| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

|

|

Protestant liturgy or Evangelical liturgy is a pattern for worship used (whether recommended or prescribed) by a Protestant congregation or denomination on a regular basis. The term liturgy comes from Greek and means "public work". Liturgy is especially important in the Historical Protestant churches, both mainline and evangelical, while Baptist, Pentecostal, and nondenominational churches tend to be very flexible and in some cases have no liturgy at all. It often but not exclusively occurs on Sunday.[1][2]

Types

Communion liturgies

Lutherans have retained and utilized much of the Roman Catholic mass since the early modifications by Martin Luther. The general order of the mass and many of the various aspects remain similar between the two traditions. Latin titles for the sections, psalms, and days have been widely retained, but more recent reforms have omitted this. Recently, Lutherans have adapted much of their revised mass to coincide with the reforms and language changes brought about by post-Vatican II changes.[3]

Protestant traditions vary in their liturgies or "orders of worship" (as they are commonly called). Other traditions in the west often called "Mainline" have benefited from the Liturgical Movement which flowered in the mid/late 20th century. Over the course of the past several decades, these Protestant traditions have developed remarkably similar patterns of liturgy, drawing from ancient sources as the paradigm for developing proper liturgical expressions. Of great importance to these traditions has been a recovery of a unified pattern of Word and Sacrament in Lord's Day liturgy.[4]

Many other Protestant Christian traditions (such as the Pentecostal/Charismatics, Assembly of God, and Non-denominational churches), while often following a fixed "order of worship", tend to have liturgical practices that differ from that of the broader Christian tradition.[5]

Divine office

The term "Divine Office" describes the practice of "marking the hours of each day and sanctifying the day with prayer".[6]

In Lutheranism, the offices were also combined into the two offices of Matins and Vespers, both of which are still maintained in modern Lutheran prayer books and hymnals. A common practice among Lutherans in America is to pray these offices mid-week during Advent and Lent. The office of Compline is also found in some Lutheran worship books and more typically used in monasteries and seminaries (cf. The Brotherhood Prayer Book).

In Anglican churches, as with Lutheranism, the offices were combined into two offices: Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, the latter sometimes known as Evensong. In more recent years, the Anglicans have added the offices of Noonday and Compline to Morning and Evening Prayer as part of the Book of Common Prayer. The Anglican Breviary, containing 8 full offices, is not the official liturgy of the Anglican Church.

Rites

Protestant liturgy and ritual families are primarily influenced by the theological development of the regions.[7]

Western rites

| Extant |

|---|

|

Eastern rites

| Extant |

|---|

|

Liturgical rites by denomination

Different Christian traditions have employed different rites:

Historical Protestantism

Lutheranism

In the parts of North American Lutheranism that use it, the term "Divine Service" supplants more usual English-speaking Lutheran names for the Mass: "The Service" or "The Holy Communion." The term is a calque of the German word Gottesdienst (literally "God-service" or "service of God"), the standard German word for worship.

As in the English phrase "service of God," the genitive in "Gottesdienst" is arguably ambiguous. It can be read as an objective genitive (service rendered to God) or a subjective genitive (God's "service" to people). While the objective genitive is etymologically more plausible, Lutheran writers frequently highlight the ambiguity and emphasize the subjective genitive.[8] This is felt to reflect the belief, based on Lutheran doctrine regarding justification, that the main actor in the Divine Service is God himself and not man, and that in the most important aspect of evangelical worship God is the subject and we are the objects: that the Word and Sacrament are gifts that God gives to his people in their worship.

