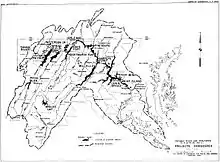

The Potomac River basin reservoir projects were U.S. Army Corps of Engineers programs that sought to regulate the flow of the Potomac River to control flooding, to assure a reliable water supply for Washington, D.C., and to provide recreational opportunities. Beginning in 1921 the Corps studied a variety of proposals for an ambitious program of dam construction on the Potomac and its tributaries, which proposed as many as sixteen major dam and reservoir projects. The most ambitious proposals would have created a nearly continuous chain of reservoirs from tidewater to Cumberland, Maryland. The 1938 program was focused on flood control, on the heels of a major flood in 1936. The reformulated 1963 program focused on water supply and quality, mitigating upstream pollution from sewage and coal mine waste.

While several projects came to fruition in one form or another, most were never pursued or were abandoned after significant public opposition. Savage River was the only project from the 1938 program to be built. The largest project was Seneca Dam on the Potomac just above Washington, D.C.. Seneca was abandoned in 1969 after the creation of Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park, which preserved much of the area Seneca Dam would have flooded. The Verona and Sixes Bridge projects survived into the 1970s. Only the Bloomington project was built approximately as originally proposed, creating Jennings Randolph Reservoir.

In 1968 the landmark study The Nation's River was published by the Department of the Interior, examining strategies for the appropriate use and clean-up of the Potomac. It disputed the strategy of dilution and noted that flood control projects could not be economically justified on their own. The report documented absent or inadequate wastewater treatment, discharge from combined sanitary and stormwater sewers, and agricultural runoff.[1] This document became the basis for Potomac study, development and management.[2] The widespread implementation of pollution controls as a result of the Clean Water Act reduced upstream pollution. Water conservation measures meant that water use did not follow the trend expected by the Corps of Engineers, and reservoirs were not required to meet demand.

Early Potomac development

The river's potential for transportation and hydropower was explored from the beginning of the United States, with George Washington's Potomac Company one of the first consortia to try to exploit the Potomac's route through the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains. The failure of the Potomac Company led to the formation of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal in 1825 to use the river's route to build a still-water canal to Cumberland. Starting in 1799 the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers were used to power the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. A variety of industries grew up in the area, powered by river waters.

The earliest proposals for exploitation of hydropower on the Potomac were made in the 1880s. By the 1920s the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reviewed the possibilities for hydroelectric power at Great Falls.[3] Power generation capacity was planned at 105 MW[4] and total cost was projected at $18,616,000 in 1921.[5]

1938 Corps of Engineers program

As a result of the catastrophic flood of 1936, Congress mandated a study by the Corps of Engineers on flood control on the Potomac. The Corps report published in 1938 proposed a series of dams on the main stem of the Potomac and on several tributaries. The reservoirs were to start at tidewater at Chain Bridge.

Proposed dams on the Potomac included (unbuilt projects in italics):

- Chain Bridge: planned dam to impound the river beginning at tidewater, backing up to Bear Island. Built on a reduced scale in 1959 as Little Falls Dam, about 3 miles (4.8 km) above tidewater. The built version is 14 feet (4.3 m) high and functions as a weir to impound water at the Washington Aqueduct intake.[6][7]

- Bear Island: proposed to create a reservoir extending from the top of the Chain Bridge pool at Bear Island to the base of Great Falls, never built

- Riverbend: proposed at the sharp bend of the Potomac immediately above Great Falls. The 119-foot (36 m) dam would have created a reservoir extending nearly to Harpers Ferry. Superseded by the Seneca Dam proposal farther upriver, also never built.

- Harpers Ferry: Proposed in the vicinity of Sandy Hook and Weverton, the reservoir would have flooded the lower part of Harpers Ferry with a pool extending past Shepherdstown. It was never built.

- Rocky Marsh: Proposed for a site near Scrabble, never built. The site would have been near the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal's Dam No. 4., which survives.

- Pinesburg Proposed for a site near Pinesburg, never built. The site would have been near the historical and present-day Dam No. 5.

- Orleans: Proposed for a site near Little Orleans, never built.[8]

The Shenandoah would have been dammed at two places:

- Millville: The existing small power generation dam at Millville would have been replaced with a much larger structure. Never built. The original 2.84 MW generating station continues to operate.

- Brocks Gap: Like the Riverbend/Seneca Dam project, the Brocks Gap project survived into the 1960s, when it was defeated by local opposition.[8]

Other reservoirs would have included:

- Edes Fort on the Cacapon River. Never built.

- Springfield on the South Branch of the Potomac. Never built.

- Royal Glen on the South Branch, proposed again in 1963. Never built.

- Patterson Creek Never built.

- Keyser on the North Branch of the Potomac. Never built.

