| Ottoman conquest of Lesbos | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Expansion of the Ottoman Empire in Europe | |||||||

Towers of the Castle of Mytilene | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Knights Hospitaller | Ottoman Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Niccolò Gattilusio Luchino Gattilusio |

Mehmed the Conqueror Mahmud Angelović | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

Location of Mytilene and Lesbos within Greece | |||||||

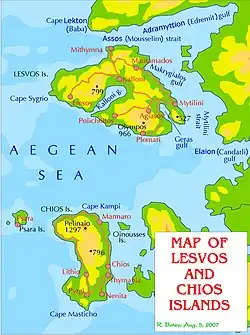

The Ottoman conquest of Lesbos took place in September 1462. The Ottoman Empire, under Sultan Mehmed II, laid siege to the island's capital, Mytilene. After its surrender, the other forts of the island surrendered as well. The event put an end to the semi-independent Genoese lordship that the Gattilusio family had established in the northeastern Aegean since the mid-14th century, and heralded the beginning of the First Ottoman–Venetian War in the following year.

In the mid-14th century, the Gattilusio family had established an autonomous lordship under Byzantine suzerainty on Lesbos. By 1453, the Gattilusio domains had come to include most of the islands in the northeastern Aegean. In the aftermath of the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, however, Mehmed II began reducing the Gattilusio holdings. By the end of 1456, only Lesbos remained in Gattilusio hands, in exchange for an annual tribute to the Sultan. In 1458 Niccolò Gattilusio seized control of the island from his brother, and began preparing for an eventual Ottoman attack. Despite his appeals, however, no help was forthcoming from other Western powers. Mehmed II began his campaign against Lesbos in August 1462, and the Ottomans landed on the island on 1 September. After a few days of skirmishing, the Ottomans brought up their artillery and began bombarding the Castle of Mytilene. By the eighth day, the Ottomans had captured the harbour fortifications, and two days later, they seized the lower town of Melanoudion. At this point, panic set in among the defenders, and their will to continue resisting collapsed.

Niccolò Gattilusio surrendered the castle and the rest of the island on 15 September, on promises of receiving estates of equivalent value. He was taken to Constantinople, where he was soon strangled. Despite promises, many of the defenders were executed, and a large part of the inhabitants were carried off as slaves, as servants in the Sultan's palace, or to help repopulate Constantinople. Ottoman rule on Lesbos lasted, with minor interruptions, until 1912.

Background: the Gattilusi and the Ottomans

During the Middle Ages, the island of Lesbos belonged to the Byzantine Empire. In the 1090s, the island was briefly occupied by the Turkish emir Tzachas. In the 12th century, the island became a frequent target for plundering raids by the Republic of Venice. After the Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) the island passed to the Latin Empire, but was reconquered by the Empire of Nicaea sometime after 1224. In 1354, it was granted as a fief to the Genoese Francesco I Gattilusio.[2] The Gattilusi also ruled Old Phocaea on the Anatolian mainland and the town of Ainos in Thrace, but by the 1430s, with the precipitate decline of Byzantine power, they had also seized Thasos and Samothrace.[3]

The Fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the young and ambitious Ottoman sultan Mehmed II was a turning point for the wider region.[4] The Gattilusi took advantage of the event to seize the island of Lemnos,[5] but the Sultan now demanded of the rulers of Lesbos an annual tribute of 3,000 gold coins, and a further 2,325 gold coins for Lemnos.[6] The position of vassalage was confirmed in 1455, when an Ottoman fleet under Hamza Bey toured the islands of the eastern Aegean: Domenico Gattilusio, the ruler of Lesbos, sent his Greek secretary, the historian Doukas, to meet the fleet with rich gifts and protestations of friendship and devotion.[7] Domenico had recently succeeded his father; when he sent Doukas to the Sultan with the usual tribute shortly after Hamza's visit, Doukas was met with the demand that Domenico himself come before Mehmed to have his succession confirmed. Domenico complied, but was forced to cede Thasos, accept an increase in the tribute for Lesbos to 4,000 gold coins, and undertake to pursue the Catalan pirates that infested the Anatolian shore opposite Lesbos.[8][9]

