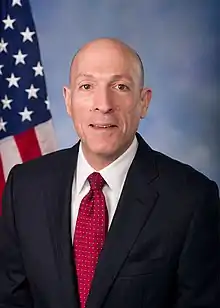

Paul D. Irving | |

|---|---|

| |

| 36th Sergeant at Arms of the United States House of Representatives | |

| In office January 17, 2012 – January 7, 2021 | |

| Leader | John Boehner Paul Ryan Nancy Pelosi |

| Preceded by | Wilson Livingood |

| Succeeded by | Timothy Blodgett |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Paul Douglas Irving August 1957 (age 66) Tampa, Florida, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Jean Parkinson

(m. 1989–2014) |

| Education | American University (BA) Whittier College (J.D.) |

Paul Douglas Irving (born August 1957) is an American former law enforcement officer who served as the Sergeant at Arms of the United States House of Representatives from January 17, 2012, until January 7, 2021, succeeding Wilson Livingood in that post.[1] He resigned due to his inability to fulfill his duty during the 2021 United States Capitol attack.[2][3]

Early life and education

Irving was born in Tampa, Florida in 1957.[4] In 1979, Irving earned a bachelor's degree in justice from American University. In 1982, he earned a J.D. degree from Whittier Law School.[5]

Career

From 1980 to 1983, Irving served as a clerk in the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Los Angeles field office.[6]

In 1983, Irving joined the United States Secret Service,[7] where he served as a supervisory agent in the Presidential Protection Division, as Deputy Assistant Director for Congressional Affairs, and as Assistant Director for Administration.[6]

In 2003, Irving was assigned to the Executive Office of the President at the White House during the Secret Service's transition to the United States Department of Homeland Security.[7] Irving retired from the Secret Service in 2008.[7]

Following his retirement from the Secret Service, Irving became president and managing partner of his family's real estate investment firm, and subsequently joined Command Consulting Group, an international security and intelligence consulting firm, where he was a senior security consultant in the firm's Washington, D.C. headquarters, and managing director of the firm's office in Miami, Florida.[8][9]

On January 17, 2012, Irving was named the House Sergeant at Arms.[9] Irving rose to prominence after the Capitol was attacked on January 6, 2021.

Responding to the 2021 Capitol attack

On January 4, Capitol Police chief Steven Sund requested additional National Guard support from Irving and Senate Sergeant-at-Arms Michael C. Stenger.[10][11] That request was denied. Sund claims Irving's refusal cited concerns about "optics", though Irving disputes this claim.[12][13]

On January 6 at around 1:00 p.m., hundreds of Trump supporters clashed with officers and pushed through barriers along the perimeter of the Capitol.[14][15] The crowd swept past barriers and officers, with some members of the mob spraying officers with chemical agents or hitting them with lead pipes.[16][17] Representative Zoe Lofgren (D–CA), aware that rioters had reached the Capitol steps, was unable to reach Capitol police chief Steven Sund by phone; Irving told Lofgren the doors to the Capitol were locked and "nobody can get in".[18]

At 1:09, Sund called Irving and Stenger and asked them for an emergency declaration required to call in the National Guard; they both told Sund they would "run it up the chain". Irving called back with formal approval an hour later.[19] Irving would later deny the 1:09 p.m. conversation took place, though the call was substantiated by phone records.[20][21]

On January 7, 2021, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced that Irving would be submitting his resignation as Sergeant at Arms.[22] Sund and Stenger also resigned from their posts.[23]

References

- ↑ "Sergeant at Arms | house.gov". United States House of Representatives. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ↑ Griffin, Kyle [@kylegriffin1] (January 7, 2021). "Nancy Pelosi says she has received a resignation notice from the House Sergeant-at-Arms" (Tweet). Retrieved January 12, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ↑ Cochrane, Emily (January 7, 2021). "The House sergeant-at-arms resigns and Schumer says he'll fire the Senate sergeant-at-arms if needed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ↑ "IRVING, Paul | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov.

- ↑ Crockett, Traci (May 14, 2012). "Justice Wonk Serves in Historic Role". American University. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- 1 2 Kim, Seung Min (December 12, 2011). "New House sergeant-at-arms named". POLITICO. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Dumain, Emma (January 17, 2012). "Paul Irving Sworn In as New Sergeant-at-Arms". Roll Call. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ↑ "Speaker Boehner Swears In Paul D. Irving as House Sergeant at Arms-January, 16, 2012 Press Release-Speaker of the House John Boehner". Archived from the original on March 24, 2014. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- 1 2 H.Res. XX — Privileged Resolution Electing the Sergeant-at-Arms of the House of Representatives-The Republican Study Committee Archived 2013-02-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ WALSH, DEIRDRE (January 15, 2021). "Former Capitol Police Chief Steven Sund Defends Agency's Role In Jan. 6 Attack". NPR. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ↑ Beaumont, Peter (January 11, 2021). "Ex-head of Capitol police: officials reluctant to call in national guard". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 13, 2021. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- ↑ "Outgoing Capitol Police chief: House, Senate security officials hamstrung efforts to call in National Guard - The Washington Post". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Cornwell, Susan (February 23, 2021). "U.S. Senate begins review of security failings ahead of deadly Capitol riot". Reuters – via www.reuters.com.

- ↑ Barrett, Ted; Raju, Manu; Nickeas, Peter (January 6, 2021). "Pro-Trump mob storms US Capitol as armed standoff takes place outside House chamber". CNN. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ↑ Lee, Jessica (January 8, 2021). "Did Trump Watch Capitol Riots From a Private Party Nearby?". Snopes. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ↑ Paybarah, Azi; Lewis, Brent (January 7, 2021). "Stunning Images as a Mob Storms the U.S. Capitol". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ↑ Greenberg, Jon; Kim, Noah Y. (January 8, 2021). "Black Lives Matter protests and the Capitol assault: Comparing the police response". PolitiFact. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ↑ Demirjian, Karoun; Leonnig, Carol D.; Kane, Paul; Davis, Aaron C. (January 9, 2021). "Inside the Capitol siege: How barricaded lawmakers and aides sounded urgent pleas for help as police lost control". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 10, 2021. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ↑ Leonnig, Carol D.; Davis, Aaron C.; Hermann, Peter; Demirjian, Karoun (January 10, 2021). "Outgoing Capitol Police chief: House, Senate security officials hamstrung efforts to call in National Guard". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 13, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ↑ Melendez, Pilar (February 25, 2021). "Phone Records Prove House Sergeant-at-Arms DID Ignore Pleas for Backup". The Daily Beast – via www.thedailybeast.com.

- ↑ Perano, Ursula (February 23, 2021). "Former House sergeant at arms denies delay in approving National Guard during riot". Axios.

- ↑ "Pelosi calls for resignation of Capitol Police chief". Washington Post. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ↑ Sund, Steven. "Former Capitol Police Chief Steven Sund Defends Agency's Role In Jan. 6 Attack". NPR.org.