With the intervention of World War II none of these projects were pursued, but they were revived in 1945 as a basis for further study.[8]

- Savage River was the only project of the 1938 program to be built as envisioned. The 184-foot (56 m) rockfill dam was completed in 1952.

Potomac River Basin Report

In 1958 the Corps again was directed by Congress to study dams, this time to improve water quality in addition to flood control. Upstream sewage discharge and the effects of coal mine drainage on the Potomac headwaters caused the new focus, in which the assured flow of reservoirs would combine to dilute pollution to an acceptable level for drinking water treatment.[9] A further interest was the creation of recreational opportunities on the new lakes. The new study was published in 1963 as the Potomac River Basin Report. The new plan involved 16 major reservoir projects and 418 small headwater reservoirs. The plan also recommended the use of more effective wastewater treatment strategies. The cost of the entire program was estimated at $498 million in 1963 dollars.[10]

The major projects included (unbuilt projects in italics):

- Seneca above Great Falls on the Potomac. The Seneca proposal was a modification of the Riverbend project, moved about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) upstream. The only one of the 1963 reservoirs proposed for the main stem of the Potomac, it was considered the most potentially useful project, estimated to provide for 50 years of growth in the Washington area.[11] The project was abandoned in the face of extensive opposition in 1969. The 87-foot (27 m) dam was to impound a 38,700-acre (15,700 ha), 1,193,000-acre-foot (1.472 km3) reservoir, at a cost-benefit ratio of 1.6.[12]

- Bloomington on the North Branch of the Potomac. The report proposed a 287-foot (87 m) concrete gravity dam with a gated overflow spillway. The reservoir was to be 1,300 acres (530 ha), impounding 137,000 acre-feet (0.169 km3). The project was completed in 1981 as Jennings Randolph Lake with a rolled earth and rockfill dam, 296 feet (90 m) high. The reservoir area is 952 acres (385 ha). The cost-benefit ratio for the project was projected at 1.7.[13]

- Royal Glen on the South Branch of the Potomac was to provide flood control protection to flood-prone Petersburg, West Virginia,[11] as well as water quality improvement and recreation. The project envisioned a 218-foot (66 m) concrete gravity dam, 700 feet (210 m) wide, and a 5,680-foot (1,730 m) wide earthfill dike. The dam was to have a gated overflow spillway in the concrete section. The reservoir was projected at 3,480-acre (1,410 ha), holding 338,000-acre-foot (0.417 km3). The reservoir was projected to inundate fertile bottomland farms, a stocked trout fishery and whitewater canoeing waters. The reservoir would have inundated the entrance to Smoke Hole Caverns. Despite the damage to existing recreation, the reservoir was projected to increase recreational usage. Cost-benefit ratio was projected at 1.4 without considering recreation. Most of the reservoir would have been within the boundaries of Monongahela National Forest, in an area being considered by the National Park Service for inclusion in Spruce Knob–Seneca Rocks National Recreation Area.[14] The project received extensive opposition and was not supported by the state of West Virginia.[11]

- Chambersburg was to have been located about 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Marion, Pennsylvania, south of Chambersburg on Conococheague Creek. The project envisioned a 79-foot (24 m) high concrete gravity dam section in an earth dike, 2,730 feet (830 m) long. The spillway was to be a gated overflow in the concrete section, with a piped sluice section for low flows. The project would have required the construction of an interceptor sewer to divert upstream effluent around the reservoir, returning it to the Conococheague below the dam. The reservoir was to have covered 1,570 acres (640 ha), storing 42,800 acre-feet (0.0528 km3). 75 families were to be displaced, and 500 acres (200 ha) of farmland were to have been inundated, along with 900 acres (360 ha) of pasture. The displacement was justified by property enhancement to adjoining lands. The cost-benefit ratio was set at 1.9 (1.7 without recreation), for an overall cost in 1963 of $12,406,000.[14]

- Staunton, later Verona was proposed on the Middle River of the South Fork of the Shenandoah. The project site was to have been 4.6 miles (7.4 km) east of Verona, Virginia, about 9 miles (14 km) from Staunton. The majority of the dam was to be earthfill, with a 97-foot (30 m) high concrete gravity overflow section impounding a 4,750-acre (1,920 ha) 143,000-acre-foot (0.176 km3) reservoir. Impact on farming was judged to be "relatively severe," with 64 farms, 19 part-time farms and 22 residences affected by the impoundment. 50 families would have had to be relocated. An interceptor sewer was needed to divert effluent from Staunton and Verona to a point below the dam where flow was judged to be sufficient to handle the effluent. The cost-benefit ratio was set at 2.3, at a project cost of $24,086,000 in 1963 dollars.[15] The Verona project survived longer than most of the 1963 proposals and was authorized to proceed under the Water Resources Development Act of 1974.[16] A 1966 referendum in Augusta County favored the project.[11] Later the project encountered intense opposition from surrounding landowners and was opposed by Virginia Governor John N. Dalton.[17][18] Although the proposal survived into the 1970s funding was blocked by Congress in 1977.[19]

