| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Afghanistan |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Sport |

Across Afghanistan, proverbs are a valued part of speaking, both publicly and in conversations. Afghans "use proverbs in their daily conversations far more than Westerners do, and with greater effect".[1] The most extensive proverb collections in Afghan languages are in Pashto and Dari, the two official languages in Afghanistan.

Pashto is the native tongue of Afghanistan's largest ethnic group, the Pashtuns, who are also the second biggest ethnic group in Pakistan. Pashto has the oldest and largest collections of proverbs. The Dari, which is a variety of Persian spoken in Iran and Tajikistan. A broader, more contextualized, study of Afghan proverbs would include comparisons of Afghan proverbs with Persian proverbs from Iran (for which several volumes are available in English) and with Tajik proverbs (e.g. comparing with those in Bell 2009) from Tajikistan.

Collections

So far, collections of proverbs in Afghan languages are available in English translation for at least four Afghan languages: Dari, Pashto, Pashai, and Balochi. Collections of Pashto, Dari, and Balochi proverbs in Arabic script are downloadable at the links at bottom of this article.

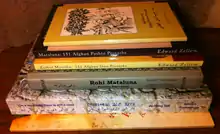

Dari: For Dari, there are two main published collections of proverbs, with some overlap between them. The earlier is J. Christy Wilson's collection of 100 (2002), One Hundred Afghan Persian Proverbs, the list having been reproduced (without credit) in other sources.[2][3] The most recent main collection of Dari proverbs is the 3rd edition of U.S. Navy Captain Edward Zellem's collection, built on the 151 of the 2012 edition, plus 50 more that were submitted via the Web.[4][5] The 2012 edition won a 2013 award from the Military Writers Society of America.[6] From the 151 proverbs of the 2012 edition, 38 were chosen for an edition with color illustrations, intended for language learning by a more popular audience (Zellem 2012a). This edition's format has been published with translations into a number of languages, including English, Russian (Zellem 2013a), German (Zellem 2013b), French (2013c), and Finnish. There are reports that Zarbolmathalhâ, a collection of 1,152 Dari proverbs collected by Mowlânâ Khâl Mohammad Khaste, was published in 1983 (Kreyenbroek 2010:317). There is also a collection of Dari proverbs with German translations by Noor Nazrabi, Afghanische Redensarten und Volksweisheiten.[7]

Pashto: For Pashto, one of the two main languages of Afghanistan, the newest available source is the collection of 151 proverbs by Zellem.[8][9] A larger collection of Pashto proverbs of 1,350 proverbs is by Bartlotti and Khattak (2006), a revised and expanded version of an earlier work by Tair and Edwards (1982). Enevoldsen published 100 proverbs and 100 tapas folk poems (1967). An earlier collection was published by Benawa (1979). An older source containing 406 Pashto proverbs is Thorburn's Bannú: Or Our Afghan Frontier (1876), where he includes them in his book on pp. 231–473. Another out-of-print collection is Boyle's "Naqluna": Some Pushtu Proverbs and Sayings from 1926. The most recent published collection of Pashto proverbs contains 151 proverbs submitted by Pashto speakers via the Web and Twitter (Zellem 2014). There are reports that Nuri published a selection of proverbs from Paśto Toləna in 1910 (Kreyenbroek 2010:151). There are about 50 pages of Pashto proverbs arranged by topic in a doctoral dissertation by Bartlotti.[10] Three additional volumes on Pashto proverbs have also been published in Pakistan, the first by M.M.K. Shinwari, Da mataluno qisay (stories of proverbs) in 1999.[11] There are two additional volumes printed in Pakistan, both by M. A. Lashkar, Oulasi mataluna (Popular proverbs) in 2005[12] and Da mataluno qisay: Ter pa her baqi rozgar (Stories of proverbs: Old forgotten new adopted) in 2009.[13] There is also a collection of proverbs prepared by Boyle in 1926.[14] Noor Sanauddin, a Pashto proverb scholar, has compared all available collections of Pashto proverbs.[15] Farid and Dinakhel have described the impact of proverbs that address the role of women.[16]

Pashai: Pashai is a less known language community living east of Kabul. A local committee working with Yun produced a collection of 171 proverbs (2010), each one translated into English, Korean, and Pashto. Lehr has analyzed an aspect of the grammar of proverb use.[17]

