Paramārtha (Sanskrit, Devanagari: परमार्थ; traditional Chinese: 真諦; simplified Chinese: 真谛; pinyin: Zhēndì) (499-569 CE) was an Indian monk from Ujjain, who is best known for his prolific Chinese translations of Buddhist texts during the Six Dynasties era.[1][2] He is known as one of the four great translators in Chinese Buddhist history (along with Kumārajīva and Xuanzang).[3] He is also known for the various oral commentaries he gave on his translations which were written down by his disciples (and now only survive in fragmentary form).[1] Some of Paramārtha's influential translations include Vasubandhu's Abhidharmakośa, Asaṅga’s Mahāyānasaṃgraha, and Dignāga's Ālambanaparīkṣā & Hastavālaprakaraṇa.[1][4]

Paramārtha is associated with some unique doctrines. He is traditionally seen as having taught the doctrine of the "immaculate consciousness" (amalavijñāna, Ch: amoluoshi 阿摩羅識).[5][6] He is also seen as the source of the doctrine of “original awakening” (benjue [本覺]).[2] Paramārtha is also associated with various works on Buddha-nature that became extremely influential in Chinese Buddhism. These include the Treatise on Buddha Nature (Foxing lun 佛性論) and the Mahayana Awakening of Faith (Dasheng qi xin lun 大乘起信論), a key work for Huayan and Chan Buddhism.[1][2] However, modern scholars have expressed doubts about the attribution of the Awakening of Faith to Paramārtha (as well as numerous other texts), and scholarly opinion remains divided, often due to discrepancies between ancient Chinese catalogs.[2]

Due to his teachings which synthesize Yogacara thought with Buddha-nature ideas, Paramārtha is traditionally seen as a key figure of the Shelun School (攝論宗), a major tradition of Chinese Buddhist thought in the 6th and 7th centuries as well as a major figure of the Faxing school (法性宗, “School of Dharma-nature”).[2] The distinctive doctrine of the Faxing school was "the existence of a pure and transcendent element within the mind, in which case liberation would simply be a matter of recovering that innate purity."[2] This was opposed to the view of Xuanzang and his school, which held that the mind was impure and had to be totally transformed.[2]

Biography

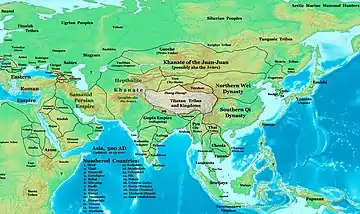

Paramārtha was born in 499 CE in the autonomous kingdom of Malwa in central India, at the end of the Gupta Dynasty.[7] His given name was Kulanātha, meaning "savior of the family", and his parents were Brahmins belonging to the Bhāradvāja clan.[8] His Buddhist name of Paramārtha means "the ultimate meaning," parama: uppermost, artha: meaning. In the Buddhist context, this refers to the absolute, as opposed to merely conventional truth.

Paramārtha became a Buddhist monk in India, most likely in the Sāṃmitīya Vinaya.[2] He received support from royalty for his travels to spread the teachings of Buddhism. He most likely received royal patronage from Bālāditya II or Kumāragupta III.[9] The Maukhari ruler Dhruvasena I may have also supported Paramārtha, as his kingdom was a well-known bastion of the type of Yogācāra teachings advocated by Paramārtha.[9]

The first destination of Paramārtha was the kingdom of Funan, or pre-Angkor Cambodia.[9] Here in Funan, Paramārtha's reputation grew to the extent that Emperor Wu of Liang sent ambassadors to bring Paramārtha to the Chinese imperial court.[10] Paramārtha arrived in China through Guangdong (then called Nanhai) on 25 September 546 CE.23 The conditions of Paramartha's arrival at the capital are described in a Chinese introduction written by Pao Kuei in 597 CE:[10]

During the Ta-t'ung period the emperor sent a rear guard Chang Szu to Funan to send back to China eminent monks and Mahayana sastras and sutras of various kinds. This country [Funan] then yielded in turning over the western Indian Dharma Master from Ujjain, namely Paramartha, who in Liang was called Chen-ti, and many sutras and sastras in order to honor the emperor. After Dharma Master Paramartha had traveled to many kingdoms he had settled in Funan. His manner was lively and intelligent and he relished details in scriptural texts and profound texts, all of which he had studied. In the first year of T'ai-ch'ing (547) he went to the capital and had a visit with the emperor who himself bowed down to him in the Jeweled Cloud quarters of the palace in reverence to him, wishing for him to translate sutras and sastras.

