| Orlando | |

|---|---|

Promotional poster | |

| Directed by | Sally Potter |

| Screenplay by | Sally Potter |

| Based on | Orlando: A Biography by Virginia Woolf |

| Produced by | Christopher Sheppard |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Aleksei Rodionov |

| Edited by | Hervé Schneid |

| Music by | David Motion Sally Potter |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Classics |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom France Italy Netherlands Russia |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $4 million[1] |

| Box office | $13 million[2] |

Orlando is a 1992 British period drama fantasy film[3] loosely based on Virginia Woolf's 1928 novel Orlando: A Biography, starring Tilda Swinton as Orlando, Billy Zane as Marmaduke Bonthrop Shelmerdine, and Quentin Crisp as Queen Elizabeth I. It was written and directed by Sally Potter, who also co-wrote the score with David Motion.[4]

Potter chose to film much of the Constantinople portion of the book in the isolated city of Khiva in Uzbekistan and made use of the forest of carved columns in the city's 18th century Djuma Mosque. Critics praised the film and particularly applauded its visual treatment of the settings of Woolf's novel. The film premiered in competition at the 49th Venice International Film Festival,[5] and was re-released in select U.S. cinemas in August 2010.[6][7]

Plot

The story begins in the Elizabethan era, shortly before the death of Queen Elizabeth I in 1603. On her deathbed, the queen promises an androgynous young nobleman named Orlando a large tract of land and a castle built on it, along with a generous monetary gift; both Orlando and his heirs would keep the land and inheritance forever, but Elizabeth will bequeath it to him only if he assents to an unusual command: "Do not fade. Do not wither. Do not grow old." Orlando acquiesces and reposes in splendid isolation in the castle for a couple of centuries during which time he dabbles in poetry and art. His attempts to befriend a celebrated poet backfire when the poet ridicules his verse. Orlando then travels as English ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. After years of diplomatic service, participates in a battle but flees after witnessing the first death. Waking seven days later, he learns something startling: he has transformed into a woman.

The now Lady Orlando comes home to her estate in Middle-Eastern attire, only to learn that she faces several impending lawsuits arguing that Orlando was a woman all along and therefore has no right to the land or any of the royal inheritance that the queen had promised. The succeeding two centuries tire Orlando; the court case, bad luck in love, and the wars of British history eventually bring the story to the present day (i.e., the early 1990s). Orlando now has a young daughter in tow and is in search of a publisher for her book. (The literary editor who judges the work as "quite good" is portrayed by Heathcote Williams—the same actor who played the poet who had, earlier in the film, denigrated Orlando's poetry.) Having lived a most bizarre existence, Orlando, relaxing with her daughter, points out to her an angel.

Differences from the novel

Director Potter described her approach to the adaptation as follows:

My task...was to find a way of remaining true to the spirit of the book and to Virginia Woolf's intentions, whilst being ruthless with changing the book in any way necessary to make it work cinematically...The most immediate changes were structural. The storyline was simplified [and] any events which did not significantly further Orlando's story were dropped.[1]: 14

The film contains some anachronisms not present in the novel. For example, upon Orlando's arrival in Constantinople in about the year 1700, England is referred to as a "green and pleasant land", a line from William Blake's Jerusalem, which in reality was not written until 1804.[8]

Potter argued that "whereas the novel could withstand abstraction and arbitrariness (such as Orlando's change of sex), cinema is more pragmatic."[1]: 14 She continued,

There had to be reasons—however flimsy—to propel us along a journey based itself on a kind of suspension of disbelief. Thus, Queen Elizabeth bestows Orlando's long life upon him...whereas in the book it remains unexplained. And Orlando's change of sex in the film is the result of his having reached a crisis point—a crisis of masculine identity.[1]: 14–15

