| Owlpen Manor | |

|---|---|

Owlpen Manor from the south, with Court House (left) and church | |

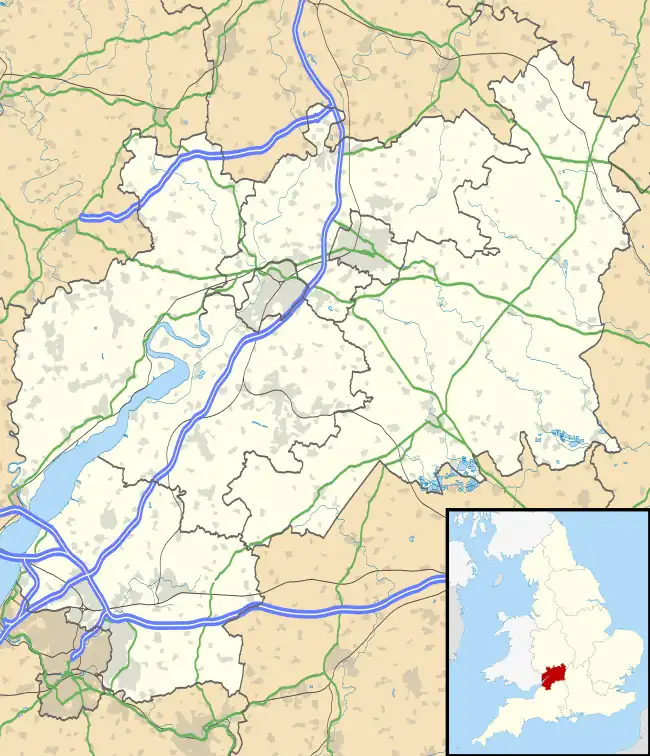

Location within Gloucestershire | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Tudor vernacular |

| Town or city | Owlpen |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°41′1″N 2°17′27″W / 51.68361°N 2.29083°W |

| Construction started | 1450 |

| Completed | 1616 |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | Cotswold stone cruck trusses stone tiled roof |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Norman Jewson (1926 repairs) |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Owlpen Manor |

| Designated | 23 June 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1152317 |

| Official name | Owlpen Manor |

| Designated | 28 February 1986 |

| Reference no. | 1000480 |

Owlpen Manor is a Tudor Grade I listed manor house of the Mander family, situated in the village of Owlpen in the Stroud district in Gloucestershire, England. There is an associated estate set in a valley within the Cotswold Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The manor house is about 1 mi (1.6 km) east of Uley, and 3 mi (4.8 km) east of Dursley.

History

The manor house is of medieval origins, incorporating fabric dated by dendrochronology to c. 1270. It was largely built and rebuilt in the Tudor period by the Daunt family between 1464 and 1616. Since then it has not seen significant development, except for some improvements early in the 18th century, when the east wing of the house, together with the gardens, church and Grist Mill, were reordered by Thomas Daunt IV between 1719 and 1726.[1][2]

Medieval period

Owlpen (pronounced locally "Ole-pen") derives its name, it is thought, from the Saxon thegn, Olla, who first set up his pen, or enclosure, by the springs that rise under the foundations of the manor, about the 9th century.[3]

There are records of the de Olepenne family (who may have named themselves after the place) settled at Owlpen by 1174. They were local landowners, benefactors to abbeys and hospitals, and henchmen to their feudal overlords, the Berkeleys of Berkeley Castle, whose wills and charters they regularly attest as their attorneys and witnesses.[1] They held Owlpen of the Berkeleys as a sub-manor at half a knight's fee and for a rent of 5s. paid to Wotton manor.[4]

