| Pterodaustro Temporal range: Early Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of a fossil specimen at the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales in Caballito, Buenos Aires, Argentina | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Family: | †Ctenochasmatidae |

| Subfamily: | †Ctenochasmatinae |

| Tribe: | †Pterodaustrini |

| Genus: | †Pterodaustro Bonaparte, 1970 |

| Species: | †P. guinazui |

| Binomial name | |

| †Pterodaustro guinazui Bonaparte, 1970 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

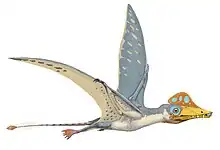

Pterodaustro is a genus of ctenochasmatid pterodactyloid pterosaur from South America. Its fossil remains dated back to the Early Cretaceous period, about 105 million years ago.

Discovery and naming

The first fossils, among them the holotype PVL 2571, a thigh bone, were discovered during the late 1960s by José Bonaparte in the Lagarcito Formation, situated in the San Luis Province of Argentina, and dating from the Albian. The genus has later also been found in Chile in the Santa Ana Formation. At the Argentine site, the just 50 square meters (540 sq ft) large "Loma del Pterodaustro", since then, during several expeditions, over 750 Pterodaustro specimens have been collected, 288 of them having been catalogued until 2008. This makes the species one of the best known pterosaurs, with examples from all growth stages, from egg to adult.

The genus was named in 1969 by José Bonaparte as an as yet undescribed nomen nudum. The first description followed in 1970, making the name valid, the type species being Pterodaustro guiñazui.[2] The generic name is derived from Greek pteron, "wing" and Latin auster, "south (wind)". The elements are combined as a condensed pteron de austro, "wing from the south". The specific name honors paleontologist Román Guiñazú. It was amended in 1978 by Peter Wellnhofer into guinazui, because diacritical signs such as the tilde are not allowed in specific names.

Description

Pterodaustro has a very elongated skull, up to 29 centimeters (11 in) long. The portion in front of the eye sockets comprises 85 percent of skull length. The long snout and lower jaws curve strongly upwards; the tangent at the point of the snout is perpendicular to that of the jaw joint. Pterodaustro has about a thousand bristle-like modified teeth in its lower jaws that might have been used to strain crustaceans, plankton, algae, and other small creatures from the water.[3] These teeth stand for the most part not in separate alveoli but in two long grooves parallel to the edges of the jaw. They have a length of 3 centimeters (0.098 ft) and are oval in cross-section, with a width of just 0.2 to 0.3 millimeters (0.0079 to 0.0118 in). At first it was suspected these structures were not true teeth at all, but later research established they were built like normal teeth, including enamel, dentine and a pulp. Despite being made of very hard material, they might still have been flexible to some extent due to their extreme length-width ratio, a bend of up to 45 degrees being possible.[4] The upper jaws also carried teeth, but these were very small with a flat conical base and a spatula-formed crown. These teeth also do not have separate tooth sockets but were apparently held by ligaments in a special tooth pad, that was also covered with small ossicles, or bone plates.

The back of the skull was also rather elongated and in a low position; there are some indications for a low parietal crest.

Pterodaustro had a maximum adult wingspan of approximately 3 m (9.8 ft) and a maximum body mass of approximately 9.2 kg (20 lb).[5] Its hindlimbs are rather robust and its feet large. Its tail is uniquely elongated for a pterodactyloid, containing twenty-two caudal vertebrae, whereas other members of this group have at most, sixteen.

Paleobiology

Pterodaustro probably strained food with its tooth comb, a method called "filter feeding", also practised by modern flamingos.[6] Once it caught its food, Pterodaustro probably mashed it with the small, globular teeth present in its upper jaw. Like other ctenochasmatoids, Pterodaustro has a long torso and proportionally massive and splayed hindfeet, adaptations for swimming.[7]

Robert Bakker suggested that, like flamingos, this pterosaur's diet may have resulted in a pink hue.[8]

At least two specimens of Pterodaustro have been found, MIC V263 and MIC V243, with gizzard stones in the stomach cavity, the first ever reported for any pterosaur. These clusters of small stones with angled edges support the idea that Pterodaustro ate mainly small, hard-shelled aquatic crustaceans using filter-feeding. Such invertebrates are abundant in the sediment of the fossil site.[9]

A study of the growth stages of Pterodaustro concluded that juveniles grew relatively fast in their first two years, attaining about half of the adult size. Then they reached sexual maturity, growing at a slower rate for four to five years until there was a determinate growth stop.[10]

In 2004 a Pterodaustro embryo in an egg was reported, specimen MHIN-UNSL-GEO-V246. The egg was elongated, 6 centimeters (2.4 in) long and 22 millimeters (0.87 in) across, and its mainly flexible shell was covered with a thin layer of calcite, 0.3 millimeters thick.[11] Three-dimensionally preserved eggs were reported in 2014.[12]