- Sixes Bridge (or Six Bridge as originally proposed) was planned for the upper Monocacy River in northern Frederick County, Maryland. The 73-foot (22 m) high dam was to impound a 4,650-acre (1,880 ha) reservoir of 103,000 acre-feet (0.127 km3). An earthfill dam totaling 2,240 feet (680 m) in length was proposed with a center concrete gravity overflow section. The 12-mile (19 km) reservoir was to extend about 3 miles (4.8 km) into Pennsylvania. The project narrative describes the area as one of the most productive farming areas in the Potomac Basin, with project impact described as "rather severe." 70 families were to be displaced. The National Park Service endorsed the project for its recreational potential. Cost in 1963 dollars was $14,374,000. The cost-benefit ratio was projected at 1.3 without recreation and 1.6 including recreation.[20] The project was de-authorized in 1981 by Public Law 97-128.[21]

- West Branch on the West Branch of Conococheague Creek was to be a 95-foot (29 m) earthfill dam on the west branch of Conococheague Creek, about 11 miles (18 km) north of Mercersburg, Pennsylvania. The reservoir as planned at 2,500 acres (1,000 ha) with a capacity of 77,500 acre-feet (0.0956 km3). The reservoir would have flooded the town of Metal, displacing 70 families. The proposed project also created difficulties for the local school district's ability to repay a bond debt. Although the proposal acknowledged the project's limited contribution to water resources, it still computed a cost ratio of 1.6 without recreation and 1.8 including recreation.[22]

- Brocks Gap was proposed for the North Fork of the Shenandoah River just upstream from Cootes Store across Brocks Gap in Little North Mountain. The earthfill dam was to be 147 feet (45 m) high with a 3,870-acre (1,570 ha) reservoir of 187,200 acre-feet (0.2309 km3). The reservoir would flooded the village of Fulks Run. Cost in 1963 dollars was set at $16,437,000. The benefit-to-cost ratio was set at 2.6.[23] The project encountered intense local opposition as well as from Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd and was withdrawn in 1967.[24]

- Winchester, was proposed as an 80-foot (24 m) earthfill dam on Opequon Creek near Winchester, Virginia. It was to have a 2,350-acre (950 ha) reservoir with a capacity of 77,000 acre-feet (0.095 km3).15 farms and 35 families would have been displaced. An interceptor sewer was required to divert sewage from Winchester around the reservoir. Cost was estimated at $10,979,000 in 1963 dollars, with a cost-benefit ration set at 1.4 without recreation, and 1.7 with recreation.[25]

- Licking Creek was proposed at the Maryland-Pennsylvania border on Licking Creek, about 19 miles (31 km) west-northwest of Hagerstown, Maryland. The earthfill dam was to be 148 feet (45 m) high. The reservoir was to cover 2,200 acres (890 ha) with a capacity of 120,500 acre-feet (0.1486 km3). Normal-flow water releases were to be regulated by an intake tower that would allow selection of temperature and oxygenation depending on the level selected. 35 families were expected to be displaced. The cost-benefit ratio was estimated at 1.2 without recreation and 1.8 with recreation, at a 1963 cost of $11,301,000.[26]

- Mount Storm on the Stony River. The project was to be built just west of Mount Storm, West Virginia, below Mount Storm Lake, completed in 1965, which was privately constructed to provide cooling water for the Mount Storm Power Station. A 154-foot (47 m) earthfill dam was proposed with an overflow spillway and outlet works for future power development in the east abutment. The project would have impounded 43,500 acre-feet (0.0537 km3) in a 770-acre (310 ha) pool. Although the project is described in the 1963 report as essential to maintain the quality of the Stony River, the report makes no mention of the much larger Mount Storm Lake, under construction immediately upstream. No residents or businesses would have been displaced, though coal mining in the immediate area of the reservoir would have been curtailed.1963 project cost was estimated at $9,762,000. Cost-benefit ratio was projected to be 1.8.[27]

- Town Creek near Oldtown, Maryland on Town Creek. A 127-foot (39 m) earthfill dam was proposed to impound a 2,190-acre (890 ha) reservoir with a capacity of 96,800 acre-feet (0.1194 km3) at a cost of $9,762,000, the same cost as the Mount Storm project. An outlet/diversion tunnel was to run under the dam, fed by an intake tower. An overflow spillway would have been built in a dike to the west of the dam, discharging across a meander. The project was expected to inundate farmland and woodland. 70 families, a church, a store and a garage would have been displaced. The cost-benefit ration was termed "marginal" at 1.07.[28]