At film's end, Orlando has a daughter, whereas in the novel she had a son.[1]: 15 Potter said that she intended Orlando's breaking the fourth wall to be an equivalent to Woolf's direct addresses to her readers,[lower-alpha 1] and that this was her attempt at converting Woolf's literary wit into a more 'cinematic' humour.[1]: 15 One obvious similarity remained, however: The film ends in its present day, 1992,[1]: 15 [lower-alpha 2] just as Woolf's novel ends in its present day, 1928.[9]

Cast

- Tilda Swinton as Orlando

- Quentin Crisp as Elizabeth I

- Jimmy Somerville as Falsetto / Angel

- John Wood as Archduke Harry

- John Bott as Orlando's Father

- Elaine Banham as Orlando's Mother

- Anna Farnworth as Clorinda

- Sara Mair-Thomas as Favilla

- Anna Healy as Euphrosyne

- Dudley Sutton as James I

- Simon Russell Beale as Earl of Moray

- Matthew Sim as Lord Francis Vere

- Charlotte Valandrey as Princess Sasha

- Toby Stephens as Othello

- Oleg Pogudin (credited as Oleg Pogodin) as Desdemona

- Heathcote Williams as Nick Greene / The Publisher

- Lothaire Bluteau as The Khan

- Thom Hoffman as William III

- Sarah Crowden as Mary II

- Billy Zane as Shelmerdine

- Ned Sherrin as Addison

- Kathryn Hunter as Countess

- Roger Hammond as Swift

- Peter Eyre as Pope

- Toby Jones as Second Valet

Production

When first pitching her treatment in 1984, Potter was told by "industry professionals" that the story was "unmakable, impossible, far too expensive and anyway not interesting."[1]: 16 Nevertheless, in 1988 she began writing the script and raising money.[1]: 16

Potter saw Swinton in the Manfred Karge play Man to Man and said that there was a "profound subtlety about the way she took on male body language and handled maleness and femaleness." In Potter's words, Quentin Crisp was the "Queen of Queens...particularly in the context of Virginia Woolf's gender-bending politics" and thus fit to play the aged Queen Elizabeth.

Poetry

Portions of the following texts are used:[10]

- The Faerie Queene by Edmund Spenser

- Shakespeare's Othello and Sonnet 29

- "Women" ("Sūrat an-Nisāʼ") from the Quran

- "The Indian Serenade" and The Revolt of Islam by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Music

The following songs are featured:

- Jimmy Somerville – "Eliza Is the Fairest Queen" (composed by Edward Johnson)

- Andrew Watts with Peter Hayward on harpsichord – "Where'er You Walk" (from Semele; composed by George Frideric Handel)

- Jimmy Somerville – "Coming" (composed by Potter, Jimmy Somerville, and David Motion)

- Anonymous – "Pavana"

Reception

Critical reception

Before Orlando's release in the United States in June 1993, Vincent Canby wrote in an effusively positive review:

This ravishing and witty spectacle invades the mind through eyes that are dazzled without ever being anesthetised. Throughout Ms. Potter's Orlando, as in Woolf's, there [is] a piercing kind of common sense and a joy that, because they are so rare these days in any medium, create their own kind of cinematic suspense and delightedly surprised laughter. Orlando could well become a classic of a very special kind—not mainstream perhaps—but a model for independent film makers who follow their own irrational muses, sometimes to unmourned obscurity, occasionally to glory.[11]

Canby, however, cautioned that while the novel stands on its own, he was not sure if the film does. He wrote, "Potter's achievement is in translating to film something of the breadth of Woolf's remarkable range of interests, not only in language and literature, but also in history, nature, weather, animals, the relation of the sexes and the very nature of the sexes."[11]

By contrast, Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times described Orlando as "hollow...smug...and self-satisfied" and complained that "any kind of emotional connection to match [Orlando's] carefully constructed look...is simply not to be had."[12]