This did not prevent the Sultan from seizing Old Phocaea in December, or attacking the domains of Domenico's cousin, Dorino II Gattilusio, in January 1456: Mehmed himself captured Ainos, while his admiral Yunus Pasha took the islands of Imbros and Samothrace.[9][10] Lemnos, ruled by Domenico's younger brother Niccolò Gattilusio, was also lost when the local population rebelled in spring 1456 and called for Ottoman aid.[11][12] Lesbos itself was spared the same fate, for the time being, partly due to the general impotence of the Christian powers in the Aegean posing no immediate threat, and partly because Mehmed's attention was diverted north, to his wars with Serbia and Hungary.[13] In the autumn of 1456, a Papal squadron under Cardinal Ludovico Trevisan captured the islands of Lemnos, Thasos, and Samothrace.[14][15] Although the Gattilusi had nothing to do with this, in summer 1457 Mehmed sent his fleet to attack Lesbos. The Ottomans' attack on Methymna failed, however, in the face of determined resistance, and with the aid of Trevisan's ships.[15][16]

In late 1458, Niccolò Gattilusio, who had found refuge on Lesbos, deposed and strangled his older brother, usurping rule over the island. Along with Niccolò's toleration of the Catalans' piratical activities, this served as a perfect pretext for Mehmed to capture Lesbos.[17][18] In preparation for the upcoming campaign, the Sultan began an expansion of his fleet, and initiated extensive works around Constantinople and the Dardanelles, in order to secure an impregnable base of operations for his navy.[18] Niccolò Gattilusio sent several envoys to seek aid from Genoa, the Papacy, and other European states, but to little avail. Political rivalries between the Genoese families meant that neither the metropolis, nor the neighbouring Genoese colony of Chios, which had formerly undertaken to provide 300 men when Lesbos was threatened by Ottoman attack, were willing to come to the aid of the Gattilusi.[19][20] In the meantime, the Ottomans succeeded in recovering the islands lost to Trevisan (1459) and in subduing the Byzantine Despotate of the Morea (1460), cementing their control over mainland Greece. The last Despot of the Morea, Demetrios Palaiologos, was given the former Gattilusi domains as an appanage.[21] Niccolò nevertheless took care to strengthen the Castle of Mytilene, hoarding supplies and digging "trenches, fossettes, and earthen mounds", according to Doukas;[22] activity which was probably the occasion for an inscription incorporated in the castle walls and dated to 1460.[19]

Conquest of Lesbos

Opposing forces

In August 1462, Mehmed crossed over to Anatolia. After visiting the ruins of Troy—where, according to Kritoboulos, he was inspired to consider himself the avenger of the ancient Trojans against the Greeks—he marched to Assos, on the shore across from Lesbos. A contemporary Hospitaller account, written a few weeks later, puts his army at 40,000 men. The army was accompanied by a powerful fleet, led by Mahmud Pasha.[19][23] Sources differ as to its strength and composition: the Hospitaller account records 8 ships "armed with siege engines" (probably cannon), 25 galleys and 80 smaller vessels; the Roman Catholic archbishop of Mytilene, Benedetto, in a letter, records 5 armed ships, 24 galleys, and 96 fustas; Stefano Magno writes of 6 armed ships, 12 galleys, and 47 fustas; Doukas records 7 transport ships and 60 galleys; Laonikos Chalkokondyles records 25 galleys and 100 smaller vessels; Venetian reports speak of 65 vessels in total; while Kritoboulos raises their number to 200.[24]

Doukas places the defenders at 5,000, but Archbishop Benedetto claims that only 1,000 were present; among them 70 Knights Hospitaller and 110 Catalan mercenaries.[25][26] According to Doukas, the town of Mytilene harboured a civilian population of around 20,000.[22] The defenders further hoped for the assistance of the Venetians. A Venetian fleet under Vettore Cappello was nearby at Chios, but its commander was under strict instructions not to do anything that might provoke a war with the Ottomans. After the siege began, Cappello with his 29 galleys sailed towards Lesbos, and could easily have overwhelmed the Turkish fleet, whose crews had gone ashore to assist in the siege, but refrained from doing so.[27][28]

