Opole | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp)

| |

Coat of arms | |

Opole  Opole  Opole | |

| Coordinates: 50°40′N 17°56′E / 50.667°N 17.933°E | |

| Country | Poland |

| Voivodeship | Opole |

| County | city county |

| Established | 8th century |

| Town rights | 1217 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Arkadiusz Wiśniewski |

| Area | |

| • City | 148.9 km2 (57.5 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 338.4 km2 (130.7 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 176 m (577 ft) |

| Population (31 03 2021 census) | |

| • City | 127,387[1] |

| • Density | 856/km2 (2,220/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 146,522 |

| • Metro density | 433/km2 (1,120/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 45-001 to 45-960 |

| Area code | +48 077 |

| Car plates | OP |

| Website | https://www.opole.pl |

Opole (Polish: [ɔˈpɔlɛ] ⓘ; German: Oppeln [ˈɔpl̩n] ⓘ; Silesian: Ôpole)[lower-alpha 1] is a city located in southern Poland on the Oder River and the historical capital of Upper Silesia. With a population of approximately 127,387 as of the 2021 census,[1] it is the capital of Opole Voivodeship (province) and the seat of Opole County. Its built-up (or metro area) was home to 146,522 inhabitants. It is the largest city in its province.

Its history dates to the 8th century, and Opole is one of the oldest cities in Poland. An important stronghold in Poland, it became a capital of a duchy within medieval Poland in 1172, and in 1217 it was granted city rights by Duke Casimir I of Opole,[6] the great-grandson of Polish Duke Bolesław III Wrymouth. During the Medieval Period and the Renaissance, the city was known as a centre of commerce; several main trade routes intersected here, which helped to generate steady profits from transit trade. The rapid development of the town was also caused by the establishment of a seat of regency in Opole in 1816. The first railway connection between Opole, Brzeg and Wrocław was opened in 1843 and the first manufacturing plants were constructed in 1859, which greatly contributed to the city's regional significance.[7]

The city's extensive heritage entails several cultures of Central Europe, as it was under periods of Polish, Bohemian (Czech), Prussian, and German rule. Opole formally became part of Poland again in 1945 after the end of World War II. Many German Upper Silesians and Poles of ethnic German ancestry still reside in the Opole region; but, following the 1945–46 expulsions, in the city of the 21st century, ethnic Germans make up less than 3% of the population.

There are four higher education establishments in the city: the Opole University, Opole University of Technology, a Medical College and the private Higher College of Management and Administration. The National Festival of Polish Song has been held here annually since 1963. Each year new regular events, fairs, shows and competitions take place.[8]

Opole is sometimes referred to as "Polish Venice",[9] because of its picturesque Old Town and several canals and bridges connecting parts of the city.

Names and etymology

The name Opole likely originated from the medieval Slavic term for a group of settlements.[10]

Names for the city in other relevant languages include Lower Silesian: Uppeln, Czech: Opolí, Latin: Oppelia, Oppolia or Opulia.

History

In Medieval Poland

Opole's history begins in the 8th century. At this time, according to the archeological excavations,[11] the first settlement was founded on the Ostrówek – the northern part of the Pasieka Island in the middle of the Oder river. In the early 10th century it developed into one of the main "gords" of the Lechitic (Polish) Opolans tribe.

At the end of the century Silesia became part of Poland and was ruled by the Piast dynasty; the land of the pagan Opolanie was conquered by Duke Mieszko I in 992. From the 11th–12th centuries it was also a castellany. After the death of Duke Władysław II the Exile, Silesia was divided in 1163 between two Piast lines – the Wrocław line in Lower Silesia and the Opole-Racibórz of Upper Silesia. Opole would become a duchy in 1172 and would share much in common with the Duchy of Racibórz, with which it was often combined. In 1281 Upper Silesia was divided further between the heirs of the dukes. The Duchy of Opole was temporarily reestablished in 1290.