By 2010, Orlando was received as part of Potter's successful oeuvre with Matthew Connelly and had one critic affirming in the first line of his review that "Rarely have source material, director, and leading actress been more in alignment than in Orlando, the 1992 adaptation of Virginia Woolf's novel, directed by Sally Potter and starring Tilda Swinton...Watching Orlando some 17 years after its U.S. theatrical run, however, proves a welcome reminder of just how skillfully they [Potter and Swinton] marshalled their respective gifts here, how openly they entered into a dialogue with Woolf's playful, slippery text."[13]

The film's score at Rotten Tomatoes is 84% based on 62 reviews, with an average rating of 6.7/10 and the consensus: "Orlando can't match its visual delights with equally hefty narrative, but it's so much fun to watch that it doesn't need to."[14]

Box office

The film grossed $5.3 million in the United States and Canada.[15] It also grossed $2 million in the United Kingdom; $1.9 million in Italy; $1.6 million in Germany and over $1 million in Australia. By October 1993 it had grossed $13 million.[2]

Awards

Orlando was nominated for Academy Awards for Production (Ben Van Os, Jan Roelfs) and Costume Design (Sandy Powell).[16] The film was also nominated for the 1994 Independent Spirit Awards' Best Foreign Film award.[17] At the 29th Guldbagge Awards, the film was nominated for the Best Foreign Film award.[18]

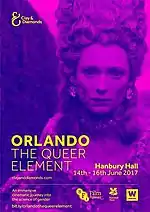

Orlando: The Queer Element

In 2017, the film was screened multiple times as part of a multi-media arts project Orlando: The Queer Element. The project explored issues of science and gender through history and was organised by the theatre company Clay & Diamonds, in association with organisations such as the BFI and the National Trust, with funding from the Wellcome Trust and Arts Council England.

A one-off immersive performance using five actors—some from the LGBT community—took place on Friday 24 March at the BFI Flare: London LGBT Film Festival, alongside a 25th Anniversary screening of the film.[19][20]

A separate series of performances was mounted in June by Clay & Diamonds with over 30 actors from the performance training company Fourth Monkey. Together they created a site-specific piece that was performed at the National Trust venues Hanbury Hall[21][22] and Knole house (the home of Vita Sackville-West, Woolf's lover, and the inspiration for Orlando). These performances were made for both the public and school audiences, with many of the performances featuring a screening of the film. The event also served part of the National Trust's "Prejudice and Pride" programme, which marked 50 years since the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in the United Kingdom with the passage of the Sexual Offences Act 1967.[23]

The project also featured the screening of a number of short art films created by Masters in Design students at the Royal College of Art as well as a series of scientific workshops and lectures.[24]

2020 Met Gala inspiration

Orlando, both the film and the novel, was the primary inspiration for both the 2020 spring exhibition of the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the 2020 Met Gala. The exhibition, entitled "About Time: Fashion and Duration", was specifically inspired by the "labyrinth" scene in Orlando, where Tilda Swinton runs through the labyrinth dressed in an 18th-century gown before she reappears dressed in mid-19th century garb.[25] Using that scene as the initial inspiration, curator Andrew Bolton took "Orlando’s concept of time and the manner in which she/he moves seamlessly through the centuries" to "trace more than a century and a half of fashion, illustrating how garments of the past influence the present."[25] Although the COVID-19 pandemic forced the cancellation of the Met Gala, the opening of the exhibition itself was postponed until October 2020.[26]

Notes

- ↑ See List of narrative techniques.

- ↑ From the press kit: "[T]he ending of the film needed to be brought into the present in order to remain true to Virginia Woolf's use of real-time at the end of the novel (where the story finishes just as she puts down her pen to finish the book). Coming up to the present day meant acknowledging some key events of the 20th century—the two world wars, the electronic revolution—the contraction of space through time reinvented by speed."

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Soto, Samantha (26 May 2010). "Orlando: Press Kit" (PDF) (Press release). New York, NY: Sony Pictures Classics. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- 1 2 "Box-office performance". Screen International. 26 November 1993. p. 13.

- ↑ Young, R. G., ed. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Film: Ali Baba to Zombies. New York: Applause. p. 468. ISBN 1-55783-269-2.