Balochi: For Balochi, a language spoken on both sides of the Pakistan-Afghan border, Badalkan gives a number of Balochi proverbs translated into English in his article, focusing on proverbs that are related to specific stories (2000). He also cites several published collections of Balochi proverbs, all published in Balochi. Six proverbs are given on the last pages (203, 204) of Dames' 1907 Popular poetry of the Baloches.[18]

Wakhi: Wakhi is spoken in Afghanistan, as well as in Pakistan and China. Almuth Degener compares some Wakhi proverbs with proverbs in other languages.[19] Buddruss, writing in German, described Wakhi proverbs from Hunza District in Pakistan.[20]

In addition to these publications in English, there are items about proverbs in languages spoken in Afghanistan published in other languages. These include:

Commonalities

Proverbs are often shared across languages when there is significant interaction among peoples. Some examples of shared proverbs among the languages of Afghanistan include:

- "Even on a mountain, there is still a road" found in Dari, Pashai, and Pashto.

- "The wound of the sword/gun will heal, but not that of the tongue" found in Dari, Pashai, and Pashto.

- "If you plan to keep elephants/camels, make your door high" found in Dari, Pashai, and Pashto

- "An intelligent enemy is better than a foolish friend" found in Dari, Pashai, and Pashto, but traceable to Al-Ghazali, a Persian poet of the 11th century.

- "With too many butchers, the cow dies without being ceremonially slaughtered corrected" found in Pashto,[21] Pashai,[22] Dari[23]

The proverbs of Afghanistan are not fixed, archaic expressions. For example, there is a traditional proverb in Pashto (Bartlotti and Khattak 2006: 264) and Dari (Wilson 2002:32), "The wound of the sword will heal, but not that of the tongue." The Pashai form of this proverb reflects a more modern form of weapon, "A bad wound by a gun will be cured, but the wound by a bad word won’t be cured" (Yun 2010:159). Another example of an updated proverb is today's Pashai proverb "An unloaded gun makes two people afraid" compared with a Pashto proverb published in 1876 reflecting an older form of military technology "Of the broken bow two persons are in fear" (1876:408).

Not surprisingly, proverbs in all four of the languages documented have proverbs that mention nouns common in Afghanistan, such as "camels", "mountains", and "poverty".

It is not surprising to find proverbs that reflect Afghanistan's Islamic traditions, such as

- "To repeat the Koran often is good" Pashto (Thorburn 1876:374)

- "It is the sword that protects Islam" Pashto (Barlotti & Khattak 2006:36)

- "Saying 'Salam' [an Islamic religious expression] is a sign of true faith" Dari (Wilson 2002: 51)

- "In childhood you are playful, in youth you are lustful, in old age you are feeble; So when will you before God be worshipful?" Dari (Wilson 2022:54)

- "You have cleansed your body, how will you cleanse your soul?" Pashto (Barlotti & Khattak 2006:48)

A common element among the proverb traditions of Afghanistan is that some proverbs are linked to stories (though this is not unique to Afghanistan). Proverbs that trace their origin to stories are found in Pashto (Thorburn 1876: 314), Dari (Zellem 2012b:153), and Balochi (Badalkhan 2000).

Analysis of Afghan proverbs

For most Afghan languages, the first challenge is to collect proverbs before analysis can be done. For Pashto, which has the oldest and largest collections of proverbs, there have been two dissertations that analyzed the links between their proverbs and culture. (Though both projects were done with Pashto speakers on the Pakistani side of the border, the findings are expected to apply on the Afghan side of the borders, as well.) The first was about '"Pashtunwali", "the way of the Pashtuns", ... a code of honor embracing the customary law, morality, ethos, and notion of the ancestral heritage associated with "being Pashtun" '.[24] The second dissertation 'argues that Pashtun proverbs encode and promote a patriarchal view and sexist ideology.'[25] Gender identities and roles as expressed in Pashto proverbs are also described in an article-length presentation.[26] Additionally, there is an article about the status of women as seen through Pakhtun proverbs.[27] Pashto proverbs have also been studied to show attitudes related to marriage.[28] Two Pashto speakers from Pakstan have studied gender and Pashoto proverbs.[29]

Kohistani has written a thesis to show how understanding Afghan Dari proverbs will help Europeans understand Afghan culture.[30]

The use of proverbs and other artistic language in talking about war and instability in Afghanistan is the subject of a study by Margaret Mills. [31]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Edward Zellem 2012b: i)

- ↑ Concise English Afghan Dari Dictionary & Proverbs, Behzad Book Center

- ↑ Wilson's 100 proverbs

- ↑ Edward Zellem. 2015. Zarbul Masalha. Tampa, FL: Cultures Direct.