In the early 13th century, Duke Casimir I of Opole decided to move the settlement from the Pasieka Island to the right shore of the Oder river (since the 17th century, the old stream bed of the Oder, known as the Młynówka). All of the inhabitants had to be moved in order to accommodate the castle that was built in place of the old city.[12] Former inhabitants of Ostrówek, together with German merchants that immigrated from the West, received the first town rights probably as early as around 1217, although this date is disputed.[13] Opole received German town law in 1254, which was expanded with Neumarkt law in 1327. Opole developed during the rule of duke Bolko I of Opole. The castle was finally completed around this time and new buildings, including the city walls and the Holy Cross Church, were constructed.

Along with most of Silesia, in 1327 the Duchy of Opole came under the sovereignty of the Kingdom of Bohemia, itself part of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1521 the Duchy of Opole inherited the Duchy of Racibórz (Ratibor), by then also known by its German equivalent – Oppeln. The second castle of Opole was probably founded in the 14th century by duke Vladislaus II, though some sources claim that it was originally a wooden stronghold of Opole's castellan dating into 12th century.[14]

Austrian Habsburgs and Polish Vasas rule

With the death of King Ludvík II of Bohemia at the Battle of Mohács, Silesia was inherited by Ferdinand I, placing Opole under the sovereignty of the Habsburg monarchy of Austria. The Habsburgs took control of the region in 1532 after the last Piast duke of Opole, Jan II the Good, died. At that time the city was still mainly Polish-speaking (around 63%), with other nationalities represented mainly by Germans, Czechs and Jews. The last two dukes of Opole, Nicholas II and Janusz II the Good, did not master the German language.[15]

Beginning in 1532 the Habsburgs pawned the duchy to different rulers including several monarchs of Poland (see Dukes of Opole). After the Swedish invasion of Poland, in 1655 the King of Poland, John II Casimir Vasa, stayed with his entire court in Opole. In Opole in November 1655, the Universal of Opole (Uniwersał opolski) was issued by the King, calling for Poles to rise against the Swedes, who at that time occupied a large part of Poland.

With the abdication of King John II Casimir of Poland as the last Duke of Opole in 1668, the region passed to the direct control of the Habsburgs. At the beginning of the 18th century the German population of Opole was estimated at around 20%.[16]

In Prussian Silesia

King Frederick II of Prussia conquered most of Silesia from Austria in 1740 during the Silesian Wars; Prussian control was confirmed in the Peace of Breslau in 1742. In the 18th century, Opole belonged to the tax inspection region of Prudnik.[17] Under Prussian rule the ethnic structure of the city began to change. In the early 20th century the number of Polish and bilingual citizens of Opole, according to the official German statistics, varied between 25% and 31%.[18] Nonetheless, Opole remained an important cultural, social and political center for the Poles of Upper Silesia. From 1849 the Polish newspaper Gazeta Wiejska dla Górnego Śląska was published in Opole. Polish reporter and opponent of Germanisation Bronisław Koraszewski founded the newspaper Gazeta Opolska in 1890 and the People's Bank in Opole (Opolski Bank Ludowy) in 1897.[19] Another Polish newspaper, the Nowiny was founded by Franciszek Kurpierz in 1911.

From 1816–1945 Opole was the capital of Regierungsbezirk Oppeln within Prussia. The city became part of the German Empire during the unification of Germany in 1871.

After World War I

After the defeat of Imperial Germany in World War I, a plebiscite was held on 20 March 1921 in Oppeln to determine if the city would be in the Weimar Republic or become part of the Second Polish Republic, which just regained independence. 20,816 (94.7%) votes were cast for Germany, 1,098 (5.0%) for Poland, and 70 (0.3%) votes were declared invalid. Voter participation was 95.9%. Results of the plebiscite in the Oppeln-Land county were different, with 30% of the population voting for Poland.

