| Pycnodysostosis | |

|---|---|

| |

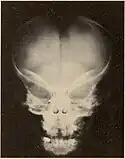

| Woman with pycnodysostosis | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, medical genetics, endocrinology |

Pycnodysostosis (from Greek: πυκνός (puknos) meaning "dense",[1] dys ("defective"), and ostosis ("condition of the bone")), is a lysosomal storage disease of the bone caused by a mutation in the gene that codes the enzyme cathepsin K.[2] It is also known as PKND and PYCD.[3]

History

The disease was first described by Maroteaux and Lamy in 1962[4][5] at which time it was defined by the following characteristics: dwarfism; osteopetrosis; partial agenesis of the terminal digits of the hands and feet; cranial anomalies, such as persistence of fontanelles and failure of closure of cranial sutures; frontal and occipital bossing; and hypoplasia of the angle of the mandible.[6] The defective gene responsible for the disease was discovered in 1996.[7] The French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) is believed to have had the disease.[8]

Signs and symptoms

Pycnodysostosis causes the bones to be abnormally dense; the last bones of the fingers (the distal phalanges) to be unusually short; and delays the normal closure of the connections (sutures) of the skull bones in infancy, so that the "soft spot" (fontanelle) on top of the head remains widely open.[9] Because of the bone denseness, those with the syndrome suffer from fractures.[7]

Those with the syndrome have brittle bones which easily break, especially in the legs and feet.

Other abnormalities involve the head and face, teeth, collar bones, skin, and nails. The front and back of the head are prominent. Within the open sutures of the skull, there may be many small bones (called wormian bones). The midface is less full than usual. The nose is prominent. The jaw can be small. The palate is narrow and grooved. There will be delay in fall of milk teeth. The permanent teeth can also be slow to appear. The permanent teeth are commonly irregular and teeth may be missing (hypodontia). The collar bones are often underdeveloped and malformed. The nails are flat, grooved, and dysplastic. High bone density, Acro-osteolysis and obtuse mandibular angle are the characteristic radiological findings of this disorder.[10]

Pycnodysostosis also causes problems that may become evident with time. Aside from the broken bones, the distal phalanges and the collar bone can undergo slow progressive deterioration. Vertebral defects may permit the spine to curve laterally resulting in scoliosis. The dental problems often require orthodontic care and cavities are common.

Patients with PYCD are at a high risk of severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) due to upper airway obstructions.[11] OSA must be managed to prevent long term pulmonary complications.[11]

Amongst infrequent complications, attention should be paid to maxillofacial anomalies. Snoring can be one of the presenting complaints and this needs early evaluation and management of obstructive sleep apnea if present to prevent long term pulmonary complications.

Genetics

PYCD is a rare autosomal recessive disorder.[12][13] The molecular basis of pycnodysostosis was elucidated in 1996 by Gelb and collaborators and the disorder results from biallelic pathogenic mutation in CTSK gene (OMIM * 601105). This gene codes for cathepsin K, a lysosomal cysteine protease that is highly expressed in osteoclasts and plays a significant role in bone remodelling by degenerating the bone matrix proteins such as type I collagen, osteopontin, and osteonectin. Defective function of cathepsin K therefore results in failure of normal degradation of the accumulated collagen fibres in the resorptive microenvironment by osteoclasts despite normal generation of ruffled membranes and mobilization of bone minerals.

If both parents of a diagnosed individual are heterozygous for a CTSK pathogenic variant, siblings of the individual have a 25% chance of being affected, a 50% chance of being an asymptomatic carrier, and a 25% chance of being unaffected and not a carrier.[14]

Diagnosis

Pycnodysostosis is one of those disorders which has a typical facial gestalt[15] and can be clinically identified in the majority of cases. Skeletal surveys can also aid in clinical diagnosis and characteristic features include high bone density, acro-osteolysis and obtuse mandibular angle. Molecular testing will be the final resort to confirm the diagnosis. Due to the limited number of exons of the CTSK gene that causes pycnodysostosis, a cheaper genetic testing called Sanger sequencing can be employed to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment and management

The treatment of pycnodysostosis is currently based on symptomatic management and no active trials are in place for a curative approach. The comorbidities like short stature, fracture and maxillofacial issues can be easily managed when identified earlier, which can improve the quality of life of these individuals.

Management can include physical, medical, and psychological care including:[16]

- Growth hormone therapy

- Environmental and/or occupational modifications

- Orthopedic care for fractures and scoliosis

- Sleep medicine to address sleep apnea

- Dental and orthodontic care

Patients are likely to have annual physical exams with doctors and specialists to monitor all symptoms.[16]

Epidemiology

Its incidence is estimated to be 1.7 per 1 million births.[4]

Differences from osteopetrosis

Many of the radiological findings of PYCD are similar to those of osteopetrosis, a disease that causes bone density due to a defect in bone reabsorption; however, the two diagnoses differ in several ways.[17][18] In PYCD, there is also:[18]

- Wormian bones

- Delayed closure of sutures and fontanels

- Obtuse mandibular angle

- Gracile clavicles that are hypoplastic at the lateral ends

- Partial absence of the hyoid bone

- Hypoplasia or aplasia of the distal phalanges and ribs

References

- ↑ "Dictionary of Botanical Epithets".