Siege of Mytilene

On 1 September, the fleet under Mahmud Pasha arrived at the island, docking in the harbour of St. George. Niccolò sent envoys to enquire as to the reason for their presence, since he had kept up the payment of tribute. Mahmud Pasha replied by demanding the surrender of Mytilene and the entire island. Mehmed himself crossed over with his army to the island via Agiasmati, and repeated his demand to Niccolò, but the latter replied that he would submit only to force. Mahmud Pasha then persuaded the Sultan to return to Anatolia and leave the siege to him, lest the Venetian fleet cut him off on Lesbos.[29][25]

The Ottoman admiral disembarked raiders, who ravaged the countryside, but captured few inhabitants, as most remained in the island's forts. After four days, six large cannon arrived, each capable of throwing missiles weighing over 700 pounds (320 kg). Three were emplaced at the soap works near the city wall, one at St. Nicholas, one at St. Kali, and one in the suburbs opposite a barbican tower, held by a monk and a Knight Hospitaller. Stones were piled up in front of them to protect them from the defenders' missiles. The bombardment lasted for ten days, and wrought great damage to the walls: the tower of the Virgin and the adjacent section of walls were reduced to ruins; while the St. Nicholas cannon was so effective against the tower guarding the harbour, that no defender dared approach it. The Turks captured the half-demolished tower on the eighth day and raised their red banners on top of it.[29]

The Ottomans then concentrated their efforts against the lower castle, known as Melanoudion. This was defended by Niccolò's cousin, Luchino Gattilusio. His more experienced lieutenants suggested setting it on fire and abandoning it, lest the Turks capture it and use it to capture the citadel. Luchino, however, insisted that he could hold the position. He did indeed hold for five days against repeated Ottoman attacks, although the Turks once succeeded in climbing the walls and carrying off an Aragonese flag as a trophy. On the next day, however, a massive assault by 20,000 Ottomans broke through, and drove the remaining defenders into the citadel. Luchino himself barely escaped, sword in hand, and his report of the Ottoman breakthrough terrified the populace who had taken refuge in the citadel.[30]

Their panic was increased by the fire of a huge mortar, which destroyed entire houses, together with those sheltering in them, and drove defenders from the walls, so that they had to be induced by large sums of money to brave the Ottoman artillery fire and repair the breaches in the walls. With suspicions circulating that Luchino and the castle commander had shown Mahmud Pasha the weak sections of the wall, discipline broke down completely. The soldiers broke into warehouses and looted them, becoming drunk with wine and consuming provisions that would have allowed the castle to hold for an entire year. When the Janissaries moved into the breaches, they met scant resistance. As William Miller comments, "though well provided with food and engines of war, the place lacked a brave and experienced soldier, who would have inspired the garrison with enthusiasm", and after a council, it was decided to surrender to the Sultan, provided their lives and properties were respected.[31][32]

Surrender and aftermath

Mahmud Pasha drew up a document outlining the terms of surrender, and swore by his sword and by the Sultan's head that their lives would be safe. Niccolò also demanded that he be given, in recompense, a domain of equivalent value. Learning of the surrender, Mehmed again crossed to the island, where he remained for four days. Accompanied by the notables of Mytilene, Niccolò surrendered the keys of the fortress to the Sultan, and begged for his forgiveness. Mehmed accepted, and instructed him to order the surrender of the other forts on the island—Methymna, Eressos, and Agioi Theodoroi (probably near Antissa)—as well. Niccolò complied, sending a letter with his seal to the forts, urging their garrisons to submit.[1][33][34] The garrison of Agioi Theodoroi sent emissaries to Cappello offering to surrender the fort to Venice instead, but he refused.[27][35] After allowing his troops to celebrate their victory in a drunken feast, in which the remaining houses of the Melanoudion quarter were burned down, Mehmed installed a garrison of 200 Janissaries and 300 irregular infantry (azaps) as a garrison in Mytilene, and entrusted its governance to the Persian sheikh Ali al-Bistami.[1][36]

