Pro Cluentio is a speech by the Roman orator Cicero given in defense of a man named Aulus Cluentius Habitus Minor.

Cluentius, from Larinum in Samnium, was accused in 69 BC by his mother Sassia of having poisoned his stepfather, Statius Abbius Oppianicus. Cluentius had prosecuted Oppianicus successfully in 74 BC for attempting to poison him, securing Oppianicus' exile.[1] Both sides in the lawsuit were accused of bribing the jurors during the trial to secure conviction of one another, but only Oppianicus' bribe was revealed at the time. Oppianicus died in disgrace three years later, leaving his widow Sassia to plot revenge against her son. Cicero divides his action in two parts: in the first one, he defends Cluentius' reputation. He shows that Oppianicus' crimes were so enormous, that Cluentius had no need of corrupting the judges; actually, he ridicules Oppianicus because he was cheated by a mediator in bribes. The second part deals with the alleged poisoning, and is very brief, since Cicero considers the accusation as ludicrous.

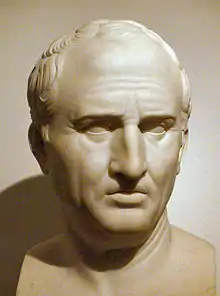

Oppianicus

Statius Albius Oppianicus came from one of Larinum's most prominent families, the Oppianici; he was married five different times throughout his life and was widely suspected of poisoning his first wife Cluentia. Through his son Oppianicus the Younger, the issue of Oppianicus' second marriage to Magia Auria, Oppianicus senior plotted to obtain the fortune of his mother-in-law Dinaea. Oppianicus the Younger was the heir-presumptive to Dinaea's estate, recently enlarged after the deaths of two of her sons, Gnaeus Magius and Numerius Aurius, in the Civil Wars between Marius and Sulla. However, it was discovered that her presumed-dead third son, M. Aurius, was in fact alive and living in servitude in the Ager Gallicus. Oppianicus arranged for the murder of Dinaea and sent an assassin to kill M. Aurius before he could be rescued by family members. He then altered Dinaea's will, which had left only a portion of her estate to her grandson, making Oppianicus the Younger the sole inheritor.[2]

When the news of M. Aurius's death in Gaul reached Larinum, the relatives of Dinaea raised such an outcry that Oppianicus fled the town and took refuge in one of Sulla's camps. Through the favor he enjoyed with Sulla, Oppianicus had his Aurii accusers proscribed; he returned to the town with martial powers and killed his enemies. The paternal aunt of Cluentius was Oppianicus's ex-wife; Oppianicus killed her and, with the same poison, his own brother. His brother's wife was pregnant; Oppianicus poisoned her before she gave birth to the baby, and inherited. Cn. Magius, Oppianicus' brother-in-law, died; in his will, he left everything to his yet unborn son. Oppianicus, who was next in the line of succession, paid Magius' wife a large sum, and she aborted her pregnancy. He then married her, although the marriage did not last long. Then he went to Rome, became intimate with a young dissolute, Asuvius, and killed him after he had signed a will in his favor.

In 80 BC, Oppianicus fell in love with Sassia, the widow of his former brother-in-law, Aulus Cluentius Habitus the Elder. Cluentius the Elder had fallen victim to the Sullan proscriptions and the widowed Sassia then fell in love with her son-in-law Melinus and forced her daughter to divorce him so that she could marry him herself. Oppianicus arranged for Melinus's murder so that Sassia could be free to marry him; she was disinclined, however, to be a stepmother, so Oppianicus obligingly murdered his two youngest sons before she agreed to the marriage.[3]

Aftermath

Cicero was so successful that the young Cluentius was absolved of the charges. In the process the reputation of Sassia was completely destroyed. According to Quintilian, Cicero afterwards boasted that he had pulled the wool over the judges' eyes (se tenebras offudisse iudicibus in causa Cluenti gloriatus est, Institutio Oratoria 2.17.21; the context is in discussion of orators who say false things not because they are themselves unaware of the truth, but to deceive other people).

Cicero's spirited defence in Pro Cluentio presents an insight into the life in Larinum in 66 BC, and also provides an image of a ruthless woman which has lasted for more than two thousand years.

References

External links

Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: Pro Aulo Cluentio Habito

Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: Pro Aulo Cluentio Habito- Cicero, Pro Cluentio, English translation at attalus.org