Oppeln was the administrative seat of the Province of Upper Silesia from 1919–1939. In the years 1928–1931, by the decision of the German regional administration, the Piast Castle was demolished. Thanks to the strong opposition of the local Polish community and protests of the Union of Poles in Germany, the castle tower was saved from demolition.[20] Nowadays called the Piast Tower it is one of the city's landmarks. In 1929, a Polish theatre from Katowice came to Opole to perform the opera Halka by Stanisław Moniuszko. After the performance, the actors were brutally beaten by a German militia with the silent consent of the German police.[21]

Local Polish activists were intensively persecuted from 1937 onwards.[22] The local Gestapo terrorized and spied on Polish activities in the German-held part of Upper Silesia, participated in espionage and sabotage in the Polish part of Silesia and prepared border provocations against Poland.[23] There was strong anti-Polish propaganda in the city and region.[23]

The local Polish newspaper Nowiny Codzienne was frequently confiscated from 1937 and its editors were harassed, its work obstructed, its distributors persecuted, and its readers threatened.[24] In 1938–1939, the local Gestapo carried out expulsions of Polish activists from the region, which the local Polish press could still report.[25] On July 2, 1939, a Nazi militia attacked and severely beat Poles going to a Polish service in the Saint Sebastian Church.[26]

World War II

_Lichen99.jpg.webp)

On August 31, the day before the German invasion of Poland that began World War II, the Germans began mass arrests of prominent Poles in the city, which were continued in September.[27] Among the arrested Poles were activists, entrepreneurs, journalists, editors, scout leaders, the director of the local Polish bank and the director of the local Polish library.[28] The Nowiny Codzienne newspaper was closed down on September 1, and its editorial team, including editor-in-chief Jan Łangowski, was deported to concentration camps.[29] In September 1939, local Polish organizations were closed down by the German police and Gestapo, and the assets of the local Polish bank were confiscated.[30] On September 13 and October 4, 1939, arrested Poles were deported from the city to concentration camps, men to Buchenwald and women to Ravensbrück.[31] Some local Poles avoided arrest by escaping earlier to Poland.[26]

The German 10th Army and 14th Army attacked Poland from the city, and the Einsatzgruppe I and II followed the armies from Opole to various Polish cities to commit crimes against the Polish people.[32] After the defeat of Poland, Polish Eastern Upper Silesia was re-annexed to the Province of Upper Silesia and Oppeln lost its status as provincial capital to German-occupied Katowice (renamed Kattowitz).

Polish prisoners from the city co-founded the secret resistance movement in Buchenwald, while Polish escapees from the city participated in the Polish resistance in occupied Poland.[33] Local members of the Polish resistance were expelled from the city.[34]

During the war, the Nazis operated thirteen forced labour subcamps of the Stalag VIII-B/344 prisoner-of-war camp for Allied POWs in the city, and two in the present-day district of Groszowice.[35]

The New Synagogue was built in 1893–1897, designed by Felix Henry. During the Kristallnacht on 9–10 November 1938 Nazis forced Rabbi Hans Hirschberg to set the building on fire.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 38,464 | — |

| 1960 | 63,500 | +65.1% |

| 1970 | 86,900 | +36.9% |

| 1980 | 116,669 | +34.3% |

| 1990 | 128,429 | +10.1% |

| 2000 | 130,427 | +1.6% |

| 2010 | 125,710 | −3.6% |

| 2020 | 127,839 | +1.7% |

| source [36] | ||

In modern Poland

After the end of the Second World War in 1945, Oppeln was transferred from Germany to Poland, pursuant to the agreements of the Potsdam Conference, and given its original Slavic name of Opole. Opole became part of the Katowice Voivodeship from 1946–1950, after which it became part of the Opole Voivodeship. Unlike other parts of the so-called Recovered Territories, Opole and the surrounding region's indigenous population partly remained and was only partly expelled as elsewhere. Over 1 million Silesians who considered themselves Poles or were treated as such by the authorities due to their language and customs were allowed to stay after they were verified as Poles in a special verification process. It involved declaring Polish nationality and an oath of allegiance to the Polish nation. Additionally, many Poles displaced from the former Polish Kresy annexed by the USSR (for example Lwów) came to Opole and the surrounding area and settled here after Second World War.[37]

In the later years however many of Germans (and German Silesians) people left to West Germany to flee the communist Eastern Bloc (see Emigration from Poland to Germany after World War II). Today Opole, along with the surrounding region, is known as a centre of the German minority in Poland that recruits mainly from the descendants of the positively verified autochthons. In the city itself however only 2.46% of the inhabitants declared German nationality according to the last national census of 2002.