- ↑ Gelb, BD; Shi, GP; Chapman, HA; Desnick, RJ (1996). "Pycnodysostosis, a lysosomal storage disease caused by cathepsin K deficiency". Science. 273 (5279): 1236–1238. doi:10.1126/science.273.5279.1236. PMID 8703060. S2CID 7188076.

- ↑ "Pycnodysostosis". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2021-11-21.

- 1 2 Mujawar, Quais; Naganoor, Ravi; Patil, Harsha; Thobbi, Achyut Narayan; Ukkali, Sadashiva; Malagi, Naushad (December 2009). "Pycnodysostosis with unusual findings: a case report". Cases Journal. 2 (1): 6544. doi:10.4076/1757-1626-2-6544. ISSN 1757-1626. PMC 2740175. PMID 19829823.

- ↑ McKusick, Victor A. (1998-06-29). Mendelian Inheritance in Man: A Catalog of Human Genes and Genetic Disorders. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5742-3.

- ↑ Sedano, Heddie D. (July 1968). "Pycnodysostosis Clinical and Genetic Considerations". JAMA Network. 116 (1): 70–77. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1968.02100020072010. PMID 5657357.

- 1 2 Rodrigues, Cleomar; Gomes, Fernando-Antônio; Arruda, José-Alcides; Silva, Luciano; Álvares, Pâmella; da Fonte, Priscila; Sobral, Ana-Paula; Silveira, Marcia (2017-10-01). "Clinical and radiographic features of pycnodysostosis: A case report". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry. 9 (10): e1276–e1281. doi:10.4317/jced.54105. ISSN 1989-5488. PMC 5694160. PMID 29167721.

- ↑ Polymeropoulos, Mihael H.; Ortiz De Luna, Rosa Isela; Ide, Susan E.; Torres, Rosarelis; Rubenstein, Jeffrey; Francomano, Clair A. (June 1, 1995). "The gene for pycnodysostosis maps to human chromosome 1cen–q21". Nature Genetics. 10 (2): 238–239. doi:10.1038/ng0695-238. ISSN 1546-1718. PMID 7663522. S2CID 11723845.

- ↑ Motyckova, G; Fisher, DE (2002). "Pycnodysostosis: role and regulation of cathepsin K deficiency in osteoclast function and human disease". Current Molecular Medicine. 2 (5): 407–421. doi:10.2174/1566524023362401. PMID 12125807.

- ↑ Razmara, E; Azimi, H; Bitaraf, A; Daneshmand, MA; Galehdari, M; Dokhanchi, M; Esmaeilzadeh, E; Garshasbi, M (2020). "Whole‐exome sequencing identified a novel variant in an Iranian patient affected by pycnodysostosis". Molecular Genetics & Genomics Medicine. 3 (8): 1118. doi:10.1002/mgg3.1118. PMC 7057126. PMID 31944631.

- 1 2 Khirani, Sonia; Amaddeo, Alessandro; Baujat, Geneviève; Michot, Caroline; Couloigner, Vincent; Pinto, Graziella; Arnaud, Eric; Picard, Arnaud; Cormier-Daire, Valérie; Fauroux, Brigitte (2020). "Sleep-disordered breathing in children with pycnodysostosis". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 182 (1): 122–129. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.61393. ISSN 1552-4833. PMID 31680459. S2CID 207889726.

- ↑ Sayed Amr, Khalda; El-Bassyouni, Hala T.; Abdel Hady, Sawsan; Mostafa, Mostafa I.; Mehrez, Mennat I.; Coviello, Domenico; El-Kamah, Ghada Y. (October 2021). "Genetic and Molecular Evaluation: Reporting Three Novel Mutations and Creating Awareness of Pycnodysostosis Disease". Genes. 12 (10): 1552. doi:10.3390/genes12101552. PMC 8535549. PMID 34680947.

- ↑ Doherty, Mia Aa; Langdahl, Bente L.; Vogel, Ida; Haagerup, Annette (2021-02-01). "Clinical and genetic evaluation of Danish patients with pycnodysostosis". European Journal of Medical Genetics. 64 (2): 104135. doi:10.1016/j.ejmg.2021.104135. ISSN 1769-7212. PMID 33429075. S2CID 231587224.

- ↑ PMC, Europe. "Europe PMC". europepmc.org. Retrieved 2021-11-24.

- ↑ Sait H, Srivastava P, Gupta N, Kabra M, Kapoor S, Ranganath P et al. Phenotypic and genotypic spectrum of CTSK variants in a cohort of twenty-five Indian patients with Pycnodysostosis.Eur J Med Genet.2021;64:104235 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2021.104235.

- 1 2 PMC, Europe. "Europe PMC". europepmc.org. Retrieved 2021-11-30.

- ↑ "Osteopetrosis". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2021-12-04.

- 1 2 "Pycnodysostosis - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 2021-12-04.