of the Witwatersrand. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ↑ Laurel Birch de Aguilar, Inscribing the Mask 1996

- 1 2 3 Curran, Douglas (Autumn 1999). "Nyau Masks and Ritual". African Arts. 68 (3): 68–77. JSTOR 3337711.

- ↑ Zubieta, Leslie F. (2006). The rock art of Mwana wa Chentcherere II rock shelter, Malawi : a site-specific study of girls' initiation rock art. African Studies Centre, Leiden.

- ↑ Zubieta, Leslie F. (2016). "Animals' Role in Proper Behaviour: Cheŵa Women's Instructions in South-Central Africa". Conservation & Society. 14 (4): 406–415.

- 1 2 "Zimbabwe: Demystifying Intrigue of Nyau Culture". The Herald of the Government of Zimbabwe. 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2011.

- ↑ Morris, Brian (14 September 2000). Animals and ancestors: an ethnography. Berg. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-1-85973-491-9. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Gule Wamkulu". UNESCO. 2005. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ↑ Kalusa, Walima T.; Mtonga, Mapopa (2 January 2010). Kalonga Gawa Undi X: a biography of an African chief and nationalist. African Books Collective. pp. 104–. ISBN 978-9982-9972-5-6. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- ↑ Breugel, J. W. M. van; Ott, Martin (2001). Chewa traditional religion. Christian Literature Association in Malawi. p. 167. ISBN 978-99908-16-34-1. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 Harding, Frances (2002). The performance arts in Africa: a reader. Routledge. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-415-26198-2. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

Literature

- Boucher (Chisale), Claude When Animals Sing and Spirits Dance: Gule Wamkulu: the Great Dance of the Chewa People of Malawi. Kungoni Centre of Culture and Art, 2012

- Gerhard Kubik: Makisi nyau mapiko. Maskentradition im bantu-sprachigen Afrika. Trickster Verlag, München 1993

- W.H.J. Rangeley: Nyau in Kotakota District. The Nyasaland Journal No.2, 1949

- Laurel Birch de Aguilar Inscribing the Mask: Nyau Ritual and Performance among the Chewa of central Malawi, Anthropos Institute and University of Freiburg Press, 1996