On January 1, 2017, Borki, Chmielowice, Czarnowąsy, Krzanowice, Sławice, Świerkle, Winów, Wrzoski, Żerkowice as well as parts of Brzezie, Dobrzeń Mały and Karczów became a part of Opole, enlargening its population by about 9,500, and its area by over 5,300 ha, despite the protests of inhabitants.[38][39]

Historical population

In the early 20th century the number of Polish and bilingual citizens of Opole, according to the official German statistics, varied from 25 to 31%.[18]

German minority

Alongside German and Polish, many citizens of the city before 1945 used a strongly German-influenced Silesian dialect (sometimes called wasserpolnisch or wasserpolak). Because of this, the post-war Polish state administration after the annexation of Silesia in 1945 did not initiate a general expulsion of all former inhabitants of Opole, as was done in Lower Silesia, for instance, where the population almost exclusively spoke the German language. Because they were considered "autochthonous" (Polish), the Wasserpolak-speakers instead received the right to remain in their homeland after declaring themselves as Poles. Some German speakers took advantage of this decision, allowing them to remain in Opole, even when they considered themselves to be of German nationality. The city surroundings currently contain the largest German and Upper Silesian minorities in Poland. However, Opole itself is only 2.46% German.[40] (See also Germans of Poland.)

Main sights

Opole hosts the annual National Festival of Polish Song. The city is also known for its 10th-century Church of St. Adalbert and the 14th-century Church of the Holy Cross. There is a zoo, the Ogród Zoologiczny w Opolu.

Structures and buildings

- Piast Tower on the island, the only part that remained of the medieval Piast Castle, the local residence of the dukes of Opole

- Holy Trinity Church, a 14th-century Gothic Franciscan church, which contains a mausoleum of the dukes of the Opole line of the Piast dynasty

- a 19th-century Town Hall

- the Church of our Lady of Sorrows and St. Adalbert (Kościół Matki Boskiej Bolesnej i św. Wojciecha)

- the 14th-century Holy Cross Cathedral (Bazylika katedralna Podwyższenia Krzyża Świętego), which contains the Piast Chapel with the tomb of Jan II the Good, the last duke of Opole from the Piast dynasty

- The art nouveau Penny Bridge (Most Groszowy), currently named Green Bridge (Zielony Mostek)

- Opole Main Station, an eclectic building from early 20th century.

Museums

- Diocesan Museum (Muzeum Diecezjalne)

- Opole Regional Museum (Muzeum Śląska Opolskiego)

- Opole Village Museum (Muzeum Wsi Opolskiej)

- Central POW Museum (Centralne Muzeum Jeńców Wojennych)

Cemetery

- The Jewish Cemetery in Opole was established in 1822, and it is a peculiar pantheon of the Jews of Opole.[41][42]

Geography

Opole is one of the warmest cities in Poland. The national all-time heat record was measured in Prószków, near Opole. The climate is oceanic with sizeable continental influences.

| Climate data for Opole (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

19.9 (67.8) |

24.5 (76.1) |

29.3 (84.7) |

33.9 (93.0) |

36.0 (96.8) |

37.1 (98.8) |

37.9 (100.2) |

35.4 (95.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

37.9 (100.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.5 (36.5) |

4.3 (39.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

20.2 (68.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

8.2 (46.8) |

3.5 (38.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.5 (31.1) |

0.7 (33.3) |

4.1 (39.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

14.5 (58.1) |

9.6 (49.3) |

5.0 (41.0) |

0.8 (33.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.4 (25.9) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