Although the term Mass was used by early Lutherans (the Augsburg Confession states that "we do not abolish the Mass but religiously keep and defend it"[9]) and Luther's two chief orders of worship are entitled "Formula Missae" and "Deutsche Messe"—such use has decreased in English usage except among Evangelical Catholics and "High Church Lutherans". Also, Lutherans have historically used the terms "Gottesdienst" or "The Service" to distinguish their Service from the worship of other protestants, which has been viewed as focusing more on the faithful bringing praise and thanksgiving to God.[10]

Various forms of the liturgy are used by Lutherans:

- Latin Liturgy of Martin Luther, a form of Pre-Tridentine Mass, based on Formula missae, used mostly in Evangelical Catholic Lutheran and some high church Lutheran churches

- Byzantine rite or known as Divine Liturgy, used by eastern Lutheranism

- German Liturgy of Martin Luther or Deutsche Messe, mostly in western Lutheranism, known as Divine Service among Conservative Lutherans and Holy Communion or The Eucharist among progressive Lutherans

Reformed

The origins of the liturgy are in John Calvin's Geneva, which became the model for all continental Reformed worship, and by the end of the sixteenth century a fixed liturgy was being used by all Reformed churches.[11] Dutch Reformed churches developed an order of worship in refugee churches in England and Germany which was ratified at synods in Dordrecht in 1574 and 1578. The form emphasizes self-examination between the words of institution and communion consisting of accepting the misery of one's sin, assurance of mercy, and turning away those who are unrepentant.[12] Calvin did not insist on having explicit biblical precedents for every element of worship, but looked to the early church as his model and retained whatever he considered edifying.[13] The liturgy was entirely in the vernacular, and the people were to participate in the prayers.[14]

- John Calvin's Order of Worship, or known as Geneva liturgy, based on Regulative principle of worship, used mostly in Calvinism and some presbyterian churches

- John Knox's Liturgy, based on Book of Common Order, used mostly in Presbyterianism, especially in the Church of Scotland.

Anglicanism

At the time of English Reformation, the Sarum Rite was in use along with the Roman Rite. Reformers in England wanted the Latin mass translated into the English language. Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer authored the Exhortation and Litany in 1544. This was the earliest English-language service book of the Church of England, and the only English-language service to be finished within the lifetime of King Henry VIII.[15] In 1549, Cranmer produced a complete English-language liturgy. Cranmer was largely responsible for the first two editions of the Book of Common Prayer. The first edition was predominantly pre-Reformation in its outlook. The communion service, lectionary, and collects in the liturgy were translations based on the Sarum Rite[16] as practised in Salisbury Cathedral.

The revised edition in 1552 sought to assert a more clearly Protestant liturgy after problems arose from conservative interpretation of the mass on the one hand, and a critique by Martin Bucer on the other. Successive revisions are based on this edition, though important alterations appeared in 1604 and 1662. The 1662 edition is still authoritative in the Church of England and has served as the basis for many of the Books of Common Prayer of national Anglican churches around the world. Those deriving from Scottish Episcopal descent, such as the Prayer Books of the American Episcopal Church, have a slightly different liturgical pedigree.

- Anglican tradition, also known as Anglican rite, based on Book of Common Prayer

- Exhortation and Litany (1544), Protestant predecessor of the Book of Common Prayer

Methodism

The United Methodist liturgical tradition is based on The Sunday Service of the Methodists, which was passed along to Methodists by John Wesley (an Anglican priest who led the early Methodist revival) who wrote that

there is no Liturgy in the world, either in ancient or modern language, which breathes more of a solid, scriptural, rational piety, than the Common Prayer of the Church of England.[17]

When the Methodists in America were separated from the Church of England, John Wesley himself provided a revised version of the Book of Common Prayer called The Sunday Service of the Methodists. Wesley's Sunday Service has shaped the official liturgies of the Methodists ever since. Worship, hymnology, devotional and liturgical practices in Methodism were also influenced by Lutheran Pietism and, in turn, Methodist worship became influential in the Holiness movement.[18]

The United Methodist Church (the largest Methodist denomination) has official liturgies for services of Holy Communion, baptism, weddings, funerals, ordination, anointing of the sick for healing, and daily office "praise and prayer" services. Along with these, there are also special services for holy days such as All Saints Day, Ash Wednesday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Easter Vigil. All of these liturgies and services are contained in The United Methodist Hymnal and The United Methodist Book of Worship (1992).[19] In most cases, congregations also use other elements of liturgical worship, such as candles, vestments, paraments, banners, and liturgical art.