Comparisons between the scleral rings of Pterodaustro and modern birds and reptiles suggest that it may have been nocturnal and similar in activity patterns to modern anseriform birds that feed at night,[13] although method of this research is questioned by some researchers.[14]

Because of its long torso and neck and comparatively short legs, Pterodaustro was unique among pterosaurs in having difficulties to launch. Even with the pterosaurian quadrupedal launching mechanism, it would have required frantic and fairly-low angled take-offs possible only in open areas, much like modern geese and swans.[7]

Phylogeny

Bonaparte in 1970 assigned Pterodaustro to the Pterodactylidae; in 1971 to a Pterodaustriidae. However, from 1996 cladistic studies by Alexander Kellner and David Unwin have shown a position within the family Ctenochasmatidae, together with other filter feeders.[7]

In 2018, a topology by Longrich, Martill and Andres recovered Pterodaustro within the family Ctenochasmatidae, more precisely within the tribe called Pterodaustrini, in a more basal position than Beipiaopterus and Gegepterus.[15]

| Ctenochasmatidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ↑ L. Codorniú and Z. Gasparini. 2007. Pterosauria. In Z. Gasparini, L. Salgado, R. A. Coria (eds.), Patagonian Mesozoic Reptiles. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN 143-166.

- ↑ Bonaparte, J. F. (1970). "Pterodaustro guinazui gen. et sp. nov. Pterosaurio de la Formacion Lagarcito, Provincia de San Luis, Argentina y su significado en la geologia regional (Pterodactylidae)". Acta Geologica Lilloana. 10: 209–225.

- ↑ Wellnhofer, Peter (1996) [1991]. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pterosaurs. New York: Barnes and Noble Books. p. 132. ISBN 0-7607-0154-7.

- ↑ John D. Currey (1999). "The design of mineralised hard tissues for their mechanical functions". Journal of Experimental Biology. 202 (23): 3285–3294. doi:10.1242/jeb.202.23.3285. PMID 10562511.

- ↑ Naish, Darren; Witton, Mark P.; Martin-Silverstone, Elizabeth (22 July 2021). "Powered flight in hatchling pterosaurs: evidence from wing form and bone strength". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 13130. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1113130N. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-92499-z. PMC 8298463. PMID 34294737.

- ↑ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 104. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- 1 2 3 Witton, Mark P. (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691150613.

- ↑ Jinny Johnson (2000). Fantastic Facts About Dinosaurs. Parragon Book Service. ISBN 978-0-7525-3166-3.

- ↑ Codorniú, L., Chiappe, L.M., Arcucci, A., and Ortiz-Suarez, A. (2009). "First occurrence of gastroliths in Pterosauria (Early Cretaceous, Argentina)". XXIV Jornadas Argentinas de Paleontología de Vertebrados

- ↑ Chinsamy, A., Codorniú, L., and Chiappe, L. M. (2008). "Developmental growth patterns of the filter-feeder pterosaur, Pterodaustro guinazui". Biology Letters. 4 (3): 282–285. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0004. PMC 2610039. PMID 18308672.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Chiappe, L. M., Codorniú, L., Grellet-Tinner, G. and Rivarola, D. (2004). "Argentinian unhatched pterosaur fossil" (PDF). Nature. 432 (7017): 571–572. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..571C. doi:10.1038/432571a. PMID 15577899. S2CID 4396534.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Grellet-Tinner, G.; Thompson, M.; Fiorelli, L. E.; Argañaraz, E. S.; Codorniú, L.; Hechenleitner, E. M. N. (2014). "The first pterosaur 3-D egg: Implications for Pterodaustro guinazui nesting strategies, an Albian filter feeder pterosaur from central Argentina". Geoscience Frontiers. 5 (6): 759. doi:10.1016/j.gsf.2014.05.002. hdl:11336/6990.

- ↑ Schmitz, L.; Motani, R. (2011). "Nocturnality in dinosaurs inferred from scleral ring and orbit morphology". Science. 332 (6030): 705–708. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..705S. doi:10.1126/science.1200043. PMID 21493820. S2CID 33253407.

- ↑ Hall, Margaret I.; Kirk, E. Christopher; Kamilar, Jason M.; Carrano, Matthew T. (2011-12-23). "Comment on "Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology"". Science. 334 (6063): 1641–1641. doi:10.1126/science.1208442. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ↑ Longrich, N.R., Martill, D.M., and Andres, B. (2018). Late Maastrichtian pterosaurs from North Africa and mass extinction of Pterosauria at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary. PLoS Biology, 16(3): e2001663. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2001663