8.5 (47.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

5.8 (42.4) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28.0 (−18.4) |

−29.7 (−21.5) |

−22.3 (−8.1) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−26.3 (−15.3) |

−29.7 (−21.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 31.5 (1.24) |

29.0 (1.14) |

35.2 (1.39) |

36.9 (1.45) |

62.6 (2.46) |

78.2 (3.08) |

89.4 (3.52) |

54.2 (2.13) |

56.7 (2.23) |

41.5 (1.63) |

37.8 (1.49) |

31.9 (1.26) |

585.0 (23.03) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 6.4 (2.5) |

6.0 (2.4) |

3.5 (1.4) |

0.9 (0.4) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.4 (0.2) |

2.4 (0.9) |

4.2 (1.7) |

6.4 (2.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 15.83 | 13.63 | 14.37 | 10.93 | 13.17 | 13.27 | 13.37 | 11.63 | 11.33 | 12.83 | 13.80 | 14.83 | 159.00 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0 cm) | 14.9 | 11.3 | 4.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 3.2 | 8.3 | 43.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84.0 | 80.4 | 75.3 | 68.9 | 71.8 | 72.1 | 71.3 | 71.9 | 78.0 | 81.8 | 85.0 | 85.1 | 77.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 56.1 | 77.6 | 129.4 | 197.5 | 239.4 | 243.0 | 257.2 | 247.4 | 170.0 | 118.2 | 66.9 | 49.6 | 1,852.3 |

| Source 1: Institute of Meteorology and Water Management[43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteomodel.pl (records, relative humidity 1991–2020)[51][52][53] | |||||||||||||

Education

- state-run universities and colleges:

- privately run colleges:

- Management and Administration College in Opole (Wyższa Szkoła Zarządzania i Administracji w Opolu)

- Bogdan Jański Academy (Szkoła Wyższa im. Bogdana Jańskiego)

- WSB Merito Universities - WSB Merito University in Wrocław,[54] departments of Economics

Politics

Members of Parliament (Sejm) elected from Opole constituency

- Danuta Jazłowiecka, PO

- Tadeusz Jarmuziewicz, PO

- Ryszard Knosala, PO

- Leszek Korzeniowski, PO

- Sławomir Kłosowski, PiS

- Teresa Ceglecka-Zielonka, PiS

- Mieczysław Walkiewicz, PiS

- Henryk Kroll, German minority

- Ryszard Galla, German minority

- Józef Stępkowski, Samoobrona

- Sandra Lewandowska, Samoobrona

- Tomasz Garbowski, SLD

- Marek Kawa, LPR

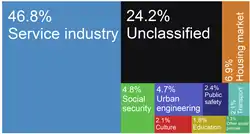

Economy

Opole is the Opole Voivodeship's centre for commerce, banking, industrial complexes and other major service sector industries.[55][56][57]

Prior to World War II, due to major limestone deposits in Opole's vicinity, the city developed as a centre for cement production in Germany, with the Cementownia "Odra" being active till this day. The French building materials company Lafarge is also active in the area, having its roofing division, Lafarge Roofing, together with its German subsidiary Schiedel (chimney manufacturing) based in Opole.[58]

Other companies in the city include: the German valve manufacturer Kludi; the German men's fashion manufacturer Ahlers and the American automotive manufacturer Tower Automative. As is the case with the entire Opole Voivodeship, there is a strong presence of food industry services in the city. The largest companies in the food sector include: Zott, the Dutch baby food and nutrition company Nutricia, part of the Danone food-products corporation.

Opole has branches of all major banks, including: PKO, Pekao, Deutsche Bank and Raiffeisen Zentralbank.