- North Mountain was proposed for Back Creek (Potomac River) in West Virginia near Glengary. The 11-mile (18 km) reservoir was projected to extend 2 miles (3.2 km) into Virginia, covering 5,370 acres (2,170 ha) with 195,000 acre-feet (0.241 km3) of storage. The large lake was expected to provide significant recreation opportunities. The dam was proposed as an earthfill structure, 99 feet (30 m) high, with a broad overflow spillway in the east abutment. The outlet was planned as a tower that could release water from varying depths to control temperature and oxygen content. 55 families, two schools and two cemeteries were to be relocated, with 4,300 acres (1,700 ha) of farmland inundated. The cost-benefit ratio was projected to be 1.6.[29]

- Savage II was planned on the Savage River above the earlier Savage River Reservoir. The 213-foot (65 m) dam was to impound 50,000 acre-feet (0.062 km3) in a 580-acre (230 ha) lake. Ten families would have been displaced and bout 300 acres (120 ha) of farmland would have been inundated. Cost-benefit ration was calculated at 1.7, largely on the basis of the potential project's prospects for "excellent fishing." The earthfill dam was to have an overflow spillway at the west abutment, with an adjoining outlet tunnel fed by an intake tower.[30]

- Back Creek on Back Creek in Pennsylvania was planned to improve water quality on Conococheague Creek. A 68-foot (21 m) concrete gravity dam was proposed, with a 1,990-acre (810 ha) reservoir retaining 46,900 acre-feet (0.0579 km3). Cost was estimated at $7,329,000 in 1963 dollars, with a cost-benefit ratio of 2.2, or 1.7 if recreation was not considered. The project was opposed by local interests. 40 families would have been displaced and 1,500 acres (610 ha) of farmland would have been affected.[31]

- Tonoloway Creek was planned for Tonoloway Creek near Hancock, Maryland. The earthfill dam was to be 127 feet (39 m) high with a reservoir extending 7 miles (11 km) into Pennsylvania. The reservoir was to extend over 2,260 acres (910 ha) with 88,000 acre-feet (0.109 km3) of storage. 20 families were expected to be displaced. 1963 costs were expected to be $13,816,000 and the cost-benefit ratio was calculated to be 1.3.[32]

Of all of these projects, only Bloomington was constructed.

References

- ↑ "II: The Cleansing of the Waters". The Nation's River. U.S. Department of the Interior. October 1, 1968.

- ↑ Jaworski, Norbert; Romano, Bill; Buchanan, Claire (2007). "CH. 1: Introduction". The Potomac River Basin and its Estuary: Landscape Loadings and Water Quality Trends 1895-2005 (PDF).

- ↑ Tyler, M.C. (February 14, 1921). Development of Great Falls for Water Power and Increase of Water Supply for the District of Columbia. Government Printing Office. p. 110.

- ↑ Corps of Engineers 1921, p. 49

- ↑ Corps of Engineers 1921, p. 50

- ↑ Seltzer, Yosefi (October 13, 1994). "Environmentalists Push for Overhaul of Little Falls Dam". Washington Post. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ↑ Peck, Garrett (2012). The Potomac River: A History and Guide. The History Press. ISBN 978-1609496005.

- 1 2 3 Mackintosh, Barry (1991). "4: The Parkway Proposition". Chesapeake and Ohio Canal: The Making of a Park. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Vol. 1 - Report". Potomac River Basin Report. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. February 1963. pp. 92–94. hdl:2027/uiug.30112060272249.

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 1, pp. 21-28

- 1 2 3 4 "II: Toward a More Useful River". The Nation's River. U.S. Department of the Interior. October 1, 1968.

- ↑ "Vol. 2 - Major Reservoir Project Descriptions". Potomac River Basin Report. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. February 1963. pp. 75–85. hdl:2027/uiug.30112060272249.

- ↑ "Jennings Randolph Lake". Army Corps of Engineers Baltimore District. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- 1 2 USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 15-26

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 39-50

- ↑ Public Law 93-251, Water Resources Development Act of 1974

- ↑ "Dalton: Pump water from Shenandoah". Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star. AP. September 9, 1977. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ Rosenfeld, Megan; McAllister, Bill (September 9, 1977). "Dalton Plan Would Give Area Water". Washington Post.

- ↑ "Funding for dam temporarily blocked". Fredericksburg Free Lance-Star. AP. May 7, 1977.

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 51-61

- ↑ "Public Law 97-128" (PDF). Government Printing Office.

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 63-73

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 75-85

- ↑ "Byrd Statement On Proposed Dams". Charles Town Farmers Advocate. March 30, 1945. p. 6.

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 87-97

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 113-123

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 125-133

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 135-143

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 147-157

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 159-167

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 169-178

- ↑ USACE 1963, Vol. 2, pp. 179-189