- ↑ Lynch, Ruth. 2016. Review of Zarbul Masalha: 151 Afghan Dari Proverbs. Online access to review Archived 2017-08-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 2013 award by MWSA Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Noor Nazrabi. 2014. Afghanische Redensarten und Volksweisheiten, with illustrations by Moshtari Hillal. Hamburg: Afghanistik Verlag.

- ↑ Mataluna: 151 Afghan Pashto Proverbs. 2014. Tampa: Cultures Direct.

- ↑ Kulberg, Eve. 2015. Review of Mataluna: 151 Afghan Pashto Proverbs. Online access.

- ↑ Leonard Bartlotti. 2000. Negotiating Pakhto: Proverbs, Islam and the Construction of Identity among Pashtuns. University of Wales: Ph.D. thesis. Web access

- ↑ Shinwari, M. M. K. (1999). Da mataluno qisay (stories of proverbs). Peshawar: Master Printers, Mohalla Jangi.

- ↑ Lashkari, M. A. (2005). Oulasi mataluna (Popular Proverbs). Peshawar: Zeb Art Publishers

- ↑ Lashkari, M. A. (2009). Da mataluno qisay: Ter pa her baqi rozgar (Stories of proverbs: Old forgotten new adopted). Peshawar: Zeb Art Publishers.

- ↑ Boyle, Cecil Alexander. 1926. "Naqluna": Some Pushtu Proverbs and Sayings. Allababad: The Pioneer Press.

- ↑ Noor Sanauddin. 2016. Pashto Proverb Collections: A Critical Chronology. Pashto 45.651:57-72. Web access[usurped]

- ↑ Farid, Neelam, and Muhammad Ali Dinakhel. "EDUCATIONAL IMPACT OF THE GENDER RELATED PROVERBS ON THE LIFE OF PASHTUN WOMAN." PalArch's Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 20, no. 2 (2023): 20-30.

- ↑ p. 293. Lehr, Rachel. 2014. A descriptive grammar of Pashai: The language and speech of a community of Darrai Nur. Phd dissertation, University of Chicago.

- ↑ scanned copy of Popular poetry of the Baloches

- ↑ Degener, Almuth. "Family Relationshios in Proverbs from Northern Pakistan." Proverbium: Yearbook of International Proverb Scholarship 39, no. 1 (2022): 1-28.

- ↑ Buddruss, Georg. “Eine einheimische Sammlung von Wakhi-Sprichwörtern aus Hunza“. Central’naja Azija, Vostočnyj Gindukuš, edited by Vladimir Vasiljevič Kushev, Nina Leonidovna Luzhetskaja, Lutz Rzehak, and Ivan Michailovič Steblin-Kamenskij. Moskva: Akademija Nauk Rossii 1998, p. 30-45.

- ↑ p. 109, Tair & Edwards 2006

- ↑ p. 161. Yun 2010

- ↑ p. 37,38, Wilson

- ↑ p. iii. Leonard Bartlotti. 2000. Negotiating Pashto: Proverbs, Islam and the Construction of Identity among Pashtuns. University of Wales: Ph.D. thesis. Web access

- ↑ Sanauddin, Noor. (2015) Proverbs and patriarchy: analysis of linguistic sexism and gender relations among the Pashtuns of Pakistan. University of Glasgow: PhD thesis. PDF of the dissertation

- ↑ Khan, Qaisar, Nighat Sultana, Arab Naz. 2015. The Linguistic Representation of Gender Identities in Pakhtu Proverbs. NUML Journal of Critical Inquiry. 13 (2). Web access

- ↑ Ikram Badshah and Sarfraz Khan. 2017. "Understanding the Status of Women through the Deconstruction of Sexist Proverbs in Pakhtun Society in Pakistan." THE 6th INTERNATIONAL ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ON SOCIAL SCIENCES pp. 25-29.

- ↑ Badshah, Ikram and Sarfraz Khan. Understanding Pakhtun Society through Proverbs. Journal of Asian Civilizations Islamabad Vol. 38.2, (Dec 2015): 159-171.

- ↑ Farid, Neelam, and Muhammad Ali Dinakhel. "Economic Impact of the Gender Related Proverbs of Pashto on the Life of Woman: An Analysis in the Light of Foucault’s Concept of Power and Knowledge." PalArch's Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 20, no. 1 (2023): 185-195.