The retail sector in Opole includes major Metro AG brand stores: Metro Cash and Carry and Media-Saturn-Holding, as well as Real. The city has a plethora of other major supermarket chains, namely: the Polish supermarket chains Biedronka, Lidl, Aldi and Netto.[59] Other major brand stores include the shoe retailer Deichmann and Rossmann drugstores.[60]

Furthermore, the city has three major shopping centres. The Solaris Center, with a total of 86 shops, opened in May 2009 and is located in the centre of Mikołaj Kopernik Square. In the city's suburbs, by Wrocławska Street (ul. Wrocławska) is the location of Karolinka Shopping Centre (Centrum Handlowe Karolinka). The shopping centre, which opened in September 2008, has a total area of 38,000 m², with a total of 99 stores, including fashion, hardware and electronics stores. To the east of the city, by the National Road 46, is the smallest of the three shopping centres, Turawa Park, with a total of 50 stores. Other shopping centres include Galeria Opolanin, built between 1974 and 1981 and upon its completion, was the largest shopping centre in Poland.[61]

Sports

Among the city's most popular sports team are:

- Odra Opole – football club, playing in the Polish second division. From the 1950s to the 1980s the team competed in the country's top-flight, finishing 3rd in 1964.

- Orlik Opole – ice hockey club, playing in the Polish Hockey League, the country's top division.

- Kolejarz Opole – speedway club who race at the Marian Spychała Speedway Stadium and compete in the Polish leagues. In the 1970s and 1980s, the team competed in the country's top-flight, finishing 3rd in 1970.

- Gwardia Opole – handball club, playing in the Polish Superliga, the country's top division, and finishing 3rd in 1964 and, recently, in 2019.

Notable people

- Leo Baeck (1873–1956), rabbi

- Anna Brzezińska (born 1971), fantasy writer

- Jerzy Buzek (born 1940), academic and politician, President of the European Parliament, former Prime Minister of Poland

- Jan Fethke (1903–1980), film director

- Damian Grabowski (born 1980), mixed martial artist

- Jerzy Grotowski (1933–1999), theater director

- Danuta Jazłowiecka (born 1957), politician

- Jakub Kania (1872–1957), Polish poet and writer, soldier in the Silesian Uprisings

- Jan Kasprowicz (1860–1926), poet

- Paul Kleinert (1837–1920), German theologian

- Miroslav Klose (born 1978), football player (playing in the Germany national football team)

- Bronisław Koraszewski (1863–1924), Polish activist, founder of Gazeta Opolska

- Szymon Koszyk (1891–1972), reporter, teacher and Polish activist from Opole

- Andrzej Jerzy Lech (born 1955), artist and photographer

- Simon Bar Jona Madelka (before 1550–c. 1598), Czech composer

- Chester Marcol (born 1949), American football placekicker for the Green Bay Packers

- Rochus Misch (1917–2013), communications' chief of the Reichskanzlei and member of the Leibstandarte-SS Adolf Hitler

- Jacek Morajko (born 1981), cyclist

- Remigiusz Mróz (born 1987), writer

- Marcin Ociepa (born 1984), politician

- Edmund Osmańczyk (1913–1989), reporter, politician (6 times elected to the sejm and once to the senate)

- Emin Pasha (born Eduard Schnitzer) (1840–1892), explorer and governor of Africa

- Bolesław Polnar (born 1952), graphic artist and painter

- Joachim Prinz (1902–1988), rabbi, born here

- Oscar Slater (1872–1948), German/Scottish victim of miscarriage of justice

- Krzysztof Szramiak (born 1984), Polish weightlifter

- Bronisław Trentowski (1808–1869), Polish philosopher, pedagogist and journalist

- Vladislaus II of Opole, count palatine of Poland 1378

- Karolina Wydra (born 1981), actress

- Piotr Zioła (born 1995), rock singer

Twin towns – sister cities

Alytus, Lithuania

Alytus, Lithuania Bruntál, Czech Republic

Bruntál, Czech Republic Carrara, Italy

Carrara, Italy Grasse, France

Grasse, France Ingolstadt, Germany

Ingolstadt, Germany Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine Kuopio, Finland

Kuopio, Finland Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany

Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany Potsdam, Germany

Potsdam, Germany Roanoke, United States

Roanoke, United States Székesfehérvár, Hungary

Székesfehérvár, Hungary

Gallery

Jesuit College, now a regional museum

Jesuit College, now a regional museum Church of the Holy Trinity

Church of the Holy Trinity Rynek (Market Square) filled with historic townhouses

Rynek (Market Square) filled with historic townhouses Green Bridge

Green Bridge Młynówka Canal (Little Venice)