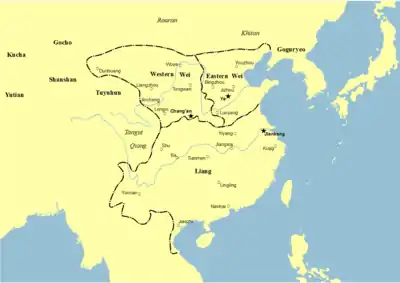

In China, Paramārtha worked with a translation team of twenty accomplished monks.[11] Paramartha's work was interrupted by political events and the general chaotic state of China during this period, which included the murder of Emperor Wu. Several years later, Paramārtha was able to continue translation efforts in earnest with his translation team, beginning with the Golden Light Sutra (Skt. Suvarṇaprabhāsa Sūtra).[12] Despite his success in China, Paramārtha wished to return to India toward the end of his life, but felt that this journey back to the west would be "impossible."[13] Instead, he accepted the patronage of Ouyang Ho and continued his translation efforts at a rapid pace.[13] During much of his later life, Paramārtha continued a pattern of continually translating texts while traveling from region to region in China. He also continued to review his older translations for any areas in which the words and the general meaning were in conflict.[12]

During his later years (562–569) Paramārtha finally attained a stable patronage and could remain in one single place to work - Guangzhou. It was during this late period that he and his main students, like Huikai, Sengzong (僧宗), Fazhun (法准), and Sengren (僧忍), produced the most important translations, like the Abhidharmakośabhāṣya and the Mahāyānasaṃgraha.[2] In this later period, Paramārtha had become famous throughout southern China and had acquired a supportive following of disciples, many of whom traveled great distance to hear his teachings, especially those from the Mahāyānasaṃgraha.[14]

In 569 CE, at the age of 70, he died, and a stūpa was built in his honor.[15]

Teaching

Paramārtha's interest ranged across a wide variety of Buddhist teachings, from Abhidharma, to Yogacara Buddhism, Buddha-nature teaching and Nagarjuna's ethical teachings.[2]

Pure consciousness

However, Paramārtha is most well known for introducing his unique Yogacara doctrine of the "pure consciousness" or "immaculate consciousness" (amalavijñāna, Ch: amoluoshi 阿摩羅識 or wugou shi 無垢識).[5][16][6] This doctrine expands on the Yogacara school's doctrine of eight consciousnesses by introducing the immaculate consciousness as a ninth consciousness.[5][16][6]

The term amalavijñāna was not a new term and had been used by Vasubandhu in his Abhidharmakośa (at 5.29). In this text, the term refers to a “consciousness without outflows” (anăsravavijñăna). This is a consciousness that has been purified of all defilement through insight into the four noble truths and which brings freedom from rebirth.[5] Likewise, the Yogacarabhumi contains teachings on purified consciousness (visuddha vijñāna). It is likely that these earlier sources influenced Paramārtha's conception of immaculate consciousness.[5]

Paramārtha's concept of the amalavijñāna is a pure and permanent (nitya) consciousness that is unaffected by suffering or mental afflictions.[5] This immaculate consciousness is not a basis for the defilements (unlike the ālayavijñāna), but rather is a basis for the noble path (āryamārga).[5] It is thus a purified vijñāna skandha (consciousness aggregate). As Michael Radich notes, Paramārtha holds that there are two different types of basic consciousnesses, "one the basis for worldly and defiled dharmas, and the other the basis of transcendent (lokôttara) dharmas."[5] Furthermore, the phenomena produced by the immaculate consciousness act as the counteragent to all the defilements and the amalavijñāna is said to be attained by the cultivation of the wisdom that knows Thusness (tathatā).[5] According to Paramārtha, Buddhahood is achieved when, after practicing the noble path, the mind experiences the “revolutionary transformation of the basis” (āśrayaparāvṛtti) during which the storehouse consciousness (ālayavijñāna) ceases to exist, leaving only the immaculate consciousness free of all evil (dauṣṭhulya), suffering and all outflows (asrava).[5] Thus, according to Michael Radich "Paramărtha understood *amalavijñăna to be the counteragent to ălayavijñăna, and the two to be in a temporal relationship to one another, whereby ălayavijñăna existed only until liberation, and was then succeeded by fully realised *amalavijñăna."[5]

Some texts attributed to Paramārtha also identify the Yogacara idea of the perfected nature (pariniṣpannasvabhāva) with the amalavijñāna.[5] Some of these texts also see the teaching of the immaculate consciousness as a superior or higher version of the Yogacara doctrine of vijñaptimātra (weishi), which posits not just the unreality of non-mental phenomena, but also the unreality of the defiled consciousness itself.[5]

According to Radich, some sources attributed to Paramārtha also identify the immaculate consciousness with the “innate purity of the mind” (prakṛtiprabhāsvaracitta) and this links the concept with the pure Thusness of the Ratnagotravibhāga and thus with the doctrine of Buddha nature (foxing 佛性). This purity is also linked with the dharmadhātu and, according to Radich, "this is the beginning of a process that links *amalavijñāna into a chain of identifications for (aspects of) the Mahāyāna “absolute”.[5]