Although the lives of all people on the island had been guaranteed, some 300 Italian soldiers were executed as pirates by being cut in half—the Sultan reportedly remarked that he thus honoured Mahmud Pasha's promise to "spare their heads".[1][36] The civilian population was not harmed at first, but on 17 September, the inhabitants of Mytilene were ordered to parade in front of the Sultan and three clerks, who recorded their names: some 800 boys and girls were selected for service in the Sultan's palace, while the remainder of the population was divided into three: the poorer and most frail of the inhabitants were allowed to remain in their homes, but the strongest and healthiest were sold off in auction as slaves to the Janissaries, and the third portion, including the island's nobility, were shipped off to repopulate Constantinople.[33][36][37] Altogether, some 10,000 inhabitants of the island were violently uprooted from their homes, some of whom perished in the overcrowded ships conveying them to Constantinople and the slave markets.[36] Niccolò Gattilusio himself was also taken to Constantinople, along with his cousin Luchino. They converted to Islam in an effort to save their lives, but were soon after strangled on Mehmed's orders.[38][39]

When the First Ottoman–Venetian War broke out in the next year, the former Gattilusio domains were an obvious target for the Christian fleets. But although the Venetians captured Lemnos in 1464, followed by Imbros, Tenedos, and Samothrace, these conquests proved ephemeral, as they were either recaptured by the Turks or abandoned at war's end. In April 1464, the Venetians under Orsato Giustiniano laid siege to Mytilene, but were forced to withdraw after six weeks of fruitless attacks, taking as many of the Christian inhabitants with them as they could. The island remained under Ottoman rule for four and a half centuries, until captured by the Kingdom of Greece in 1912, during the First Balkan War.[40]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Babinger 1978, p. 211.

- ↑ Gregory 1991, p. 1219.

- ↑ Wright 2014, p. 61.

- ↑ Wright 2014, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Wright 2014, p. 68.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, pp. 103, 132.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, p. 130.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, pp. 132–133.

- 1 2 Wright 2014, p. 69.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ Wright 2014, pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, p. 136.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, pp. 145–146, 150.

- 1 2 Wright 2014, p. 71.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Miller 1921, pp. 342, 346.

- 1 2 Babinger 1978, p. 209.

- 1 2 3 Miller 1921, p. 345.

- ↑ Wright 2014, pp. 72–73, 74.

- ↑ Wright 2014, p. 73.

- 1 2 Magoulias 1975, p. 261.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, pp. 209–210.

- ↑ Wright 2014, p. 74 (note 226).

- 1 2 Babinger 1978, p. 210.

- ↑ Wright 2014, p. 74 (note 227).

- 1 2 Miller 1921, p. 349.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, pp. 212–213.

- 1 2 Miller 1921, p. 346.

- ↑ Miller 1921, pp. 346–347.

- ↑ Miller 1921, p. 347.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, pp. 210–211.

- 1 2 Wright 2014, p. 75.

- ↑ Miller 1921, pp. 347–348.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, p. 213.

- 1 2 3 4 Miller 1921, p. 348.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Babinger 1978, p. 212.

- ↑ Miller 1921, pp. 348–349.

- ↑ Miller 1921, pp. 349–350.

Sources

- Babinger, Franz (1978). Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time. Bollingen Series 96. Translated from the German by Ralph Manheim. Edited, with a preface, by William C. Hickman. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. OCLC 164968842.

- Gregory, Timothy E. (1991). "Lesbos". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 1219. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Magoulias, Harry, ed. (1975). Decline and Fall of Byzantium to the Ottoman Turks, by Doukas. An Annotated Translation of "Historia Turco-Byzantina" by Harry J. Magoulias, Wayne State University. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-1540-8.

- Miller, William (1921). "The Gattilusj of Lesbos (1355–1462)". Essays on the Latin Orient. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 313–353. OCLC 457893641.

- Wright, Christopher (2014). The Gattilusio Lordships and the Aegean World 1355-1462. Leiden and Boston: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-26481-6.