| Purple urine bag syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

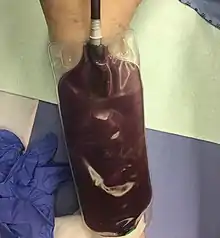

| Purple urine bag syndrome usually presents as urine with a purplish discoloration accumulating in a catheterized person's collection bag. |

Purple urine bag syndrome (PUBS) is a medical syndrome where purple discoloration of urine occurs in people with urinary catheters and co-existent urinary tract infection. Bacteria in the urine produce the enzyme indoxyl sulfatase. This converts indoxyl sulfate in the urine into the red and blue colored compounds indirubin and indigo.[1] The most commonly implicated bacteria are Providencia stuartii, Providencia rettgeri, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, Escherichia coli, Morganella morganii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[2]

Signs and symptoms

People with purple urine bag syndrome usually do not complain of any symptoms. Purple discoloration of urine bag is often the only finding, frequently noted by caregivers. It is usually considered a benign condition, although in the setting of recurrent or chronic urinary tract infection, it may be associated with drug-resistant bacteria.[3]

Pathophysiology

Tryptophan in the diet is metabolized by bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract to produce indole. Indole is absorbed into the blood by the intestine and passes to the liver. There, indole is converted to indoxyl sulfate, which is then excreted in the urine. In purple urine bag syndrome, bacteria that colonize the urinary catheter convert indoxyl sulfate to the colored compounds indirubin and indigo.[1]

Diagnosis

Purple urine bag syndrome is a clinical diagnosis, the cause of which may be investigated using a variety of laboratory tests or imaging.

Treatment

Antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin should be administered and the catheter should be changed. If constipation is present, this should also be treated.[4]

Epidemiology

Purple urine bag syndrome is more common in female nursing home residents. Other risk factors include alkaline urine, constipation, and polyvinyl chloride catheter use.[5]

History

The syndrome was first described by Barlow and Dickson in 1978.[6]

References

- 1 2 Tan, CK; Wu YP; Wu HY; Lai CC (August 2008). "Purple urine bag syndrome". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 179 (5): 491. doi:10.1503/cmaj.071604. PMC 2518199. PMID 18725621.

- ↑ Lin, CH; Huang HT; Chien CC; et al. (December 2008). "Purple urine bag syndrome in nursing homes: ten elderly case reports and a literature review". Clinical Interventions in Aging. 3 (4): 729–734. doi:10.2147/cia.s3534. PMC 2682405. PMID 19281065.

- ↑ Bhattarai, M; Mukhtar HB; Davis TW; et al. (2013). "Purple urine bag syndrome may not be benign: a case report and brief review of the literature". Case Reports in Infectious Diseases. 2013: 863853. doi:10.1155/2013/863853. PMC 3705812. PMID 23864970.

- ↑ Kalsi, DS; Ward, J; Lee, R; Handa, A (November 2017). "Purple urine bag syndrome: a rare spot diagnosis". Disease Markers. 2017: 9131872. doi:10.1155/2017/9131872. PMC 5727662. PMID 29317791.

- ↑ Su, FH; Chung SY; Chen MH; et al. (September 2005). "Case analysis of purple urine-bag syndrome at a long-term care service in a community hospital". Chang Gung Medical Journal. 28 (9): 636–642. PMID 16323555.

- ↑ Barlow, GB; Dickson JAS (March 1978). "Purple urine bags". Lancet. 1 (8062): 502. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90163-0. PMID 76045. S2CID 54340615.