- Traditional Methodist use, also known as Wesleyan Liturgy, based on The Sunday Service of the Methodists

- Methodist use of 1965, the second liturgical use, based on Book of Worship for Church and Home (1965), was always considered optional and completely voluntary

- United Methodist use, based on The United Methodist Book of Worship

Because John Wesley advocated outdoor evangelism, revival services are a traditional worship practice of Methodism that are often held in local churches, as well as at outdoor camp meetings, brush arbour revivals, and at tent revivals.[20][21][22]

Eastern Protestantism

Byzantine tradition (Eastern European)

- Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom, used by eastern orthodox churches which accepted the reformation, such as the Evangelical Church of Romania, Evangelical Orthodox Church, and Ukrainian Lutheran Church

Antiochian tradition

- Liturgy of Saint James, West Syriac Rite, used by the Mar Thoma Syrian Church, St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India, and Assyrian Evangelical Church

- Revised Common Lectionary, used by the Believers Eastern Church

Alexandrian tradition

- Liturgy of St. Dioscorus, Ethiopic Rite, principally used by P'ent'ay congregations

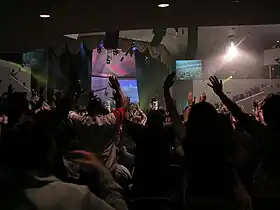

Pentecostalism and nondenominational Christianity

Worship service

The worship service in neo-charismatic and Pentecostal churches is seen as facilitating "the beleivers' encounter with God."[23][24] Certain churches in the Pentecostal tradition are more informal in their worship, while others, such as the Church of God, use a formal liturgy.[25] It is usually run by a pastor and contains two main parts, the praise (Christian music) and the sermon, with periodically the Lord's Supper.[26][27] During worship there is usually a nursery for babies.[28] Children and young people receive an adapted education, Sunday school, often before the service of worship.[29]

- Pentecostal and Charismatic services

While most Holiness Pentecostal churches use the Methodist rite, other Pentecostal movements, such as charismatic movement use a new conception of praise in worship, such as clapping and raising hands as a sign of worship, it also takes place in many non-charistmatic evangelical denominations.[30]

In the 1980s and 1990s, contemporary Christian music, including a wide variety of musical styles, such as Christian rock and Christian hip hop, appeared in the praise.[31][32][33]

References

- ↑ HKT (2021-10-16). "Protestantism". HKT Consultant. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ Bjorlin, David (2018-06-21). "Hope of the World": the liturgical work and witness of Georgia Harkness".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Luther's Reform of the Mass". Lutheran Reformation. 2017-03-27. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ slife (2020-05-20). "Christian Liturgy". The Spiritual Life. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ slife (2020-05-20). "Christian Liturgy". The Spiritual Life. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ Fernand Cabrol, "Divine Office" in Catholic Encyclopedia (New York 1911)

- ↑ "Evangelical church | Definition, History, Beliefs, Key Figures, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ See, e.g., John T. Pless, "Six Theses on Liturgy and Evangelism," Archived December 23, 2005, at the Wayback Machine (Conference on Liturgy and Outreach, Concordia College, 1987) ("[I]n worship God is at work to serve His people with His Word and Sacraments. Evangelical worship is Gottesdienst (subjective genitive), Divine service.").

- ↑ Article 24 of the Augsburg Confession

- ↑

- ↑ White 1989, p. 68–69.

- ↑ Bürki 2003, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ White 1989, p. 67.

- ↑ White 1989, p. 63.

- ↑ F Procter & W. H. Frere, A New History of the Book of Common Prayer (Macmillan, 1905) p. 31.

- ↑ Bevan, G. M. (1908). Portraits of the Archbishops of Canterbury. London: Mowbray.

- ↑ Works of John Wesley, vol. XVI, page 304

- ↑ Ruth, Lester (2009). "Worship: Sacraments, Liturgy, Hymnody, Preaching – Liturgical Revolutions". In Kirby, James E.; Abraham, William J. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Methodist Studies. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 324–329. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199696116.013.0018. ISBN 9780199696116. LCCN 2009926748. S2CID 152440716.