Buddha nature

Some modern scholars also consider the "Treatise on Buddha Nature" (Foxing lun 佛性論, T. 1610) to be an original work of Paramārtha, based on his reading of the Ratnagotravibhāga (both texts share many similarities).[17] Because of this, Paramārtha is seen as an important figure in the development of the Yogacara-tathagatagarbha synthesis.[18]

Since the status of the various texts attributed to Paramārtha are still up for debate, attempting to extract Paramārtha's original doctrine from later interpolations and the ideas of other figures in Paramārtha's tradition is quite difficult.[5]

Works

There are many disagreements and discrepancies between the main Chinese Buddhist catalogs regarding Paramārtha's translations and modern scholarly opinion on which works to attribute to him also remain divided.[2] Some scholars have also argued that the term “Paramārtha" should often be regarded not as a single individual, but as a group of scholars, the “Paramārtha group” or translation workshop. This helps explain why the various catalogs diverge in many ways.[2]

According to Keng Ching and Michael Radich, the following key texts are agreed upon by all catalogs (with minor differences in dating etc) as being translations of Paramārtha (and his team of translators):[2]

- Guangyi famen jing (廣義法門經, *Arthavistara-sūtra, T. 97)

- Jin guangming jing (金光明經, Suvarṇabhāsottama-sūtra i.e. Golden Light Sutra)

- Wushang yi jing (無上依經, *Anuttarāśraya-sūtra?, T. 669)

- Jiejie jing (解節經, a part of the Saṃdhinirmocana-sūtra, T. 677).

- Lü ershi’er mingliao lun (律二十二明了論, T. 1461).

- Fo apitan jing chujia xiang pin (佛阿毘曇經出家 相品, T. 1482).

- Apidamo jushe shilun (阿毘達磨俱舍釋論, Abhidharmakośabhāṣya, T. 1559)

- Dasheng weishi lun (大乘唯識論, Viṃśikā, T. 1589).

- She dasheng lun (攝大乘論, Mahāyānasaṃgraha, T. 1593).

- She dasheng lun shi (攝大乘論釋, Mahāyānasaṃgrahabhāṣya of Vasubandhu, T. 1595)

- Zhong bian fenbie lun (中邊分別論, Madhyānta-vibhāga, T. 1599).

- Foxing lun (佛性論, T. 1610), The "Treatise on Buddha Nature", traditionally attributed to Vasubandhu, but this is questioned by modern scholars.[19]

- San wuxing lun (三無性論, T. 1617)

- Rushi lun fan zhinan pin (如實論反質難品, T. 1633).

- Suixiang lun jie shiliu di yi (隨相論解十六諦義, T. 1641).

- Lishi apitan lun (立世阿毘曇論, *Lokasthānābhidharma-śāstra, T. 1644).

- Si di lun (四諦論, T. 1647).

- Baoxing wang zhenglun (寶行王正論, Ratnāvalī of Nagarjuna, T. 1656).

- Posoupandou fashi zhuan (婆藪槃豆法師傳, Biography of the Dharma Master Vasubandhu, T. 2049).

Regarding the famous Mahayana Awakening of Faith (Dasheng qi xin lun 大乘起信論, T. 1666), it is cited as "dubious" in one of the Chinese catalogs, hence the current scholarly debate as to its provenance.[2]

An important source for Paramārtha's doctrine of the immaculate consciousness is the Jueding zang lun (決定藏論, the beginning of the Viniścayasaṃgrahaṇī portion of the Yogācārabhūmi, T. 1584). This text is not included in all catalogs of Paramārtha's works but is considered to be by Paramārtha by various modern scholars including Michael Radich.[2][5]

There are numerous other works attributed to Paramārtha and there is still much scholarly debate regarding which works can be attributed to him.[2]

Scholars have noted that some of Paramārtha's translations contain deviations from their Indic or Tibetan counterparts. Some scholars such as Funayama Tōru have argued that this difference is due to Paramārtha's "lecture notes" being included as part of the translations of the Indian source texts.[2]

Some of Paramārtha's various lost works, including some of his oral commentaries written by his students, have survived in fragmentary form as quotations in later texts. Modern scholars are still working on collecting these fragments.[2]

Influence

After the Paramārtha's death, his various students dispersed and attempted to spread his teachings, but they were not very successful.[2]

It was only due to the efforts of Tanqian (曇遷; 542–607) that Paramārtha's teachings flourished and became popular in the north. In spite of the fact that Tanqian had neither met Paramārtha, nor studied with any of Paramārtha’s students, it was Tanqian who really popularized Paramārtha's teachings, especially the Mahāyānasaṃgrahabhāṣya, which he taught together with the Awakening of Faith. Tanqian is also seen as a key figure of the Shelun School (攝論宗) and he possibly was the main force behind the promotion of the Awakening of Faith as Paramārtha's work.[2] The Shelun School based itself off Paramārtha's translation of Vasubandhu’s Mahāyānasaṃgrahabhāṣya.[20]