Młynówka Canal (Little Venice) Ceres Fountain

Ceres Fountain Opole Główne railway station

Opole Główne railway station John Paul II Library

John Paul II Library Church of St. Adalbert, also known as the "Church on the Rock" and "Church on the Hill"

Church of St. Adalbert, also known as the "Church on the Rock" and "Church on the Hill" Signs showing direction of twin cities

Signs showing direction of twin cities

Citations

Notes

- ↑

- Pronunciation:

- Polish: [ɔˈpɔlɛ] ⓘ

- German: Oppeln [ˈɔpl̩n];

- Silesian:

- Silesian PLS alphabet: Ôpole[2]

- Steuer's Silesian alphabet: Uopole

- Silesian German: Uppeln

- Czech: Opolí[3]

- Latin: Oppelia, Oppolia, Opulia[4][5]

- Pronunciation:

References

- 1 2 "Poland: Opole Voivodeship (Counties and Communes) - Population Statistics, Charts and Map".

- ↑ R. Szyma (28 December 2020). "_Nasz dōm – Gōrny Ślōnsk!". wachtyrz.eu.

- ↑ "Opolí". prirucka.ujc.cas.cz (in Czech).

- ↑ A. Wiśniewski. "Opole – miasto z różnych perspektyw". opole.pl (in Polish).

- ↑ G. Staniszewski (red.), B. Szafraniec, U. Zajączkowska, M. Krajewski, Opole: Urząd Miasta Opola, ISBN 978-83-87401-04-7

- ↑ "Opole - description, location, history". Mapofpoland.net. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "Local history - Information about the town - Opole - Virtual Shtetl". Archived from the original on 2016-10-09. Retrieved 2016-10-08.

- ↑ Witosławska, Agata. "Opole – history and song festivals". Poland.travel. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "Studia w Opolu. Polska Wenecja może zaoferować Wam nie tylko wspaniałe widoki, ale także cudowną atmosferę". Studiowac.pl – wyszukiwarka uczelni i katalog kierunków studiów, matura z polskiego, poradniki maturalne (in Polish). 30 July 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ Opole, Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich, Tom VII, nakł. Filipa Sulimierskiego i Władysława Walewskiego, 1880-1914

- ↑ B. Gediga, Początki i rozwój wczesnośredniowiecznego ośrodka miejskiego na Ostrówku w Opolu, Slavia Antiqua t. 16, Wrocław 1970.

- ↑ W. Dziewulski, F. Hawranek, Opole - Monografia miasta, Instytut Śląski Opole 1975, p. 57.

- ↑ This opinion is shared i.e. by W. Dziewulski, F. Hawranek, Opole - Monografia miasta, Instytut Śląski Opole 1975, p. 57 and G. A. Stenzel, Geschichte Schlesiens, T1. 1, Breslau 1853, p. 41. The opposite opinion is presented i.e. by K. Buczek, Targi i miasta na prawie polskim (okres wczesnośredniowieczny), Wrocław 1964, p. 114.

- ↑ W. Dziewulski, F. Hawranek, Opole - Monografia miasta, Instytut Śląski Opole 1975, pp. 58–60.

- ↑ W. Dziewulski, F. Hawranek, Opole - Monografia miasta, Instytut Śląski Opole 1975, p.78.

- ↑ W. Dziewulski, F. Hawranek, Opole - Monografia miasta, Instytut Śląski Opole 1975, p.159.

- ↑ "Historia Powiatu Prudnickiego - Starostwo Powiatowe w Prudniku". 2020-11-16. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 2021-12-07.

- 1 2 W. Dziewulski, F. Hawranek, Opole - Monografia miasta, Instytut Śląski Opole 1975, p. 263–268".