Tudor period

In 1464 the male line failed after twelve generations of Olpennes and the manor and lands passed to the Daunt family on the marriage of Margery de Olepenne to John Daunt of Wotton-under-Edge.[5] The Daunts were clothiers who had been settled in Wotton-under-Edge since the 14th century.[6] They later acquired land as planters in Munster, Ireland, where by 1595 they had their principal estates at Gortigrenane Castle, near Carrigaline, and at Tracton Abbey, near Kinsale, both in County Cork. The Daunts altered the medieval manor house, inserting the ceiling in the great hall (dated 1523) and rebuilding the parlour/ solar block in the west wing (1616).[1] This followed a celebrated law case between the Daunts and John Bridgeman, who had claimed possession in right of his wife, Frances Daunt, following the death of her brother Giles in 1596. He became embroiled in a dispute with her uncle Thomas Daunt over the manor of Owlpen, but lost the case when he was accused of forging deeds before Sir Edward Coke, Chief Justice.[4] The manor was to continue in the Daunt family until the male line failed for a second time on the death of Thomas Daunt VI in 1803.[7]

Nineteenth century

In the nineteenth century, the fortunes of the manor suffered after the Stoughton family, Anglo-Irish landowners from County Kerry, inherited by marriage in 1815.[8] They built a new mansion c. 1848, called Owlpen House, a mile to the east of the original settlement, to the Italianate designs of Samuel Sanders Teulon. It was demolished in 1955–6, although outbuildings including the gas works, lodges and stable block remain. The Church of the Holy Cross behind the manor house, of medieval origins, was rebuilt in two phases in 1828 and 1874.[9]

Twentieth century

Towards the end of the 19th century, the old manor became an icon of the Arts and Crafts movement.[10][11] It was described by contemporary writers such as Henry Avray Tipping,[12] Christopher Hussey and the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne as an 'incomparable paradise', set in its remote valley as a Sleeping Beauty uninhabited for nearly a hundred years, a picturesque ruin, much decayed and overrun with ivy, and dwarfed by enormous yew trees.[13] After the First World War, there was concern for its survival and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings recommended that it should be vested in the National Trust, which however had no funds available for its repair.[14][15]

Finally, in 1924–25, the Owlpen estate was sold for the first time in nearly one thousand years. The future of the manor house was assured when it was acquired and repaired by Norman Jewson, a Cotswold Arts and Crafts movement architect who had worked with Ernest Gimson and the brothers Sidney and Ernest Barnsley (who was his father-in-law) in Sapperton.[16] In 1930, his friend, the artist F. L. Griggs dedicated his etching of Owlpen Manor to Jewson, who had 'saved this ancient house from ruin'.[17] Jewson has documented his repair work in his classic memoir, By Chance I did Rove (1951, twice reprinted).

Owlpen Manor was designated by Historic England as a grade I listed building on 23 June 1952.[18]

Owlpen today

Owlpen Manor is the Gloucestershire home of Sir Nicholas and Lady Karin Mander, and their family.[19] Since 1974 they have repaired the manor house and outbuildings, with the cottages and estate.[20] They have re-created the formal Stuart gardens and introduced family and associated Cotswold Arts and Crafts collections.

The manor contains a series of rare painted cloth wall-hangings dated about 1700, illustrating the life of Joseph,[21] as well as several notable features, including Tudor wall paintings, panelling and plasterwork.

Nicholas Mander's father, the third Mander baronet of The Mount, died in 2006. The Mander family gave Wightwick Manor to the National Trust in 1937.[22]

The manor house and gardens have been open to the public since 1966.[23]

Gardens

The formal terraced gardens with yew topiary are listed by Historic England Grade II. Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, the landscape historian, stated they represented one of the earliest continuously cultivated domestic gardens in England, laid out within late medieval stone walls.[24] They were probably reordered in their present form with their hanging terraces, defining topiary and yew parlour in early Stuart times, about 1620.[7] They were admired as a romantic survival in the 20th century by many distinguished garden writers, including Gertrude Jekyll, who published drawings, plans and photographs in 1914,[25] and Vita Sackville-West.[26] They have been restored and extended with box parterres, extensive tree planting and a walk around the Georgian mill pond and pear lake, since 1980.

