| Orangethroat darter | |

|---|---|

| |

| A male orangethroat darter | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Family: | Percidae |

| Genus: | Etheostoma |

| Species: | E. spectabile |

| Binomial name | |

| Etheostoma spectabile (Agassiz, 1854) | |

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

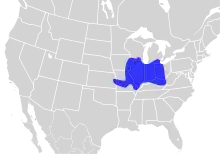

The orangethroat darter (Etheostoma spectabile) is a species of freshwater ray-finned fish, a darter from the subfamily Etheostomatinae, part of the family Percidae, which also contains the perches, ruffes and pikeperches. It is endemic to the central and eastern United States where it is native to parts of the Mississippi River Basin and Lake Erie Basin. Its typical habitat includes shallow gravel riffles in cooler streams and rocky runs and pools in headwaters, creeks, and small rivers, with sand, gravel, rubble, or rock substrates. It forages on the bottom for the aquatic larvae of midges, blackfly, mayfly and caddisfly, as well as isopods and amphipods. Spawning takes place in spring, the selected sites often being the upper stretches of riffles with sandy and gravelly bottoms interspersed with larger cobble. Reproductive success is high in this species. No particular threats have been identified, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature has assessed its conservation status as being of "least concern".

Geographic Distribution

The orangethroat darter is found in portions of the Mississippi River Basin and Lake Erie Basin of North America.[2] It is found in the eastern and western tributaries of the Mississippi River Basin from southeastern Michigan and Ohio to eastern Wyoming. Its range extends south to Tennessee and west to the northern section of Texas; Gulf drainages (Trinity River to San Antonio River) of Texas, mostly on Edwards Plateau.[2] Locally, the orangethroat darter is found regularly throughout middle Tennessee in appropriate, high quality habitats. This species is found locally in the Cumberland drainage below Cumberland Falls, and in the lower Tennessee drainage upstream to the Pickwick Reservoir area. It is most abundant in streams of the northern and western Highland Rim, isolated populations occur in the Reelfoot Lake vicinity with stream draining bluffs.[3]

Ecology

No quantitative diet analysis has been conducted on the orangethroat darter in Tennessee. However, in other populations tested, the diet was found to mainly include midge and blackfly larvae, mayfly nymphs, isopods, amphipods, and caddisfly larvae. but the composition varied seasonally and with age.[4] This species' habitat often includes slow to swift, shallow gravel riffles in cooler streams. Sometimes the orangethroat darter will inhabit rocky runs and pools, of headwaters, creeks, and small rivers, with sand, gravel, rubble, or bedrock substrates; spring runs or quiet backwaters in some areas. This species is most abundant in waters with a high alkalinity; it seems to avoid rivers with strong current. Eggs are laid in gravel in riffles. Young drift downstream into pools, sometimes move into smallmouth bass nests where they feed.[1] This fish mostly competes with other darters or minnows due to its size restriction and predators may consist of larger species in the particular stream like trout or smallmouth bass. Edie Marsh mentioned in her study in Texas of the orange throat darter that offspring from larger eggs tended to be larger at hatching than those from smaller eggs although there was no effect of egg size on time to hatching.[5] Marsh then continued to test these specimens under a starvation condition where she found offspring from larger eggs were larger at starvation and took longer to starve than those from smaller eggs.[5]

Life History

The orangethroat darter males are typically of smaller length than the females, yet they prefer smaller females. This is due to the sex ratio of abundance of this species being very male dominated, about seven to one.[5] According to Hubbs, et al., the season of E. spectabile is slightly earlier than that of E. caeruleum, usually beginning in mid to late March.[6] Ideal spawning habitat was at the upper ends of riffles with sandy and gravelly bottoms interspersed with larger cobble. Hubbs, et al. went on to state that gravid or pregnant female E. spectabile were reported to contain anywhere from twenty to two hundred and fifty eggs. The eggs of this particular species are tolerant of a wide range of temperature with good hatching success from 10 C to 27 C (50 F to 81 F).[7] The hatching success of this fish is relatively high as well has the yearling success due to its nature of seeking out large mouth bass nests for food and protection from predation. The orangethroat darter reaches reproductive maturity at the age of one year at a length of only 30 millimeters (1 1/8") or slightly smaller.[3] Throughout another study that took place in Kentucky by Small, it was noted that young was growing to a length of about 45 millimeters (1 3/4") within the first year and by the second year, it was reported that lengths of this species reached 60-70 millimeters (2 3/8" - 2 3/4"). Small also noted that the maximum total length is 74 millimeters (2 7/8") yet this species is often much smaller than that.[8]

Current Management

Etheostoma spectabile is listed as least concern in the entirety of it range due to its high abundance with few limiting factors. Currently, the largest threat to E. spectabile is run-off and pollution due to urbanization and urban sprawl. A study in Indiana found that the development of an interstate could potentially negatively affect the abundance of a number of fish species, including E. spectabile, because of decreasing water quality of the nearby creek.[9] Therefore, the monitoring of run-off and pollution draining into rivers and streams is important due to the adverse effects they could have on fish communities within particular watersheds. Currently, management plans consist of reducing nutrient, pesticide, and sediment loadings within such streams in a watershed.[10] This same study suggests conservation practices should be a combination of both physical habitat monitoring and water chemistry monitoring, because it would benefit fish communities within headwater streams more than just implementing one conservation practice or the other.[10] Although broad management plans are in place for many rivers and streams and their fish communities as a whole, no current management plans in place are specifically focusing on E. spectabile.

References

- 1 2 NatureServe (2013). "Etheostoma spectabile". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T202535A18230090. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T202535A18230090.en. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- 1 2 3 Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2019). spectabile"Etheostoma spectabile" in FishBase. December 2019 version.

- 1 2 Etnier, David A.; Starnes, Wayne C (1993). The Fishes of Tennessee (PDF). Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-26. Retrieved 2013-11-20.

- ↑ Gillette, David P (2012). "Effects of Variation among Riffles on Prey Use and Feeding Selectivity of the Orangethroat Darter Etheostoma spectabile". The American Midland Naturalist. 168 (1): 184–201. doi:10.1674/0003-0031-168.1.184.

- 1 2 3 Marsh, Edie (1986). "Effects of Egg Size on Offspring Fitness and Maternal Fecundity in the Orangethroat Darter, Etheostoma spectabile (Pisces: Percidae)". Copeia. 1986 (1): 18–30. doi:10.2307/1444883.

- ↑ Hubbs, C.; Stevenson, M. M.; Peden, A. E. (1968). "Fecundity and egg size in two central Texas darter populations". The Southwestern Naturalist. 13 (30): 1–323. doi:10.2307/3669223. JSTOR 3669223.

- ↑ Hubbs, C. (1961). "Developmental temperature tolerances of four etheostomine fishes occurring in Texas". Copia. 1961 (1): 95–198.

- ↑ Small, W. Jr. (1975). "Energy dynamics of benthic fishes in a small Kentucky stream". Ecology. 56 (4): 827–840. doi:10.2307/1936294. JSTOR 1936294.

- ↑ Ritzi, C.M., B. L. Everson, J. B. Foster, J. J. Sheets, and D. W. Sparks. 2004. Urban ichthyology: changes in the fish community along an urban-rural creek in Indiana. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science (113): 42-52.

- 1 2 Smiley, P.C., R. B. Gillespie, K. W. King, and C. Huang. 2009. Management implications of the relationships between water chemistry and fishes within channelized headwater streams in the Midwestern United States. Ecohydrology (2): 294-302.