| Oopsacas minuta | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Porifera |

| Class: | Hexactinellida |

| Order: | Lyssacinosida |

| Family: | Leucopsacidae |

| Genus: | Oopsacas |

| Species: | O. minuta |

| Binomial name | |

| Oopsacas minuta Topsent, 1927 | |

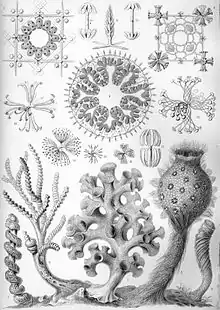

Oopsacas minuta is a glass sponge that is a member of the Hexactinellida. Oopsacas minuta is found in submarine caves in the Mediterranean. It is reproductive year-round. This species is a part of a class that are usually bathyal and abyssal.[1] Meaning they grow at a depth over 200 meters. At this depth the temperature is low and constant, so silica metabolism is optimized. However, this species has been observed in shallow water.[1] O. minuta have only been observed by exploring caves that trap cold water. The shape of the sponge is elongated, cylindrical and a little flared. It is between a few millimeters and 3.5 centimeters. O. minuta are white are held up with a siliceous skeleton. The spicules of the skeleton intersect in an intricate network.[2] These spindles partially block the top of the sponge. There are no obvious oscules. The sponge is anchored or suspended from the cave by silica fibers. This class of sponge is different from the three other classes of Porifera. It differs in tissue organization, ecology, development and physiology. O. minuta belongs to the order Lyssacinosida. Lyssacinosida are characterized by the parenchymal spicules mostly being unconnected; this is unlike other sponges in the subclass where the spicules form a connected skeleton.[3] The genome of O. minuta are one of the smallest of all the animal genomes that have been sequenced so far.[4] Its genome contains 24 noncoding genes and 14 protein-encoding genes.[5] The spindles of O. minuta have three axes and six points. This species does not have pinacocytes, which are the cells that form the outer layer in other sponges.[6] Instead of true choanocytes it has frill structures that bud from the syncytium.

Feeding

The Oopsacas minuta is a filter feeder. It sucks in water and eats microphage. The internal flagellum beat and create a stream of water filled with bacteria and food particles; it is retained in frills that come from a syncytium.[7] This multinucleated syncytium is the major tissue component of Hexactinellid sponges.[8] Glass sponge reefs are known for having the highest grazing rate of any benthic suspension feeding community.[9]

Reproduction

Oopsacas minuta is a viviparous species, meaning they produce living young instead of eggs. The mother sponge will release a small ciliated larva. This larva leads a short pelagic life in the open water inside the cave. It then settles on the bedrock of the cave. Embryonic development of the O. minuta goes through the classic cell divisions, some of the cells fuse and the syncytium is formed secondary. Something that is unique in the Porifera phylum is that the first stages of cleavage are spiral, and gastrulation happens by primary delamination.[10] O. minuta reproduce year-round and produces the only known live larvae.[11] Asexual reproduction has not been observed from this species.

Embryogenesis

Glass sponges (Hexactinellids) have different body plans than other members of the Metazoan because the adult tissue is made up of a single giant multinucleated syncytium. This multinucleated syncytium creates the inner and outer layers of the sponge and is connected to uninucleate cellular regions by cytoplasmic bridges.[7] In O. minuta differentiation of the tissues happens early in embryogenesis. All cells and syncytia are linked together by cytoplasmic bridges.[7]

Metamorphosis

A study done using three-dimensional models showed the larval tissue reorganization at metamorphosis of the larva. The larvae land on their anterior swimming pole or on one side. During the first stage of metamorphosis the multiciliate cells form a belt around the larva and then are discarded. Throughout metamorphosis the larval flagellated chambers are maintained. These larval flagellated chambers become the kernels of the first pumping chambers of the juvenile sponge.[12] Once the larvae of the O. minuta settle syncytial tissues containing yolk inclusions enlarge the larval chambers. Lipid inclusions that are located at the basal attachment site, become smaller. The post-metamorphic flagellated chambers are formed from flagellated chambers.[12]

References

- 1 2 Bakran-Petricioli, Tatjana; Vacelet, Jean; Zibrowius, Helmut; Petricioli, Donat; Chevaldonné, Pierre; Raa, Tonći (10 September 2007). "New data on the distribution of the 'deep-sea' sponges Asbestopluma hypogea and Oopsacas minuta in the Mediterranean Sea: New distribution data on Mediterranean 'deep-sea' sponges". Marine Ecology. 28: 10–23. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0485.2007.00179.x.

- ↑ US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "What is a glass sponge?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ↑ "Lyssacinosida". 18 April 2023.

- ↑ Santini, Sébastien; Schenkelaars, Quentin; Jourda, Cyril; Duschene, Marc; Belahbib, Hassiba; Rocher, Caroline; Selva, Marjorie; Riesgo, Ana; Vervoort, Michel; Leys, Sally P.; Kodjabachian, Laurent; Bivic, André Le; Borchiellini, Carole; Claverie, Jean-Michel; Renard, Emmanuelle (27 July 2022). "The compact genome of the sponge Oopsacas minuta (Hexactinellida) is lacking key metazoan core genes": 2022.07.26.501511. doi:10.1101/2022.07.26.501511.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Jourda, Cyril; Santini, Sébastien; Rocher, Caroline; Le Bivic, André; Claverie, Jean-Michel (30 July 2015). "Mitochondrial Genome Sequence of the Glass Sponge Oopsacas minuta". Genome Announcements. 3 (4): e00823–15. doi:10.1128/genomeA.00823-15. ISSN 2169-8287. PMC 4520895. PMID 26227597.

- ↑ "28.1B: Morphology of Sponges". Biology LibreTexts. 16 July 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- 1 2 3 Leys, S (1 April 2006). "Embryogenesis in the glass sponge Oopsacas minuta: Formation of syncytia by fusion of blastomeres". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 46 (2): 104–117. doi:10.1093/icb/icj016. PMID 21672727. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ↑ Leys, Sally (1 February 2003). "The Significance of Syncytial Tissues for the Position of the Hexactinellida in the Metazoa". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 43 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1093/icb/43.1.19. PMID 21680406. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ↑ Kahn, Amanda S. (Fall 2016). "Ecophysiology of glass sponge reefs". ERA. doi:10.7939/R3FX74C5V. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ↑ Boury-Esnault, N.; Efremova, S.; Bézac, C.; Vacelet, J. (1999). "Reproduction of a hexactinellid sponge: first description of gastrulation by cellular delamination in the Porifera". Invertebrate Reproduction & Development. 35 (3): 187–201. doi:10.1080/07924259.1999.9652385. S2CID 85088957.

- ↑ Sadler, Pamela (16 December 2020). "Spicules - Reproductive Biology". GUWS Medical. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- 1 2 Leys, Sally P.; Zaman, Afyqah Kamarul; Boury-Esnault, Nicole (2016). "Three-dimensional fate mapping of larval tissues through metamorphosis in the glass sponge Oopsacas minuta". Invertebrate Biology. 135 (3): 259–272. doi:10.1111/ivb.12142. ISSN 1077-8306. JSTOR 45154758.