- ↑ T. Hunt Tooley, National Identity and Weimar Germany. Upper Silesia and the Eastern Border, 1918–1922, University of Nebraska Press, 1997, p. 15

- ↑ Spotkania z Zabytkami. 6, 2005, p. 21. (in Polish)

- ↑ Dorota Simonides, Jan Zaremba, Śląskie miscellanea: literatura-folklor, 2006, p. 82 (in Polish)

- ↑ Cygański, Mirosław (1984). "Hitlerowskie prześladowania przywódców i aktywu Związków Polaków w Niemczech w latach 1939-1945". Przegląd Zachodni (in Polish) (4): 24.

- 1 2 Cygański, p. 29

- ↑ Cygański, p. 30–31

- ↑ Cygański, p. 25

- 1 2 Cygański, p. 30

- ↑ Cygański, p. 32

- ↑ Cygański, p. 32–34

- ↑ Cygański, p. 33

- ↑ Cygański, p. 32–33

- ↑ Cygański, p. 32, 35

- ↑ Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 58.

- ↑ Cygański, p. 60–62

- ↑ Cygański, p. 59

- ↑ "Working Parties". Lamsdorf.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ "Opole (Opolskie) » mapy, nieruchomości, GUS, noclegi, szkoły, regon, atrakcje, kody pocztowe, wypadki drogowe, bezrobocie, wynagrodzenie, zarobki, tabele, edukacja, demografia".

- ↑ "Opolscy Kresowianie wciąż żyją wspomnieniami o rodzinnych stronach".

- ↑ "Rozporządzenie Rady Ministrów z dnia 19 lipca 2016 r. w sprawie ustalenia granic niektórych gmin i miast, nadania niektórym miejscowościom statusu miasta oraz zmiany nazwy gminy". isap.sejm.gov.pl. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "Opole się powiększa kosztem okolicznych wsi. Ich mieszkańcy protestują."To skok na kasę"". TVN24.pl. Retrieved 2017-10-04.

- ↑ "German minority in Poland on the Ministry of Interior and Administration webpage". 2.mswia.gov.pl. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ "JEWISH CEMETERY IN OPOLE (GRANICZNA STREET)". Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ "OPOLE: Opolskie". International Jewish Cemetery Project. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ↑ "Średnia dobowa temperatura powietrza". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ "Średnia minimalna temperatura powietrza". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ "Średnia maksymalna temperatura powietrza". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ "Miesięczna suma opadu". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ "Liczba dni z opadem >= 0,1 mm". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ "Średnia grubość pokrywy śnieżnej". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ "Liczba dni z pokrywą śnieżna > 0 cm". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ "Średnia suma usłonecznienia (h)". Normy klimatyczne 1991-2020 (in Polish). Institute of Meteorology and Water Management. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ "Opole Absolutna temperatura maksymalna" (in Polish). Meteomodel.pl. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ "Opole Absolutna temperatura minimalna" (in Polish). Meteomodel.pl. 6 April 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ "Opole Średnia wilgotność" (in Polish). Meteomodel.pl. 6 April 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ WSB University in Wrocław Archived 2016-03-01 at the Wayback Machine - WSB Universities

- ↑ "Nowe firmy Opole 2016, 2015, 2014 r., nowo rejestrowane firmy w Opolu i województwie opolskim". Coig.com.pl. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "Zainwestowali". Invest in Opole (in Polish). Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "OPOLE Firmy i Instytucje". Info-net.com.pl. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "Historia Opola". Opole.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "Wyborcza.pl". opole.wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "Drogeria Rossmann - województwo opolskie". Rossmann.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "Galeria Opolanin Opole". Galeria-opolanin.pl. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "Miasta partnerskie". opole.pl. Opole. Retrieved 2020-03-04.

Bibliography

- The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. "Opole". Columbia University Press. Accessed June 4, 2006.

External links

- Opole - Official Tourist Information

- Municipal website

- Urban development of Opole in the Historical-Topographical Atlas of Silesian Towns

- Jewish Community in Opole on Virtual Shtetl

- Webcam showing Krakowska Street in Opole (in Polish)

- CityOn.pl - things to do in Opole (in Polish)

- Culture: Amfiteart Opole

- Culture: KFPP Opole

.jpg.webp)