- ↑ Kohistani, Zahra. 2011. Understanding culture through proverbs. University of Amsterdam MA thesis. Online access

- ↑ Mills, Margaret A. "Gnomics: Proverbs, Aphorisms, Metaphors, Key Words and Epithets in Afghan Discourses of War and Instability." Afghanistan in Ink: Literature Between Diaspora and Nation (2013): 229-253.

References

- Badalkhan, Sabir. 2000. "Ropes break at the weakest point." Some examples of Balochi proverbs with background stories. Proverbium 17:43-70.

- Bartlotti, Leonard. 2000. Negotiating Pakhto: Proverbs, Islam and the Construction of Identity among Pashtuns. University of Wales doctoral thesis. Web access

- Bartlotti, Leonard and Raj Wali Shah Khattak, eds. 2006. Rohi Mataluna: Pashto Proverbs, (revised and expanded edition). First edition by Mohammad Nawaz Tair and Thomas C. Edwards, eds. Peshawar, Pakistan: Interlit and Pashto Academy, Peshawar University.

- Bell, Evan. 2009. An analysis of Tajik proverbs. MA thesis, Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics. Tajik proverb volume available.

- Benawa, ʻAbd al-Raʼūf. 1979. Pashto Proverbs Pax̌to matalūna, translated into English by A.M. Shinwari. Kabul: Government Printing Press.

- Boyle, Cecil Alexander. 1926. "Naqluna": Some Pushtu Proverbs and Sayings. Allababab: The Pioneer Press.

- Buddruss, Georg. 1992. Waigali-Sprichwörter. Studien zur Indologie und Iranistik. 16: 65–80.

- Dames, Longworth. 1907. Popular poetry of the Baloches. London: Royal Asiatic Society. Web version

- Dor, Rémy. 1982. 'Metel' ou l'appretissage du comportement. Le Proverbe chez les Kirghiz du Pamir afghan. Journal asiatique 270:67-146.

- Enevoldsen, Jens. 1967. (last re-printed 2004). Sound the bells, O moon, arise and shine! Peshawar: University Book Agency, Khyber Bazar and Interlit Foundation.

- Kreyenbroek, Philip G. 2010. Oral literature of Iranian languages / Kurdish, Pashto, Balochi, Ossetic, Persian and Tajik. Companion volume II to A history of Persian literature. London & New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Tair, Mohammed Nawaz and Thomas C. Edwards. 1982. Rohi Mataluna. Pashto Proverbs, 1st ed. Peshawar: Pashto Academy, University of Peshawar.

- Thorburn, S. S. 1876. Bannú; or Our Afghan frontier. London: Truebner and Co. Available online for free

- Wilson, J. Christy. 2002. One hundred Afghan Persian proverbs, 3rd ed., revised. Peshawar, Pakistan: Interlit. Online access

- Yun, Ju-Hong and Pashai Language Committee (Eastern Region Community Development Project of SERVE Afghanistan). 2010. On a mountain there is still a road. Peshawar, Pakistan: InterLit Foundation. ISBN 978-969-8343-44-6.

- Zellem, Edward. 2012a. Afghan Proverbs Illustrated'. ISBN 978-1-4792-8745-1.

- Zellem, Edward. 2012b. Zarbul Masalha: 151 Afghan Dari Proverbs. ISBN 1475093926.

- Zellem, Edward. 2013a. Afganskii Poslovitsi Illyoostrirovanniy. (Translated by Yasamin Rahmani and Asadullah Rahmani.) ISBN 978-1490968421.

- Zellem, Edward. 2013b. Afghanische Sprichwörter Illustriert. (Translated by Christa Ward.) ISBN 1480247456.

- Zellem, Edward. 2013c. Proverbes Illustrés Afghans. (Translated by Bertrand Voirin.) ISBN 978-1482099591.

- Zellem, Edward. Mataluna: 151 Afghan Pashto Proverbs, Hares Ahmadzai (Editor). Tampa, FL: Cultures Direct Press. ISBN 978-0692215180.

External links

- Dari proverb poster

- Pashto proverb poster

- Afghan Proverbs Website

- Pashto provebs with English translations

- Dari proverbs

- Links to books of Pashto and Dari proverbs in Arabic script -- Link to website

- Link to Balochi proverbs in Arabic script -- Link to website