Owlpen estate

The Owlpen estate, for many years managed on organic and sustainable principles, consists of species-rich permanent pasture and meadowland fringed by ancient woodland surrounding Owlpen Manor, and traditional farm buildings and cottages. Strip lynchets on the estate date to medieval times.

Nine historic cottages on the estate, including a Grist Mill (1728), Court House or Banqueting House (1620s), Tithe Barn (1446),[27] and weavers' cottages, have been available for holiday accommodation since the 1970s.

There is a restaurant in the late medieval cyder house, dated 1446,[28] which was extended using pole building framing techniques as a venue for weddings, concerts and events in 2020.

Media

Owlpen Manor has been the inspiration and title of a number of 20th-century poems, including 'Owlpen Manor' by U. A. Fanthorpe and verses by John Burnside and Reginald Arkell. The house is reputed to have inspired scenes in novels by John Buchan and Wolfgang Hildesheimer, and more recently in the romantic fictions of Kate Riordan, The Girl in Photograph, (Penguin Books, 2015),[29][30] Dinah Jefferies, The Tea Planter's Wife (Penguin Books, 2015),[31] and Katie Fforde.

In recent years, Owlpen Manor has been used as the location for a number of TV feature films, game shows and documentaries. They include Most Haunted (Series 4, 2004); The Fly and the Eagle (a BBC drama about the romance of Bristol poet laureate Robert Southey and Caroline Anne Bowles); The Trouble with Home (a documentary about the Manders at Owlpen made for HTV West); What the Tudors did for us; Countryfile; The Other Boleyn Girl; Watercolour Challenge; as well as antiques, cookery, gardening, travel, and art programmes. The holiday cottages and restaurant featured on BBC1's flagship Holiday programme, presented by John Cole and introduced by Jill Dando.

Owlpen Manor appeared as Bramscote Court in the BBC's period drama adaptation of Tess of the d'Urbervilles (2008), starring Gemma Arterton and Eddie Redmayne and (briefly) in Becoming Jane, on the life of novelist Jane Austen. In 2017, the manor house and estate were used as one of the principal locations for the period drama film Phantom Thread starring Daniel Day-Lewis and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson.[32] A cottage at Owlpen was chosen for the press interview in September 2005, subsequently shown on Netflix,[33] with Samantha Lewthwaite, a British jihadist known as "the White Widow".[34][35]

Quotes

- "The loveliest place in England" – Fodor's Britain Guide, 2002

- "The epitome of the English village" – HRH The Prince of Wales, A Vision of Britain, 1989

- "Owlpen in Gloucestershire —ah! What a dream is there!" – Vita Sackville-West, English Country Houses, 1941

- "The ruinous little old manor-house with its old hanging gardens of the 16th or 17th century, tidy & sweet & splendid ... a paradise incomparable on earth. Only a poet could describe it" – Algernon Charles Swinburne letter to William Morris, 28 October 1894

Literature

- Nicholas Mander, Varnished leaves : a biography of the Mander family of Wolverhampton, 1750–1950. Dursley: Owlpen Press. 2004. ISBN 0-9546056-0-8.

- Nicholas Mander, Owlpen Manor, Gloucestershire: a short history and guide to a romantic Tudor manor house in the Cotswolds. (current edition: 2006). OCLC 57576417

- Nicholas Mander, Country Houses of the Cotswolds (Aurum Press, 2008) ISBN 1845133315

- Norman Jewson, By Chance I did Rove (Cirencester, 1951, 1973; Barnsley 1986)

- Nicholas Kingsley, The Country Houses of Gloucestershire, Volume One, 1500-1660 (1989), pp. 142-4

- Hugh E. Pagan, Owlpen Manor (1966, reprinted 1975)

- The Rev. John Daunt, Some Account of the Family of Daunt (Newcastle, 1881; Scarborough, 1899)

References

- 1 2 3 Mander, Nicholas (2006). Owlpen Manor: A short history and guide. Owlpen Press. pp. 37–8. ISBN 0-9546056-1-6.