- ↑ 2008 Book of Discipline paragraph 1114.3

- ↑ Winn, Christian T. Collins (2007). From the Margins: A Celebration of the Theological Work of Donald W. Dayton. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 115. ISBN 9781630878320.

In addition to these separate denominational groupings, one needs to give attention to the large pockets of the Holiness movement that have remained within the United Methodist Church. The most influential of these would be the circles dominated by Asbury College and Asbury Theological Seminary (both in Wilmore, KY), but one could speak of other colleges, innumerable local campmeetings, the vestiges of various local Holiness associations, independent Holiness oriented missionary societies and the like that have had great impact within United Methodism. A similar pattern would exist in England with the role of Cliff College within Methodism in that context.

- ↑ Dresser, Thomas (4 May 2015). Martha's Vineyard: A History. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. p. 57. ISBN 9781625849045.

- ↑ Chilcote, Paul W.; Warner, Laceye C. (13 February 2008). The Study of Evangelism: Exploring a Missional Practice of the Church. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 206. ISBN 9780802803917.

- ↑ Braun, Gabriele G. (19 June 2020). God's Praise and God's Presence: A Biblical-Theological Study. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-1-5326-5506-7.

- ↑ Gerald R. McDermott, The Oxford Handbook of Evangelical Theology, Oxford University Press, UK, 2013, p. 311

- ↑ Vaughan, Benson (23 March 2018). The Influence of Music on the Development of the Church of God (Cleveland, Tennessee). Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-5326-3334-8.

Some have claimed Pentecostals still have no liturgy of their own; however, this study clearly established that the Church of God has a liturgy that has been constantly developing throughout the past 125 years.

- ↑ Cartledge, Mark J.; Swoboda, A. J. (7 July 2016). Scripting Pentecost: A Study of Pentecostals, Worship and Liturgy. Routledge. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-317-05866-3.

The 1911 Constitution and General Rules of the Pentecostal Holiness Church contains a rubric for celebrating the Lord's Supper. It directs the pastor, "at the close of the sermon or Scripture lesson, or at any time that may be deemed proper," to call the deacons to "gather round the table and kneel with the whole congregation" in preparation for the rite.

- ↑ Stewart, Adam (30 September 2015). The New Canadian Pentecostals. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-77112-141-5.

The service begins with the worship leader and worship team playing a high-energy song intended to signal the transition from this informal greeting time to the worship component of the service. ... After another three or four songs come the announcements and the collection or offering, which are both usually directed by the senior pastor of the congregation. The offering is followed by one or two more subdued worship songs, intended to prepare the worshipers for the sermon. Occasionally, however, the assistant pastor or lay leader within the congregation preaches instead. If it happens to be the first Sunday of the month, the congregation will celebrate communion, which usually follows the sermon, the senior pastor officiating with the assistance of lay leaders.

- ↑ Greg Dickinson, Suburban Dreams: Imagining and Building the Good Life, University of Alabama Press, USA, 2015, p. 144

- ↑ Lang, J. Stephen (10 September 1999). 1,001 Things You Always Wanted to Know About the Holy Spirit. Thomas Nelson. ISBN 978-1-4185-6857-3.

- ↑ Robert H. Krapohl, Charles H. Lippy, The Evangelicals: A Historical, Thematic, and Biographical Guide, Greenwood Publishing Group, USA, 1999, p. 171

- ↑ Suzel Ana Reily, Jonathan M. Dueck, The Oxford Handbook of Music and World Christianities, Oxford University Press, USA, 2016, p. 443

- ↑ Mathew Guest, Evangelical Identity and Contemporary Culture: A Congregational Study in Innovation, Wipf and Stock Publishers, USA, 2007, p. 42

- ↑ Don Cusic, Encyclopedia of Contemporary Christian Music: Pop, Rock, and Worship: Pop, Rock, and Worship, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2009, p. 85-86