As Paramārtha's work became more influential, it also became central to the so called Faxing school (法性宗, “School of Dharma-nature”), which was a Chinese form of Yogacara that also placed much emphasis on the doctrine of tathagatagarbha.[2]

Paramārtha's doctrine of the immaculate consciousness was a particularly influential teaching which was widely adopted by many later Chinese Buddhist thinkers.[5] Beginning with the work of Huijun (慧均, d.u., fl. 574-580s?), the immaculate consciousness began to be widely called the untainted consciousness (wugoushi 無垢識) as well as the “ninth consciousness” (jiushi 九識), an extension of the Yogacara doctrine of eight consciousnesses).[5] While numerous later sources claim that Paramārtha taught the immaculate consciousness as a “ninth consciousness”, this is not found in any of Paramārtha's extant works and Michael Radich writes that the truth of the issue is impossible to determine.[5] Later sources also drew on a passage in the Laṃkâvatăra sūtra to defend the doctrine of immaculate consciousness as a ninth consciousness.[5]

The idea is used by numerous influential East Asian Buddhist authors like Zhiyi (智顗, 538-597), Wŏnch’uk (圓測, 613-696); Wŏnhyo (元曉, 617-686); Amoghavajra (不空金剛, 705-774), Chengguan (澄觀, 738-839); and Zongmi (宗密, 780-841).[5]

Many later authors interpreted Paramārtha's doctrine of the immaculate consciousness through other works, especially the Awakening of Faith. The influence of the Awakening of Faith on the immaculate consciousness doctrine can already be seen in the work of Jingying Huiyuan (淨影慧遠, 523-592). For Huiyuan, the amalavijñăna and the ălayavijñăna are both two aspects of the same "true" consciousness, reminiscent of the "One Mind" of the Awakening of Faith.[5] The doctrine is also further developed in the Vajrasamādhi sūtra.[5]

Faxiang school thinks also commented on the doctrines associated with Paramārtha, the immaculate consciousness and the "ninth consciousness". Kuiji, a key disciple of Xuanzang, saw the doctrine as heterodox and criticized it in his works.[5] Wŏnch’uk meanwhile uses the term untainted consciousness as just a synonym for ālayavijñāna.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Toru Funayama. The work of Paramārtha: An example of Sino-Indian cross-cultural exchange. JIABS 31/1-2 (2008[2010]).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Keng Ching and Michael Radich. "Paramārtha." Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Volume II: Lives, edited by Jonathan A. Silk (editor-in chief), Richard Bowring, Vincent Eltschinger, and Michael Radich, 752-758. Leiden, Brill, 2019.

- ↑ King (1991), p. 21.

- ↑ King (1991), pp. 22-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Radich, Michael. The Doctrine of *Amalavijnana in Paramartha (499-569), and Later Authors to Approximately 800 C.E. Zinbun 41:45-174 (2009) Copy BIBTEX

- 1 2 3 Lusthaus, Dan (1998), Buddhist Philosophy, Chinese. In: Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, p. 84. Taylor & Francis.

- ↑ Paul 1984, p. 14.

- ↑ Paul 1984, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Paul 1984, p. 15.

- 1 2 Paul 1984, p. 23.

- ↑ Paul 1984, p. 25.

- 1 2 Paul 1984, p. 27.

- 1 2 Paul 1984, p. 33.

- ↑ Paul 1984, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Paul 1984, p. 35.

- 1 2 "amalavijñāna - Buddha-Nature". buddhanature.tsadra.org. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ↑ King (1991), p. 23.

- ↑ King (1991), pp. 24-26.

- ↑ King (1991), p. 23.

- ↑ King (1991), p. 23.

Sources

- King, Sallie B. (1991). Buddha Nature. State University of New York Press (SUNY Series in Buddhist Studies).

- Paul, Diana (1984), Philosophy of Mind in Sixth-Century China: Paramartha's Evolution of Consciousness, Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press

Further reading

- Boucher, Daniel, "Paramartha". In: Buswell, Robert E. ed. (2003). Encyclopedia of Buddhism, New York: Macmillan Reference Lib. ISBN 0028657187, pp. 630–631

- Funayama, Toru (2010). The Work of Paramārtha: An Example of Sino-Indian Cross-cultural Exchange, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 31, 1/2, 141 - 183

- Paul, Diana (1982). The Life and Time of Paramārtha (499-569), Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 5 (1), 37-69

- Paul, Diana (1981). The Structure of Consciousness in Paramārtha's Purported Trilogy, Philosophy East and West, 31/3, 297-319 – via JSTOR (subscription required)