- ↑ Glaessner, Verina (1998). "Potter, Sally". In Unterburger, Amy L. (ed.). Women Filmmakers & Their Films. Detroit, MI: St. James Press. pp. 336–337. ISBN 1-55862-357-4.

- ↑ "Venezia, Libertà Per Gli Autori". La Repubblica. 31 July 1992. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ↑ "Orlando". www.sonyclassics.com.

- ↑ "Potter's Orlando set for US re-launch". Screen. 1 June 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ Dibble, Jeremy (3 March 2016). "Jerusalem: a history of England's hymn". The Conversation. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ Marik, Mikkonen Niina (December 2015). Modernism and Time in Virginia Woolf's Orlando: A Biography (PDF) (Master's thesis). Finland: University of Eastern Finland (School of Humanities, Philosophical Faculty). p. 46.

The only complete date given in the book is at the end, telling exactly when the narrative ends: "And the twelfth stroke of midnight sounded; the twelfth stroke of midnight, Thursday, the eleventh of October, Nineteen hundred and Twenty Eight".

- ↑ "Poetry & Lyrics". reocities.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- 1 2 Canby, Vincent (19 March 1993). "Review/Film Festival; Witty, Pretty, Bold, A Real She-Man". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ↑ Turan, Kenneth (25 June 1993). "Lush 'Orlando' Makes Its Point Once Too Often". Los Angeles Times. p. F8. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ↑ "Orlando - Film Review". Slant Magazine. 19 July 2010.

- ↑ "Orlando". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ↑ "Orlando (1993) - Release Summary - Box Office Mojo". www.boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ↑ "The 66th Academy Awards (1994) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ↑ Connors, Martin; Craddock, Jim, eds. (1999). "Orlando". VideoHound's Golden Movie Retriever 1999. Detroit: Visible Ink Press. p. 669. ISBN 1-57859-041-8. ISSN 1095-371X.

- ↑ "Orlando (1992)". Swedish Film Institute. 23 March 2014.

- ↑ "Interactive cinema event explores the queer element of Virginia Woolf's Orlando". www.bfi.org.uk. British Film Institute. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ↑ "Orlando: The Queer Element at BFI Flare".

- ↑ Bills-Geddes, Gary (31 May 2017). "The mysteries of gender at Hanbury Hall". Worcester News. Newsquest ltd. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ↑ Archive page of Orlando: The Queer Element at Hanbury Hall on The National Trust's website

- ↑ "Prejudice & Pride at Hanbury". National Trust.

- ↑ "Orlando: The Queer Element". Home.

- 1 2 Catherine St Germans (4 May 2020). "Inside the Costume Drama That Inspired This Year's Met Gala Exhibit". avenuemagazine.com. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ↑ Caroline Leaper (4 May 2020). "Everything you need to know about the Met Gala 2020 theme, "About Time: Fashion and Duration"". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

Further reading

- Barrett, Eileen; Cramer, Patricia, eds. (1995). "Two Orlandos: Controversies in Film & Fiction: Redirections: Challenging the Class Axe and Lesbian Erasure in Potter's Orlando, by Leslie K. Hankins". Re: Reading, Re: Writing, Re: Teaching Virginia Woolf. New York: Pace University Press. ISBN 978-0944473221. OCLC 32273822.

- Craft-Fairchild, Catherine (2001). ""Same Person...Just a Different Sex": Sally Potter's Construction of Gender in "Orlando"". Woolf Studies Annual. Pace University Press. 7: 23–48. ISSN 1080-9317. JSTOR 24906451.

- Hollinger, Karen; Winterhalter, Teresa (2001). "Orlando's Sister, Or Sally Potter Does Virginia Woolf in a Voice of Her Own". Style. Penn State University Press. 35 (2): 237–256. JSTOR 10.5325/style.35.2.237.

- Winterson, Jeanette (3 September 2018). "'Different sex. Same person': how Woolf's Orlando became a trans triumph". The Guardian.