- ↑ Plans and accounts by Thomas Daunt, 1719-39 (D979a E3, E6-8), (Gloucester Archives)

- ↑ Smith, A.H. (1964). The Place Names of Gloucestershire: Part II. Cambridge. p. 244.

- 1 2 Smyth, John (1885). Description of the Hundred of Berkeley. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. p. 312.

- ↑ Greenwood, Charles (1977). Famous Houses of the West Country. Kingsmead. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0901571878.

- ↑ The Rev. John Daunt, Some Account of the Family of Daunt (Newcastle, 1881; Scarborough, 1899)

- 1 2 "Owlpen Manor Park and Garden". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 25 August 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ↑ Cooke, Robert (1957). West Country Houses. Batsford. pp. 86–87.

- ↑ • Gloucestershire: the Cotswolds, David Verey, Pevsner Architectural Guides: The Buildings of England, Penguin, 1970, ISBN 0-14-071040-X, pp. 415–417.

- ↑ "Owlpen Manor". Stone Art. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ↑ Mander, Nicholas (2006). Owlpen Manor: A short history and guide. Owlpen Press. pp. 55, 67. ISBN 0-9546056-1-6.

- ↑ Tipping, Henry Avray (1929). English Homes: Period III, vol 1. London: Country Life.

- ↑ Morris, May (1936), William Morris: artist, writer, socialist, p. 647

- ↑ Mander, Nicholas (2006). Owlpen Manor. Owlpen Press. pp. 44–5.

- ↑ Case files of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, London

- ↑ Musson, Jeremy (2018). Secret Houses of the Cotswolds. Frances Lincoln. pp. 90–99. ISBN 978-0711239241.

- ↑ Comstock, Francis (1966). A Gothic Vision: F.L. Griggs and his work. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum. p. 203.

- ↑ "Owlpen Manor". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ↑ Mosley, Charles, editor, Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, 107th edition, 3 volumes (Burke's Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 2003), volume 2, page 2589, sub Mander baronetcy of the Mount [U.K.], cr. 1911.

- ↑ Tyzack, Anna (4 March 2018). "Great Estates: inside the 'haunted' Tudor country house which starred in Phantom Thread". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ↑ Mander, Nicholas (Autumn 1997). "Painted Cloths: History, Craftsmen and Techniques". Textile History. 28 (2): 119–48.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the Mander Family". History website. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ↑ Hugh E. Pagan, Owlpen Manor (guidebook, 1966)

- ↑ Jellicoe, Geoffrey (1927). Gardens and Design. Ernest Benn. pp. 111–13.

- ↑ Jekyll, Gertrude and Weaver, Lawrence. Gardens for Small Country Houses. (London: Country Life, 1914).

- ↑ Sackville-West, Vita (1941). The English Country House. Collins.

- ↑ N.W. Alcock, Cruck Construction: An Introduction and Catalogue, 1981)

- ↑ Bridge, ‘Dr M.C., The Dendrochronological Dating of Timbers from the Barn at Owlpen Manor, Gloucestershire (ST 801 984)’, Oxford Dendrochronology Laboratory Report 2017/16

- ↑ "The Girl in the Photograph by Kate Riordan Weekend at Owlpen Manor". Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ https://adam-hinks.squarespace.com/literature/?offset=1472034209521

- ↑ "Booktrail: The Tea Planter's Wife by Dinah Jefferies | The Bookseller". thebookseller.com. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ↑ "Oscar-winner Daniel Day-Lewis said to be filming new movie at Owlpen Manor in Uley". Gazette Series. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ↑ https://www.netflix.com/gb/title/81013210

- ↑ "Terrorist's widow". The Yorkshire Post. 24 September 2005. p. 1.

- ↑ Herbert, Ian (24 September 2005). "Portrait of bomber as a dupe fails to convince bereaved". The Independent. p. 16.